The Fool in Atziluth, as we have already seen, was Ted, who in ‘Fulbright Scholars’ was wandering aimlessly, “where was it, in the Strand?”. The Strand, appropriately, is the site of an ancient riverside beach where boats were once literally stranded whilst their passengers continued their journeys into London on foot. There, ready for new adventures, Ted was distracted by a display of news photographs. He scanned the picture of newly arrived Fulbright scholars “wondering which of them [he] might meet” and noting “particularly the girls”. And his memory of all this was linked with his first taste of a fresh peach and the dawning, “dumbfound[ing]” knowledge of his own “ignorance of the simplest things”.

The Fool in Atziluth was also Sylvia, one of the scholars poised at the start of a new adventure in a new land.

So this was Aleph, October 1955, the start of it all. Both Ted and Sylvia, like Atziluthic archetypes, were young and fresh, open to new experiences and poised to begin their shared journey: their shared story. This poem, too, is Aleph. It is the “Once upon a time” of their story, and everything in it lives in the unreal light of memory and fable, and in the imagination of the poet and the reader. This was the Golden Age, the age of youth, freedom and innocence in which everything seemed possible.

The Fool in Briah, however, has already fallen from this protean state and is already in the process of creating a new self and a new life for that self. For Ted and Sylvia, this was a joint enterprise, as all their writing at this time showed. Traversing the twenty-two paths of the Atziluthic World, as the poems from ‘Fulbright Scholars’ (BL 3) to ‘55 Eltisley Avenue’ (BL 49) relate, they had met, fallen in love, married and moved into their first home in Cambridge. There, in November 1966, they entered a world of “rainbow darkness” in which “hand-in-hand” they would begin their new life together.

So begins the journey along the paths of Briah. In Briah’s watery, abstract world, where the conditions for creation are learned and the creative elements are assembled ready for use, The Fool steps onto the first path which moves from the Crown of the Cabbalistic Tree, Sephira 1 (Kether) towards Wisdom, Sephira 2 (Chokmah). On this, the Aleph path, the “Original Teacher’s Illumination” (Crowley) is invoked by the Cabbalistic quester and explored. The Birthday Letters poem, at this point, is ‘Chaucer’ (BL 51). And it is a wonderfully Fool-ish poem.

Sylvia, ecstatically inspired by “pure spirit”, perches precariously on a country stile and recites to a fool’s circle of “enthralled” (a very precise magician’s word) cows. These are her “imagined audience” – a jostling, awed, snorting ring of dumb (foolish) animals to whom she imparts the springtime evoked by her teacher, Chaucer, in The Canterbury Tales. She follows this with his description of “her favourite character in all literature” (SPLH April 8, 1957), the Wife of Bath, who is also a marvellously foolish creature in the ironic eyes of Chaucer’s narrator.

Ted, in this innocent and carefree scene, is so filled with the shared ecstasy and the springtime intoxication of it, that all other memories, then and as he recreated it in his poem, “had to go back into oblivion”. And this image of simultaneous fullness and emptiness is exactly the Fool’s Tarot number, zero, which contains both everything and nothing.

Ted too, reaches in this poem for illumination from one of his original teachers. Chaucer, who in the earlier poem ‘St. Botolph’s’ (BL 14) is “our Chaucer”, honoured by both Ted and Sylvia, here provides Ted with the words with which to begin a magical recreation of the “champagne ecstasy” of an April day. This is a time at which he and Sylvia are stepping out, like Chaucer’s pilgrims, along new paths and this is the poem in which Ted begins to imaginatively re-create this next stage of the Cabbalistic journey.

On the paths of the Briatic World, Ted and Sylvia experiment and test themselves, and learn from their varied experiences. In reality, this time extended from November 1956 to February 1960. Sylvia completed her studies at Cambridge and they then moved to America. There they taught at respected academic establishments but found that teaching hindered rather than helped their creative lives. So, they saved their money and gave up their safe jobs in order to write. In Boston for a year they sampled the literary life, and Sylvia sought professional help from a psychologist for her depressions, her writing block and her panics. But America, it seems, depressed Ted (SPJ 26 Dec. 1958) and at this time they began to plan their move to England (SPJ 28 Jan. 1959). First, they travelled around America and Canada, testing one of many “thresholds” (‘Fishing Bridge' BL 87), “looking for you”, as Ted says of Sylvia in ‘The Badlands’ (BL 82). To no avail. So, after a brief spell at the artists’ colony of Yaddo and with all their plans (the Yetziritic patterns which now existed in their minds) now ready to be implemented, they moved to England.

In the Yetziritic World, the possibility of creation which the quester has gained by traversing the paths of Atziluth and Briah is converted into something which has shape, as a pattern has shape, but which is not yet solid and tangible. For the poet, this intangible pattern is a certainty of what poetry is, what is does and how to go about creating it. It is the store of knowledge from which the poet writes and which comprises all the tools of a poet’s art. But it is not yet a fixed, consistent, manifest ‘voice’ crystallised in individual poems. On the Yetziritic pathways, questers begin to bring about their goals - to make them solid and tangible.

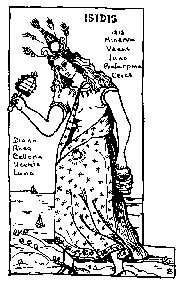

In Birthday Letters, the poem which represents The Fool in the World of Yetzirah is ‘Isis’ (BL 111). At first reading it seems an unlikely ‘Fool’ poem but there are elements of it which fit the pattern exactly. Above all, it is about birth and new beginnings. Ted emphasises this in the first line by recalling an earlier morning of freedom and anticipation in their lives, and he uses ‘America’ realistically and (as he constantly does in Birthday Letters) as a symbol of hope – a Promised Land.

Ted and Sylvia, now, are in England beginning their creative lives again as poets and, in this poem, as parents. Once again, certain “baggage” has been put behind them. Sylvia, in her Boston sessions with psychologist, Ruth Beuscher, has confronted her demons and “dealt with Death”. And her visit to her father’s grave in Winthrop (SPJ 9 March and 23 April 1959) at that time allowed her to “come to an agreement finally” with “my own father – the buried male-muse & god-creator” (SPJ 11 May 1958) and with her desires and fears about pregnancy (SPJ 13 Dec. 1958 and 13 June 1959).

Yet as the tarot Fool carries his baggage slung on a stick over his shoulder as he steps blithely forward, the “baggage” of past experience is never completely left behind. Sylvia has lightened her heaviest, psychological, baggage (which became Ted’s burden, too, when they married) but it seems to him, as he writes this poem, that “Death” may still have been with them “hidden”, “waiting for your habits / To come back and remember him”. What certainly was with them, like their “lightest bit of luggage” on the journey, was their unborn child. But the subject of this phrase, as it is positioned in the poem, is ambiguous, for the poem begins with the name of Isis, and she, too, “started with [them]” as part of their mental “luggage”.

Now, in

this poem, Ted invokes her as Black Isis, the poetic ‘teacher'

and goddess whose image Ted and Sylvia had hung on the wall of

their London flat for inspiration (SPLH 7 Feb. 1960), and

through her he challenges Death with Life.

Now, in

this poem, Ted invokes her as Black Isis, the poetic ‘teacher'

and goddess whose image Ted and Sylvia had hung on the wall of

their London flat for inspiration (SPLH 7 Feb. 1960), and

through her he challenges Death with Life.

In reality, Sylvia’s midwife was a small Indian woman (SPLH 1 April 1960), the “fairy godmother” Ted describes in the poem ‘Remission’ (BL 109). Now, in this next poem in the sequence, she becomes a priestess of Black Isis and Ted uses her to magically summon the Goddess, ritually invoking Isis by her full magical name, Polymorphous Daemon Magnae Deorum Matris, and welcoming her into the poem with the music of voice and sistrum. This is powerful and dangerous magic which usually only an adept will attempt, and he takes care to contain her powers within the poem, giving her a body “to create with” and the “soft mask” of a human face which, with vivid realism, is both “triumphant” and “grotesque” on “the bed of birth”.

Sylvia, herself, at this moment of birth in the poem, becomes Isis: embodying the Goddess, the Enchantress, Great Mother, bloody and fecund vehicle of life. The poem brims with her exhilaration and exultance, just as the birth really did fill Sylvia with these energies (SPLH Note: 1 April 1960). And Life is triumphant. A mother, a newborn child and a father (here present as the poet), the three essential elements for continuous regeneration, are here, as they were then, ecstatically linked in the promise which new life brings.

By giving birth, Sylvia’s triumph over Death was something quite apart from her battle against the depressions caused by her father’s death and her own struggles against writing blocks and “poetic death”. It was a different kind of triumph, expressing a different aspect of the Goddesses powers. But summoned into the poem by Ted, Isis as Enchantress also provides poetic inspiration to support his magic and this poem brings Sylvia vividly to life.

Sadly, the promise and the new optimism with which Ted and Sylvia here began their journey along the Yetziritic paths was not to last. Death had been only temporarily defeated and, although Sylvia “had hidden him / From [herself] and deceived even Life”, she had not conquered him. So, by the time Ted and Sylvia reach the lower, material World of Assiah, their difficulties have still not been resolved and they are unprepared for challenges which face them. Although their individual determination to achieve direct access to the sources of their creative inspiration and to live their lives as poets has not diminished, their paths have begun to diverge. Isis, too, whilst still their teacher and inspiration, takes on a far more dangerous aspect in this lower World, for her power is most often present here in the form of Hecate, Kali, Lilith and other dark goddesses of the Underworld which is so close below the World of Assiah.

‘Dreamers’ (BL 157), which is the poem which represents the path of The Fool in the World of Assiah, describes events which began in August 1961, and it marks a less happy beginning. Choices already made and experience gathered along the paths already travelled, have brought the questers to this next path with patterns of thought and behaviour ready to be crystalized. And because Assiah is the world of crystalization, a place of fixed, earth-bound, material things, and closer to the Underworld than to the Divine Source, it is a world of masks and hollow values in which the journey is less free. Fate holds stronger sway. And the Fool displays more characteristics of the Trickster - is more reckless and more subject to the instinctive, earthy, animal energies. He still carries his staff, or wand, over his shoulder and still has magical, psychic powers, but he is less able to change things. He is altogether more worldly-foolish - more full of folly.

All three people in ‘Dreamers’ are foolish and naïve, fascinated and “helpless” as if in an opiate dream. It is not that they have no freedom, but that they are beginning this journey in a weak, vulnerable, emotional state, too easily swayed by their desires, too ready to be made the “puppets” of Fate. It is this weakness, which allows Fate to sniff them out and “assemble” them for “its experiment”.

Assia Wevill is the third helpless dreamer in this poem. In September, 1961, she and her husband had taken over the London flat in which Sylvia and Ted had been living before they bought Court Green. Sylvia and Ted had been so drawn to them that they had destroyed a cheque from another man in order to let them have the flat (SPLH 13 Aug. 1961), and in May, 1962, Sylvia invited this “nice young Canadian poet and his very attractive, intelligent wife” down to Devon for the weekend (SPLH 14 May 1962).

Assia Guttmann, whose mother was German and father a Russian Jew, had been born in Berlin in 1927 and had lived in the German Colony in Palestine during the war. She spoke Russian, German and English, and a little Hebrew “survived on bats and spiders / In the guerilla priest-hole / Under [her] tongue” (‘Shibboleth’, Capriccio, Gehenna, 1990). Sylvia was “fascinated” by her accent and her history and her erotic, exotic “many blooded beauty”. It was almost as if she were Sylvia’s “dream-self": the shadowy double who crept into the nightmare fantasies of poems like ‘Lady Lazarus’ (SPCP 244).

Sylvia, in ‘Dreamers’, “cultivated her”, but was wary of this “Lilith of abortions” who touched her children with “tiger-painted nails”. This is a chilling image, for Lilith, in Jewish legend, was the first wife of Adam who, banished and demonised, was jealous of Eve’s children and became their devourer. Lilith was made with Adam from dust and was his equal in every way but, refusing to submit to his will, she invoked the Name of God in order to escape. For this invocation, she was banished. Then, because Adam had no mate, God took one of Adam’s ribs and created Eve – made from him and therefore part of him and subject to his will. Lilith, meanwhile, conceived her own demonic children by coupling with men in their sleep, provoking erotic nightmares and nocturnal emission.

Yet there is another aspect to Lilith which the Cabbalists accept. She, who was created alongside Adam and from the same substance, is part of our humanity. It is we who, by rejecting her and demonising her, have made her dangerous and destructive. Cabbalists believe that we must learn to recognise, accept and value this rejected part of our nature, and that only in this way can her energies be used for creative, rather than destructive, purposes. Lilith, who to the early Jews represented unbridled sexual and emotional energies, becomes most dangerous when repressed or unacknowledged. Like the Cabbalists, most modern psychologists would also accept this view.

So, it is entirely appropriate that Ted, at the start of this fourth, most worldly journey along the Cabbalistic paths, should bring Lilith immediately into the light, revealing her and her witchy power and beauty within the controlled framework of this poem. It is entirely appropriate, too, that he should embody her in Assia Wevill, the woman whose dream world, as it seems from this poem, curiously matched his own, and who, in the Capriccio poems is described as matching his needs and desires then, as he matched hers:

So they ransacked each other. What he wanted

Was the gold, black-lettered pelt

Of the leopard Ein-Gedi.

She wanted only the runaway slave.

…

(‘Folktale’)

In ‘Dreamers’, Ted assembles the three people who were present at the start of this final journey along the Cabbalistic paths. They are three vulnerable people, brought together not entirely by accident, possibly by Fate, stepping off blindly and Fool-ishly towards the future. For the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, the epigram for meditation on this path is, appropriately, “Folly’s doom is ruin”.

Poetry and Magic text and illustrations. © Ann Skea 2000. For permission to quote any part of this document contact Dr Ann Skea at ann@skea.com