For the Cabbalist, the number 1 is unity, the beginning of all, the spark from the Divine Source which holds all in latency. It is all and nothing, the point and the circle. The number 2 represents the first division of that unity, the first extension of it into time and space. 2 is duality and polarity. It is the beginning and the end, spirit immersed in matter, light and dark, self and other. It can be symbolized by a cross with equal arms or by a bisected circle: unity divided but not separated.

That such polarities should derive from a single divine source is a problem which has long exercised theologians and philosophers but which poets and mythographers have resolved by allegory.

As Robert Fludd, the seventeenth-century Rosicrucian and Hermeticist whose Memory Theatre Hughes links with the Cabbalistic Tree of Life (SGCB 32), noted in his careful examination of Cabbala:

It is a wondrous thing, and passing all human understanding, that out of one Unity in essence and nature, two branches of such opposite nature should arise and sprout forth, as are Darkness (which is the seat of error, deformity, contention, privation, or death) and Light (which is the vehicle of truth, beauty, love, position, and life).

He noted, too, that faced with so “ticklish and difficult” a problem, “the wiser sort of Poetical Philosophers… did roll up or wrap” their explanations of this dichotomy in fabulous allegorical stories. Citing various Ancient Greek sources, he wrote:

… Orpheus, Hesiod, Euripides and Aeschylos1(who have enveloped in their fabulous Counts and Stories such hidden secrets as they had learned from divine persons, and such as were profoundly seen in the mysteries of God)… term [the one eternal essence] by the name Apollo in the day-time… Again they entitle it Dioysius in the night-time. (Fludd, Philosophia mosaical, Rammazenius, Gouda, 1638).

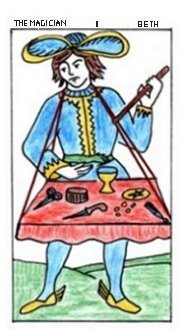

The number 2, then, is closely linked with Apollo and Dionysus, and with all the mythological and folk-lore figures which are related to them or derive from them. Of these, Hermes/Mercury is the most significant here because it is his image which appears as The Magician on the Tarot card associated with Beth, path 2 on the Cabbalistic journey.

Hermes, like his brothers Apollo and Dionysus, was fathered by the god, Zeus. Each had a different mother but all three mothers were of earthly origin, so their sons were born of the mating of heavenly and earthly elements. All three brothers, therefore, embodied duality. But, whereas Apollo and Dionysus represented the extremes of light and darkness, Hermes’ nature was a complex mixture of the two. He could understand and juggle the dualities of his nature and he was, therefore, chosen as a suitable guide and mediator for those travelling the Cabbalistic path numbered 2.

Hermes is generally described as clever and dexterous, skilful and devious, a guide to the human soul, a magician, a protector of travellers and, sometimes, a thief. According to Robert Graves, who tells the myth of Hermes birth and precociousness in detail (Greek Myths, Cassell, 1981. p.24), Zeus was amused and proud of his son’s cleverness and of his ability to trick his older brothers and to wriggle out of difficult situations, so he made him his herald and gave him responsibility for all divine property, including the human soul. Hermes promised Zeus that he would never tell lies, but that he could not promise always to tell the whole truth. Such, was his duplicity.

As befits Hermes’s complex and tricky nature, his Tarot card, which is usually called The Magician, may also be called The Magus (the knowledgable wielder of occult powers) or The Juggler (the devious magician who deceives by trickery and slight-of-hand).

The journeyer on path number 2 (Beth, the path of The Magician) must learn to recognise the duality of their own nature - their own potential for being Magus or Juggler – and the fact that all dualities are part of the same divine whole and must be reconciled if wholeness is to be regained. This is a tricky path. Hermes may offer guidance in some form, some sign perhaps from the gods, but the journeyer must be wary and alert to recognise it; and often the journeyer is faced with a choice, as at a crossroads, which ultimately determines his or her future direction.

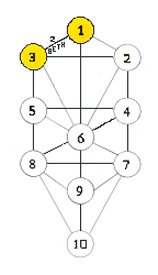

On the Cabbalistic Tree, the number 2 applies both to Sephira 2 (Chokmah) and to the path which joins Sephira 1 (Kether) and Sephira 3 (Binah). In Birthday Letters, the poem representing the number 2 is ‘Caryatids (2)’ (BL 5). This is not the second poem in the book but the one which, as discussed earlier, is positioned as if at the apex of the right-hand pillar of the temple. In the Atziluthic World, the world of archetypes, it represents Abba, the Father, the archetype of masculine energy; it also represents Hermes/Mercury (Mercury is the Roman name for this god), the embodiment of dualities. In the Atziluthic World, too, the first three paths, like the first three Sephiroth, share the divine energies and are considered equally necessary. They represent different aspects of the divine in matter which together make the whole: allegorically, they represent the Garden before the Fall – the garden in which Adam and Eve were created, in which the Serpent, too, existed, and in which Adam and Eve first became self-conscious.

In ‘Caryatids (2)’, Ted and his male Cambridge University friends still display many attributes of The Fool. They share the Fool’s naïve optimism; they are still “stupid with confidence”, “still growing”, “careless”: ready, we might say, for a fall. They wear the “playclothes” of The Magician and juggle their options, trying out various roles, “playing at friendship”, “playing at students”, improvising and acting on every mercurial whim with no thought for the consequences.

In February, 1956, Sylvia, also at Cambridge University, wrote in her journal about one young man she knew there:

… his ego is like an unbroken puppy… He flies socially, from girl to girl and party to party and tea to tea (25 Feb. 1956).

This is the pattern of behaviour of the men in the poem and it is, in its exaggeration, the archetype of male student behaviour. One of the polarities in the poem is the contrast between the “frivolous”, drunken world of these students and that of the world outside the university – the world which, like the “tourists” themselves, intrudes only briefly and “politely” on Sundays.

Yet this is not the main polarity in the poem, for although the visitors and the outside world are more sober and responsible than the students, a tourist’s world is in some ways equally artificial.

The main polarity is suggested by the crossroads at the heart of the poem and by the choice which Ted and all his friends must make. Realistically for students studying at university, there appear to be more than two choices. In the poem, the pattern is web-like, with roads which seem to lead to “every degree of the compass” and to open “too deeply”. Faced with such depths, it might seem from the students’ behaviour that they fearfully postpone any decision, preferring to live a superficial life, experimenting and testing their powers and able to rationalise this as gaining their “education” first.

But is buried fear of making such choices the only reason for the boredom and the “cornucopia of airy emptiness” which the students drunkenly drain and fill and drain again? And are these phrases, so closely linked in the poem with “the brown and the yellow ale” of one of James Joyce’s collection of drinking songs2, simply a sly description of university literary studies? Both, perhaps: just as the God-like “makings and unmakings” can equally well refer to these students’ poetic enterprises as to their games.

Yet

although such duality may be as intentional as it is appropriate,

it is not the only duality to be found. A far more revealing and

far more important duality, that between truth and illusion, is

suggested by Sylvia’s poem, which is an essential part of her and

is also the first female presence in the poem. At the centre of a

web, like the Indian goddess, Shakti-Mãyã who is

often represented as a spider, a seductress who weaves the web of

illusion which is our world of time and space, the poem sits at

the centre of the events which this poem describes and, almost

literally, “here at the centre” of this poem’s web of words.

Yet

although such duality may be as intentional as it is appropriate,

it is not the only duality to be found. A far more revealing and

far more important duality, that between truth and illusion, is

suggested by Sylvia’s poem, which is an essential part of her and

is also the first female presence in the poem. At the centre of a

web, like the Indian goddess, Shakti-Mãyã who is

often represented as a spider, a seductress who weaves the web of

illusion which is our world of time and space, the poem sits at

the centre of the events which this poem describes and, almost

literally, “here at the centre” of this poem’s web of words.

For the Cabbalist, the real world is not the impermanent, changing world in which we live, but the eternal, unchanging World of the Divine Spirit to which every soul must eventually return. The students in this poem live under the illusion that they have “time in plenty”; that “grave life” (the pun precisely suggests life after death) and the real World (capitalised at the beginning of a line) can be “deferred”. And, although the poem tells of events which did happen to a particular group of students, there is a sense in which we are all like these students when it comes to dealing with the world of spirit: we are all adept at immersing ourselves in the trivia of our lives and blocking out any deep thought about what happens after death.

Like these students, we are “like prisoners” of the illusory, impermanent reality of the material world, and the world of the spirit intrudes on our consciousness only, perhaps, on Sunday. Sunday is still, for most of us, a day off work when we can be tourists. Once, it was a Holy Day set aside for worshipping God. And it was named for the Sun god.

So, at the heart of this poem sits the spider which Campbell, in The Masks of God (Penguin, London, 1978. Vol IV p.78), identifies with “Duality (dvandva)” and also (p.291) with the great Goddess Mother of the universe in whose womb opposites are united. It is worth noting, too, that the Goddess is also Isis and, in the Tarot, the High Priestess, whose veil hides the Divine World from the profane3. As discussed earlier, Sylvia, in Caryatids (1) represents this goddess, so it is likely to be no accident that in Caryatids (2) we hear of the seductive “dance” of her “blonde veils”.

Into the world of mercurial masculine energies, the Goddess intruded. Sylvia’s poem, like Mãyã in her web, enticed the unwary and Ted and his friends were most unwary. Wiser men would have acknowledged the Goddess, accepted this female essence and begun to merge self and other. Ted and his friends made the opposite choice and there were no half measures about it, they jokingly dismembered her4. It was an act of hubris which affected all their lives and which led, in life and in the poem, to “an elegy” and to Sylvia’s bleak end.

Interestingly, although Ted and all his friends are depicted in the poem as fools, jugglers and tricksters, it is “our Welshman” (Daniel Huws) who is finally gifted with the second sight of a Bardic Magician. His elegy5 fills him “Worlds later” on Cader Idris, the magic mountain in Merionethshire, Wales, where it is said that anyone spending the night in “Merlin’s Chair” on the summit will be found in the morning mad, dead or a poet. So, this poem encompasses the juggler and the magician; the beginning and the end of Ted’s and Sylvia’s shared story; and the two worlds which are the whole concern of the Cabbalistic journey.

In Briah, the World where the abstract, intangible patterns of creation are formed, the poem on path 2, The Magician’s path, is ‘Ouija’ (BL 53). Suitably, it shows Ted and Sylvia seeking occult guidance by means of the alphabet, and duality is clearly defined from the start: “Two goals: ‘Yes’ at one end. ‘No’ at the other”.

Hermes, The Magician, it should be remembered is both a messenger (Zeus’s herald) and a guide to the human soul. He is also a juggler, expert at deception and jokes, and he is not always completely truthful. In ‘Ouija’ it seems that the spirits which communicate with Ted and Sylvia display all of these characteristics.

The first spirit contact, unwarily and swiftly made, seems to come from the Underworld rather than from the Divine Source. Her messages are full of images of death – of “rottenness”, “worms” and “bones” – and her influence is malign. She leaves them feeling unclean, as if “Some occult pickpocket / Had slit the soul’s silk and fingered us”.

Ted and Sylvia are disturbed by this, but not disturbed enough to stop their casual dabbling in the occult arts. Still naïve and overconfident of their psychic skills, they ignore the warning which the appearance of such a polluting spirit should have been to them and continue to lean precariously “over the brink of letters” and fish in the dark “well of Ouija”. The second time, they are answered by a swift joker and gambler who identifies himself, as Sylvia’s journals and a letter to her mother tell us, as ‘Pan’ (SPJ 4 July 1958; SPLH 5 July 1958).

In Ted Hughes’s editorial notes for Sylvia’s own poem, ‘Ouija’ (SPCP 77) and her verse ‘Dialogue Over a Ouija Board’ (SPCP 276-87), he writes of only one spirit which is the one they “regularly applied to”. It is this spirit’s communications which are described as usually being “gloomy” and “macabre”, and Sylvia’s own poem describes him as “a chilly god”, “a god of shades”. Her verse dialogue, the notes tell us, contains “the ‘spirit’ text of one of [their] Ouija sessions”. This male spirit, then, was Pan. And the couple in the verse dialogue note his playfulness and teasing, his “binge of jeers”, his “insolence”, and the realisation that “There is no truth in him”.

Pan, in Greek mythology, is most often identified as the son of Hermes. He is a temperamental and lazy soothsayer; he is guardian of the land’s bounty – sheep, cattle and bees; and he is the ugly, priapic, goat-footed god of Arcadia who is to be seen dancing and playing his reed pipes amongst the nymphs and satyrs who accompany the drunken Bacchus/Dionysus in his revels.

In Ted’s Birthday Letters poem, the Ouija spirit offers to prove his soothsaying skills by predicting the results of the week’s football matches so that Ted and Sylvia can “make their fortune” from the Littlewood’s Football Pools. But he is “too eager”: too focussed on the dichotomy of “winners and losers”, too involved in the games, too distracted by the multiplicity of details to choose correctly. He loses “Simple solidarity with the truth”.

“There’s a lesson here”, Ted notes. It is a clear and unequivocal statement, and it does point to an important lesson which was discussed in detail in Shakespeare and the Goddess of Complete Being (Faber, 1992). There, Ted writes of “Simplicity as the breath of the locked-up word of Divine Truth” (SGCB 278), the revelation of which is “first-hand and mystic”, not something which can be passed on in words or in ideologies; or, in the context of this poem, by the “discredited clairvoyance” of spirits summoned to tell fortunes.

Simplicity, too, is the essence of the poem which the Ouija spirit spells out and declares to be “a great poem”. The poem is like a Grail text, with its god hidden and nameless and its “myriad” weeping women whose tears water a parched wasteland, but it is also very like a Taoist poem about Simplicity and wordlessness. As Lao Tzu puts it in the ancient Chinese classic, Tao Te Ching (Penguin, 1963 p.57):

The Tao (Way) that can be spoken of

Is not the constant way;

The name that can be named

Is not the constant name.

The name that can be named is not the eternal name

The nameless was the beginning of Heaven and Earth,

The named was the Mother of the myriad6 creatures.

Simplicity and multiplicity; speech and wordlessness, nothing and everything: the division of the one into the many begins on this particular Cabbalistic path – path 2 – and the Taoist Way and the Cabbalistic journey both seek the same end: wholeness, the Nothing, the Divine Source.

But as well as a sacred element, there is an earthy, pagan side to this “great” poem, too. If the spirit is indeed Pan, he may well be recalling the part he once played in the orgiastic festivals of Dionysus. In these festivals, which were associated with the Goddess and with the death and resurrection of her son on whom the vegetative life of the earth depended, the priapic Pan was an important part of the retinue of the god who died (or was sacrificed), who was mourned by women in a frenzy of weeping, and who was reborn amidst joyous celebration by his followers, the Bacchants, as the mystic Iacchus.

The Ouija spirit also loves Shakespeare. His favourite play, King Lear, is one which Hughes considers in great detail in Shakespeare and the Goddess of Complete Being, where he describes it as a vital part of the “Mythic Equation” which he traces throughout Shakespeare’s work. He analyses it in terms of a journey of the soul in which words, silence, simplicity and truth, play an important part both in the story and as symbols which Shakespeare uses in essentially the same way as do many mystical teachings, including Cabbala.

But in Birthday Letters, the Ouija spirit’s love of Shakespeare again has a more mundane side to it. Lear’s line, “Never, never, never, never, never”, may be the most powerful and moving iambic line in the whole of Shakespeare, but Pan’s faulty memory of what follows it seems to offer some practical proof that Ted and Sylvia (who do remember what follows) are not controlling him. And his own facility with iambic metre (noted by Sylvia in her ‘Ouija’ poem as “apt iambics”) is a reminder that his daughter, Iambe, is credited with inventing this metre.

Fickle, rude, fallible and mischievous as the Ouija spirit clearly is, he is, Ted tells us, “More often serious”. Sylvia’s shocked, excessive and seemingly inexplicable reaction to Ted’s question about fame is linked directly in the poem’s lines with this statement. The Ouija glass does not move, it does not speak through the alphabet as it usually does, instead, it seems to the poet looking back, that Sylvia had from it some direct and silent revelation about their future and the terrible price that fame, when it came, would extract. It is a trick of Pan’s to cause sudden frights (hence the word ‘panic’) and this is exactly what Sylvia’s reaction seems to be. So this Ouija spirit expresses his nature, but also in his skills he demonstrates another duality: through him come both the casual dissemination of faulty prophecy and the direct intimation of some terrifying truth. He, like his father Hermes, does not always tell the whole truth, but he does not lie.

Sylvia, then, is frightened out of casually dabbling with the Ouija for purposes of fame and fortune. It seems that she learns a sharp lesson consistent with what the journeyer should learn from the energies of this path, which leads to Sephira 3 (Binah) Understanding. What she learns is consistent, too, with experience of the negative aspects of Binah, which include the vice, avarice; and with the Spiritual Experience of Binah, which is the Vision of Sorrow – a revelation of the illusionary materialistic World which may well be glimpsed here by the traveller.

Ted, too, learns from Sylvia’s instinctive response and her sudden words. She speaks as if possessed, her face distorted, her voice cracked, “like thunder and flash together”, and he learns that worldly ambition (the word is used three times in three lines) is not what he is meant to be seeking. He learns that he has misunderstood, that he has been under an illusion, and that he has changed his own life and his own natural inclinations for something which he thought others wanted of him but which turns out to have been a lie.

The poem began with the statement that the Ouija board always brought bad news. It ends with lines which tell the bald and awful truth of what just that one piece of intuitively received bad news really did portend for Sylvia. And so this poem encompasses the dualities of The Magician’s path and tells of some of the difficulties and dangers which must be faced on the Cabbalistic journey.

In the World of Yetzirah, where The Magician’s poem is ‘Epiphany’ (BL 113), Hermes/Mercury appears with his message at the very heart of the poem. The mood for this epiphany, this “meeting with a superhuman being” (as the COED defines this word) is set by the “lilac softness” of the April evening and by Ted’s almost “light headed” state. This is exactly the right dream-like mood for a spirit meeting.

On a bridge, more specifically on the very “hump” of the bridge, as if between two worlds (or two lives, as the poem later suggests) Ted meets a man who could almost be his shadow self: a man carrying a fox cub. Not only is a fox cub a suitably mercurial animal with the “flashing temperament” and “mannerless energy” of Hermes, it is also a creature which had special meaning for Ted. He used it often in his poetry and prose as if it was a familiar, a shamanic guide, almost his totem animal. Once before, in Cambridge, a spirit fox had visited him and that time he accepted its message and changed his life accordingly7.

In What is the Truth (Faber 1984) the fox appears more often than any other animal. It is a “jolly farmer” caring, as Pan does, for nature’s bounty – the hares, geese, voles, lambs and other small animals which just happen also to be its food. In another poem it is described in a riddle: an opera-scarfed dandy conducting his orchestra in the hen house, Robin Hood cheating King Pheasant of his gold and Dracula showing us the moon through the bottom of his top hat then bringing out of it: “in a flourish of feathers / The goose we locked up at sunset”. Yet another aspect of the truth about foxes in this book is its role as a scapegoat, pursued by the Hunting Horn for our “malice and suspicion”, our “wicked blood”, our fears and cowardice. And finally, in the beautiful and moving poem which first appeared as A Solstice in a limited edition (Sceptre Press 1978), it meets the hunters face to face:

A strangely dark fox

Motionless in its robes of office

Is watching us. It is a shock.

Too deep in the magic wood, suddenly

We have met the magician.

So, in ‘Epiphany’, it is not just a fox which Ted rejects on the hump of the bridge, but a creature which he regards as very special: Pan, Hermes, the juggler, the Magician, his own familiar.

The reasons for his choice, in the poem, are rational and mundane. Rather than pay the price of accepting the irrational, “boundless”, unpredictable energies of the fox, he chose the easy path: order, and the conventional and seemingly predictable domestic “crate of space”. It seems a sensible enough choice for a young man with a wife and a new-born baby, living in a tiny flat in London, to have made but looking back Ted sees it as a symbolic choice. This fox whose mother roams the “huge whisper of the constellations”, this orphaned-looking, “woebegone” little creature which is literally a vision of sorrow, had looked past the other people and then directly at Ted, choosing him from amongst the crowd. But Ted walked away and escaped “into the Underground”. In the light of all he ever wrote in his poetry and his prose about the importance of accepting irrational, instinctive, imaginative energies as they manifest themselves in our lives, it is no wonder that he later sees this choice as a mistake.

Had he “paid the price” and accepted the energies, what then? He leaves the question unanswered – as it must be, for there was no guarantee that the eventual outcome would have been different. But the choice he did make, which was to reject nature and instinct and to accept instead Sylvia’s goals of a house, domesticity, publication and public acclaim, he sees as critical and disastrous. He walked “As if out of my own life”. And he acted, as in ‘Ouija’, according to what he thought others (Sylvia, in this instance) might think and do and without considering that he might be mistaken.

The marriage between Ted and Sylvia, as is shown in Birthday Letters, was more than a legal contract. It was a questing partnership, an alchemical conjunction which, as in alchemy, needed to be tested again and again with Mercury and Sulphur (dissolve and coagulate is the repeated formula in alchemy) before the true spiritual gold could be achieved. This is what “comes with a fox”, this mercurial and sulphurous (the fox’s “old smell”) testing. And in refusing to accept this test, Ted effectively stopped the alchemical process and doomed their shared quest to failure.

The final lines of the poem state quite clearly that this was the point of no return. From then on in Birthday Letters the duality is fixed, the “marriage” is ended. This, then is the crossroads at which the “wrong fork” asked about a few poems later in the sequence (‘Error’, BL 122) was taken.

So, by the time the couple reach The Magician’s path in the World of Assiah they have moved very far in the wrong direction and the division between them has become more marked.

The Magician appears in various forms in ‘Fairy Tale’ (BL 159). One who is not mentioned by name but whose work was well-known to Ted and Sylvia and whose influence is most strongly felt in the poem is Dr John Dee. Dee (1527-1608), was an Elizabethan Magus who was court astrologer to Queen Elizabeth I. He taught Sir Philip Sidney (amongst others of the Court circle) and he was closely associated with that group of Sidney’s friends who were experimenting with the magical and mystical powers of measured verse8. Although Dee was a serious student of Mathematics, Cabbala, Hermeticism, Alchemy and Astrology and was highly esteemed by many scholars in England and Europe, he was deeply involved in the practice of natural magic and was commonly branded a conjurer.

With his skryer, the medium Edward Kelly, Dee practiced Cabbalistic angel-magic. It was angelic spirits which dictated to them the complex system of numbered and lettered tablets and the means of using these tablets to summon the forty-nine Angels, ‘Airs’ or ‘Aethers’, each of which, they believed, controlled some part of earthly existence. These forty-nine Angels can be represented on a Cabbalistic Tree in which each of the seven lower Sephiroth (those below the first three Sephiroth of the supernal triangle and occupying what is commonly termed ‘the abyss’) contains a similar tree of seven Sephiroth (or ‘palaces’, as they are sometimes called). The calls or invocations which summoned these forty-nine Angels were the keys to calling on their magical powers to open the ‘Gates of Understanding’. Forty-nine became John Dee’s magic number and he incorporated these angelic letters into the Great Seal which was his most important magic tool.

Forty-nine (so we are told in ‘Fairy Tale’) was also Sylvia’s magic number. There is no evidence of this in her published poems and stories or in her journals and letters to her mother. But duality is so woven into the fabric of this poem, and the Divine Source is so far from this World of Assiah, that it is often difficult to distinguish truth from illusion, white magic from black, fairy tale from reality. There is ample evidence in Shakespeare and the Goddess of Complete Being that Ted, himself, was very familiar with John Dee’s work and, in the poem, the couple clearly share the knowledge of Sylvia’s “high palace”, “there among the eagles” – or, at least, they share the knowledge of forty-eight of the rooms. The forty-ninth was to have been opened “some day, together”.

However, Ted, like a male version of Bluebeard’s wife, is allowed to explore only forty-eight rooms of Sylvia’s dream castle. The forty-ninth is forbidden to him. The imagery of dark, sexual power which runs beneath the Bluebeard story is here, too, but it is Sylvia who has the power. Like Hecate, the dark Moon Goddess of the Underworld who was believed to haunt crossroads and tombs, she flies off every night to meet her “Ogre lover” whose “voodoo carcass” is crammed with all her earlier lovers. The poem is full of paganism: of tarred, burning effigies which mean no more to Sylvia than a “child’s night-light”; of necromancy and deception. But, as in all the Birthday Letters poems, there are references to real events and situations too. Sylvia did write about her former boy-friends and lovers in her “secret journals”, and the one which burned brightest at the time she met Ted was Richard Sassoon. Now, in the poem, there are suggestions of promiscuity, hidden secrets and jealousy, all of which Ted “never saw” before, and all of which are characteristic of the malign powers of this World of Assiah, which can distort and corrupt human perception and behaviour.

There are Cabbalistic parallels, too, for of the forty-nine invocations which were given to Dee and Kelly – the forty-nine keys which were to open the Gates of Understanding and lead to the paths of Wisdom – only forty-eight were to be used. The forty-ninth was forbidden.

Nor were Dee and Kelly the only Cabbalists to know about the forty-nine keys to the Gates of Understanding, even at the time that Dee was recording his Angelic communications. There are many different accounts of these forty-nine levels of wisdom in Cabbala and they are essentially part of the Cabbalistic journey. Traditionally only a Magus, who has successfully opened all the Gates of Understanding and travelled all the Paths of Wisdom, may safely open the forty-ninth gate which leads back from the abyss to the Supernal levels and, specifically, to Sephira 3 (Binah: Understanding).

In Jewish Cabbala, for example, Moses was such a Magus. He was the Hermes figure: an able magician who carried the magic snake-staff and acted as God’s messenger. He was the only one of his people sufficiently spiritually prepared to be spoken to directly by God. And in Jewish lore, it was he who brought the Word of God to his people and who guided them through the forty-nine Gates of Understanding in order to bring them out of Egypt to the Promised Land. The ritual of the Counting of the omer, which is still part of Jewish Passover, celebrates this journey “from the brink of the spiritual abyss”9.

So, what are we to make of the information in ‘Fairy Tale’ that both Ted and Sylvia could open the forty-ninth door? Both, in Cabbalistic terms, must have passed through the forty-eight Gates of Understanding to be at this point, but we already know that along the way they had taken the “wrong fork”. They were therefore, not spiritually prepared for entrance to the Palace of Binah, which is the seat of Aima, the Great Goddess who is also Isis. For “the high initiate”, according to Aleister Crowley, “She is light and the body of light. She is the truth behind that veil of light. She is the soul of light”10. Like the sun, truth is powerful and dangerous, creative and destructive: like the sun, those who are exposed to it without careful preparation will be destroyed.

Throughout her journey to poetic rebirth (the struggle to find and release Ariel which Ted discusses in detail in ‘Sylvia Plath and her Journals’11) Sylvia had focussed on her own “deep and inclusive inner crisis”(WP 179). Her gaze was focussed inwards on her own life, on what she herself called “the old father-worship subject” (SPJ 19 Oct. 1959), on her “ogre lover”. The first stage of her rebirth, as Ted describes it, came from reassembling “the ruins of her mythical father”, a process which began for her with a dream (WP 182). The last stage, entailed confronting him “point blank” and “demythologising” him (WP 187). Her love for her father, whom she calls an “ogre” in one journal entry (SPJ 12 Dec. 1958), was the essence of that rebirth, and it is to this god/father that she flies in ‘Fairy Tale’.

Behind Sylvia’s Ariel poems, Ted wrote, was a vision of Paradise which “was eerily frightening, an unalterable spot-lit vision of death” (WP 161). He described the poetry of Ariel as “ the last flight of what we had been trying to get flying for a number of years”; then added, “But it dawned on me only in the last months which way it wanted to fly”. In Cabbalistic terms, Sylvia was not looking towards the Heavens. She was looking in the wrong direction.

For Ted, the focus for rebirth was always Nature: the life and death cycles and the energies of the natural world. His gaze had always been focussed outwards and towards the Goddess. So, like a magician in a fairy tale, a blade of grass is the skeleton key with which he opens the forty-ninth door: for what is a blade of grass but the simplest, humblest sign of Nature’s bounty and, as has already discussed, the power of simplicity is one of the things which must be learned on the Cabbalistic path. But he was clearly unprepared for the consequences of opening that door. What he glimpsed – what panicked him – was the terrifying dark aspect of truth, and both he and Sylvia plunged into the abyss.

Ted, who was always careful to protect himself with ritual and myth from the energies he summoned, fell into the abyss but was not altogether destroyed. Sylvia never protected herself in this way. Ted wrote that her “poetic genius and the active self were the same”, and that she “had none of the usual guards and remote controls to protect herself from her own reality”(UU 181)12. Sylvia was destroyed.

So again the poem encompasses the beginning and the end of the journey, and the dualities and the dangers which the journeyer must face on The Magician’s path.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

1. Ted Hughes was very familiar with these sources and was, in fact, translating works by Euripides and Aeschylus at the time that he was writing many of the Birthday Letters poems.

2.Two versions and notes about this song can be found at Traditional Songs. Thanks to Charles Cave and Ross Chambers for directing me to this link.

3. The day after I wrote this, Colin Low sent me this link to On Separation. His timing was uncanny and his essay beautifully links the veil of Isis with the cross which represents duality.

4. In his published review of this and another of Sylvia’s poems, Daniel Huws wrote of their “quaint and eclectic artfulness”, and (with supreme male-chauvinism, as if female beauty might influence a poem’s worth) “… my better half tells me “Fraud, fraud”, but I will not say so; who am I to know how beautiful she may be”. These quotations and Sylvia’s poem, ‘“Three Caryatids without a Portico” by Hugo Robus’, can be found in Keith Sagar’s book, The Laughter of Foxes (Liverpool University Press, 2000. pp. 48-9). Sylvia’s own reaction to “the clever reviewer” and to “Human rooks which say: Fraud” is in her journal and letters (SPJ Feb 19, 20, 1956; SPLH 2 Feb. 1956).

5. Daniel Huw’s poem ‘O Mountain’ (included in Noth, Secker and Warburg, London, 1972) was written as an elegy for Syliva. Lucas Myers confirmes this in his memoir Crow Steered Bergs Appeared (Proctor’s Hall, Sewanee, Tennessee ,2001. pp. 27-8).

6. Myriad: from the Greek murioi, meaning 10,000. Not only is this word the usual word used in translation of the Lao Tzu from the Chinese, it is also a very significant Cabbalistic number being made up of 10 (the number of the World) and 000 (the number of the Absolute – the Divine Source). The Mother of the myriad creatures is, of course, Nature and the Goddess.

7. For an account of this see ‘The Burnt Fox’ in Winter Pollen, pp8-9.

8. French, P. John Dee, Routledge & Kegan Paul, London, 1987.

9. Rabbi Yaakov Asher Sinclair, in a modern Internet magazine called ‘Seasons of the Moon’, writes of this ritual: “every night for seven weeks we count the days that have passed on this spiritual journey from Egypt to Sinai… “. (‘Seasons of the Moon’, Iyar, 5758 April 27, 1998 - May 25, 1998).

10. Crowley, A. The Book of Thoth, Weiser, NY, 1985. p73.

11. Hughes, T. ‘Sylvia Plath and Her Journals’, Winter Pollen, Faber, London, 1994. pp. 177-90

12. Hughes, T. ‘Sylvia Plath (1966)’ in Faas, E. (Ed) Ted Hughes: The Unaccommodated Universe, Black Sparrow Press, Santa Barbara, 1980)

Poetry and Magic text and illustrations. © Ann Skea 2001. For permission to quote any part of this document contact Dr Ann Skea at ann@skea.com