Poetry and Magic 3

Capriccio: The Path of the Sword.

Poetry and Magic 1 and 2 should be

read first unless the reader already has a good understanding of the serious

spiritual practice of Cabbala, and is familiar with the Cabbalistic Tree and the

Tarot cards associated with its Paths.

© Ann Skea

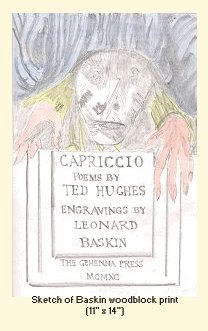

Introduction and ‘Capriccios’ (C 1)

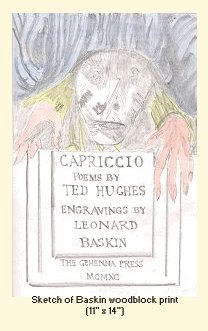

Capriccio was first published as a beautifully illustrated, leather

bound, limited edition of fifty books in the “unsettled Spring of

1990”1. Ted was in his

sixtieth year, which, astrologically, marks the return of the planet Saturn to the

position which it originally occupied in his birth-chart. As Ted would have known, this

signifies “a point of reckoning, a crucial stage in our personal

evolution… a time when boundaries are broken and outworn structures

abandoned.”. At sixty, this so-called ‘Saturn Return’

“marks our passage to being an elder2”.

Cabbalistically, too, 60 (6 x 10) shows the Goddess’s powers as doubled and

directed through Tiphereth (6 – Love) at the heart of the Tree, in such a way

that Malkuth (10 – The World) is joined to the Source3. This

particular Path, on the Pillar of Equilibrium, is the Path of the Arrow which a

Cabbalist will take at the completion of the Great Work.

Astrologically and Cabbalistically, therefore, it was appropriate that Ted should

have chosen his sixtieth year to begin to deal with the events in his life which, as he

told me when he first spoke about these poems, he “should have dealt with

earlier, but couldn’t”4.

In 1995, eight poems from Capriccio and eight poems from Birthday

Letters were included in a selection of ‘Uncollected’ poems in Ted

Hughes: New Selected Poems 1951-1994. Birthday Letters and a small limited

edition of poems, called Howls & Whispers, were not published until 1998,

eight years after Capriccio first appeared. All three sequences,

Capriccio, Birthday Letters and Howls & Whispers, were not

published together until five years after Ted’s death, when they appeared in

Ted Hughes: Collected Poems in 2003. Even then, the Capriccio poems were

separated from the other two sequences by more than 200 pages. So, apart from that

first linking in 1995 of these poems about Assia Wevill with poems about Sylvia Plath,

there was little but the biographical nature of the poems to suggest that all three

sequences were part of one complete cycle, or that the Capriccio poems might

have been a necessary part of Ted’s Cabbalistic journey.

Other things also hid this link from the casual observer5. Ted chose to

publish both Capriccio and Howls & Whispers as finely bound,

expensive, strictly limited editions, which included original woodcuts and etchings by

his friend Leonard Baskin and were published by Baskin’s Gehenna Press. A gap of

eight years separated the appearance of these two books. Few people, therefore, were in

a position to notice that the first poem of Capriccio (entitled

‘Capriccios’) was, with only the smallest of changes, identical with the

last poem of Howls & Whispers (‘Superstitions’).

Carol Bere did note this and she wrote that Capriccio, Birthday

Letters and Howls & Whispers could “be viewed as fragments of

one long sequence or, more accurately, as separate, although interrelated

sequences”. She noted the circular pattern of the sequences, too, and saw

this as suggesting “the impossibility of fulfilment of transforming or

completed myth”.

In Cabbala, however, quite the opposite is true. The completed circle marks the

fulfilment of the Cabbalist’s goal and the attainment of wholeness, harmony and

rebirth. So, the repetition of a poem at the start of Capriccio and at the end

of Howls & Whispers suggests that these two books were part of a single

Cabbalistic journey which, in this case, also included Birthday Letters. The

total number of poems in the three sequences (20 in Capriccio, 88 in Birthday

Letters, and 11 in Howls & Whispers) is 119, which, in Cabbalistic

numerology, reduces to 11, a Master Number which is “the great general number

of magic or energy tending to change.6 The energies of

11 hold the power of “attainment, supremacy and mastership” and bind

all opposites together to bring everything to equilibrium. And this is exactly what Ted

was attempting to do as he used his will, his imagination and all his poetic, shamanic

and Cabbalistic skills to re-member (in the literal and the common meaning of this

word) his relationship with Assia and Sylvia.

The seemingly small differences between the first poem in Capriccio and the

final poem of Howls & Whispers are significant, too, when the poems are seen

as part of the same healing journey. “You will be laughed at for your

superstitions” Ted warns in ‘Capriccios’ (C 1), at the

start of the journey. But in ‘Superstitions’ (H&W 11), when his

journey has been successfully completed, he is confident enough to scorn the opinion of

others: “Let them laugh”.

Ted certainly paid attention to superstitions. In a book review in 1964, he wrote:

“The major superstitions are impressive. They are so old, so unkillable and so

few. If they are pure nonsense, why aren’t there more of them? But they all keep

reviving with the perverse air of intuitions, never losing their central idea, no

matter how richly they proliferate in details.”(WP 51). The change of

title between the two poems encapsulates Ted’s awareness that those who deal with

supernatural powers (as a Cabbalist or shaman or even a priest must do) must pay

attention to seemingly capricious nature which superstition attributes to them, and his

final unconcern for those who regard superstitions as having no real foundation.

The only other difference between the two poems is similarly interesting. Speaking

of Frigga, the great Norse Goddess whose presence he invokes in the opening lines of

both poems by a threefold repetition of her name-day Friday (Freya’s Day, or

Frigga’s Day), he issues the command in ‘Capriccios’ to

“imagine the bride’s mirror/ In the form of a cauldron”. In

the tradition of ritual magic, this command is made to all participants, including the

speaker. “Call it”, he instructs (again speaking to himself and us)

“a cauldron / Of the soul’s rebirth”. Frigga is the Triple

Goddess: Bride, Mother and Layer-Out. Her element is the sea (the cauldron of all the

elements) the waters of which are associated with the human subconscious, the soul, and

with life and death. In this first poem of Ted’s journey, he invokes the Goddess

as the bride into whose cauldron/mirror he is about to peer as he searches her waters,

like his own creature, Wodwo, for roots, memories and understanding. In

‘Superstitions’, at the end of his journey, there is no such command, and

Frigga’s cauldron has become “The cauldron of Valhalla / where

warriors [and perhaps poets who have completed the heroic journey] are

reborn”.

Everything I wrote about ‘Superstitions’ when I dealt with it in

Poetry and Magic 2: Howls & Whispers applies equally to

‘Capriccios’. At the start and at the completion of his journey, Ted

invokes the Great Goddess in the person of Frigga, the Goddess of the Norse mythology

which he believed to be “much deeper in us, and truer to us, than the

Greek-Roman pantheons…” (WP 41). He summons her into our world

“Today” (which is the immediate and continuous present), and he

ensures her presence by repeating her name-day and the numinous number 13. In Cabbala,

13 is a supremely powerful number. It combines the energies of 1, 2 and 3 which, as the

Supernal Triangle at the Crown of the Tree, represent the ever-flowing forces of the

Source present in our world (SSN 105). It is the number of the Sacrificed King

(the Hanged Man in the Tarot pack), and of the Sacred Feminine which is represented by

the thirteenth letter of the Hebrew alphabet – Mem (water). The presence

of Mem, written and heard in the words ‘memory’ and

‘remember’, is coincidental, but the poetic and magical power of its

presence would not have been lost on Ted as he made his journey through

Capriccio, Birthday Letters and Howls & Whispers.

The title of the first poem of Ted’s journey is ‘Capriccios’ which

is the singular form of the word which Ted chose as the title for the whole sequence.

Dictionary definitions of this word refer to an artistic work in free form, a musical

improvisation, a work full of sudden changes, a freak, a fantasy. None of these

definitions is appropriate, either for Ted’s opening poem or for the whole

sequence, both of which are carefully structured, and serious in mood and theme.

‘Capriccio’, however, comes from seventeenth century Italian and is made up

of ‘capo’ (meaning ‘head’) and ‘riccio’, (meaning

‘hedgehog’). Hence, ‘capo-riccio’ means hedgehog-headed and

describes a head with the hair standing on end.  The images conjured up by this meaning are ones of surprise, shock,

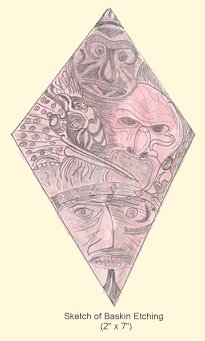

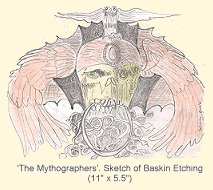

horror and terror. These are the images depicted, and elicited, by Goya’s

etchings Los Caprichos (The Caprices) (1793-1778). And similar nightmares and

horrors pervade Ted’s Capriccio poems and appear, too, in Baskin’s

accompanying illustrations.

The images conjured up by this meaning are ones of surprise, shock,

horror and terror. These are the images depicted, and elicited, by Goya’s

etchings Los Caprichos (The Caprices) (1793-1778). And similar nightmares and

horrors pervade Ted’s Capriccio poems and appear, too, in Baskin’s

accompanying illustrations.

Goya described Los Caprichos as “a criticism of human errors and

vices” and his serious purpose was to make rational and satirical comment on

the society in which he was living. In particular, the etching on which he included the

comment,

“The sleep of reason engenders monsters”, reflects

Ted’s own purpose in Capriccio, although Ted’s poems are not in any

way satirical. The cats, owls, and bats which become creatures of nightmare and

witchcraft as they loom from the darkness around the sleeping figure in Goya’s

etching are matched by the demons, monsters and skulls in Ted’s poems and in

Baskin’s accompanying engravings. As are the elements of unexpected horror and

death which pervade many of Goya’s other Los Caprichos pictures and convey

the monstrous, terrifying, topsy-turvy nature of a world where reason has been upset by

human passion and folly.

It is easy to imagine that

Ted, remembering his relationship with Assia, remembering their meeting and the turmoil

of events which followed, remembering Sylvia’s death, his own and Assia’s

chaotic emotions, and Assia and Shura’s deaths, might interpret this as the

result of the sleep of reason and, in particular, of his own irrational passions and

folly. In the only Birthday Letters poem which refers to Assia, he described how

“the dreamer in her” fell in love with “the

dreamer” in him: and how “the dreamer” in him fell in love

with her (‘Dreamers’. BL 157-8). In ‘The Pit and the

Stones’ in Capriccio, Ted writes of “his own weakness”.

And in ‘Capriccios’, he seems to suggest that the man and woman in the

poem, as recipients of Frigga’s “two-faced gift”, were the

pawns of capricious gods. In theory, one can always decline to accept a gift. But at

least, if one fears offending the gods in this way, one must heed the traditional

superstitious belief that the gods always require payment for their gifts. Whether or

not Ted and Assia were the pawns of capricious gods, the fact is that he and Assia did

fall in love and that everything in Capriccio portrays that love as the sleep of

reason and their mutual immersion in a sometimes nightmarish dream.

It is easy to imagine that

Ted, remembering his relationship with Assia, remembering their meeting and the turmoil

of events which followed, remembering Sylvia’s death, his own and Assia’s

chaotic emotions, and Assia and Shura’s deaths, might interpret this as the

result of the sleep of reason and, in particular, of his own irrational passions and

folly. In the only Birthday Letters poem which refers to Assia, he described how

“the dreamer in her” fell in love with “the

dreamer” in him: and how “the dreamer” in him fell in love

with her (‘Dreamers’. BL 157-8). In ‘The Pit and the

Stones’ in Capriccio, Ted writes of “his own weakness”.

And in ‘Capriccios’, he seems to suggest that the man and woman in the

poem, as recipients of Frigga’s “two-faced gift”, were the

pawns of capricious gods. In theory, one can always decline to accept a gift. But at

least, if one fears offending the gods in this way, one must heed the traditional

superstitious belief that the gods always require payment for their gifts. Whether or

not Ted and Assia were the pawns of capricious gods, the fact is that he and Assia did

fall in love and that everything in Capriccio portrays that love as the sleep of

reason and their mutual immersion in a sometimes nightmarish dream.

Yet, the Cabbalistic structure of the Capriccio sequence suggests that these

poems had a purpose beyond that of simply depicting the turmoil caused by irrational

passions.

If Capriccio was the first stage of Ted’s Cabbalistic journey, then

there was a compelling and highly rational magical purpose to his recollection (and

re-collection) of all the events, passions, turbulence and terrors of his years with

Assia. It is related to a Pathway on the Cabbalistic Tree which is known as the Path of

the Sword and it maps a journey which needs to be taken before the Path of Wisdom

(which Ted followed in Birthday Letters) and The Path of the Snake (which Ted

undertook in Howls & Whispers) are attempted.

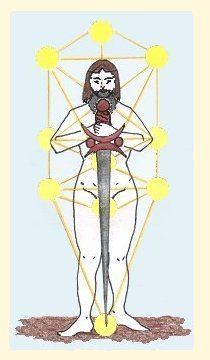

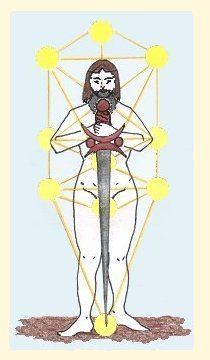

The Path of the Sword follows the Lightning Flash down the Sephirothic Tree, from

Sephira to Sephira, starting at Kether (1) and ending at Malkuth (10). This journey is

made in the World of Assiah, and it is made by a so-called ‘Crowned

Magician’ whose crown represents “the attainment of his

Work”7, and also, most

importantly, the ‘Crown’ of Supernal energies made by Sephiroth 1, 2 and 3

at the top of the Sephirothic Tree.

The Cabbalist’s Sword is “Reason…the analytical

faculty” , which is used to cut through “the complexity and chaos

caused in the heart”. It must be thrust into the Cabbalist’s own heart

to free “the perceptions from the Web of emotion”. Only in this way

can the simple truth be separated from the distorting emotions which may obscure the

clear perception of it.

Before any important Cabbalistic journey is undertaken, it is advisable, first, to

take The Path of the Sword in order to strike terror into and dominate any

‘demons’ (or disrupting, distorting thoughts and emotions) which might

break the continuous progress (or circle) of that journey. In the words of the

respected Jewish scholar of Cabbala, Gershom Scholem, the “ritual elimination

of negative factors that disturb the right order” is of utmost importance

and, particularly in Lurianic Cabbala, the purpose of many rituals is to control the

qlippothic demonic and satanic powers of “the other side”, which are

“at present mixed with all things and destroy them from

within”8.

Regardless of any Cabbalistic purpose, it is understandable that Ted should have

chosen to deal separately with the emotional years of his relationship with Assia

before immersing himself in memories of his life with Sylvia. In this way, he could

allow each woman her own poetic sequence and her own story. Had he not done this, the

revival of strong emotions as he wrote the poems and recalled, re-created and re-lived

the emotional turmoil of the period when Assia first entered his and Sylvia’s

lives, might well have prevented him from completing the sequence. At the very least,

his judgment would have been clouded and the sort of balanced view of all that had

happened which he sought to achieve might well have been impossible. So, in

Capriccio, Ted attempted to bring all possible emotional ‘demons’

under control before he embarked on what, for him, was clearly the most difficult and

dangerous task of remembering Sylvia.

The evidence that Birthday Letters and Howls & Whispers record

Ted’s Cabbalistic journey towards balance, harmony and wholeness is very strong,

as I have shown in my analysis of these sequences. So, too, is the possibility that

Capriccio represents his preparatory journey along the Path of the Sword. And it

is of special interest in this respect that in his New Selected Poems Ted

changed the word ‘canticles’ in ‘The Locket’ (C 2) to

‘Song of Songs’, thereby specifically referring to a canticle which has

very special meaning for Cabbalists and, in particular, for those who are of Jewish

descent, as Assia was.

The poems in Capriccio are dark and difficult poems, peopled by gods and

goddesses from many mythologies, and Ted deliberately chose to deal with their darkest

most demonic powers. But the tone of the poems is noticeably firmer, sharper and more

consistently objective than it is in Birthday Letters and Howls &

Whispers9. Ted does not

describe Assia: only her voice and her clothes. Nor does he conjure or evoke her in the

way he constantly conjures Sylvia in Birthday Letters, picturing her

brilliant-eyed at the birth of her child; bent at her desk writing; sitting amongst the

daffodils. As in Birthday Letters and Howls & Whispers, the woman in

Capriccio is not named but is ‘you’, ‘she’ or

‘her’, a device which hides individual identity and, as in Ted’s very

early poem ‘Song’ (THCP 24) allows him to conflate the woman with

the Muse/Goddess whose energies (as Ted believed) all women embody. Occasionally,

‘you’ seems to be used by the narrator as a form of self-address and/or to

include the reader or hearer of the poem, which further hinders specific identification

of the addressee. At times, too, the narrator distances himself even further from the

events, and ‘you’ and ‘I’ become ‘she’ and

‘he’.

These distancing measures also allow Capriccio to be less of a personal,

‘confessional’, indulgence and more like a myth in which readers may

recognize some elements as reflections of their own experiences. So, Capriccio,

like Birthday Letters and Howls & Whispers, may become “your

story, my story” and include us in Ted’s poetic, Cabbalistic and

shamanic ritual.

All of these devices may be seen as Ted’s deliberate and rational way of

cutting through the emotional turmoil which the revival of personal memories must

bring. But the creation and wielding of the Cabbalistic Sword also requires the utmost

balance and care, as the metaphorical description of the Sword suggests. Its

double-edged blade must be made of steel, the metal of Mars: so, it is used with

strength and ruthlessness. To balance this, the hilt must be of Copper, the metal of

Venus; and the guard shaped like her two crescent moons, waxing and waning: so Love

must be the motive and the guide of its use. Figuratively placed point-down on the

Sephirothic Tree, the pommel of the Sword is in Da’ath (the hidden Sephira,

Knowledge); the guard extends horizontally from Chesed (4) to Geburah (5) to combine

Mercy and Severity; and the point rests in Malkuth (10). The ‘Crown’ of the

Supernal Triangle must remain above the Cabbalist’s head to guide each individual

action. If this balance of strength, love and guidance is not present, then the

Cabbalist, as he plunges the Sword into his own heart, will destroy himself.

All of this, I must repeat, is imaginative metaphor for the task which must be

undertaken by all who seek Truth. It complies with the fundamental spiritual command to

all Truth seekers to ‘Know thyself’, and to do this it is necessary, first,

to understand their own hearts and their own actions.

‘The Locket’ (C 2)

‘The Locket’, at Chokmah (Sephira 2), is the second poem in

Capriccio and, from the opening lines on, it is full of dualities. "Sleeping

and waking” (the two states of existence) the woman is “half

blissful”. She lives, but death seems, initially, to be “utterly

within [her] power”. The locket itself, with its two halves sometimes

locked together, sometimes open but still firmly linked, provides a symbolic image for

all the dualities in the poem: life and death, male and female, entrapment and freedom,

the shifting balance in the poem between the two lovers, and the shifting balance of

power between the woman and death.

The woman who wears the locket could be Assia: the ‘I’ of the poem could

be Ted. But the reference to the Canticles in the opening line of the poem suggests

that, like the Canticle of Canticles (the Song of Songs10 in the Bible)

this whole poem has a double meaning.

For centuries, the inclusion of the Song of Songs in the Jewish and Christian

Biblical Canons has been debated because of its sensuous and erotic nature. Biblical

scholars hold that it is an allegory which expresses God’s love for His people,

and/or the love of each individual for God or Christ. The bride of the song is

variously interpreted as the community of Israel, the Shekinah, or a nun or female

worshiper: and the bridegroom is God or Christ. In the Song of Songs eros

(erotic love) is combined with agape (self-donating love), which, according to

Pope Benedict XVI, are the two halves of true Love11. Similarly,

in Jewish Cabbala, this marriage of what Scholem calls the “begetting and

receiving” potencies of God, constitutes the heiros gamos, the holy

union of male and female powers, and the female element in God is given worldly

existence in the Shekinah12. For

Cabbalists, therefore, the Song of Songs describes the marriage of Spirit with matter,

which first occurs at Chokmah (Sephira 2) on the Sephirothic Tree.

In ‘The Locket’, Ted’s mention of the spinster’s dreams of a

fiery cross has sexual and spiritual connotations which reflect the erotic yet

worshipful charge of the poetic dialogue in the Song of Songs. And in both, the

spiritual-material duality of Chokmah is clearly present. The love which is described

in ‘The Locket’, however, is erotic love, potent with feelings of ownership and power,

and with no sense of agape about it. And the gods in ‘The Locket’

are the gods of our fallen, demonized world, the gods of our human interpretation of

spiritual power, and the gods of mythology.

So, the god associated with Chokmah in ‘The Locket’ is Pluto, the Roman God of the

Underworld. He is ‘the bridegroom’, seeder of the land, and abductor of Persephone,

with whom he fell helplessly in love after being pierced by an arrow of Cupid/Eros at

Venus’s behest. Pluto’s number, for the Romans, was 2; his month was

February, the second month of the year. He was Lord of the Realm of the Dead, and

Charon, who is personified in ‘The Locket’ as Death, was gatekeeper to his

realm.

The woman in ‘The Locket’ is sensual, provocative and alluring, but she

is not the virginal bride of the Song of Songs, nor is she the maidenly Persephone.

Death lies in the locket between her breasts, and is “nursed”

– fed, like a witch’s “familiar”. And she keeps him,

like a “curio pet” (a very strange creature),

“trapped” and on a chain. Her feeling of power is manifest in the

way she teases life: taunts it with this death which is in her power: and also teases

death by biting the locket – placing its gold between her teeth, just as gold

coins were put in the mouths of the dead to pay Charon to ferry them to Pluto’s

realm.

She is a human woman with seductive, “Demonic” powers (in

THNSP the ‘D’ is capitalized and the word begins a line). But in

Cabbala the demonic is everywhere present in our fallen world, and it is especially

associated with the Shekinah.

The Zohar13, which is one

of the earliest and most important Hebrew Cabbalistic texts, states that

“There is a judgment that is severe and a judgment that is not severe. A

judgment that is balanced and a judgment that is not balanced.” The Shekinah,

which is the female aspect of God and the dwelling place of the human soul, embodies

both alternately, but these alternating phases are responsible for her separation or

exile from God. When the unbalanced power of severe judgment invades her, she becomes

the demonic, ‘Lower Mother’, the vehicle of severe punishment, and the

‘Tree of Death’ which is demonically cut off from the ‘Tree of

Life’.

According to Lurianic Cabbala, the Shekinah is freed from demonic forces

“only on the Sabbath when she puts on her sephirothic

garments”14. So, like the

Moon Goddess, the Shekinah has a bright and a dark face and the Zohar describes

this ambivalence (as Scholem notes) “with age-old lunar symbolism”:

“At times the Shekinah tastes the other, bitter side, and then her face is

dark”15.

The dark-faced Moon Goddess in Roman mythology, is Hecate who, like the Shekinah, is

known as the ‘Terrible Mother’. She is the female aspect of Pluto, Invincible Queen of

the Underworld with power over life and death, and the equal of Pluto in every respect.

She uses her demonic charms to enchant and bewitch men and cause obsession and madness.

And the demonic, seductive nature of the woman in ‘The Locket’, makes her a

true daughter of Hecate.

Assia, throughout Capriccio, is seen as the demonic, dark face of the

Shekinah, but this is only half her powers. We see nothing of the softer aspect of her

nature.

Like Assia, the woman in Ted’s poem has escaped from Berlin, from persecution,

and from death in a “long-cold oven / Locked with a swastika”.

Assia’s escape from Nazi Germany was made in the early 1930s “on the eve

of the second World War”16. Her father

was a Russian Jew; her mother a German Protestant. The family would already have

suffered some of the restrictions placed on Jews in Nazi Germany and although Assia was

still a child she would certainly have been old enough to be disturbed by her

parents’ worries, to share some of their fear, and to remember these things for

the rest of her life.

In ‘The Locket’, Ted talks of the woman’s beauty as a

“quarter-century posthumous”, which is the approximate length of

time between Assia’s escape from Berlin and her first meeting with Ted.

Assia’s death, too, was from gas from a long-cold oven. So, Ted’s poem

seems to suggest that Assia, when she died, was fulfilling a nightmare vision she had

always carried with her.

Whether or not this is true, it seems that having cheated Death once, the woman in

Ted’s poem felt powerful enough to control him. This irrational belief is always

doomed to failure: and in ‘The Locket’ it is constantly tested. The locket

in which the woman believes she has “trapped” Death keeps splitting

open, as if Death himself were teasing her, smiling at her, biding his time.

Ted, or the ‘I’ in the poem, remembers how he would close the locket,

bringing the two halves together again (thus restoring the equilibrium) and the woman

would smile. “I would close it. You would smile”: the two halves of

this line are carefully balanced, reflecting the interdependence of the man and woman.

But he remembers, too, that he did not hear or see the true situation. He believed that

their futures were linked and, like a bridegroom, he felt responsible, so he

“juggled” with them, as if maintaining a delicate balance which

might at any moment fall apart. But he did not see that his own relationship with this

woman was peripheral to that between her and the gods who hold the real power over life

and death.

In retrospect, it seems to him that the woman’s beauty had, as in a folk-tale,

been her bargaining chip with Death and had bought her “a quarter

century” more of life. It was a gamble on her part, but Death had only to

wait for the inevitable conclusion. And Death’s whisper “Fait

Accompli” – it is done and cannot be argued against – was always

there, unheard by either of them. If this phrase is read aloud in this poem, the

paronomasia of ‘fait’ and ‘fate’ suggests, also, the fated

outcome of any folktale wager.

Folktales are fantasies. They seem to be about our world and they have a sort of

logic of their own, follow an expected pattern, and often have a moral to impart. But,

like the “crooked key” to the woman’s locket, they are

distorted and offer us a distorted picture full of irrational, magical events. Yet, in

Cabbala, both the crooked key and the straight key are part of the fragmented whole of

our fallen world. Like life and death, like eros and agape, and like the

two halves of the locket itself, the crooked and the straight are inextricably linked

together. So, to understand the whole we need to see both and to accept their intimate

connection.

In ‘The Locket’, Ted reflected all the duality of Chokmah but, in

particular, he acknowledged its dark, qlippothic powers which, as in all the Sephira,

are married to the light.

‘The Mythographers’ (C 3)

The third poem of Capriccio, ‘The Mythographers’ occupies Sephira

3, Binah, seat of the All Mother who is also the Triple Goddess at her most

powerful.

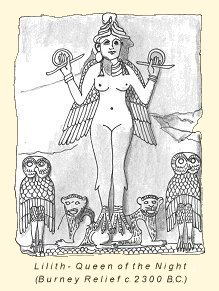

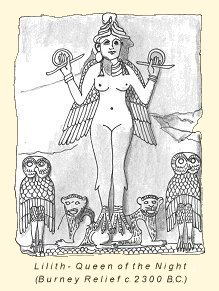

This poem is steeped in Hebrew Cabbalistic lore, especially that of the

Zohar, where both Lilith and Nehama (also written Na’amah) appear as

demonic seducers of men.

Lilith, in the Zohar, is also the dark demonic aspect of the Shekinah with

which she is inextricably entwined. And just as the Shekinah is personified as the

bride of Jehovah, and also of Adam Kadmon (the perfected Adam that Cabbalists strive to

become), so, Lilith the “whore” is the sexual partner of the fallen

Adam (Adam Belial) and the wife of the dark angel of the ‘other side’,

Sam’ael, Prince of Demons and Angel of Death17.

Sam’ael is twin brother of Metatron, the Archangel of Kether, ‘Sustainer

of Mankind’. He descended from Heaven to become Lord of the Underworld and, just

as the dark-faced, demonic Shekinah is separated from the Godhead because she embodies

severe judgment, he, too, represents the ‘Severity of God’. His first wife

is Lilith, Queen of the Night, who was once the first wife of Adam. His second consort

is Nehama, whose name means ‘comfort’ or ‘pleasing’.

Both Lilith and Nehama fly from the dark, demonic ‘other side’ to seduce

men. They “lead the sons of men astray, and dwell in the doorway of the house,

and in cisterns and latrines” 18. Lilith, true

to her moon-goddess nature, comes forth “month after month when the moon is

renewed in the world”19. She comes to

men in the night to seduce them in dreams and fantasies, and she bears demon children

from their spilt semen. Nehama, unlike Lilith, takes human form to seduce men with her

beauty and charms. But she, too, “makes sport with the sons of men, and

becomes hot for them in dreams, in that desire which a man has, and she clings to him,

and she takes the desire, and from it she conceives and brings forth other kinds into

the world”.

Lilith and Nehama appear also as

demonic powers in Neoplatonic Cabbala. There, they are rulers of the 7th Palace of

Darkness and they govern the qlippothic shells of Yesod (9) and Malkuth (10), the two

Sephiroth which are closest to the Underworld and in which both faces of the

Goddess’s lunar powers are strongest. There is a connection, too, between Lilith

and Frigga, because Lilith is known as the demon of Friday.

Lilith and Nehama appear also as

demonic powers in Neoplatonic Cabbala. There, they are rulers of the 7th Palace of

Darkness and they govern the qlippothic shells of Yesod (9) and Malkuth (10), the two

Sephiroth which are closest to the Underworld and in which both faces of the

Goddess’s lunar powers are strongest. There is a connection, too, between Lilith

and Frigga, because Lilith is known as the demon of Friday.

The parallels between all the various mythologies on which Ted drew in

Capriccio reflect his belief that myths are “tribal dreams of the

highest order of inspiration and truth, at their best”; stories which are

“uncannily similar all over the world” and which are like

“an archive of draft plans” (WP 152) for the sort of

imagination which can help us to understand our world and ourselves. He expressed this

belief many times, over many years, and in many ways: writing, at different times, that

myths embody “universal and human truths” (WP 138); that they

constitute a “pool of shared understandings” which represent a

deposit of “spiritual and psychological wealth” (WP 310); and

that they allow us to imaginatively enter “the realm of management between our

ordinary minds and our deepest life” (WP 41).

In ‘The Mythographers’, Ted tells the stories of Lilith and Nehama and

dramatizes the details given in the Zohar and in much earlier written and oral

mythologies. In these old myths there are obvious truths about human nature, human

wants and needs, human reactions to religious and social prohibitions related to

masturbation, promiscuity, the ‘wasting’ of semen, and about human

fantasies, fears and guilt. The stories of Lilith and Nehama, both of whom were

associated with marriage, seduction, adultery, the birth and death of children, dreams

and obsession, also had particular relevance to Ted’s own life and to his

relationship with Assia. And the fact that Lilith and Nehama shared Assia’s

Hebrew Judaic background, and that they represent the demonic face of the Shekinah, was

important.

It is clear, however, from a later poem in Capriccio,

(‘Fanaticism’ (C 7)) where Assia wears the quite different

“mask” of Aphrodite, that Lilith and Nehama represented only the

dark side of Assia’s nature. Most importantly from a Cabbalistic point of view,

by establishing these Demon Queens on the Sephirothic Tree at Binah (3), which is part

of Supernal Triangle which ‘Crowns’ the Path of the Sword, Ted was marrying

the energies of the All Mother (3) with those of the All Father at Chokmah (2) and

joining both to the Source at Kether (1). Also, in establishing the Underworld deities

at these Sephiroth, he was deliberately choosing to enter and probe the ‘other

side’, for, as the Zohar puts it, “one who is saved from there is a

loved one, a chosen one of the Blessed Holy One”20: and only in

this way can the Shekinah be reunited with God, and unity and harmony be restored.

God, in ‘The Mythographers’ is the creator of Adam and Eve, our

primordial parents. But, in trying to understand the human condition and

“testing it”, so-to-speak, in various stories to see which held the

most truth and offered people the most insight, the mythographers created Lilith and

Nehama. Lilith’s story is at least as old as the earliest Mesopotamian writings,

where she appears as a willow-tree demon in the Gilgamesh Epic. In later myths she is

Adam’s first wife who, having been created from earth at the same time as him,

regards herself as his equal and refuses to obey him and lie beneath him. Uttering the

name of God, she flies off and leaves him. At God’s intervention, and because she

refuses to return to Adam, she is banished ‘below’ and becomes a demon who

must deliver to God 100 of her offspring each day. So, she preys on unprotected

children, and she visits men in their dreams, arouses them or copulates with them, and

bears hundreds of children from their spilt sperm. Those who are not delivered to God

as payment for leaving Adam, she brings up as spirits and demons. She is sometimes a

screech-owl; and she is sometimes a hairy night-monster. She is known as

‘Primordial Lilith’, ‘Ancient Lilith’, ‘Grandmother

Lilith the Great’, ‘Great Whore’, ‘Tortuous Serpent’, and

‘Blind Dragon’. And she is immortal.

Lilith, in Ted’s poem is all of these things. She is a willow-dwelling

screech-owl. “Her abortions” are the spilt sperm of the men she

visits in dreams. And, because of her, a couple may remain childless and

‘free’ for each other. She comes to men in the darkness, arouses them, and,

as they stroke the hairs on her legs21, she detects

the “Mayday signal” (‘Mayday’, which is the international call-sign

for help, here refers both to the man’s urgent need for sexual relief and to

pagan May Day fertility rites) under rings which no longer represent the harmonious

unity of marriage but are simply “finger rings” (the paronomasia

with ‘fingerings’ reflects the man’s actions). Laughing, Lilith

seduces the man, and he, feverish in his fantasies, hallucinates her sexual voracity

and her domination of him. She “rides him”, and he is helpless to

resist her: so, his guilt is assuaged. Human psychology, common sexual and emotional

needs, social and religious pressures, and guilt, all make this myth compelling and

have ensured its survival. Amongst some superstitious Jewish people, rituals and

talismans are still used to banish Lilith from their bedrooms and to protect their

new-born children.

The myths about Nehama are similarly compelling and offer similar comfort to

guilt-ridden men and women caught up in the chaos caused by powerful sexual drives and

deep emotional needs. Nehama first appears in the Bible (Genesis 4:22) as the

descendent of Cain and sister of the first artificer in metal, Tubal Cain. Since Cain

was banished from the earth by God and, therefore, belongs to the qlippothic

‘other side’, Nehama is a demon and she, like Lilith, is immortal. In the

Zohar, it is said that after Cain’s death, Adam kept separate from his

wife, Eve, for 130 years, and that two female spirits, Lilith and Nehama came to

copulate with him and bore demon children. But Adam was not Nehama’s only

conquest. Because of her beauty, “the sons of God went astray after

her” and, “to this day, she exists and her abode is among the waves

of the great sea. And she comes forth and makes sport with the sons of

man”22.

Unlike Lilith, Nehama does not want the children she bears and “all of them

go to Lilith the Ancient, and she rears them”23. And unlike

Lilith, Nehama takes human form in order to have adulterous relationships with men. She

is the consort of Sam’ael and is “always included with him”

but she is said to have comforted Adam and Noah, Abraham and Isaac. In the Bible

(Proverbs 7) and in similar verses in the Zohar, she is described as a predatory

adulteress, who bedecks herself “like a harlot” with jewellery and

perfume to entice “the simple ones”, young men who (like the man in

Ted’s poem) are “devoid of understanding”. She woos them with

kisses “in the black dark night”, saying “Come let us take

our fill of love until the morning: Let us solace ourselves with loves”. So,

although “her house is the way to hell”, “with her fair

speech” she causes men to yield.

Nehama, in Ted’s poem is just like this but she is also subtly different. She

has not just appeared in human form, she has taken over “some woman’s

divorced and desperate body”, which become a living

“corpse”, a “shadow”, a “tailor’s

dummy”. The man is a “simpleton”. Like Adam, he has

“quit” his wife. But the reason Ted gives for his having done this

makes little sense unless the word ‘television’ is broken down to its root

meaning and the position of this poem at Binah, the seat of the Great Goddess on the

Sephirothic Tree, is taken into account. If this is done, ‘tele’ (Greek for

‘at a distance’) vision suggests that the man had visionary powers which

allowed him to see through the veil of illusion which hides the Truth in our world and

which is created and guarded by Binah. Beyond the veil of Binah is wisdom,

understanding and Truth. This is what Nehama seems to offer this man, and she uses all

her charms to “numb him” to any rational or moral

“pangs” which might distract him, and to convince him that

“he’s found it”.

Assia Wevill was twice divorced and she was still married to David Wevill when the

relationship between her and Ted began. Ted, too, was still married to Sylvia, although

they would soon separate. So, the relationship between Assia and Ted was adulterous.

Assia, according to most reports, was an intelligent and attractive woman who wore

stylish clothes and expensive perfumes. She had, it seems, boasted to friends that she

would seduce Ted. She worried about losing her looks and, until Shura was born, she had

never wanted children. She was also a displaced person who had been born in a country

which was, shortly afterwards, at war with Britain, so, in the common English

expression of the times she came from the “other side”, although the accent

she had acquired since leaving Germany disguised this. Her father was Jewish, and

Ted’s imagery in this poem draws on the religious practice of some Jewish women

who shave their heads and wear wigs, but there is no evidence that Assia ever adopted

this practice.

The parallels between the woman in this poem and Assia Wevill are remarkable. But

this is partly because the myth of Nehama is based on a common human scenario. It is

also because Ted chose to pick out only those things about Assia which fitted his

Cabbalistic purpose and established the deities of the Underworld as his

‘Crown’ for this Path of the Sword.

In any case, whether the woman in this poem is taken to be Assia or not, this woman

is possessed by Nehama. It is Nehama who does not want to be pregnant and who sees and

fears the skull beneath the skin of the suckling baby. It is Nehama (who is immortal)

who smells death and corruption in the woman whose body she occupies, and is horrified

by it. And it is Nehama who sacrifices the “baby-skull” and goes

through “Death’s oven-door” with the child and the woman to

give that child to Grandmother Lilith.

Nehama, like the wig on the tailor’s dummy, is a simulacrum of a real, living

thing; a decorative but false temporary adornment: but the woman and the man are human,

and so must die. In the structure of Ted’s poem, the break which separates

“Let it watch her” from “In the Irish mirror”,

but which is not reinforced by punctuation, effectively allows both the mortals in this

poem (the possessed woman and the wretched bridegroom who “understands

nothing”) to be reflected in the “Irish mirror”. Magical

mirrors that reveal the truth or the future are common in Irish mythology, and in this

one the image of both mortals is that of a skull grinning down.

The merging of myth and fact in this poem is chilling and awesome, but that Ted

intended the woman in the poem to be not just Assia but also a manifestation of the

Great Goddess in human form, is reinforced by two other images.

The first, like the suggestion that the man quit his wife because of the

truth-revealing power of television, is awkward and out of place if taken at face

value. Nehama’s “fingers/ Her knees, her armpits” are

described as “flying/ Buttresses of Dover Cliffs”. We may imagine

limbs as white as the Dover chalk, but there would have been many better and more

appropriate ways of describing this, and Ted was certainly capable of finding one.

Chalky whiteness and the link with the sea must have been important to him here, and

both, as he well knew are associated with Leucothea, the White Goddess. She, like

Nehama, once had human form. She, too, killed herself and her child. She, too, was

given immortality as a goddess of the sea. And she, too, buttressed (in a manner of

speaking) and supported men in distress: most notably, when she gave Odysseus her veil

to use as protection when Poseidon’s storms threatened to drown him. The full

story of Leucothea is told by Robert Graves in Greek Myths24. But he wrote

of her, too, in The White Goddess, and also of another Goddess, Leucippe (White

Mare), who appears later in the Capriccio sequence as the

“familiar” of the woman in the poems25.

The second image which links the woman/Nehama to the Great Goddess is the final

image of the poem, in which “Her last / backward glance / seals a

star” between the bridegroom’s eyes. Certainly, events may well have

marked the man’s forehead with a permanent star-like frown. But for Cabbalists a

seal has magical power26. And the star

is the most important symbol of the Goddess, present on images of her from the earliest

Mesopotamian clay tablets to the most recent religious paintings and

icons27. Between the

eyes, too, is a point of mystical significance: it is the place of the Third Eye, the

Ajan chakra, the locus of energies associated with intuitive insight, spirit-to-spirit

communication, and with our deepest spiritual powers. So, in effect, the Goddess marked

this man as one of her chosen: one called to serve her and one with whom she might

communicate directly. In Ted’s mythological understanding, even such a glancing

choice as this would have been equivalent to a shamanic call.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

1. Publication details on the endpage of Capriccio: Poems by Ted Hughes,

Engravings by Leonard Baskin, The Gehenna Press, 1990.)

2. Neil Spencer, True as the Stars Above, Gollacz, London, 2000. pp.51-2.

3. In Cabbala, 3 is the number of the Goddess at Binah, and of the Path of the High

Priestess in Tarot. It is a mystical number which combines the divine power of 1 with

the force of 2 and brings them into dynamic equilibrium. 6 = 3 x 2: the Goddess’s

powers doubled. It is common Cabbalistic practice to refer to numbers by digits rather

than by words.

4. Ann Skea, diary notes of a conversation with Ted Hughes in 1995. These notebooks

are now in the British Library archives.

5. Carol Bere noted it in a scholarly paper in 1992, but her paper did not appear in

print until 2004. Bere, C. ‘Complicated with Old Ghosts’, in Moulin (Ed.) Ted

Hughes: Alternative Horizons, Routledge, London, 2004. pp. 29-37.

6. Heline, C. The Sacred Science of Numbers, DeVorss, CA, 1997. p. 93. This

book will be referred to in the text as SSN.

7. Crowley discusses the Cabbalist’s Sword in detail in Ch. VIII, ‘The Sword’, of

his Magick, Book IV.

8. Scholem, G. On the Kabbalah and its Symbolism, Schocken Books, New York,

1969. pp. 128-9.

9. Carol Bere noted that the tone of the narrative voice in Capriccio is less

“intimate” and “conversational” than in

Birthday Letters and Howls & Whispers and that “the speaker

tends to be more of a passive respondent”. ‘Complicated with Old

Ghosts’, op.cit. p. 37.

10. ‘Canticles’ appears in the original 1990, Gehenna Press publication. Ted changed

this to ‘Song of Songs’ in Ted Hughes: New Selected Poems 1951-1994.

11. Pope Benedict XVI’s 2006 Encyclical, ‘God is Love’. Catholic Encyclopedia

(https://www.newadvent.org/cathen/03302a.htm).

12. Scholem’s discussion of this aspect of Cabbala in On the Kabbala and its

Symbolism, op. cit. pp. 104-9, is invaluable background reading for

understanding Ted’s linking of Assia with demonic powers in Capriccio.

13. The Zohar or Book of Splendour is a collection of texts which are mostly

commentaries on the Jewish Torah and on the unseen mysteries therein. It is

generally believed to have been transcribed from earlier documents by the Spanish Jew,

Moses de Leon in the 13th century.

14. Scholem, On the Kabbala and its Symbolism, op. cit. p. 59.

15. ibid. p.107.

16. Feinstein, E. Ted Hughes: The Life of a Poet, Weidenfeld & Nicholson,

London, 2001, p. 120.

17. Raphael Patai, Sitrei Torah 1:147b-8, at

(https://ccat.sas.upenn.edu/~humm/Topic/Lilith/Index.html).

“The male is called Sam’ael

his female is always included within him.

Just as it is on the side of holiness,

so it is on the other side.”

18. Ibid. Zohar 3:76b-77a

19. Ibid.

20. Ibid. 1:147b-148b.

21. It is said that King Solomon became convinced that the seductive and exotic

Queen of Sheba was actually Lilith, because of the hair on her legs.

22. Zohar, op. cit. 3:76b-77a.

23. Ibid.

24. Graves, R. Greek Myths, Cassell, London, 1955.

25. ‘Familiar’ (C 18).

26. Seals have always conveyed power. Seals are still used to authorize documents,

and to represent the authority of a person or even, in business, an incorporated body.

Similarly, magical seals are believed to convey the power of whichever god’s

symbol (or ‘signature’) is on them.

27. In Christian iconography, both star and moon are commonly associated with the

Virgin Mary: the Goddess’s eight pointed star often appears on her robes; the

crescent moon beneath her feet.

The images conjured up by this meaning are ones of surprise, shock,

horror and terror. These are the images depicted, and elicited, by Goya’s

etchings Los Caprichos (The Caprices) (1793-1778). And similar nightmares and

horrors pervade Ted’s Capriccio poems and appear, too, in Baskin’s

accompanying illustrations.

The images conjured up by this meaning are ones of surprise, shock,

horror and terror. These are the images depicted, and elicited, by Goya’s

etchings Los Caprichos (The Caprices) (1793-1778). And similar nightmares and

horrors pervade Ted’s Capriccio poems and appear, too, in Baskin’s

accompanying illustrations.

It is easy to imagine that

Ted, remembering his relationship with Assia, remembering their meeting and the turmoil

of events which followed, remembering Sylvia’s death, his own and Assia’s

chaotic emotions, and Assia and Shura’s deaths, might interpret this as the

result of the sleep of reason and, in particular, of his own irrational passions and

folly. In the only Birthday Letters poem which refers to Assia, he described how

“the dreamer in her” fell in love with “the

dreamer” in him: and how “the dreamer” in him fell in love

with her (‘Dreamers’. BL 157-8). In ‘The Pit and the

Stones’ in Capriccio, Ted writes of “his own weakness”.

And in ‘Capriccios’, he seems to suggest that the man and woman in the

poem, as recipients of Frigga’s “two-faced gift”, were the

pawns of capricious gods. In theory, one can always decline to accept a gift. But at

least, if one fears offending the gods in this way, one must heed the traditional

superstitious belief that the gods always require payment for their gifts. Whether or

not Ted and Assia were the pawns of capricious gods, the fact is that he and Assia did

fall in love and that everything in Capriccio portrays that love as the sleep of

reason and their mutual immersion in a sometimes nightmarish dream.

It is easy to imagine that

Ted, remembering his relationship with Assia, remembering their meeting and the turmoil

of events which followed, remembering Sylvia’s death, his own and Assia’s

chaotic emotions, and Assia and Shura’s deaths, might interpret this as the

result of the sleep of reason and, in particular, of his own irrational passions and

folly. In the only Birthday Letters poem which refers to Assia, he described how

“the dreamer in her” fell in love with “the

dreamer” in him: and how “the dreamer” in him fell in love

with her (‘Dreamers’. BL 157-8). In ‘The Pit and the

Stones’ in Capriccio, Ted writes of “his own weakness”.

And in ‘Capriccios’, he seems to suggest that the man and woman in the

poem, as recipients of Frigga’s “two-faced gift”, were the

pawns of capricious gods. In theory, one can always decline to accept a gift. But at

least, if one fears offending the gods in this way, one must heed the traditional

superstitious belief that the gods always require payment for their gifts. Whether or

not Ted and Assia were the pawns of capricious gods, the fact is that he and Assia did

fall in love and that everything in Capriccio portrays that love as the sleep of

reason and their mutual immersion in a sometimes nightmarish dream.

Lilith and Nehama appear also as

demonic powers in Neoplatonic Cabbala. There, they are rulers of the 7th Palace of

Darkness and they govern the qlippothic shells of Yesod (9) and Malkuth (10), the two

Sephiroth which are closest to the Underworld and in which both faces of the

Goddess’s lunar powers are strongest. There is a connection, too, between Lilith

and Frigga, because Lilith is known as the demon of Friday.

Lilith and Nehama appear also as

demonic powers in Neoplatonic Cabbala. There, they are rulers of the 7th Palace of

Darkness and they govern the qlippothic shells of Yesod (9) and Malkuth (10), the two

Sephiroth which are closest to the Underworld and in which both faces of the

Goddess’s lunar powers are strongest. There is a connection, too, between Lilith

and Frigga, because Lilith is known as the demon of Friday.