‘Systole-Diastole’ (C 4)

‘Systole-Diastole’ is the fourth poem of Capriccio. It lies at Chesed, Sephira 4, the Sephira of Mercy, Love and Sorrow, and it represents one end of the Venusian guard on the hilt of the Cabbalist’s Sword. At the other end of this guard is Gevurah, Sephira 5, the seat of Justice, Severity, Strength and Fear. Between these two Sephiroth, the energies of Justice and Mercy alternate, like the two beats of the heart – systole-diastole (contraction – relaxation) – and, as for the heart, the harmonious balance of this rhythmic pulse is essential.

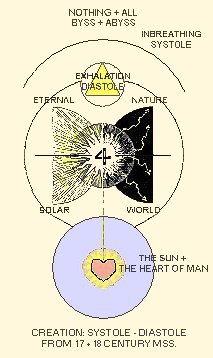

Systole-diastole, in this poem, describes the beat of the heart which is the subject of the poem. But in Cabbala and Alchemy, ‘systole-diastole’ has very specific meaning. It represents the bi-polar forces which govern the Universe and which, like the energies of Chesed and Gevurah, exist in dynamic equilibrium.

In Lurian Cabbala, in particular, systole-diastole is related to the original Creation and the pneumatic inbreathing (tsimtsum or contraction) which preceded the first exhalation of the Word. It is related, too, to the powers of judgment.

In the tsimtsum, as the Jewish scholar of Cabbala , Gershom Scholem, writes: “the powers of judgment which in God’s essence were united in infinite harmony with the ‘roots’ of all other potencies, are gathered and concentrated in a single point, namely, the primordial space, or pleroma, from which God withdraws”1. This original contraction was followed by exhalation and the “smelting out” of the powers of stern judgment from God’s essence into primordial space where they were mixed with a residue of God’s infinite light. Thus the ‘shells’, or qlippothic energies, came into existence. And although God remains hidden, his infinite light still “breaks through and falls into primordial space” as the lightning flash which creates and energizes the Sephirothic Tree. Most importantly, this process of contraction and emanation is continuous, for “Everything that comes into being after the ray of light from ein-sof has been sent out into the pleroma is affected by the twofold movement of the perpetual renewed tsimtsum and of the outward flowing emanation”.

Isaac Luria (1534-1572) drew his concept of tsimtsum from treatises older than the Zohar, but it is still controversial. In the context of the Path of the Sword, however, its explanation of the existence of qlippothic, unbalance energies and of the existence of stern judgment and its attendant evils is important.

In other versions of the Creation myth, inbreathing and exhalation (systole-diastole) produce the world of light and the world of darkness and all other dualities. And the energies of the Source reach the human heart in systolic-diastolic rhythm2.

The heart is the seat of the Soul and the place of intersection between God and Man. This Divine-Human relationship is represented by the cross + which is the symbol of 4 – the mystical number of the Eternal Principle of Creation, the Door to Illumination and the number of Chesed.

Quoting Saint Martin on the subject of mystical numerology, Corinne Heline writes: “we are given to understand that 4 belongs properly to the Logos, the word that was in the Beginning, or in other words, to the World of Creation” (SSN 28). And since 4 also governs human creative abilities when they are “focused in the spiritual” (SSN 27) it is wholly appropriate that Ted’s poem, ‘Systole-Diastole’, should rest at Sephira 4 (Chesed) on the Sephirothic Tree.

There is a direct relationship, too, between ‘The

Mythographers’(C 3) and ‘Systole-Diastole’, for not only is

“the symbol of Four the Star” (SSN 32), but 4 is also the

number associated with those who, like the shaman, have “qualified for that

high and noble calling of conscious invisible helpership” (SSN 33).

So, the star with which the Goddess sealed the brow of the

“bridegroom” in ‘The Mythographers’, thus marking him as

her chosen one, continues to shine through the mystical number 4 at Chesed. And the

Goddess herself is present in ‘Systole-Diastole’ as the Star-Goddess,

Astarte, whose symbol in her dark manifestation as Goddess of War is a lioness. This

Goddess’s ‘call’, which was described in ‘The

Mythographers’, becomes in ‘Systole-Diastole’ a heart-devouring

demand which, it seems, the protagonist initially tries to resist.

The opening lines of the poem state his dilemma. “Heart was the difficulty”. Heart, as the seat of the Soul, is the “god-head of the body”, the place where the Goddess, “the mother”, communicates directly and intuitively, spirit-to-spirit, with her children. But the “child” in this poem is reluctant to accept her demands.

To begin with, he is aware of her presence only as physical symptoms. His heart kicks, wrenches “to be free” of his body. It becomes “a panic heart”, its disturbed rhythm “bruising his ribs / Making his back ache”. The lioness, Astarte, as a demonic Goddess of War drinks human blood. But because this is the dark face of the Goddess of Love, she is, in Cabbalistic terms, the exiled Shekinah and, so, “thirsts for spirit” so that she may be reunited with God. For Cabbalists and Alchemists, and in many other spiritual beliefs, there exists in Man’s heart that “drop of spirit” which links him with God, but the demonic qlippothic excess of the lion/Goddess in this poem turns Chesed’s energies of love and mercy to devouring, “ravenous”, possessive and merciless lust.

The unrhymed triplets of Ted’s poem reinforce the Goddess’s presence, since 3 is her number. And the ambiguity created by lack of punctuation and enjambment binds the Goddess and the protagonist together, so that soul is clamped to soul in an iron grip that “no bodily force/ Could prise open”. “He”, the bridegroom of the Goddess- Shekinah, cannot escape her grip. So, trying some “desperate magic” he rips his “deranged heart the torn god” free and hides it “in the belly / Of a flower, where pollen might repair it”.

Many things about his poem find parallels in Ted’s life. In September 1961, shortly after he and Sylvia had moved to Devon, he did indeed suffer from violent heart fibrillations, which he also described in ‘The Lodger’ in Birthday Letters (BL 124. THCP 1124). Throughout Birthday Letters and Howls & Whispers Ted identified Sylvia with the Goddess; and we know from Sylvia’s letters, journal and poems that she was possessive, jealous and unrelenting in her fierce, devouring love for Ted. So, it is tempting to see her as the Goddess in ‘Systole-Diastole’ and to read the poem as a description of that specific time in late 1962 when Ted and Assia began their relationship, and, according to Lucas Myers, Ted “decided not to die. [and] The fibrillations stopped immediately”3. Perhaps, too, the exotic flowers in ‘Systole-Diastole’ symbolize Assia, whose exotic beauty has frequently been noted.

Such an interpretation would make sense of the death of the lioness-Goddess (Sylvia) and of her ghost, which “tore up the flower” (suggesting Assia’s destruction, rather as Ted describes it in ‘The Error’ (C 17)) and which, with “ghost-fangs”, retrieved his heart and carried it “back to her lair, in his chest” to “gnaw at it, lick at it, guard it” for her own purposes. It suggests, too, an explanation for the words of Sylvia’s ghost in ‘The Offers’ (H&W 10, THCP 1183): “Don’t fail me”.

However, whether or not Ted intended such a parallel, there is a Cabbalistic interpretation of the poem which is entirely consistent with its position at Chesed and, especially, with the underlying myth which Ted traced in Shakespeare and the Goddess of Complete Being, in which he discerned and described Cabbalistic themes4.

In this myth, flowers have very specific meaning which is related to the wrath of the jealous Goddess (in her dark, Underworld manifestation); the death of her bridegroom (who has rejected her); and his transformation into a flower, from which he is subsequently reborn to unite with her in her aspect of Goddess of Love. As Ted wrote in Shakespeare and the Goddess… , the flower is: “a daemon of the Goddess – moving (like God’s will) in a mysterious way, to accomplish her ends… to break down the one who rejects her, and force him to atone, finally returning him to Divine Love” (SGCB 476).

And in a long footnote, in which he demonstrated his familiarity with both Christian and Hebrew Cabbala, Ted noted: “In Hebrew Cabbala the highest Sephirah the Divine Source, from which the lightning flash of creative power enters the structure of materialization, is both God and his female form, the Shekinah… . In the Christian Cabbala (… ) the Shekinah becomes the Great Goddess” (SGCB 478).

So, in Cabbalistic terms, through rebirth from the flower and reunion with the Goddess, the Shekinah is rescued from exile and the male-female wholeness of the Godhead is restored.

In ‘Systole-Diastole’, the Goddess-tormented lover chose to bury his heart in flowers. But he was mistaken in believing that this would hide it from the Goddess, since flowers, too, are a product of her energies in our world, although they reflect her bright, fertile face rather that her demonic aspect. And there is special irony and significance in his comment that he “almost” chose the lotus for a hiding place, since the flowering lotus is widely accepted as a symbol of spiritual rebirth.

In the lover’s evasive action, Ted suggests his ‘false ego’- his self-deluding belief that he can choose, so easily, to escape the Goddess’s summons–and also his foolish naivety. But the Goddess is persistent, and having found his heart she will continue to “gnaw at it, lick at it, guard it” until he learns from his mistakes, sacrifices his ego (as does the shaman when he metaphorically becomes a skeleton in his descent to the Underworld), and accepts the redemptive task for which she has chosen him.

There is a strong suggestion in all this that Ted did regard himself as a shamanic poet and that he came to see the events of his life not only as resulting from his own mistakes but also from false ego and an unwillingness to give himself wholly to the Goddess’s work.

Perhaps (and this is speculation) he came to see the terrible things which happened as the sacrifice which the Goddess decreed he must make in order to learn not to reject her demands. Hence, the constant suggestion in the Capriccio, Birthday Letters, and Howls & Whispers sequences, that fate was responsible for all that happened. However, there is also a strong Cabbalistic theme underlying the biographical story in these sequences, and what this theme shows is that Ted and Sylvia and Assia each had choices to make, false ego to deal with, and important lessons to learn, and that all that occurred was the result of the qlippothic, but completely human, errors of all three.

‘Descent’ (C 5)

‘Descent’, which is the fifth poem of Capriccio, occupies Sephira 5, Gevurah (Judgment) on the Sephirothic Tree. It represents the other end of the Sword’s Venusian guard to that at Chesed; and Gevurah’s energies of Strength and Severity alternate with Chesed’s energies of Mercy and Love.

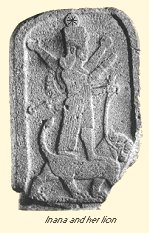

The qlippothic energies of Gevurah are those of severe judgment, and in ‘Descent’ they are wielded by the Sumerian Goddess of Love and War, Inana, and her dark sister Erec-ki-gala , the ruler of the Underworld. Together, as twin Goddesses, they are the Sumerian equivalent of Astarte. Inana is named in Ted’s poem: Erec-ki-gala is not. But the progressive stripping off of the seven symbolic articles of apparel which the woman in the poem undergoes, has an exact parallel in the Sumerian text which describes Inana’s descent into her sister’s Underworld realm5.

When Inana arrived at the gates of the Underworld “she pushed aggressively at the door.… She shouted aggressively at the gate”(ETCSL 73-77). Neti, the Chief Doorman, questioned her and bad her wait, then he went to his mistress Erec-ki-gala. “It is Inana, your sister”, he told her. And he described Inana’s aggressive behaviour and her appearance:

“She has taken the seven divine powers. She has collected the divine powers and grasped them in her hand. She has come on her way with all the good divine powers. She has put a turban, headgear for the open country, on her head. She has taken a wig for her forehead. She has hung small lapis-lazuli beads around her neck” (ETCSL 102-107).

“She has placed twin egg-shaped beads on her breast. She has covered her body with the pala dress of ladyship. She has placed mascara which is called “Let a man come” on her eyes. She has pulled the pectoral which is called “Come, man, come” over her breast. She has placed a golden ring on her hand. She is holding the lapis–lazuli measuring rod and measuring line in her hand” (ETCSL 108-113).

Erec-ki-gala then instructed Neti to bolt the seven gates of the Underworld, then to open them one-by-one. So, the progressive stripping away of all Inana wore and carried with her began:

“And when Inana entered...the first gate the turban, headgear for the open country, was removed from her head. “What is this?”. “Be satisfied, Inana, a divine power of the underworld had been fulfilled. Inana, you must not open your mouth against the rites of the underworld”.

“When she entered the second gate, the small lapis-lazuli beads were removed from her neck. “What is this?”. “Be satisfied, Inana, a divine power of the underworld has been fulfilled. You must not open your mouth against the rites of the underworld” (ETCSL 129-143).

And so, at each of the seven gates, the ritual disrobement, question and answer were repeated until Inana was naked. Still she challenged Erec-ki-gala, ousting her from her throne and sitting there in her stead. But retribution was swift and deadly:

“The Anuna, the seven judges, rendered their decision against her. They looked at her – it was the look of death. They spoke to her – it was the speech of anger. They shouted at her – it was the shout of heavy guilt. The afflicted woman was turned into a corpse. And the corpse was hung on a hook” (ETCSL 164-172).

Inana was kept in the Underworld by the stern judgment of these seven judges. And the judgment of two of her heavenly ‘fathers’, Enlil and Nanna, was equally severe:

“Inana craved the great heaven and the great below as well. The divine powers of the underworld are divine powers which should not be craved, for whoever gets them must remain in the underworld. Who, having got to that place, could expect to come up again?” (ECTSL 190-194).

In Ted’s poem, the repeated phrase “You had to strip off” reflects the repetitions of the Sumerian texts. Like Inana, the woman (and the brief biographical details given in the poem identify her with Assia) “had to go underground”, “go deeper”, gradually disrobing, being “forced to strip off”, elements of her life until her “last raiment”, “the sole remnant” of everything that might hold her to life was stripped away and only “the bed in the underworld” remained.

The woman in Ted’s poem is referred to only as ‘you’. She could be any woman, real or fictional, but Ted included biographical details which matched some of the most significant events in Assia’s life.

To Assia and her family, the “crossed lightnings” of the cross-shaped Nazi swastika6 symbolized everything about the Germany from which they escaped. So, symbolically, they were stripped off.

It was not Israel to which Assia’s family went, because Israel did not gain independence until May 1948, but to the British Protectorate of Palestine. Assia went to a school for well-off Arab children in the German enclave, and she left Palestine with a British soldier and was married to him in England in 1947. So, she stripped off Israel and the “cactus-hair” irritation, confinement, but also seemingly “bullet-proof” protection of Jewish family, culture and religion in a place which was to become, specifically, a home for Jews.

Assia’s father was of Russian descent, and he loved music, literature and the arts. It is likely that he taught Assia to love Pushkin’s work, but the romance, drama and satire of Pushkin’s writings clearly appealed to her in any case. She treasured a book of Pushkin’s poems, plays and prose which she inscribed with her married name, Assia Steele, in 1950, added the inscription Assia & David W. in 1956, and she kept it until her death7. Pushkin’s, Eugene Onegin, with its theme of romantic and ill-fated love, reflected Assia’s own life in some ways. Three times she had fallen in love and married. Three times these marriages ended in divorce. Her love affair with Ted, too, was romantic, compulsive, full of difficulties and ultimately ill-fated. The removal of ear-rings “worn in honour/ Of Eugene Onegin” (possibly the same leopard-claw ear rings, symbolic of Dionysian love, that are worn by the woman in ‘The Pan’ (BL 12, THCP 1120)), parallels the removal of Inana’s jewellery on her descent to the Underworld. The woman in Ted poem, however, was specifically stripping off “Russia”; and at the same time, perhaps, all allegiance to the romance and toils of human love.

In British Columbia, Assia had divorced her first husband and married again. Ted’s reference to the “fish-skin mock-up waterproof” with its “erotic motif / Of porcupine quills” may well describe something she wore, but its artificial nature, its “cannery” origin, its simulation of erectile porcupine quills, all suggest that this “waterproof” was, symbolically, a protective shield or mask which Assia eventually stripped off, just as she abandoned her marriage to Richard Lipsey when she fell in love with David Wevill. The painful quills, like the barbs and hurts associated with this brief marriage to Lipsey, however, were not so easily removed. They “pierced” her, “working deeper” and staying with her, just as love wounds always do.

“Finally”, all Assia’s masks, all her adopted Englishness, together with her three wedding rings, each signifying a new name and a new persona, had to be removed, just as Inana’s “golden ring was removed from her hand”. And, as in Inana’s descent, the next thing Assia loses as she goes deeper are her protective gems.

Inana had her lapis-lazuli measuring rod and measuring line taken from her. These were symbols of the divine powers of the “great heaven” and tools through which its gods measured and weighed out their judgment. Lapis-lazuli is also the stone of Venus, Goddess of Love. In Ted’s poem, the gemstones are rubies and emeralds, stones related to Mars and Venus, whose powers are combined on the Path of the Sword. But by connecting these gemstones with “Urim and Thumin”, which were part of the High Priest’s jewelled breastplate in the Hebrew Temple, Ted made a direct link with Sumerian and Babylonian mythology.

The Hebrew Priest’s breastplate was called “the breastplate of judgment” and Urim and Thumin are thought by Jewish scholars to be connected with the Tablets of Destiny which were held by the gods who wielded Truth and Justice in the Mesopotamian Creation myths. They are also believed to have been used by the Hebrews as a divine oracle - “the mysterious word of revelation”–and as “instruments through which Yhwh communicated His will to His chosen people”8.

In ‘Descent’, Urim and Thumin appear to symbolize the protection of the gods. But in the final extreme of Assia’s anguish, “cowardly / They scatter”, leaving her (like Inana) naked and unprotected, as the very last thing which might hold her to life, her daughter, is stripped from her. Her confusion, courage and determination pervade this poem. And throughout, the compulsion which drives her to go ever deeper, until nothing remains between her and “the bed / In the Underworld”, is caught in the phrase “you had to” (and once, “you were forced to”). She is driven on by her own demons, her own insecurities, and the conflicts caused by the masks and personae she has adopted in order to fit into the many foreign cultures in which she lived. Finally, the severe judgment of others, and her own severe judgment of herself, stripped away all masks, all protection, and, in its qlippothic excess, it was stronger than the natural instincts of love, which are heard in the poem in her “choked outcry”. So, with her “own hands”, she punished herself by taking her daughter’s life: nothing, then, was left to prevent her, or shield her, from death.

At the end of ‘Descent’, Ted makes explicit the parallel between the woman in the poem and Inana. But it is only Inana, with all her dangerous powers, who is left trapped “between strata / That can never be opened, except as a book”. Having resurrected her in his poem, and given her a part in Assia’s life and death, Ted had to ensure that Inana no longer existed in our world except as a Goddess about whom we may read in a book. So, acknowledging her by name, he used his poetic and Cabbalistic knowledge and skills to confine and control her, trapping her between the strata of his lines and, with his final words, decreeing the limits of her powers.

‘Folktale’ (C 6)

‘Folktale’ the sixth poem in Capriccio, occupies Sephira 6, Tiphereth (Beauty) at the very heart of the Sephirothic Tree. It also represents the broadest part of the steel Martian blade of the Cabbalist’s Sword, where the letters AGLA are etched into it with oil of VITRIOL (Sulphuric acid)9. Metaphorically, these attributes of the Sword represent the Divine guidance the Cabbalist seeks when wielding it and the dissolving, acidic powers associated with its use.

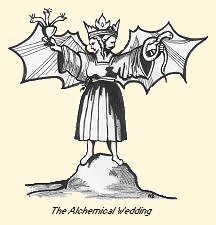

As benefits the energies of Tiphereth, which are balanced on the Pillar of Equilibrium, ‘Folktale’ sets out a seeming balance of desires between “He” and “She” (capitalized throughout the poem). Tiphereth is ruled by the Sun and here, in Cabbala and Alchemy, the male and female essences are exposed to the Sun’s burning light before being united in an alchemical ‘wedding’. Here, too, the vitriolic Sword must burn through the emotional matrix of the male/female relationship in order to clearly reveal whatever qlippothic energies lie at its heart. Because of the dangerous, vitriolic nature of this process, Ted needed to remain as rational and detached as possible, so his use of pronouns instead of names in this poem is especially appropriate.

At Tiphereth our Sun is a worldly reflection of the energies of the Source, but the male/female relationship of the couple at Tiphereth must be balanced and harmonious in order to burn with the true Beauty of Love. The qlippoth of Tiphereth is ‘Hollowness’, and the title of Ted’s poem, ‘Folktale’, suggests the distorted reflection of true Love which prevails in this poem.

“He” and “She” “ransacked each other” for “everything they lacked” and which they thought the other possessed. The unreality of their perceptions of each other is emphasized in the first two lines of the poem. “He” clearly did not know the truth behind her seeming boldness: did not see, behind the mask she presented to the world, the fragile being who had “risen”, phoenix-like, “out of the cinders”. “She”, from the very beginning, confidently “knew he had nothing”.

As in the Crow poem, ‘Lovesong’, “He” wanted “her whole past and future” (‘Lovesong’ C 88, THCP 225). He wanted (in ‘Folktale’) the Dionysian “leopard Ein-Gedi” that she might have brought from Palestine; tokens of her Russian ancestry; German “gutturals” made musical by her Arabic schooling; the mystical and magical hints of “Cabala” and “the ghetto demon” history of her Hebrew and Jewish people. “He wanted the seven treasures of Asia”, which are the inner powers of faith, perseverance, a sense of shame, avoidance of wrongdoing, mindfulness, concentration and wisdom, but all he actually sought were the inherited, worldly treasures of skin, eyes, lips, blood, hair and ancestry. And, at the same time, he wanted a “mother” of sweetness and comfort.

The ‘She’, in ‘Lovepet’, wanted “him safe inside her / Safe and sure for ever and ever”. In ‘Folktale’, “She” wanted the thrill and danger of a liaison with “a runaway slave” (whether the slavery is to her or to someone else, or both, is left uncertain) but she also wanted the fairytale romance of an “Eden-cool” “love-knot” with only a fairytale “child of acorn” to share it. She wanted “escape without a passport” – an unauthorized transgression of boundaries, but also the “heraldic” symbolism and status of his Englishness. And she wanted, the “shades” of his fiery “broken-armed” love of Sylvia – the cool shadows of it but not the full, dangerous burning force of it.

Ultimately, both wanted to begin their lives again. She wanted “the hill stream’s tabula rasa” to wash away her past. He wanted to find the “thread end of himself” so that he could begin to untangle the muddle his life was in.So, and the phrase is repeated at the beginning and end of the poem to emphasize the divisive, destructive, warring nature of this pillaging, “they ransacked each other”. But everything they wanted “could not be found”: Not in themselves, nor in the other. And the hollowness with which they began, and which they encountered as they struggled is clear in the final lines of the poem. Fingers, which at Tiphereth should have been entwined in peaceful harmony, instead, at their darkest moment “when midnight struck” were still wrestling in the “flames” and “crackling thorns” of “everything they lacked”.

Finally, in Cabbalistic terms and in true folktale tradition, there is a moral to this story. The Cabbalist’s work, at all times, is guided by the maxim ‘By equilibrium and self-sacrifice is the gate’. But in ‘Folktale, as the heart of the relationship is revealed, it is apparent that even when it was most necessary, this couple failed to see beyond their own wants, their own problems, and their own perception of the other. They failed to look deeper and to see each other in a more selfless and accepting way. Ultimately, when the witching hour of midnight struck and the dark energies were at their most disruptive, they still had not learned to balance eros and agape in their love. So, their relationship was doomed.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

1. Scholem, G. On the Kabbalah and its Symbolism, Schoken Books, N.Y., 1960. pp. 110-112.

2. This is found in the alchemical and mystical writings of Jacob Bohme (1575-1624) who called the polar forces of systole-diastole ‘divine wrath’ and ‘divine love’– ‘the yes and no in all’; and in the work of other Alchemists, Cabbalists and Rosicrucian’s.

3. Myers, L. Crow Steered Bergs Appeared, Proctor’s Hall Press, Tennessee, 2001. p.79.

4. This myth had particular relevance for Ted. Roy Davids, whose help and friendship Ted acknowledged in the Foreword, comments that “the book is as much about Ted Hughes as it is about Shakespeare”, and that Ted had “considered putting the whole Plath story on the stage of this book – behind the scenes even – using it as a metaphorical ground rather than writing Birthday Letters” (Appreciation of Shakespeare and the Goddess of Complete Being, under ‘Articles’ menu at https://www.roydavids.com/).

5. There are translations of these Sumerian myths in the Ted Hughes’ Library archive at Emory University, Atlanta, USA. All my quotations are from the beautifully translated version of Inana’s Descent to the Nether World to be found in The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature (ETCSL) of the Faculty of Oriental Studies at the University of Oxford at https://www-etcsl.orient.ox.ac.uk./ This translation spells her name ‘Inana’, but Inanna (which Ted uses) is also common.

6. This ‘Thunder Cross’ was the symbol of the Prussian God, Percunis, God of thunder, fertility, law and order. It was adopted by Adolf Hitler as a symbol for the Third Reich before World War II.

7. This book is now in the Ted Hughes’s Library archive at Emory University in Atlanta.

8. The Jewish Encyclopedia.com at https://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/view.jsp?artid=52&letter=U .

9. In Cabbala, a Notarikon is a word made up from the letters of a phrase which it is designed to represent. AGLA is a Notarikon which represents “Ateh, Gibor, Leolam, and Adonai” : “To thee be the Power unto the Ages, o my Lord”. VITRIOL (widely used in Alchemical manuscripts) is a Notarikon for “Visita Interiora Terrae Rectificando Invenies”: “By investigating everything and bringing it into proportion you will find the hidden Stone”. Of VITRIOL, Crowley noted: “As an acid eats into steel… . so am I unto the Spirit of Man” (Crowley. Liber LXV, I, 16).

Poetry and Magic 3: Capriccio 2 text and illustrations.

© Ann Skea 2007. For permission to quote any part of this document

contact Dr Ann Skea at ann@skea.com