In the Tarot journey, after ‘the dark night of the Soul’ and the card of Death, comes the release and subsequent tempering of the Spirit. The three necessary parts of the human journey – the progressive development of Body, Soul and Spirit - can be seen particularly clearly in an alternative layout of the Tarot cards which consist of three lines of seven cards1

‘Ariel’ (dated 27 Oct. 1962), which is the next poem in Plath’s sequence was written more than three weeks after ‘The Detective’ and it would be aligned with the card of Temperance in the Tarot journey.

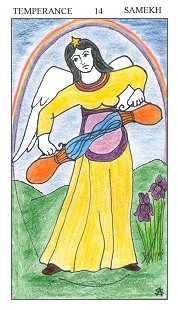

The meanings traditionally given to this card are of the mingling of all elements, harmony, balance, self–control and the completion of a journey. All these meanings are also attributed to the card of The Chariot and the card of The World which lie above and below it respectively in the 3/7 layout.

‘Ariel’ which was titled ‘The Horse’ when it was first published is, according to Plath’s note2 and to that of Ted Hughes in the Collected Poems3, about a ride on a horse called ‘Ariel’ of which Plath was “especially fond”4.

Elsewhere5, Ted Hughes says that the poem “describes and almost apotheosizes a dawn ride, on Dartmoor”. He describes the poem as “the quintessential Plath Ariel poem in that the speaker, the I, hurls herself free from all earthly confinements and aims herself and her horse – as the poems says, ‘suicidal’ directly into the red, rising sun”. And he notes the “overt sense” of “liberation from earthly restraints (earthly life)… rebirth into something greater and more glorious… – a spiritual rebirth perhaps”.

In this sense, the poem is exactly right for the card of Temperance. It also conveys a sense of the presence of “something else”, which “hauls” the speaker free of the earth – free of “hooks”, “shadows” and “dead hands, dead stringencies”. That inexplicable “something else” is present on the card in the magically suspended stream of water which flows continuously between pitchers held in either hand of an angelic figure. That “something else” may be poetic inspiration. And it may be Mercurial or Angelic assistance, since the figure on the card is traditionally identified as the Rainbow Goddess, Iris, who, like Mercury, is messenger of the gods, but who may also be identified as Ariel, the Angelic Prince who, in magic, has dominion over the elements and the creative forces.

Rákóczi writes that heretical sects taught that this stage of the journey represents “the transmutation of the base and corrupt into the noble and whole that had to be achieved through actual experience”6.

Plath was certainly writing from actual experience, although her own precipitous gallop was on the runaway horse, Sam, when she was at Cambridge a few years earlier7. Her poem moves from stasis to flight, from the “stringencies” of death and corruption to the purity of air and spirit. It combines the four elements - earth (in tor and furrow), air (in the flight of the arrow), water (in the dew and the seas) and fire (the sun). And the speaker’s balance and control of the horse, like Plath’s control of the poem, is precarious but sure. This is a superb evocation of a precipitous ride full of “striving ecstatic energy”8 but it is hardly temperate, in the usual meaning of the word.

Yet, the so-called ‘The Flight of the Arrow’, in Crowley’s Golden Dawn teachings, is associated with this card and is not only seen as “the mingling of contradictory elements in a cauldron”, which finds an echo in Plath’s sun, which is the “cauldron of morning”, but the arrow itself is described as “a symbol of directed Will”. Plath’s speaker, the ‘I’ of the poem, becomes the arrow, and it is her Will which makes her one with God’s lioness and which propels her suicidal “drive” into that cauldron9.

If Plath did use the card of Temperance as inspiration for ‘Ariel’, the intemperate, “suicidal” ending of the poem is not appropriate, for there is still more for the initiate to learn before the final state of harmony in The World (card 21) is reached. The newborn spirit has to be tempered, subjected to ordeal by fire and water, just as swords and knives are tempered to give them strength and flexibility. But this is not what happens in ‘Ariel’ and, in occult terms, Plath was attempting union with the energies of the Source in this poem, before she was fully prepared.

Ted Hughes, writing of the drafts of Plath’s ‘Sheep in Fog’, pointed out that this poem too, describes a horse–ride and that there are reflections of ‘Ariel’ in it, but he also pointed to Plath’s deleted lines in which “Ribs, spokes, a scrapped chariot” and “I am a scrapped chariot”, suggest the crashed chariot of “Phaeton, son of a mortal woman and Apollo (the god of the Sun and of Poetry)”. Extrapolation on these images and others, Hughes suggested that Plath sought to retain the “fierce inspiration and confidence” which had produced the Ariel poems, but that this “astonishing, sustained, soaring defiance”, this “drive” like her speaker in ‘Ariel’ “straight into God’s eye” had ultimately failed.

Years later, Hughes wrote that Plath’s real creation in the Ariel poems was “the inner gestation and eventual birth of a new self-conquering self”; and that this was “the most important task a human being can undertake (and surely the most difficult)”. But he wrote, too, that “this new self, who could do so much, could not ultimately save her”, and, in a letter to Keith Sagar in 1981, he referred to Jung’s view that the moment of achieving such a rebirth was the most dangerous moment, when the person was most vulnerable10.

In ‘Ariel’, Plath was perhaps undertaking that dangerous ‘suicidal’ flight too soon after her rebirth. But, of course, if Plath was using the Tarot as a healing journey then ‘Ariel’ was not the final poem of that journey or of her Ariel sequence.

The next poem in the sequence, ‘Death & Co.’ (dated 12-14 Nov. 1961) was written just over two weeks later, but ten other Ariel poems had been written during that time.

On the typed duplicate of Plath’s contents page the handwritten title ‘Death & Co.’ has been inserted between ‘Ariel’ and ‘The Magi’ and it has been typed onto the original title page with the same insertion indicated by an arrow11. Whether Plath was simply correcting an omission on these pages of whether these insertions indicate that the poem itself was also inserted amongst the manuscripts at a later date, it is impossible to tell.

If both title and poem were inserted, then the alignment of each of the poems with a particular Tarot card from this point on would change.

I will assume, for the moment, that only the title was inserted and that ‘Death & Co.’ was inspired by or written for the card of The Devil (card 15) which follows the Temperance card in the Tarot sequence, although the poem seems, initially, to have little to relate it to this card or to its position in the Tarot journey.

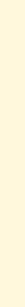

The Devil represents the amoral, genderless, supremely powerful creative force – Pan Pangenitor, the all–begetter. It is shown in the traditional Tarot de Marseille deck and in The Painted Caravan, as a horned, goat–legged, bat–winged creature, and loosely tethered to the altar on which it squats are two similar but smaller and wingless beings. In some Tarot decks, these creatures are human – one male and one female – but always they share some of the Devil’s animal attributes; and always their demeanor is unconcerned, or even happy.

The symbolism of this imagery suggests that we are the offspring of this Devil – that we share some of its energies and that we are subject to its power. But the details of the image suggests also that either we are unknowingly enslaved, or we know of the bonds which bind us and choose to accept them, for the looseness of the bonds shows that we can throw them off.

Pan’s energies are lustful, vital, Mercurial energies. They are capricious and have no foresight or scruple. Allowed free reign, they have the power to transcend all limitations and cause chaos and destruction. But they are also the energies of the light–bearer, Lucifer. And without them we are sterile.

The sexual energies are, of course, one expression of the Pan’s generative powers and they are the cause of two kinds of bonds which may bind us. In excess and uncontrolled they can threaten the individual and society, but excessive suppression, either by personal inhibition or by Puritanical laws, can be equally destructive. The initiates’ task is to learn to control and use this creative spirit. Only then can they free themselves of the bonds of excess or suppression which tether them to the altar of The Devil.

Sexual energies, however, are not the only creative energies. Plath, whose whole concern in Ariel was to free the creative energies which inspired her, seems, in ‘Death & Co.’, to have intuited a poetic meaning to this card. ‘Thalidomide’, ‘Barren Woman’ and, in particular, her earlier poem ‘Stillborn’ (June/July 1960) offer a clue: Plath’s poems are her babies, without inspiration she is barren; influenced by the wrong energies, they may be deformed; without spirit, they are dead.

Plath’s explanation of the poem was seemingly ingenuous and frank. She described it as being “about the double or schizophrenic nature of death – the marmorial coldness of Blake’s death mask, say, hand in glove with the fearsome softness of worms, water, the other katabolists. I imagine these two aspects of death as two men, two business friends, who have come to call”12.

There are many ways in which a poem might die. But in ‘Death & Co.’ there are two – “of course there are two”.

One is “marmorial”, restrained, cold and precise, like a death mask. Like a Classical Greek poem and like the poems in ‘Stillborn’, such poems are “proper in shape and number and every part”, but “they are dead”. They may be carefully composed and shaped, laid out like “sweet babies” in “a hospital icebox” but their “flutings” (like tunes from Pan’s pipes, which are held in a Fool’s hand on The Painted Caravan’s image of The Devil) are those of their “Ionian/ Death–gowns”, as if their music is constrained by these Greek garments in which they are clothed. And the two little feet of the babies in Plath’s poem perhaps reflect the two feet of Classical Ionian poetry.

The other poetic death which Plath describes is that of the “long and plausive” poem, the poem written to please; the poem in which the poet is “masturbating a glitter” because he or she “wants to be loved”. Plath’s reference to the natural “katabolists” – “worms” and “water” – suggests nature poetry, but she associates it with a long–haired, obsequious “bastard” who is artificially stimulating, “masturbating”, and wasting his natural creative energies.

The speaker in the poem is threatened by both forms of death but is “not his yet” and “does not stir” (a phrase which can mean both ‘does not move’ and ‘is not moved’). And Plath ends the poem with a magical ritual in which she makes from the “frost” of the first kind of death “a flower”, and from the “dew” of the second “a star”: both of which are images of generation and hope. She also ensures that the dead bell tolls twice – not for her, but for “ Somebody” or, perhaps, for the two somebodies – “ two business friends” whose business was to entice and devour her.

Poetic death, like actual physical death, destroys the creative Spirit. In ‘Death & Co.’, Blake’s death mask has eyes which are “lidded/ And balled”. He no longer has the spiritual vision which allowed him to free himself from the bonds of social conventions and religious dogma enough to proclaim that “The lust of the goat is the bounty of God”13, or to imagine the “immense world of delight” which is “closed” by our “senses five”14.

In Plath’s poem, however, her creative Spirit remains alive and free, and she expresses that creativity and freedom in her ‘Ariel’ voice.

The next poem, ‘Magi’ (undated but inserted between poems of the 16 and 17 Oct. 1960), however, is colder and full of abstracts. With its references to “The Good, and True”, “Evil” and “Love” (note the capitals), Plath’s “dull angels” are from the world of Plato and his Ideas: the world of Greek Socratic rationalism and objectivity from which Ionian poetry emerged and from which intuition and imagination, which nourish the creative spirit, were excluded.

Clearly such abstracts would threaten the new–born Ariel spirit, just as the “ethereal blanks” of these angelic beings’ “face-ovals” hover “Loveless as the multiplication table” around the six–month–old child in the poem.

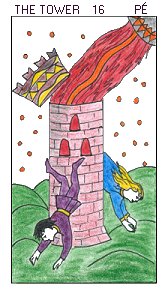

The Tarot card which is associated with this poem is The Tower (card 16). It depicts two figures falling to earth from the top of a lightning–struck, castellated tower, whilst hail or brimstone fall all around. Its usual divinatory meaning is catastrophe, sudden dramatic change, or revolution. At a deeper level, it can also symbolize the dramatic overturning of long–established beliefs as a result of new insight, and ‘the rending of the veil’ which reveals mystical knowledge and new spiritual and mystical awareness.

‘Magi’ has none of the dynamic power of the poems which Plath was writing in October and November 1962. Its whole tone is one of calm confidence and strength. It is impersonal and philosophical, quite unlike the dramatic energies depicted on The Tower card, although it does deal, in its own way, with part of the card’s meaning.

The dismissal of abstract, rationality in favour of nature and natural instincts is clear as Plath pits the strong physical presence of the child, secure on “all fours” and trusting its own instincts and feelings (nature not “theory”), against the “papery godfolk”. These “dull-angels” are not the ‘noble beings’ or ‘magicians’ which give the word ‘magi’ its meaning. They may be “the real thing, all right”, as the speaker says, but their gifts, “Salutary and pure” as they are, are deemed unacceptable here, their “whiteness” is compared unfavourably with “laundry” and their Love with mathematical tables. Finally, they are sarcastically sent off to the crib of “some lamp-headed Plato” who will better appreciate their “merit”, so that the speaker’s “girl” may flourish.

There is no suggestion in the poem of The Tower’s connection with the lightning strike of divine inspiration or of any new mystical awareness. The title of the poem does call to mind the Magi – the three Kings – of the Christian nativity story, in which case, the child in the poem would be a symbol of divine, spiritual blessing and renewal. The emphasis in the poem, however, is on the banishing of these magi and their ‘gifts’ so that the child’s natural Spirit may flourish.

Ironically, Plath did not let her own Spirit have free rein in this poem: there is no catastrophic overthrow, no dramatic upheaval as there is in The Tower. Instead, she achieved the stripping away of a rational system of beliefs in a poem which is, itself, precise and purely rational. Nevertheless, the poem is about freeing the Spirit of a recently born child and, as such, it makes an appropriate choice for this stage of the Tarot journey.

The next poem, ‘Lesbos’ (dated 18 Oct. 1962), however, seems to have no obvious connection with the tempering of the Spirit. It was written before ‘Ariel’ and immediately after ‘Daddy’, ‘Medusa’ and ‘The Jailor’, all of which deal in a realistic way with people and events, rather than with anything abstract or mystical, and it shares the malign, vindictive energies which are apparent in these poems. Frieda Hughes cites ‘Lesbos’ as an example of one of her mother’s more ferocious and “lacerating poems”; one which her father left out of the British edition of Ariel, because “the couple so wickedly depicted” lived in Cornwall and would have been “much offended by its publication”15. As she has rightly said, ‘Lesbos’ “reads out loud in such a way that the energy gathers into a sort of whirlwind fist”16.

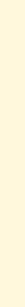

How, then, can this poem represent The Star (card 17), which is the next card on the Tarot journey and which, traditionally, is interpreted as the most beautiful, visionary card in the deck?

The Star means hope, intuition and inspiration, and it presages the end of the initiate’s journey and the attainment of wholeness. In some traditions, this card always has positive meaning, whatever its orientation17. And in traditions where a reversed meaning is given to the card when it is upside–down, this reversed orientation indicates misfortune, self–doubt, an unwillingness to accept one’s intuitions and, even, the misuse of psychic powers. None of this is apparent in ‘Lesbos’.

On The Star, a beautiful, naked woman kneels beside a pool into which she pours water from two pitchers. Above her head is a brilliant, eight–pointed star, which identifies her with Venus/Aphrodite, and also with the more ancient goddesses, Astarte and Innana. All these goddesses, are goddesses of love but also, in their darkest forms, they are know as ‘Goddess of War’, ‘The Hag’, and ‘Death Goddess’. With more stars falling around her, the woman kneels on the earth, demonstrating the goddess’s presence in the world, and she rests one foot in waters which are identified as the Waters of Life and the dark, chaotic, Bitter Sea of the unconscious.

To encounter this double–natured Love Goddess thus, is both awe–inspiring and dangerous, and to bear the full, unveiled force of her energies requires both courage and skill. She may enthrall and inspire, but she may also seduce and entrance with her deathly powers. She is both hunter and hunted, and her animals, lion, tiger, panther, all the cats, share her hunting skills.

Strange as it may seem, given the unpleasantness of the poem, ‘Lesbos’ is about love, and about the worldly distortions of love. Plath’s title, refers to the island on which the Ancient Greek, lyrical love–poet, Sappho was born. And Plath admired Sappho, listing her first among the few poets she considered to be her own historical rivals for fame18. Sappho wrote poems to Venus, to Aprodite and to the moon; she composed a lament for Adonis; a song for a wedding; and she wrote many love poems addressed to women.

Plath’s poem is addressed to a woman, but it is far from loving. And the only way this poem could be made to fit the meaning of The Star and this particular stage of the Tarot journey, is to suggest that Plath was rejecting the worldly aspects of love (the dark side of Venus/Astarte which is represented in the poem by the blood-soaked moon) in order to free her Spirit of the dark things which she saw reflected in herself. As Alaister Crowley wrote, “There are love and love. There is the dove, and there is the serpent”19. Under The Star, the initiate must tame (but not kill) the serpent in order to release the dove.

There is genuine love: And there is the Hollywood romance – theatrical, artificial and full of false drama, envy, jealousy, hate discrimination, demands, lies, loveless sex and moonshine. Like the “I” and the “You” in Plath’s poem, they are “two venomous opposites”, but both can exist within a single person.

Plath’s speaker describes all the things associated with “Hollywood” love. Her cinematic imagery of a “windowless” place, flickering “fluorescent” light, “coy” unrealistic papery scenery, “a widow’s frizz” of artificially curled hair, an “unstrung puppet” of a child who is dramatically “schizophrenic” with panic, and a narrator who is “a pathological liar”, all convey falsity and pretence.

The “You” of the poem has “blown her tubes”, which suggests she has used artificial means to deal with fertility problems; she has blocked the natural love of the child for her kittens; she can’t stand girls, favours boys, and she maligns her husband’s sexuality and blames a stereotype “Jew-mama” for this. All her love is un–natural and distorted. And, although it is unclear whether it is she or “I” who believes that the speaker should “have an affair” or sit, like a mermaid or a Siren, on a Cornish rock combing her hair, the “tiger pants”, like the child’s kittens in their “cement well”, suggest the mistreatment of the predatory cats which belong to Venus/Astarte.

Perhaps “in another life”, or “in air”, these two aspects of love – the “Me” and the “You” – could become healthy and whole, but “Meanwhile”, in this life, “doped” by the latest soporifics, befogged by everyday chores, they remain separate and opposed. “I” calls “you” “Orphan”, as if trying to cut off this personality which is made sick by the natural world and for whom the “thrill” of “acting, acting, acting” has passed. She sees the “impotent husband” as potential protection from the “lightning” and the “acid baths” of “you”: like the transmission pole of an old trolley–bus (tram) or the opposite pole of a magnet, he might neutralize or channel her dangerous energies, so she tries to “keep him in”. But he, “flogged” (beaten, worn-out), “lumps it” (a wonderfully vivid phrase for a disgruntled, slumped, stomping exit) down and artifical, “plastic” cobbled hill. And all that the “I” sees are the “blue sparks”, like the sparks from a faulty electrical contact, which “spill” and split like shattered quartz crystal.

Quartz is a magical crystal, a symbol of integrity and virtue and attributed with special protective and psychic powers. But the crystal is shattered, Plath’s speaker exclaims “O jewel. O valuable.” but she immediately recalls a bloody moon, like a “sick /Animal”. The dark, moon–face of the Goddess has appeared and even as her moon returns to normal it remains terrifying, “Hard and apart and white”, as if the Goddess, herself, has been injured. Even her light on the sand is a “scale–sheen”, serpentine, and terrifying, and her double nature is reflected in the “mulatto” bodies which “We” (the you and the I are remembered as united in this task) had lovingly shaped from that sand, as if attempting to re–combine, with love, the “million bits” of quartz (which is what sand is) until it feels like “silky grits” in one whole but two–natured body.

This hallucinatory, dream–like vision ends with the equally dream like image of a dog carrying off the husband. Dogs, too, have a long mythological association with the Goddess. They howl at the moon, so became a symbol of the Moon Goddess but they are also associated with fertility20. The dog in ‘Lesbos’ is part of the moonscape, and the husband, everywhere in the poem, is a useless, “doggy” companion - “an old pole”, “hugging his ball and chain down by the gate”. Perhaps the Moon Goddess sent a dog to retrieve him and punish him for his incompetence and weakness. But for whatever reason he is in this poem, he is not wanted by either of the women and, if this poem is about cleansing and freeing the Spirit of Love, he is part of the worldly manifestations of love from which the speaker is freeing herself.

That memory/dream, however, was then: “Now”, the speaker is “up to her neck” in “hate”. Whether this hate is hers or she has been filled with it by the 'you' of the poem is unclear, but the speaker is packing away all the things which promise new life – the uncooked “hard potatoes”, the “babies“, the “cats“ ready to take them with her.

The doubleness continues in lines in which “acid” is linked with “love”, “love” with “hate”; “white and black”; the sea “drives in” and is spewed back; and the slumped husband and the hate–filled wife who (inexplicably) fills him daily with “soul–stuff”. The final images of “you” are of a “flapping and sucking, blood-loving bat” whose voice is so close to the speaker that she wears it like an ear–ring. “That is that”, repeated twice, has a double finality.

“You” peers from the door: “I” can’t communicate but, ultimately, Plath closes that door and the speaker watches all the artificiality, all the trappings which hide sick love and destructive hate – all that “cute décor” and “you” disappear. The images which Plath chose to describe this closing are images drawn from nature: it is like “the fist of a baby”, or, more appropriately, like a sea–anemone, which, when touched, enfolds its beautiful but deadly tentacles within a smooth, rubbery body.

The speaker, “still raw” (sensitive, sore, and possibly now stripped of all artificialities) say “I may be back”, but it is not clear who says the line which directly follows this. Is it the speaker making a statement about the familiarity of “you” with “lies” – “you know what lies are for”? Or is she pointing out that her own promise to return is a lie? Is this another suggestion that I and the you of the poem are the same person and that the whole ordeal is a deliberate cleansing of the Spirit of love in that person?

And are we to accept the final line as a declaration that the two aspects of love, the spiritual and the mundane, will never meet again? Or is the “Zen heaven” which the you of the poem espouses another of her artificialities, and meeting is possible only in a dogma–free state of mystical knowledge?

In the end, the poem confirms none of these speculations. If Plath did have a purpose for this poem other than to recreate and ‘dismember’21 some friends or acquaintances and to vent her feelings in her Ariel voice, we may never know.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

1. The numbers 3 and 7 both have ancient religious, mystical and magical importance (e.g. in Christian religion, the Trinity and the seven days of the Creation).

2. Plath’s note for a BBC script. Ariel: The Restored Edition, p.196.

3. Sylvia Plath Collected Poems, Note 194, p 294.

4. Surprisingly, given the energy of the poem, Anne Stevenson in Bitter Fame (p. 272), notes that this horse was “an elderly, ponderous horse”.

5. Hughes, T. ‘The Evolution of ‘Sheep in Fog’, Winter Pollen, p.199.

6. Rákóczi, The Painted Caravan, p.54.

7. Plath records this ride vividly in ‘Whiteness I Remember’ (Sylvia Plath: Collected Poems, pp.102-3). Ted Hughes’ poem ‘Sam’ also describes it (Birthday Letters, Faber, 1998, pp.10-11).

8. Hughes, Winter Pollen, p.200.

9. Crowley, A. The Book of Thoth, Samuel Weiser Inc. York Beach, Maine, 1985, pp.103-4. There is no evidence that Plath read Crowley’s work, most of which was only available in libraries until The Book of Thoth and the cards described in it were published in a trade edition in 1985. However, much of Crowley’s teaching was repeated in more easily available books of occult lore.

10. Hughes to Sagar, 23 May 1981, in Reid, C. (ed.), Letters of Ted Hughes, p.446.

11. Brain, T. ‘Unstable Manuscripts’, in Helle, A. (ed.), The Unravelling Archive, p.18.

12. Plath, Ariel: The Restored Edition, p.196-7. In Sylvia Plath: Collected Poems, Ted Hughes adds that “the actual occasion was a visit by two well–meaning men who invited TH to live abroad at a tempting salary, and whom she therefore resented”. Neither explanation rules out the possibility of another, occult, meaning to the poem.

13. ‘Proverbs of Hell’, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, in Plowman, M (ed.) William Blake: Poems and Prophecies, Dent, London, 1970, p.45.

14. William Blake. “ How do you know but that ev’ry Bird that cuts the airy way, Is an immense world of delight, closed by our senses five?” . ‘A Memorable Fancy’, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, In Plowman, M (ed.),William Blake: Poems and Prophecies, p.44.

15. Hughes, F. Interviewed in Ariel: The Restored Edition, p.6. She went on to say that she “remembered being driven around in a car full of cats and my little brother” and that she identified with the references in the poem.

16. Hughes, F. ‘Foreword’ to Ariel: The Restored Edition, pp.xv-xvi.

17. Huson, P. The Devil’s Picture Book, Abacus, 1972. p.228.

18. Plath’s journal entry for 29 March 1958, in Kukil, K.(ed.), Journals of Sylvia Plath, p.360.

19. Crowley, A. The Book of Thoth, p.108.

20. Generally, dogs do the goddesses’ bidding, as did the dogs which devoured Acteon after he encountered the virgin huntress, Diana, bathing. Hecate/ Diana (before Diana became known as the Virgin Huntress) was a night–huntress accompanied by a pack of demon dogs. She was also, in one of her Roman forms, a goddess of fertility.

21. Frieda Hughes wrote of “the extreme ferocity with which some of [her] mother’s poems dismembered those close to her…even neighbours and acquaintances. ‘Foreword’, Ariel: The Restored Edition. pp.xvii-xviii.