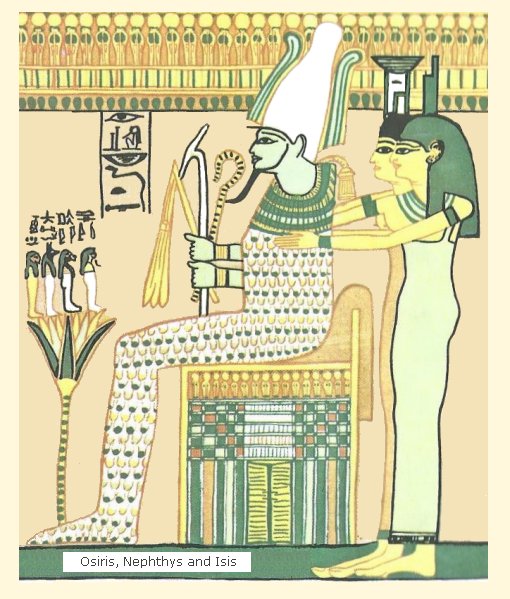

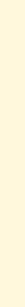

In the papyri which depict the Egyptian Hall of Judgment, the two share a place of importance immediately behind the seated Osiris, and Nephthys stands, like a shadow, alongside but partly hidden by, her twin.

In the papyri which depict the Egyptian Hall of Judgment, the two share a place of importance immediately behind the seated Osiris, and Nephthys stands, like a shadow, alongside but partly hidden by, her twin.

‘The Other’ (dated 2 July 1962), which is the next poem in Plath’s Ariel sequence, is aligned with the Tarot card of The Moon (card 18).

In Ted Hughes’ discussion of Plath’s journals, he writes of her confronting ‘The Other’. He was not at that time referring to Plath’s poem but to her other self –“ the deathly woman at the heart of everything”1 – that part of herself which, through her writing, she constantly strove to come to terms with and overcome.

Hughes describes her as confronting “her own moon–faced sarcophagus…the moon in its most sinister aspect”, and he writes that it was this ‘other’ which she closed in on as she developed her Ariel voice. By December, he wrote, “she knew quite well what she had brought off in October and November…she had overcome, by a stunning display of power the bogies of her life”2.

Plath’s journals, her reading of Jung, her honours thesis ‘The Magic Mirror’, and the imagery in many of her poems, confirm her interest in doubles, doppelgangers and mirrors. In ‘Mirror’ (dated 23 October 1961), a woman bends over the glass “searching…for what she really is” and in Plath’s journals, there are times when she speaks of herself in the third person: “I thought about the shock treatment description last night, the deadly sleep of her madness” or, in the next paragraph, of a judgmental alter–ego, “the blonde one, pure and smug and favoured”3.

There is a great deal of doubleness in Path’s poem, ‘The Other’. It is written in couplets and divided into two sections by a space between stanzas eight and nine. As in ‘Lesbos’, it is addressed to “you” by “I”. Yet, there is often confusion as to which is the grammatical subject of Plath’s sentences. And, towards the end of the poem, the lines “cold glass, how you insert yourself / Between myself and myself”, suggest that the speaker is confronting her own image in a mirror.

The you and the I of the poem are connected in other ways, too: “your head on my wall”, is linked in a single couplet with the “Navel cords” which, in the continued sentence, “Shriek from my belly”. This suggests that they are connected by birth and that the two subjects (indicated by the punctuation of these line) are aspects of the same being.

The “moon–glow”, the “sick one”, and all the grievous faults which follow in the next six lines (21-26), are attributed to neither “you” nor “I”, so, may apply to both; and these lines also link the “I” who rides the navel cords (line 18) with the mirror image of “myself and myself” (line 27).

Nor is the one who scratches identified in the lines which follow it as separate from the one who bleeds. Instead, the “cat”, is placed in a single couplet in such a way that its scratch and the subsequent blood-flow may be “Between myself and myself”.

None of this explains the first part of the poem, but the identification of “you” with “White Nike” whose “blue lightning” streams between the walls; the “moon–glow” and the “sick one”; the nightmarish imagery of “meathooks”, “corpuscles” and “blood”; the bad and “sulphurous” smells; the barrenness and the adulteries; the knitting which hooks “itself to itself”; the severed head and the “I” riding like a witch on the shrieking navel cords; all these have strong connections with lunar madness and with the dark face of the Moon Goddess.

All this, too, has strong connections with the Tarot card of The Moon, which depicts a moon which, ambiguously, may be seen as waxing or waning, full and dark. Dew–like drops fall to earth around it and two dogs (wolves or jackals) raise their muzzles to howl at it. Two towers (sometimes one black and one white) stand on the horizon and in a large pool in the foreground a clawed creature (crayfish, lobster or crab) raises its two fierce claws towards it.

Everything associated with the moon is symbolized on this card and in Plath’s poem. Its changing aspects; its influence on the waters of the earth: its connection with blood and with the monthly cycles associate with menstruation, fertility and birth; its connection with imagination, love and lunacy; and the black–and–white moonscapes in which dogs howl, dreams and nightmares flourish, and where witches ride their broomsticks and ‘draw down the moon’ into water, glass and magic mirrors in order to weave their spells.

Rákóczi writes that at this stage the initiate is “thrown into a trance” in which “the pageantry of rite and sacrifice are projected into his mind”. Through this process, the power of hallucination is demonstrated and the initiate is made “free from illusion and disillusion”. He mentions the association of Isis with the moon and interprets the falling dewdrops as her “pearls of wisdom”. The towers, he describes as “structures of the mind, as the beasts are of the body”; and the moon is “the initiation which is beyond either”4.

However, if Plath was writing ‘The Other’ with the Tarot card of The Moon in mind, then she did not follow Rákóczi’s guidance but chose a different mythological figure for her poem, and one which was far more appropriate for her purpose.

Plath names her Moon Goddess, Nike, just as she did in the earlier Ariel poem ‘Barren Woman’. Nike, in Greek mythology was ‘Victory’, and her name is sharp and abrupt and appropriate to the rhythms and tone of ‘The Other’. But Nike’s earlier, Egyptian, form is that of the Moon Goddess, Nephthys (which means ‘Lady of the House’5) and it is she whom Plath describes in this poem. A “doorstep”, and the “walls” between which this Goddess’s energies stream, flashing blue lightning, may represent her house; and her handbag and knitting her domesticity, but as Lady of the Body, she may also be the other self of the speaker, just as Nephthys is the secret, shadow twin of Isis.

Egyptologist Wallis Budge writes that whereas Isis represents the bright face of the moon, Nephthys is “the personification of darkness and all that belongs to it” including “death, decay, diminution and immobility”6

. But both Isis and Nephthys were “necessary to the coming into existence of life” and together these twins reassemble (knit together) and prepare the body of their brother, Osiris, for resurrection7.

Together, they prepare the funeral bed for Osiris, and Nephthys “kneels at the head of the bier and helps him to arise”8. Like her sister, Isis, Nephthys is “a mighty one of words of power”, and it is the words of both these goddesses, chanted over the bier, which help the deceased to be reborn.  In the papyri which depict the Egyptian Hall of Judgment, the two share a place of importance immediately behind the seated Osiris, and Nephthys stands, like a shadow, alongside but partly hidden by, her twin.

In the papyri which depict the Egyptian Hall of Judgment, the two share a place of importance immediately behind the seated Osiris, and Nephthys stands, like a shadow, alongside but partly hidden by, her twin.

Budge quotes the Greek historian Plutarch (c. 46–120 AD), who described Nephthys as “at first barren” (just as Plath’s ‘Other’ has “a womb of marble”), but as later having given birth to the Jackal–headed god Anubis, God of the Dead. And he wrote that the sistrum (the musical instrument which is the symbol of both Nephthys and Isis) was carved with “the effigies of a cat with a human visage” and had, on its lower edge, engravings of “on the one side the face of Isis, and on the other that of Nephthys”. He also wrote that “the Cat denotes the moon”.

The words of Isis and Nephthys were “Lamentations”, followed by “Festive Songs”. Plath’s words created a poem describing secrets, corruption and dismemberment, but in it the cut and the blood (which, in Rákóczi’s commentary on the card, presage the ultimate achievement of mystic knowledge and wisdom) are delivered by a “scratch” like that from one of the Goddesses’ cats. And the blood which is drawn, as in the cutting of a Gypsy initiate and in the dismemberment of Osiris, is “dark fruit”, “a cosmetic”: a wound which is necessary but “No, It is not fatal”.

Plath, writing in her journal when she was mourning the loss of Richard Sassoon, identified herself with Isis: “Then I was in my black coat and beret: Isis bereaved, Isis in search, walking a dark barren street”9. So, to identify her shadow–self as Nike/Nephthys – ‘the other’ – was most appropriate.

The above interpretation of the poem, however, does not explain all Plath‘s imagery. Who is the man whose “parts” are assumed by Nike? Are we to read ‘assumes’ as ‘takes up’, as Nephthys took up the dismembered parts of Osiris and helped Isis to piece them together? If so, “a meathook” would be a cruel and unlikely tool for her to use, although perhaps appropriate to her dark, deathly powers. What are we to make of the “bright hair, shoe-black, old plastic”, which is part of a confession to the police, except that it indicates secrets? And what of the “stolen horses” linked so closely to “fornications”? Is that just a reference to the sexual energies often associated with horses and the stolen gratifications which characterize fornication and which are part of the Moon Goddess’s “abominations” which Plath described in ‘Thalidomide’?

The Egyptian’s use of the image of Nephthys on the canopic jars which held the lungs of the mummified deceased, might explain Plath’s image of Nike/Nephthys “sucking breath”, but nothing else about the couplet in which this occurs supports this.

In spite of the strong Ariel ‘voice’ of the speaker, and in spite of Plath’s careful construction of the poem, without some kind of help from the poet (Plath offered no comments on this poem) there are too many puzzles in the imagery for ‘The Other’ to be considered a good poem. This may have been the reason why Ted Hughes chose not to include it in his publication of Ariel.

The sisters Isis and Nephthys, however, and their intimate connection with wholeness and rebirth, are clearly appropriate to Plath’s own regenerative journey. And, having faced this shadowy aspect of her Spirit and acknowledged that it is an essential part of her Self, the next stage of the journey is to expose her Spirit to the all–powerful rays of the sun, which is the source of all life and growth in our world.

Yet, there is no obvious connection between ‘The Other’ and the next poem in her Ariel sequence, ‘Stopped Dead’ (dated 10 October 1962), which would be linked with The Sun (card 19) in the Tarot journey. And, according to the dates on Plath’s manuscripts, some three months and six other Ariel poems separate these two poems from each other. Nor does ‘Stopped Dead’ seem to be a sun–filled poem. Rather, Frieda Hughes has identified it as one of Plath’s “more lacerating poems”, which her father left out of his publication of Ariel because it was about his maternal uncle, Walter Farrar10. This uncle was a prosperous mill owner who, with two of his brothers, produced “cords, moleskins, khakis”11, all fabrics suitable for making trousers (or “pants”, as Plath has it in her poem).

That Plath knew this uncle, who was very close to her husband12, is clear from notes she wrote in 1956 for her story ‘All the Dead Dears’13. And he seems to be the obvious target of the speaker’s ire in ‘Stopped Dead’, where her sarcasm is directed at “Uncle, pants factory, Fatso, millionaire” – the capitalising of ‘Fatso’ and her description of him sunk, “still as a ham” in his “seven chins”, being particularly nasty. Yet, many of the other images in the poem do not make sense of this attribution.

At one moment, with a “squeal of brakes”, the speaker seems to describe a car accident, and yet the uncle is slumped in “a chair”, rather than a car seat. And how does one explain a “dead drop” so high that the viewer seems to have a view like that from an aircraft and what should be scenery, or possibly a country, looks more like a seething cauldron of molten metals? What can we make of the speaker’s urge to call the screaming of “a goddam baby” “a sunset”? Or of her comment that there is always “a bloody baby in the air”? Why in the air? And why should she think that this uncle might suspect her of wanting to murder him, like “Sad Hamlet, with a knife”, when all she wants, it seems, is to carry off his soul?

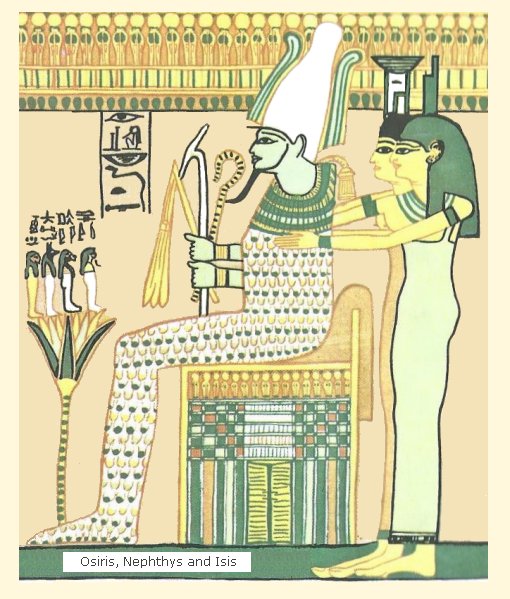

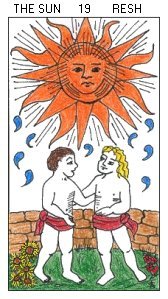

Does it help to look at some of the meanings and symbolism of The Sun card in the Tarot?

One meaning attributed to the card is that it represents a spiritual awakening, a sudden insight: a moment “rooted in immobility” in which “the newly awakened child” of the Spirit is offered, for a brief time, a sudden, brilliant vision of the world as a new and unfamiliar landscape14. Perhaps this is the dead stop of the poem’s title: but the vision revealed seems far from mystical.

The card in traditional Tarot decks depicts two small, almost naked children, twins, who embrace each other and dance together in a walled garden under the full red and gold face of the sun. Drops of dew – life-giving moisture created by the sun – fall around them; and behind them the carefully built wall suggests that they are within a Paradisal garden (like the hidden, laughing children in T.S.Eliot’s Four Quartets) and/or that they have stepped outside normal human boundaries and are now able to withstand the full, destructive, and creative power of the sun.

Rákóczi interprets this picture as showing “the Sun of Adepthood” shining on the new-born Adept, who “has the heart of a child” but is now “unified in his earthly persona and his higher individuality”15. In other words, the initiate has cleansed and re-united Body, Soul and Spirit and is now reborn as an Adept to whom the Mysteries will soon be revealed.

‘Stopped Dead’ contains a number of images which can be related to the sun but they come from a mixture of alchemical and mythological sources, few of which are depicted on the Tarot card.

The car’s wheels – “two rubber grubs” which “bite their sweet tails” – perfectly describes the Uroborus, the snake biting its tail, which is an ancient alchemical and mystical symbol of Nature and its eternal cycle of life and death: and the sun is the source of everything in Nature.

The “Red and yellow, two passionate hot metals/ Writhing and sighing”, also perfectly describes an alchemical cauldron at the final stage of the purification process by which gross matter (sometimes called lead) is turned into gold. Red represents heat: yellow, light. Combined, they represent the sun, which is the alchemical symbol for gold. The “writhing and sighing” of these metals in Plath’s poem also coveys the double meanings of alchemical symbols, where the alchemical cauldron represents the human body in which the gross matter of the soul is purified in order to release Spiritual gold.

Having just dealt with the ‘twins’ Isis and Nephthys in ‘The Other’, the naked, reborn, twin children on the Tarot card of The Sun are appropriate to this stage of the journey, but Isis and Nephthys, in Egyptian genealogy (which is often muddled) are not only wife and sisters of Osiris but also nieces of the Sun God, Ra16. So these twins could call the Sun God, ‘uncle’; and the full, round sun, source of all, symbol of gold, could be seen as a ‘fatso, millionaire’.

In another mythology the Sun God, Phaeton, rode in a chariot (sometimes called a ‘car’).

And in yet another mythology, Mithras, the Sun God of a mystical sect specifically associated with Rome, would often, in his manifestation as our earthly sun, sink (perhaps red as a ham) in the seven hills of Rome.

Looking even further, Ra was commonly depicted as an eagle (as is the sun god in many mythologies) and his sons and grandsons were represented by the smaller bird of that family, the hawk. The speaker’s view of the landscape in ‘Stopped Dead’ is akin to the perspective of the bird in Ted Hughes’ early poem ‘The Hawk in the Rain’17. And in lines which were included in a recording of Plath reading her Ariel poems but were omitted from all the published versions of ‘Stopped Dead’, there is a suggestion of a roosting place suitable for a hawk but not an eagle:

The dead stop, the height, the unidentified landscape, the bloody baby linked with a sunset, the brief “visit”, all these things fit the Tarot card’s meanings; and some of Plath’s images seem to be drawn from alchemical and/or various mythological representations of the sun. However, once again, I feel that the above suggestions are unsatisfactory, and that they come from too many different sources to be convincing. Nor do they resolve all the puzzles. Why, for instance, should the speaker be suspected of wanting to kill this uncle and steal his soul, especially if he represents the sun which is the source of all life and which in Tarot presages the imminent achievement of the journeyer’s final goal?

Even if these puzzles were to be resolved, and if Plath was indeed making the Tarot journey and living it though the creation of her Ariel poems, then this poem is still too fixed in Plath’s own personal and emotional world to be a product of actual enlightenment. It may have been an attempt to imagine such an ‘awakening’ and what it would be like to see the world anew in the all–revealing rays of the sun. However, in seeming to describe an actual living person, and in doing so in such an unpleasant way, the poem demonstrates that Plath was still struggling to extricate herself from what her daughter called the ”otherworldly, menacing landscape“ in which her ferocious Ariel voice flourished19.

Unlike ‘Stopped Dead’, Plath’s next Ariel poem, ‘Poppies in October’, (dated 27 October 1962) is a superb interpretation of the mystical meaning of its matching Tarot card, Judgment (card 20).

Judgment is the card of revelation. Its occult, mystical meaning is of a sudden, overwhelming, direct communication from the Divine Creative Source. This, for the newly awakened Adept, represents a direct call to the Spirit (the Divine spark within them) to confront all that he or she has been and done in the world, and to use their new insight – their new knowledge of their own identity and powers – in their future interaction with others.

The Judgment card of most Tarot decks alludes to the Biblical Last Judgment: the ‘call’ is mediated by a great, winged angel who blows a golden trumpet, and three figures – mother, father and child – are seen emerging from an earthly grave.

In Plath’s poem, it is the poppies, their “skirts” brighter than the October morning “sun–clouds”, which trigger the speaker’s moment of revelation – a moment in which, as one Tarot text puts it, “the heart of the visionary expands” and the “perfect, jewel-like sublimity” of the infinite is revealed20.

The title is like an exclamation of surprise at the sight of these flowers which usually bloom in mid–summer but which are flourishing in Autumnal October. And the brevity of the poem, the short, simple lines, the minimal punctuation, the sudden “astounding” blooming of the heart and the exclamation “Oh my God”, all convey the breathless wonder of the speaker.

In a world of sickness and pollution, where eyes are “dulled”, the poppies “cry open”: each bloom, like a rounded, red mouth crying out also resembles the trumpet of a Divine messenger which cries “open” to the tombs and brings clear vision to the Adept.

And, like the sick woman in the ambulance “whose red heart blooms through her coat so astoundingly“, the speaker’s heart bursts with joy and wonder at this “love-gift” which has been brought to her so unexpectedly by the ephemeral, unearthly beauty of the poppies.

The speaker herself recognizes this transcendental moment and speaks directly to her God. And her question has two meanings depending on which word is emphasised: “who am I?” or “who am I?”: thus questioning her own nature and identity and/or questioning the reason why she, in particular, has been singled out to receive this revelation – this “gift”.

Plath’s careful construction of this poem reflects not only the occult meaning of the card, but also all its other symbolism. She includes God and mankind; sky and earth; the mundane and the ephemeral; life and death. Her sick woman, bowler–hatted men and the ‘I’ who is the newly awakened speaker reflect the three figures on the card, which represent the complete life–cycle in Nature – mother, father and child.

Unlike male poets and the male writers of Biblical texts, who choose the rose as a symbol of sacred and spiritual love, purity, and mystical redemption, Plath chose the poppy – the Goddesses’ flower, in which narcosis, enchantment, death and resurrection are all symbolised.

And, in the structure of her poem, her four tercets combine the four–square, earth–bound energies with the magical Goddess–linked power of three.

In Mystical lore it is love which brings revelation, redemption and renewal. Here, in Plath’s poem, it is a “gift, a love–gift”, which brings all the alchemical elements of the world together – sky, earth, air and water – so that renewal can take place. And it is this love–gift, and the wonder it engenders, which, in the final lines of the poem, calls the speaker from the “forest of frost” into the cornflower blue “dawn” of an October morning and presages a new beginning.

Real as the gift of flowers in ‘Poppies in October’ may seem, and real as this moment of revelation is made to feel, the gift might also be seen as Plath’s own creative gift which blossomed so extraordinarily in this poem and in her ‘Ariel’ poem, both of which she dated as having been written on her thirtieth birthday, 27 October, 1962.

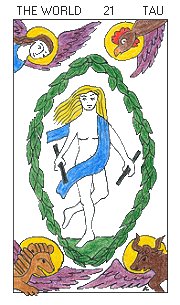

‘The Courage of Shutting Up’ (dated 2 October 1962) is the twenty–second poem in Plath’s arrangement of her Ariel manuscripts. As such, it is the last poem of the Tarot journey and it is linked with the card of The World (card 21).

Perhaps because it was written before either ‘Ariel’ or ‘Poppies in October’, is shares none of the exhilaration and power of these poems. Nor does it express the peace, balance, and harmony which mark the completion of the journey and are an essential part of the meaning of The World card.

In most Tarot decks, The World depicts a beautiful, dancing woman, naked but for a loose veil which floats around her. She rests one foot on the earth and raises the other behind her in the air. In her hands she holds two wands, or batons, and around her is a wreath of laurel or flowers. In the four corners of the card, are the four symbols of the Biblical evangelists - eagle, lion, bull and angel. The nakedness of the dancing figure reflects the innocence of a new beginning, but this is no longer the innocence of The Fool: it is an innocence and open–ness born of self–knowledge, judgment and wisdom, and it expresses psychic wholeness – the re–integration of Body, Soul and Spirit.

The figure on the card dances in air but has not lost touch with the earth. She dances (to borrow a phrase from T.S.Eliot) at “the still point of the turning world”21. And the wreath around her is a symbol of victory, successful achievement and, also, it suggests the Cosmic Egg in which all chaos is brought to order.

The Adept now, in Rákóczi’s words, is “Lord of all worlds above and below”22. The batons which the figure holds symbolize her magical power to re–unite all opposites, heaven and earth, active and passive. Her Spirit, now, joins with the four Alchemical world elements (air, fire, earth and water) which are represented in the corners of the card and which, as symbols of the Biblical evangelists, also represent the earthly power of mystical knowledge and teaching.

In Plath’s poem, however, she seems still to “walk in a ring / A groove of old faults, deep and bitter”, as she did in ‘Event’23: “Shutting up” or “quietness”24, is not the result of peace and harmony but an act of “courage”, and the speaker does not express any confidence that this is possible, nor does she resolves to do this. Instead, she rehearses the difficulties, dwelling on inner turmoil, the disturbed circling of the brain, the memories which revolve like gramophone records and which, in her imagination, segue into images of a surgeon, then a tattoo artist creating blue pictures which, “over and over”, express the same “grievances”.

The struggle to stay silent is expressed as a war. There is “artillery”; and “cannons”, torture and death. The repetition and rhythm of “bastardies / Bastardies, usages, desertions and doubleness” and of “a tattooist / Tattooing over and over”, emphasize the recurrence of old “grievances”, echo the tramp of marching feet and reinforce the military images of warfare and death.

The tongue, too, is linked with warfare, blood and punishment. It is an “antique billhook” and, like the naval ‘cat’ used for flogging, it has “nine tails”. But it does not flog, it “flays”, which is a far more bloody and vicious. And the paronomasia of ‘tails’ and ‘tales’ suggests its capacity for story-telling, deception and lying.

Even the eyes are connected with warfare, torture, deception, “death–rays” and killing. “The eyes, the eyes, the eyes” are everywhere and, as mirrors of the Soul, they may also reflect the “terrible” tortured and deathly inner state of a man.

“Do not worry about the eyes”, the speaker tells us, yet their deadly “rays” (as if looks could kill) still belong to a country (a person) who is “obstinately independent” and who, although “insolvent”, still exists. “Insolvent”, too, has the double meaning of ‘impoverished’ and also, as ‘in solvent’, of being immersed in a solvent, i.e. something which may eventually dissolve it. Neither of these meanings, however, suggests that the ‘country’ has vanished. In spite of the “folded…flags” of the eyes, the closed mouth and the guarded tongue, the careful surgeon/tattooist – the person to whom these physical attributes belong – is still present and the dangers posed by the mind and the body still exist.

Rákóczi’s commentary on The World offers no help in deciphering this poem, nor do many other Tarot texts, most of which concentrate on the successful completion of the journey. In Alister Crowley’s words, for example, the card is ”a glyph of the completion of the Great Work in its highest sense“; and just as ”The Fool represents the negative issuing into manifestation“ (i.e. birth and new beginnings at the start of the journey), so The World ”is that manifestation, its purpose accomplished, ready to return“25.

Crowley’s comment, however, does express something more than just completion. For the ordinary human being, the tarot journey is never–ending. As Ted Hughes put it at the end of his Alchemical journey of Cave Birds:26

“At the end of the ritual up comes a goblin”

The Fool who began the journey may be wiser and more self–aware by the stage at which The World is reached but she or he still carries the ‘baggage’ of a former life, and the future, with new joys and woes, must still be negotiated.

If Plath’s poem does represent The World of the Tarot, then she acknowledges this continuity. Her black disks resemble old gramophone records; her cannon and billhooks come from an earlier military age; her “engravings of Rangoon” and the stuffed animal heads “hung up” in the “library” suggests souvenirs of a past Colonial posting; and the folded flags belong to “a country no longer heard of”. All this suggest a past life. The task, now, is to live with that and to go forward into a future which will be shaped by lessons learned on this newly completed Tarot journey.

In the words of one of the few Tarot texts that do encompass this meaning, The World ”represents the synthesis of the long-sought spiritual experience with the processes of daily life“; and for the successful journeyer “a time comes to return to the World, where the experiences of spiritual encounter may be tested and manifested in the context of other living beings”27.

In the light of my examination of the first twenty–two Ariel poems, I have to conclude that Plath did use the Tarot to order her Ariel manuscripts and that at least some of the poems were written with a particular Tarot card in mind. But given that the chronological order in which the poems were written is markedly different to the order in which the cards are arranged in a traditional Tarot journey, her method of using the cards is still a puzzle.

It is tempting to suggest that Plath followed the pattern of the Tarot journey in the traditional way, then dated her manuscripts some time after she wrote the poems in order to disguise what she was doing and to abide by the strictures on revealing occult secrets. Plath’s copy of The Painted Caravan was well used and she would certainly have read Rákóczi’s opening remarks, in which he spells out the “outer and inner pledge of secrecy” imposed on any Gypsy who uses the Tarot, and the penalties for violating this pledge, which include the psychological penalty of “a terrible disruption of mental powers”28. Plath would certainly have wanted to avoid that.

Ted Hughes, as well as noting that Plath’s Ariel manuscripts were ”carefully ordered“29, wrote that from the first Ariel poem Plath “suddenly started saving all the draft pages, which she had never bothered about before. She not only saved them, she dated them carefully”. At the same time, he commented “I don’t know how grossly she might have exaggerated, but there certainly were days when she wrote three poems, or rather finished three”30.

Plath’s journals confirm her propensity for exaggerating, but the evidence of the Smith College Ariel archive31 does not support a supposition that she had any ulterior motive in keeping and dating all her drafts, or that she deliberately misdated all those poems.

In the Smith College Archive, unlike the poems written before ‘Little Fugue’ (dated 2 April 1962) and those written after ‘Mary’s Song’ (dated 19 Nov. 1962), each group of drafts for each poem written between 2 April 1962 and 2 December 1963 (except for ‘The Other’) contains holographs (hand–written) and/or typescripts written on pink Smith College Memorandum paper.

In addition to this, the majority of these holographs and typescripts have draft pages of The Bell Jar, Version 2. on the verso, and many of these pages from The Bell Jar are in reversed but consecutive order following the chronology of the dates on the Ariel poems.

For example:

|

‘The Couirage of Shutting up’ ‘The Bee Meeting’ ‘The Arrival of the Bee Box’ ‘Stings’ ‘The Swarm’ ‘Wintering’ |

2 Oct. 1962 3 Oct. 1962 4 Oct. 1962 6 Oct. 1962 7 Oct. 1962 9 Oct. 1962 |

Verso: The Bell Jar, version 2 Verso: The Bell Jar, version 2 Verso: The Bell Jar, version 2 Verso: The Bell Jar, version 2 Verso: The Bell Jar, version 2 Verso: The Bell Jar, version 2 |

Ch.6 Ch.6 Ch.6 Ch.5 Ch.5 Ch.4 Ch.4. |

pp.3,4 pp.2,6,7,10,11,12 pp.9,8 pp.11 pp.1,2,5,6,7,8 pp.7,8,9,10,11,12,13 pp.5,6,8,9 |

One consecutively dated group of poems – ‘A Secret’, ‘The Applicant’, ‘Daddy’, ‘Medusa’, ‘The Jailor’ and ‘Lesbos’ (dated 1962 October 11,12,16,17,18 respectively) – stands out as being different, because it has drafts of Ted Hughes’ unpublished play, The Calm, on each verso. And there are several other anomalies in this seemingly regular pattern shown by the Smith College Ariel Archive drafts, although whether these are significant is debatable.

There are no holographs in the Smith archive for ‘Magi’, ‘Morning Song’, ‘Barren Woman’ or ‘Tulips’, all of which were written before January 1962, and all of which were included amongst the first twenty–two Ariel poems32.

‘The Other’ exists as undated holograph pages numbered by Plath 1 – 5, the verso of which are typescript pages of poems “probably from The Colossus”. The date ascribed to ‘The Other’ first appears on a typescript which has been numbered by Plath as page 6 and which also has part of a Colossus poem on the verso. Unlike all the other 1962 poems, none of the Smith College manuscripts for this poem are on pink Smith College Memorandum paper. This is also one of the very few poems not written on recycled drafts of The Bell Jar.

The first undated holograph pages of ‘Death & Co.’ (1 un–numbered and one numbered ‘2’ by Plath) and one undated typescript page (numbered 3); plus the first dated typescript page (dated 12 November 1962, and numbered 4), are all on pink Smith College Memorandum paper and have nothing on the verso.

However, four further undated, un–numbered typescript pages of ‘Death & Co.’ have the poems ‘Totem’, ‘The Munich Mannequins’, ‘Child’ and ‘Paralytic’ on the verso, all of which were written in 1963. ‘Gigolo’ (also written in 1963), occurs on the verso of yet another ‘Death & Co.’ typescript but this time the poem is marked “revised 1962 Nov 12”.

Since notes for ‘Death & Co.’, typed by Plath and dated 13 Dec. 1962, are included amongst others written for Douglas Cleverdon for a BBC programme of new poems, it seems that the 1963 poems were written later, on recycled draft sheets of ‘Death & Co.’. Yet, this suggests that there may well have been more drafts than are currently held in the archive.

One other poem raises a similar possibility. ‘Thalidomide’ exists in the Smith College Archive as four, undated, holograph pages on pink Smith College Memorandum paper with nothing on the verso of any of these pages. Two typescripts, similarly on pink paper with nothing on the verso are dated 1962 Nov.4. But one further typescript, revised but undated, has the 1963 poem ‘Balloons’ on the verso.

In the end, the way in which Plath approached the Tarot when writing her Ariel poems and arranging her Ariel manuscripts is impossible to determine. My guess is that she was inspired by The Painted Caravan and began to use the Tarot cards in a random way to prompt her imagination. Then, at some stage, she recognized that her own long quest to find healing through her writing was paralleled in the Tarot journey and that this could be one more aid (a powerful magical aid, too) to achieving her goal: so, she decided to order her poems to conform with it. Many of her poems, like ‘Morning Song’ and ‘Tulips’, already suited particular stages in the Tarot journey but some poems she revised and rewrote; and some she wrote specifically for a particular stage and card, and later inserted them among her manuscripts.

Words, as Plath wrote are like axes. The echoes of their strokes can travel “off from the centre like horses”33. And there are so many echoes in Plath’s poetry – echoes of her life, the people she knew, her loves and her hates; echoes of mythology, folk–tales and magic – that her poems can mean many different things to many different people. Perhaps she did use the Tarot in Ariel, perhaps not. Whatever one believes about that, Plath’s Ariel poems are remarkable poems written, as Ted Hughes said, “with the full power and music of her extraordinary nature”. Ariel, as he also said, “is not easy poetry to criticize. It is not much like any other poetry”. But “It is her… It is just like her – but permanent”34.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

1. Hughes, T. ‘Sylvia Plath and her Journals’, Winter Pollen, p.187.

2. Winter Pollen, p.188.

3. Kukil, K. (ed.) The Journals of Sylvia Plath, 26 February 1956, p.212.

4. Rákóczi, B. The Painted Caravan, pp.63-4.

5. Egyptologist Wallis Budge writes that the ‘House’ was interpreted as being the night sky but may be a temple or abode. This Goddess is also known as Nebt–Heb (Lady of the body). Budge, The Gods of the Egyptians, Vol.2, Dover Publications, N.Y. 1969, pp.254-60.

6. Budge, W. The Gods of the Egyptians, Vol 2. p.258.

7. Isis is better known as Osiris’s wife but she was both his wife and his sister. Nephthys was sister to Isis and Osiris, and sister and wife of Seth.

8. Budge, W. The Gods of the Egyptians, Vol 2, p.255.

9. Kukil, K. (ed.), The Journals of Sylvia Plath, 10 March 1956, p.234.

10. Hughes, F. Foreword to Ariel: The Restored Edition, p.xvi.

11. Ted Hughes describes these brothers’ mill–products in his poem ‘Sacrifice’, Keegan, P.(ed.) Ted Hughes Collected Poems, Faber, 2003, pp.758-60.

12. In a letter to János Csokits, Ted Hughes described Walter Farrar as “My uncle – the patriarch of my family and one of my dearest friends”. Reid, C.(ed.) Letters of Ted Hughes, May 1976, p.376.

13. Plath’s journal notes for ‘All the Dead Dears’, which was later published in Johnny Panic and the Bible of Dreams (Faber , 1979, p.177-84.), include “central tragic figure – Uncle W”. Kukil, K.(ed.) The Journals of Sylvia Plath, 31[a] 1956, p.580.

14. Irwin, L. Gnostic Tarot, Samuel Weiser Inc, 1998, p.320.

15. Rákóczi, B. The Painted Caravan, p.64.

16. Isis, Nephthys and Osiris were all born of Light (Shu) and Air (Tefnut), Earth (Geb) and Sky(Nut), all of which were created by and from the Sun–God, Ra. Osiris, however, came to be regarded, and worshipped, as the dark brother of Ra. He was in charge of the Underworld, as Ra was in charge of the Upper world. As Osiris’s brother, Ra became uncle to Isis and Nephthys.

17. Ted Hughes: Collected Poems, p.19.

18. Quoted by John Hopkins, Tuesday March 23, in the on–line Sylvia Plath Forum, March 1999. The reading can be heard on YouTube in ‘Sylvia Plath reads from Ariel (2)’.

19. Hughes, F. Foreword to Ariel: The Restored Edition, p.xii.

20. Irwin, L. Gnostic Tarot, pp.326-7.

21. Eliot, T.S. Four Quartets, Faber, 1972, p.15.

22. Rákóczi, B. The Painted Caravan, p.67.

23. Sylvia Plath: Collected Poems, Faber, 1981, p.195.

24. An alternative title for this poem before publication was ‘The Courage of Quietness’.

25. Crowley, A. The Book of Thoth, Weiser, Maine, 1985, p.118.

26. Ted Hughes: Collected Poems, p.440.

27. Irwin, L. Gnostic Tarot, p.330.

28. Rákóczi, B. The Painted Caravan, p.8. Such vows of secrecy are common in Western mystical tradition; and the maxim often adopted by the Magus (the Master) is “To Know, to Will, to Dare, and to be Silent”. This maxim was first recorded in Transcendental Magic by Eliphas Levi (1810-1975), whose extensive study of mysticism and magic was certainly known to Ted Hughes.

29. Hughes, T. ‘Sylvia Plath and Her Journals’, Winter Pollen, p.189.

30. Hughes, T. ‘Publishing Sylvia Plath’, Winter Pollen, p.167.

31. I am grateful to Karen Kukil, Associate Curator of Special Collections, William Allan Neilson Library, Smith College, Northampton, MA, for providing me with a draft of her finding aid for the Sylvia Plath Collection. My information about the Ariel holographs and typescripts is drawn from this draft.

32. ‘Magi’ and ‘Morning Song’ (though not a complete run of manuscripts/typescripts) are held by the Lilly Library, as is ‘Barren Woman’ under an earlier title, ‘Small Hours’. ‘Tulips’ is held by Harvard. Plath sent the worksheets for ‘Tulips’ to Jack Sweeney on 22 August 1961; and the other three poems were part of the ‘scrap paper’ Plath sold to Indiana University through a London bookseller in November 1961. (Thanks to Peter Steinberg for this information).

33. ‘Words’, Sylvia Plath: Collected Poems, p.270.

34. Hughes, T. ‘Sylvia Plath: Ariel’, Winter Pollen, p.162.