Sylvia Plath, Ariel and the Tarot (3)

‘Tulips’, ‘A Secret’, ‘The Jailor’, ‘Cut’.

© Ann Skea.

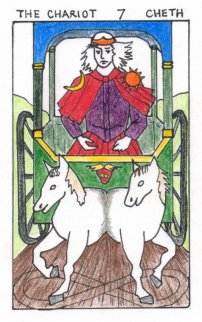

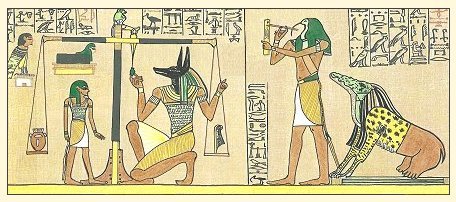

“Tulips” (dated 18 March 1961), is paired with The Chariot, card 7, and, as with earlier poems, it seems to have little relationship to the usual divinatory readings of this card, which are to do with self-confidence, success, excitement and balance.

In spite of this, Plath’s poem describes perfectly the state of an initiate who has just been reborn and is ready to begin the next part of the Tarot journey. Such an initiate has, according to Rákóczi, “suffered the loss of one half of himself, the youthful beloved”, and must now “follow the chariot of Pluto into the next world and search for that which was lost in order that the two halves may be reunited and a balance restored”1.

The speaker in ‘Tulips’ is like one who has been reborn into a sort of limbo. What she describes is exactly the loss of self – the loss of persona – which marks the start of the second stage of the Tarot journey. She is “nobody”. She has given away her name and her “day-clothes”, as if giving up her everyday identity. She has given away her “history” and her “body”; has “lost herself” (her self), and is learning peacefulness in a place where everything is wintery, “white” and “quiet”. And she has become “just an eye” observing the passing figures of nurses.

The eye/she, is, like a new-born initiate, a “stupid pupil”, a passive observer. She is “sick of baggage” – which is linked in her mind and in the lines of the poem, with her “husband and child”, and “family”: and the ambiguity of “sick with” encompasses ‘tired of’ and ‘made sick by’ these emotional ties. Now, she has been “swabbed” clean of her “loving associations” and of all material things and this bathing by the impersonal nurses is like a baptism: it washes away her old life and it leaves her “pure”, “empty”, peaceful and “free”: in a state such as “the dead close on”.

This giving up and washing away of all physical, material and emotional attachments, and the religious imagery of the poem, all suggest the death-rebirth of an initiate.

Now, gradually, her re–emergence into life is prompted by the tulips and described, first, through their assault on her senses – sight, sound, weight and touch. She is dragged from her stasis and contentment into a new and terrifying place where she – “flat, ridiculous, a cut-paper shadow” – stands as nothing, faceless and effaced, before two dangerous and terrifying powers of nature: the sun; and the earth-grown tulips, which seem to her to be both oxygen–eating plants and dangerous, voracious animals.

Starting with her feelings of humiliation and fear, the tulips gradually drag the speaker into awareness of the turbulent world around her: they “concentrate” her attention so that, in the final images of the poem, she becomes conscious of the beating of her heart, and links her heart and the flowers with love. Both hearts and love are potent religious and spiritual symbols, appropriate to a spiritual quest.

Finally, with heart and mind reunited, salt water, “like the sea” which is the traditional symbol of the subconscious, provides the speaker with a first taste of her connection with some as yet distant place where wholeness and health can be attained. In terms of the Tarot journey, now, when the initiate must “follow the chariot of Pluto” (who is the god of the underworld and who in Jungian psychology presides over the subconscious), the speaker’s new awareness would indicate that the examination of her inner self (her buried shadow–self; her subconscious; her heart and soul) is about to begin.

Yet, however appropriate this poem is for this stage of the Tarot journey, it seems unlikely that Plath was using the Tarot to shape it when she wrote it. It was written just nineteen days after she had her appendectomy (28 February 1961) and it is a superb and realistic evocation of the dream–like, disoriented state of someone recovering, in hospital, from an anaesthetic. It is interesting to compare it with her journal entry for 27 February 1961, ‘In Hospital’, at which time she was “still whole” and very observant. She wrote “This is a religious establishment, great cleansings take place”; and, of the flowers: “a helpful inmate...brings the flowers back, sweet-lipped as children. All night they’ve been breathing in the hall… ”2.

Clearly, the religious elements of the poem were already there in her mind when she wrote it, as was the personification of the flowers. This does not mean, however, that Plath did not see how absolutely right this poem was for pairing with The Chariot card when she ordered her Ariel manuscripts.

Unlike ‘Tulips’, the imagery of ‘A Secret’ (dated 10 October 1962) has no coherence. In quick succession we have a policeman, a one-eyed person, an African Giraffe and a hippopotamus (of an extinct species), a brandy finger (like a brandy-snap biscuit) “roosting and cooing”, a grotesque, bastard baby in a bureau drawer or in a stoppered bottle of stout, mayhem in the Place de la Concorde, and a stumbling, speaking, dwarf baby with a knife in its back. The only thing which holds this poem together is the bitter sarcasm of the speaker; and a dirty secret which must be levered out with a knife.

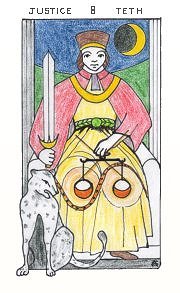

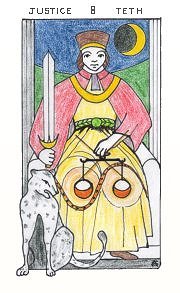

Nothing in all this suggests the card of Justice, which stands for balance, stability, discernment and tranquillity. Nor, even if the card and its meaning were reversed, does this provide any enlightenment about the imagery in the poem, although it is suitably chaotic.

Rákóczi writes that this card represents “the judgment of Osiris, where the soul of the initiate is being weighed”. He mentions “more licentious sects” where “we have the exaltation of the prostitute as a saint and the saint treated as one who is impure”; and he notes that Gypsies “call this card the Magdalene card” and place it under the patronage of Sara, the Negress saint of the Romany3.

Perhaps, in the poem, there is an element of the figure of Justice being treated as one who is impure. And perhaps the “Edeny greenery”, the “African giraffe”, the “Moroccan hippopotamus” and the “jungle gutturals” are associated with Black Sara, who, according to some accounts, was an Egyptian Abbess of a convent in Libya, North Africa. But this is mere speculation.

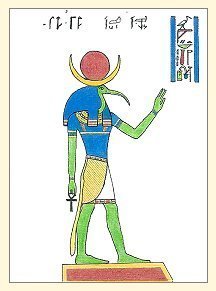

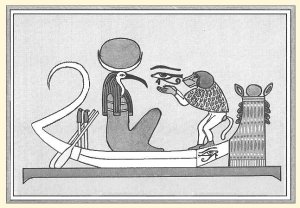

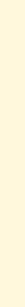

Given the stage of the Tarot journey that this poem should reflect, a stage at which the initiate must begin the journey through the underworld of their own subconscious and examine their inner self, let me offer three pictures which may throw some light on Plath’s imagery. All three are taken from Egyptian papyri of The Book of the Dead, which illustrate the place of judgment in which the heart of each newly deceased person is weighed in a balance which is supervised by the god, Thoth (Tehuti).

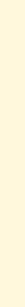

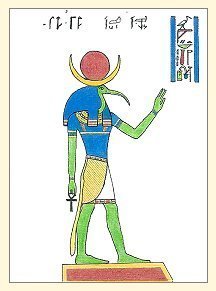

Thoth is the god whose will and power keep the forces of heaven and earth in equilibrium; he is the scribe of the gods and the guardian of the gates of the underworld. Although he is a Moon god, he is known as the ‘Eye of Ra’ – the mind, reason, and understanding of the great Sun god Ra. And he is also “the great god of words”, who can teach the words of power and “the manner in which to utter them”4. He is believed to be the originator of the Tarot.

My first picture of Thoth shows him in his typical form as a human with the head of an ibis. Half his body is blue, and blue is the colour which the Egyptians usually associated with him, although he is often shown as other colours. He stands, in profile, with one foot forward and his left arm raised, “holding up one palm” like a policeman.

The second picture shows Thoth standing before the scales on which the heart of the deceased is being weighed against a feather. He has his stylus and a papyrus tablet in his hands ready to record the result.

Behind him is a creature – part lion, part crocodile, part hippopotamus – waiting to devour those who fail the test. All these animals, especially the hippopotamus, were regarded as fiends of the dark which must be overcome5. No giraffes are mentioned in the Egyptian texts.

Behind him is a creature – part lion, part crocodile, part hippopotamus – waiting to devour those who fail the test. All these animals, especially the hippopotamus, were regarded as fiends of the dark which must be overcome5. No giraffes are mentioned in the Egyptian texts.

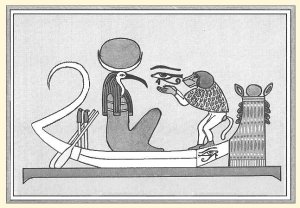

The third picture shows Thoth seated in a boat with his associate the ape (a form of Thoth as Lord of Divine Words) who holds before him the Utchat – the Right Eye of Ra (the sun) – which he is ferrying through the underworld.

On the prow of the boat, is Thoth’s own Utchat – the Left Eye of Ra – which represents the moon. So Thoth, seen in profile in this picture, has two eyes: all the other figures in the Book of the Dead are similarly seen in profile and have only one eye.

On the prow of the boat, is Thoth’s own Utchat – the Left Eye of Ra – which represents the moon. So Thoth, seen in profile in this picture, has two eyes: all the other figures in the Book of the Dead are similarly seen in profile and have only one eye.

Perhaps this is taking speculation too far. Being one–eyed, of course, is also a common metaphor for not seeing things clearly or for seeing only one side of something.

I offer one more suggestion: Since what is necessary at this stage is self–examination, the speaker in the poem may be a divided self, one half policeman interrogator, the other, the interrogated. This may explain why, for most of the poem, it is unclear who is speaking and who is being spoken to. Only when lines are in inverted commas does it appear that two people are present, as in lines 33 and 34: “Do away with it altogether.”/

“No, no, it is happy there”. These lines, however, might still be a single speaker’s sarcastic mimicry of an authoritarian figure.

In the end, none of the above suggestions fully resolve the puzzles of this poem. This may be one reason why Ted Hughes chose not to include it when he edited the first publication of Ariel, although it could also fit into what Hughes called “the more openly vicious” poems, which he left out6.

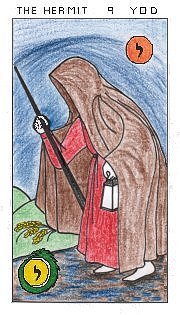

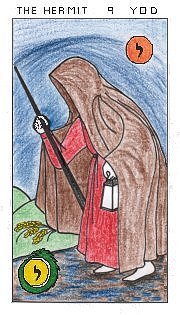

‘The Jailor’ (dated 17 October 1962) is the ninth poem of the Ariel sequence and should represent the Tarot Hermit (card 9).

Nothing about this poem conforms to any representation of the Hermit in Tarot teachings. He is one who carries a light in the underworld. He is ‘The Sage’, the ‘Old One’ who represents “prudence, truthfulness, justice, wisdom, courage, patience and the like”7, and he is regarded as the initiate’s guide to inner wisdom and self–awareness.

In the place of Justice, the light of the Law shone upon the initiate, whose sins are forgiven but must be paid for, and Rákóczi writes that this card “corresponds to the Lord of Karma who allocates the rewards and penalties after the weighing of the lost soul”8.

In reverse, the Hermit’s energies are said to represent regression, retreat, introspection, and a turning away from the light and from guidance. This is very different to regarding the Hermit as a jailor.

There is certainly punishment in Plath’s poem, but there is no sign of the Tarot Hermit. Nor is there any indication that her speaker is taking a step forward in the initiatory journey. The jailor, here, is a torturer: one who hurts the speaker for her dreams “of someone else entirely”. He coldly inflicts obscene and horrific punishments. He is associated, too, with both the dark and the light; and his existence depends on the speaker’s presence. Three times in the final stanza his needs are questioned; and three times his need for his victim is specified. This is no ordinary lawful punishment for sins.

Anne Stevenson, in Bitter Fame, regarded this poem as part of Plath’s exorcism of her inner demons and she suggested that it “attacked her longing for her husband”9. Yet, it could equally well represent Plath’s confrontation with “Johnny Panic” – “The Great Dream-Maker himself” – whose motto is “Perfect fear casteth out all else”, and whose “love is the twenty-storey leap, the rope at the throat, the knife in his heart”10. Plath’s story, ‘Johnny Panic and the Bible of Dreams’ reflects much of her own experience with paralysing fear. “Paralysis again”, she wrote in her journal on 4 November 1959, “I wonder, will I ever be rid of Johnny Panic?”11.

Now, through the speaker in her poem, in the last two stanzas Plath “imagines” him “impotent as thunder”; imagines him “dead and away”; and, with the three repetitions of ‘Do without’ in the final stanza (each in a separate line so that it can be heard as a command) and the three repetitions of ‘do’ in the final line, she performs a magical ritual of banishment:

“Do without fevers to eat”

…

“Do without eyes to knife”

…

“Do, do, do without me”

In the incantatory rhythms of the poem if spoken aloud, as Plath said all the Ariel poems were as she wrote them12, and with its triple repetitions, occultists would consider this to be powerful magic.

This has nothing to do with Tarot: but a great deal to do with what Ted Hughes called Plath’s constant and continuing work towards “resurrection of self” and the defeat of “everything that had held her in the grave for ‘three days’, The Other”. In each poem in Ariel, in Hughes’ words, “the terror is encountered head on, and the angel [The Other] is mastered and brought to terms”13.

In the light of these comments, ‘The Jailor’ does not represent a specific step in a Tarot journey but can be seen as self–administered psychotherapy of the sort provided by the “psyche–doctors” for Harry Bilbo and other Johnny Panic “converts” in Plath’s story, ‘Johnny Panic and the Bible of Dreams’14.

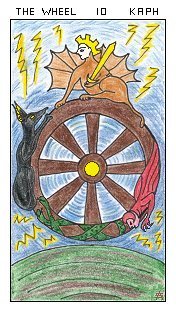

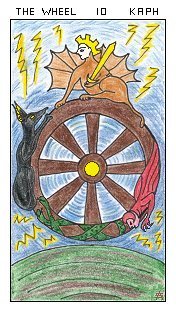

‘Cut’ (dated 24 October 1962) occupies the position of card 10, The Wheel of Fortune. Traditionally, this card represents change, chance, transformation: it is the Wheel of Life, Fate, and its energies are those of an inevitable, dynamic process which is beyond our control.

At first reading, apart from the accidental cutting of the speaker’s thumb, there seems little to relate Plath’s poem to the traditional meanings of this card.

Certainly, there is a change of mood compared to the previous poem. The speaker in the poem is excited, thrilled by the sudden accident which has occurred. This is “a celebration”. And she is playful, too, giving her thumb an identity of its own which is reminiscent of Thumbkin in the children’s finger-play game15. Even the “million soldiers”, the “Redcoats” which “run” from “the gap”, are more suggestive of ‘all the King’s horses and all the King’s men’ of nursery rhyme fame than of red blood cells flowing from a cut. Her query: “whose side are they on?” encompasses the Redcoat soldiers and the physical response to a cut – a flow of blood seems to endanger life and yet the blood contains elements which bring about coagulation and healing.

And perhaps because Plath dedicated this poem to her newest baby–sitter, “the prettiest, sweetest local children’s nurse” Susan O’Neil Roe16, this element of story–telling runs throughout the poem, although adventure stories about scalped pilgrims and Kamikaze assassins are hardly suitable for babies.

There is a suggestion of a turning wheel, too, in the energy of the poem: the flow of events; the global imagery which also moves through time (American pilgrims, Indian scalping; a Japanese assassin; the white–hooded Ku Klux Klan; a Russian babushka17); dizziness; and the “Mill of silence” (whatever its meaning); all convey dynamic power.

Beyond that, however, there is little obvious connection with the deeper meaning of the card at this step of the Tarot journey.

For the Tarot initiate who has been taken down into the darkness of the material world (and of the subconscious) and has now completed the ‘Second Initiation’18, the descent is over and the ascent towards the Wisdom of the Mysteries is about to begin. Questions about the self must be answered (as the sphinx–like figure above the wheel on the card indicates); and insight must be gained so that the initiate can live in harmony with the world’s energies.

Surprisingly, Rákóczi’s disapproving comment about heretical teachings in which “The body and soul had to be, as it were, slain and desecrated, or at least soiled and scarred, before contrition and absolution were of any value”19, might be linked to the “tarnished” bandages and to “Dirty girl/ Thumb stump” in Plath’s poem.

The sphynx’s sword, too, suggests that some sacrifice must be made. But is the sliced off tip of a thumb enough of a sacrifice? The speaker certainly likens it to a trepanned head, and this is usually a procedure which a surgeon undertakes in order to effect healing.

Also, the metaphorical carpet of blood onto which the speaker in the poem steps, comes “straight from the heart”; her “thin/ Papery feeling” might be dizziness due to the accident or it might suggest the leaving behind of material attachments; and the “Mill of silence” is linked with the circling gauze bandage on the “balled pulp” of the thumb but it could also connect the speaker’s heart to her inner world and, so, to the cycles of time, the cosmic wheel, the whirlings of the heavens.

All these things may suggest some deeper meaning to Plath’s poem. However, given the euphoric tone of the letter she wrote to her mother the day before she wrote the poem, and her plea for forgiveness for her “grumpy, sick letters of the last week” , ‘Cut’ may simple reflect an actual change in her fortunes and moods. Both possibilities, of course, could be true.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

1. Rákóczi, The Painted Caravan, p.40.

2. Kukil, K (ed.), The Journals of Sylvia Plath, 29 March 1958. p.599.

3. Rákóczi, The Painted Caravan, p.43. Saint Sara (Sara–la–Kali) is venerated at the thirteenth century church of Saintes Maries–de–la-Mer, Isle de la Camargue, France. Her festival days, 24-25 May, are celebrated each year and are attended by many Romany pilgrims.

4. Wallis Budge, E.A. The Gods of the Egyptians, Vol.1. Dover Publications, N.Y. 1969, pp.402-415.

5. A number of papyrus pictures show the hippopotamus being speared by the god Horus to protect Thoth. Yet, the animal was worshipped by the Egyptians and there was, in The Book of Slaughter of the Hippopotamus, a hippopotamus goddess, called Rertu, who was regarded as beneficent.

6. Hughes, T. ‘Publishing Sylvia Plath’, Winter Pollen, Faber, 1994, p.166.

7. Rákóczi, The Painted Caravan, p.43.

8. Rákóczi, The Painted Caravan, p.44.

9. Stevenson, A. Bitter Fame, Viking, 1989, p. 268.

10. Plath, S. Johnny Panic and the Bible of Dreams, Faber, 1979, pp.26 and 33.

11. Kukil, K. The Journals of Sylvia Plath, p.522.

12. Plath interviewed by Peter Orr of the British Council, 30 October, 1962. This interview is available on the internet.

13. Hughes, T. ‘Sylvia Plath and her Journals’, Winter Pollen, Faber, 1994, p.187.

14. Plath, S. Johnny Panic and the Bible of Dreams, pp.26-7.

15. With only the thumb on one hand exposed from a clenched fist, the mother asks: “Where is Thumbkin? Where is Thumbkin? Here I am.” (exposes thumb the other hand). “Here I am. How are you this morning?” (bowing the first thumb). “Very well I thank you” (bowing the other thumb).“ Run away. Run away” (conceals each thumb in turn). The game is repeated for ‘Pointer’, ‘Tallman’, ‘Ringman’ and ‘Smallman’.

16. Plath, A. (ed.), Letters Home, Faber, 1976, pp.474-5. Letter dated 23 October, 1962.

17. ‘Babushka’ is the name for an elderly Russian peasant woman; and for the folded headscarf which she wears and which, in the poem, is likened to the bandage on the thumb/head.

18. Rákóczi, The Painted Caravan, p.47.

19. Rákóczi also links the Wheel of Fortune card with the Wheel of Law. The Painted Caravan, p.45.

Sylvia Plath, Ariel and the Tarot text and illustrations. © Ann Skea 12 January 2013. For permission to quote any part of this document contact Dr Ann Skea at ann@skea.com

Go To Next Chapter

Behind him is a creature – part lion, part crocodile, part hippopotamus – waiting to devour those who fail the test. All these animals, especially the hippopotamus, were regarded as fiends of the dark which must be overcome5. No giraffes are mentioned in the Egyptian texts.

Behind him is a creature – part lion, part crocodile, part hippopotamus – waiting to devour those who fail the test. All these animals, especially the hippopotamus, were regarded as fiends of the dark which must be overcome5. No giraffes are mentioned in the Egyptian texts.

On the prow of the boat, is Thoth’s own Utchat – the Left Eye of Ra – which represents the moon. So Thoth, seen in profile in this picture, has two eyes: all the other figures in the Book of the Dead are similarly seen in profile and have only one eye.

On the prow of the boat, is Thoth’s own Utchat – the Left Eye of Ra – which represents the moon. So Thoth, seen in profile in this picture, has two eyes: all the other figures in the Book of the Dead are similarly seen in profile and have only one eye.