My examination of the first three poems in Ariel: the Restored Edition would seem to suggest that Plath was writing poems based on the Tarot cards and doing so in order to make an initiatory Tarot journey. If this was her plan, then, as with any religious or spiritual initiation, she would have needed to work step–by–step through each stage and this would have taken her through the cards in numerical order, from The Fool (card 0) to the World (card 21). At each step, she may have written several poems, one after the other, examining and attempting to balance all the energies, (good and bad) represented by that particular card. And from these poems she would have chosen the one which she considered the best for her Ariel book.

However, the position of the Ariel poems within the broader framework of poems from which she chose (Ted Hughes describes these as the poems written after the publication of The Colossus in October 19601) does not support this view. The ordered sequence of all forty poems in the restored Ariel, when compared to chronological order in which they were written, appears to be random (see list).

The earliest poem among the Ariel manuscripts is ‘You’re’, which is dated January/February 1960. The latest, is ‘Death & Co.’, dated 12-14 November 1962.

Twenty-one months and sixty poems separate ‘Morning Song’, the first poem in the restored edition of Ariel, (19 Feb. 1961) from ‘The Couriers’ (4 Nov. 1962) which is the second poem. Many other Ariel poems were written during that time, including ‘The Rabbit Catcher’ (21 May 1962), which is the third poem in the book and which was written more than five months before ‘The Couriers’.

Other poems, even those written on the same or consecutive days, are separated in the book: ‘Ariel’ and ‘Poppies in October’, for example, both dated 27 October, have become poem 15 and poem 21 respectively. ‘Daddy’ (12 Oct. 1962) and ‘Medusa’ (rejected title ‘Mum:Medusa’2), (28 October 1962), which might be considered very appropriate poems for the archetype Father and Mother figures of the Tarot’s Major Arcana – The Emperor and The Empress – are widely separated, placed in reverse order from that in which they were written, and are not among the first twenty two poems which represent the initiatory steps of the Tarot journey where The Emperor (card 4) and The Empress (card 3) appear.

We do not know what criteria Plath used when she selected her Ariel poems from among the many others she had written from 1960 onwards. Ted Hughes wrote that “when she was assembling a book her self-criticism went up a notch”3; and “a poem was always ‘a book poem’ or ‘not a book poem’”4; but he says nothing about the way in which she arranged them.

I am aware, too, that there has been scholarly debate about the finality of the order in which Plath left her Ariel manuscripts. In particular, Tracy Brain, in her paper, ‘Unstable Manuscripts: The Indeterminacy of the Plath Canon’, examines Plath’s editing of her Ariel poems, the changes that she constantly made to text, punctuation and spelling, and the last-minute changes to their order which are indicated by handwritten notes and parentheses on a duplicate contents page and on the original title page. Brain concludes that “Plath’s vison [of Ariel] cannot be perfectly ascertained or reproduced” and that “the Ariel we have, as polished as it is, should only be regarded as Plath’s latest draft”5.

In spite of that, as Ted Hughes wrote in his lengthy examination of Plath’s creative process, by December 1962, “the book lay completed, the poems carefully ordered”. And given what Hughes called Plath’s “instinct for nursing and repairing the damaged and threatened nucleus of self”, a process which he saw throughout her work and which he likened to a Jungian, alchemical process of death, gestation and regeneration6, it is entirely possible that she used The Painted Caravan as her guide and chose to arrange her Ariel poems in a pattern which reflected the healing Tarot journey.

Whether Plath wrote any of the Ariel poems with a particular Tarot card in mind, remains to be seen, but I will continue to take the poems as published, and in the order in which they are published in Ariel: The Restored Edition, and to examine them in the light of the Tarot journey to see whether any clearer pattern emerges.

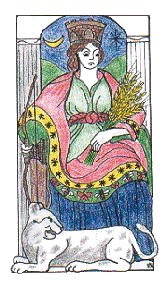

If, as is possible, the first three poems of Ariel show Plath adopting the persona of a figure on the first three Tarot cards – Fool, Juggler/Hermes, and High Priestess – then ‘Thalidomide’, the fourth poem in Ariel (dated 4-8 November 1962) is quite different. Its matching Tarot card is The Empress, the World Mother, fecund Mother Nature, creator of life and also (because worldly life is transient) the bringer of death.

Rákóczi writes that the initiate reaching this step “learns from her the secrets of nature” and is taught to call up and command “all female divinities and elemental spirits of earth, air, fire, and water”, this includes good and evil spirits. Skill in “the arts, crafts and sciences” will also be made theirs1.

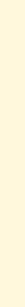

In many ways, ‘Thalidomide’ exemplifies the results of such learning. The speaker in ‘Thalidomide’, however, is not an ‘Earth Mother’, nor is she unafraid of the earth’s elementals. Rather, she fears the Empress’s deathly power – her “reversed” power as Lilith, Queen of the Night.

In her journals Plath expressed fears of bearing “an idiot or crippled child” 2. And the terrible deformities that she describes in the poem are those of children whose mothers took Thalidomide during pregnancy3. Yet, she conjures Lilith – the willow–dwelling screech owl – into this poem; and her speaker wonders “what glove/ What leatheriness” has protected her from the moony “abominations” of this Goddess’s “shadow”.

The imagery Plath uses in ‘Thalidomide’ is hallucinatory and often confusing. Some of it can only be understood if you know that a powerful, demonic Moon Goddess like Lilith is present. But although Plath was already skilled in some of the arts which the Empress teaches, even a Tarot Master would hesitate to summon Lilith into existence, if only on a page.

Lilith was Adam’s first wife who, having been created from earth at the same time as him, regards herself as his equal and refuses to obey him and lie beneath him. Uttering the name of God, she flies off and leaves him. At God’s intervention, and because she refuses to return to Adam, she is banished to the underworld and becomes a demon who must deliver to God 100 of her offspring each day. So, she preys on unprotected children, and she visits men in their dreams, arouses them or copulates with them, and bears hundreds of children from their spilt sperm. Those who are not delivered to God as payment for leaving Adam, she brings up as spirits and demons. She is sometimes a screech–owl; and she is sometimes a hairy night–monster. She is known as ‘Primordial Lilith’, ‘Ancient Lilith’, ‘Grandmother Lilith the Great’, ‘Great Whore’, ‘Tortuous Serpent’, and ‘Blind Dragon’. And she is immortal.

‘Thalidomide’ begins well enough, with an image of the half–moon – the “half-brain, luminosity” of which, with its dark patches and irregularities, prompts thoughts in the poem’s speaker of wrongness and abnormality. The half-moon is quickly personified and linked with a spider4 whose “shadow” is linked to grotesque deformities. But what sort of protection would a leathery glove provide from such a ‘shadow’? Only if you know of the Moon Goddesses’ association with owls, might you associate this with the leather gauntlet worn by those who have tamed raptors and who use such a glove as protection from the bird’s threatening claws. Even then, in the context of the poem this makes little sense.

And what are we to make of this “thing” – this “love/ Of two wet eyes and a screech”, for which the speaker carpenters a space? Since the poem is about Thalidomide babies, it is tempting to assume that the speaker has already given birth once (protected by that leathery glove) and that now, again, she is pregnant and the “space” she is shaping is the womb. But Plath’s words do not support this. Pregnancy is continuous not “nightly”. Carpentry is more suited to cupboards (or, indeed poems); and “the thing I am given” is a cold, unpleasant phrase with which to describe an unborn child. Those “two wet eyes and a screech” may be loved, but they are very different to the beautiful “moth-breath” and “handful of notes” of the child in ‘Morning Song’. And Plath was too good and too careful a poet to have chosen inappropriate words and images to describe a pregnancy.

If what the speaker here is carpentering nightly is this poem, and the half–moon has caused her to fill it with amputations, shadows, and the “two wet eyes and a screech” of the screech–owl, Lilith, what are we to make of the “white spit / Of indifference”?

I can only speculate. The half-moon is too well–formed to be called a “spit” of moon, but spit (or spittle) in folk–lore and superstition, embodies soul–power. The Devil’s spit causes despoliation and death; and humans spit to avert evil or to bring good fortune, but spitting for protection or for luck is hardly done indifferently. The evil Lilith, however, may well be indifferent to the harm she causes: this white spit may be hers, and the “dark fruits” which “revolve and fall ” may well be her deformed children. Perhaps, too, Plath had in mind the English folklore about blackberries, which belong to the Devil after Michaelmas Day, 29th September, because that was the day on which the Devil spat on them in a fit of temper when he fell from heaven into a thorny blackberry bush5. Plath had been delighted with the blackberries in her garden when the family first moved to Court Green, and her poem, 'Blackberrying', written in September 1961, was published in The New Yorker on 15 September 1962, just a few weeks before ‘Thalidomide’ was written6.

The sudden introduction of the cracked glass and mercury in the final three lines of the poem is a further confusion, unless one assumes that all that has gone before is hallucinatory, moon-induced images in the mirror of the mind.

It is widely assumed that the speaker in all the Ariel poems is Plath herself, and ‘Thalidomide’ does seem to express some of her fears about childbearing and, also, about writing deformed poems. But ‘Thalidomide’ is more than just a poem about that. Plath really does seem to conjure the dark moon goddess and her demons onto the page, and in the final three lines of the poem she effectively banishes her.

Three, as Plath would have known, is a powerful number in magic, and the line breaks dictate the three things which she decrees must happen. First, the glass is broken; next the image is isolated from it; and lastly, it is made to flee, its power is aborted and its poisons are dispersed “like dropped mercury”. Mercury from the back of a broken mirror cannot really do this, but the magical power of the poet’s imagination can ensure that it does.

Writing to Dr. Keith Sagar about the Ariel poems, Ted Hughes described a hypnotic technique which the notorious magician Aleister Crowley used to demonstrate. It involves, he wrote, “imitating somebody, exactly, until, at some imperceptible point, the initiative passes to you, and they begin to imitate you, and can then be controlled”. Hughes called this “the fundamental dynamics of the artistic process”, and he wrote that it was “nowhere so naked as in those Ariel poems”7. ‘Thalidomide’, in which at times it seems impossible to separate the speaker from the poet, certainly demonstrates this dynamic: but there is also a third presence in this poem, and both the speaker and the poet are very aware of this Moon–Goddess’s power.

‘The Applicant’ (dated 11 October 1962), which is the next poem in Plath’s original ordering of the Ariel manuscripts, occupies the position of The Emperor (card 4) in the circular Tarot journey. The Emperor is the ‘All Father’ and he, together with the Empress, transmits the creative energies into our world. His are the male generative energies, and these may be forceful and destructive, rational, passionless and cruel or beneficent, caring and just. He represents worldly power, the laws of society rather than the laws of nature, and, for the Tarot initiate he teaches the development of self-restraint, self-mastery, and the ability to balance rational powers with those of the instincts and emotions.

In Plath’s Tarot book, Rákóczi describes the Emperor as “the One who alone is allowed to part [the] veil” of his spouse. He is a threshold guardian, and through him the initiate will learn “the technique for awakening and using” their latent inner powers. These powers, which are “physical, astral, vital, desire, mental, spiritual and divine”, are used “under guidance” 8 but essentially they must be used in a carefully balanced way.

The speaker in ‘The Applicant’ is certainly a passionless threshold guardian and the wielder of considerable power. The applicant must be “our sort of person“, complete and natural, but there is no indication of what it is that he or she is seeking9.

With the Emperor in mind, what the applicant should be learning is to balance the often conflicting energies within themselves, to ‘marry’, so to speak, the male and female aspects of their personality. In Jungian terms, this would be described as integrating the male animus with the female anima in order to obtain psychological wholeness.

The marriages in this poem, however, are of a different kind. The speaker is not identified as either male or female, but because of our own social conditioning we tend to assume it is a man. He is derisory and patronizing towards the applicant. The initial questions about “rubber breasts” and other false body parts are faintly ludicrous and half suggests that the applicant is a woman, but he is called “my boy”; told, like a child, to “Stop crying”; and his insignificance, vulnerability and emptiness (‘empty’ is repeated three times) are all pointed out.

The marriages he is offered are caricatures of social conventions: a companion to hold his hand and offer tea and sympathy until, as in the marriage ceremony, death do them part; the role of a husband and decision–maker which is like a strait–jacket, stiff, black, funereal and indestructible; and a naked, malleable, “sweetie” – a “living doll”, who works, talks, does all the domestic duties and who, eventually, will be worth her weight in gold.

The poem is a superb ventriloquising of an authoritarian voice but the tone of irony which Plath imposes on it is unmistakable. It is a merciless satire of the Emperor and his authority, and of the conventions, laws and restrictions imposed by all such powerful male figures. Far from accepting the Tarot teachings here, she is openly and deliberately defiant. Just as she is in the other poem which she might have chosen to represent this card, ‘Daddy’. And it is interesting to note that according to the dates of composition included in the restored edition of Ariel, ‘Daddy‘ was written on 12 October 1962, just one day after ‘The Applicant’.

It might be argued that in writing these two poems Plath was displaying just the sort of marriage of reason and imagination that is required at this stage of the Tarot journey. What is missing, however, are the balancing energies of benevolence and love which are also an important part of the Emperor’s powers.

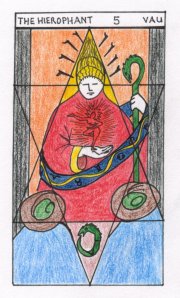

If Plath was using the Tarot journey as a framework for her Ariel poems, then ‘Barren Woman’ (dated 21 February 1961) represents The Hierophant, card 5.

The Hierophant, sometimes called the Pope or the High Priest, is a human being through whom divine energies are channelled into the world. He or she is a mediator, a shaman.

Plath’s barren woman is as empty as a hierophant should be and the word ‘empty’ is suitably emphasised as the capitalized first word of the poem. She is also “Nun–hearted” and “blind to the world” and, therefore, undisturbed by worldly things and in a suitable state in which to channel divine energies. But the imagery throughout the poem seems to have more to do with poetic stasis than with any divine responsibility.

Everything within the speaker is coldly architectural and archaic, the fountain (the only active thing in this “museum”) “leaps” but then “sinks back into itself”, as if all its creative flow is futile. A Hierophant might imagine having a great public in order to transmit divine energy to as many people as possible, but she (or he) does not imagine creating a winged victory like the goddess Nike (who was barren until she slept with her brother Osiris) or bald–eyed sun gods. Nor would the dead be of any importance or hindrance to her.

The speaker, however, imagines a great public associated with her creativity – with her mothering of a winged victory or, possibly, of poems (Apollo is the god of poetry). But she is so haunted by the dead that “nothing can happen”, and her muse, the moon, although sympathetic, is emotionless and “mum”. The word ‘mum’ suggests not only motherly attention, like the soothing of a feverish brow, but also dumbness: the moon offers the speaker no words and is “blank-faced” like an empty page.

Strangely, white Nike appears again in ‘The Other’ (dated 2 July 1962) but as a malign presence. And “bald–eyed” Apollos suggest offspring which lack – are bare of – the life–giving sun which, in ancient myth, is in the eye of Apollo. So, even the things which the poem’s speaker imagines mothering are not necessarily desirable.

Overall, neither in the imagery nor in the content is there much about this poem to identify it with a man or woman who, through intuitive wisdom, is able to transmit sacred, healing energies to our world, as the Hierophant does.

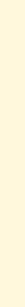

‘Lady Lazarus’ (dated 22-29 October 1962), which would be the next poem on the Tarot journey and, thus, would be linked with card 6, The Lovers, seems at first reading to be similarly remote from the occult meanings of the card.

Traditionally, this card is about choices associated with love. The initiate must learn to distinguish between love and lust, sacred and profane love, the promptings of the body and the needs of the spirit.

In ‘Lady Lazarus’, the speaker tells us from the beginning that she can die and be reborn. She has “done it” three times already. “I manage it”, she says, “One year in every ten”. It is “easy enough to stay put”, she tells us, but three times she has returned to life and, although there is dramatic exaggeration and irony in her tone, it is clear that it is rebirth which exhilarates her. The first time “was an accident”; the second time she meant to stay dead but responded to calls; “Number Three” is, because of the way she describes it, the most dramatic. She taunts her “enemy”, scorns the voyeuristic crowd which “shoves in” to watch her unveiling; and she warns of her phoenix–like nature.

The identity of her enemy is uncertain, and whether there was any choice in her third death and resurrection is unclear, but there is no love apparent in this poem.

One way in which a link might be made between ‘Lady Lazarus’ and The Lovers is to take what Rákóczi wrote about the relationship between the God of Love and Thanatos, the Greek god of death, and to extrapolate from that. Love figures on The Lovers card in the form of blind Cupid (Eros) with his bow and arrow but Rákóczi describes the God of Love incarnated by a Gypsy Master at this stage of the initiate’s journey as bearing “little resemblance to a cupid” but as “Eros and Thanatos in one”. I know of no other Tarot commentary which makes this connection, but although Thanatos (Death) may figure in Plath’s poem, there appears to be nothing to suggest that the speaker is choosing “the way of mind and spirit” in the face of the tests and trials set by this gypsy God of Love, trials which Rákóczi describes as similar to those of “Christ in the wilderness” of “Buddha being tested by Mara”10.

There are suggestions in the poem of the speaker’s rebirth being treated as a miracle, like the rebirth of Lazarus or, even, Christ. The witnesses want “a word or a touch”, or some sacred relic – blood, hair, a piece of her clothing. And the bringer of death is called ‘Lucifer’, a title commonly associated with Satan. But ‘Lucifer’ means ‘Light–bearer’ or ‘Morning Star’. In occult lore, Lucifer is a guide, not “Herr Enemy”, as Plath’s speaker calls him. And although the morning star is the star of Venus, there is nothing in the poem to do with Truth, Honour and Love, which Rákóczi tells us have been identified with the figures on The Lovers card.

Nor does there seem to be any suggestion in the poem that this is a spiritual rebirth in which the speaker rejects the body and bodily passions11. Instead, she celebrates her body: soon, she tells us, the flesh the grave “ate” will again be “at home” on her. Her derisory passion is obvious. After her third rebirth she is “the same identical woman”, and she vows that whatever fires she is subjected to she will rise again.

In ‘Barren Woman’ and ‘Lady Lazarus’ the connections between the poems and the associated cards are tenuous but possible. Yet, the Tarot seems to add nothing to our understanding of the poems: rather, it might be said that it adds unnecessary complications.

In spite of this, the order in which Plath chose to place these first seven poems does broadly reflect the initiate’s path as described by Rákóczi in The Painted Caravan. Plath has now dealt with the shaping elements of childhood – Mother, Father, Society, and the world around her. If she were an initiate, she would be said to have overcome and rid herself of all worldly influences and passions, emptied herself, and undergone a form of ‘death’. And she would now be ready to be reborn at the start of a new, even more testing, phase of spiritual growth.

Looked at in this way, the appearance of Lucifer as her enemy in ‘Lady Lazarus’ is interesting. Lucifer was a rebel angel. Aleister Crowley expresses this clearly in his poem, ‘Hymn to Lucifer’, which ends: “The Key of Joy is disobedience”: and in ‘Lady Lazarus’ Plath’s speaker is defiant and disobedient. She flouts death and she flouts conventions; she is argumentative, outrageous, blasphemous and, altogether, shockingly rebellious. In addition, it is interesting that Crowley sets out his poem as a dichotomy between Life and Death. “Without the climax of death, what savour hath life?” he asks; and his “sun–souled Lucifer”, through bringing death, gives life meaning, “Love and Knowledge”.

I am not suggesting that Plath necessarily knew or was influenced by Crowley’s work, although it is possible that she came across this poem in Ted Hughes’s books. But Crowley was expressing an occultist’s view of Lucifer, and with his poem in mind Lucifer can be linked to dichotomy, choice and love in Plath’s poem.

Herr Lucifer may be interpreted as the double–natured god Eros/Thanatos of the Gypsy Tarot Master. He is an alchemist who can change life. And the poem’s speaker is his Great Work, his “opus”, his a “pure gold baby”. Her repeated deaths and rebirths are like the alchemical dissolution and sublimation, purification by fire, destruction of “flesh” and “bone”, from which she rises “out of the ash” like the alchemical phoenix12. And, in the face of a Life/Death choice, Plath’s speaker has defiantly chosen both. She, like all who undertake a spiritual quest, is prepared to die, to become “nothing”, and to be reincarnated. But she warns that this new incarnation will be fiery and fierce (as one might expect a child of Lucifer to be) and she vows that (like him) she “will eat men like air”.

Unfortunately, this final bold claim smacks of hubris and suggests that if the she is an initiate on a quest for spiritual wholeness then she still has much to learn. In spite of this, the next poem, ‘Tulips’ presents a picture which makes her proud, defiant claims seem like bravado.

REFERENCES AND NOTES (1)

1. Hughes, T. ‘Collecting Sylvia plath’, Winter Pollen, p.172.

2.“Plath crossed out the word ‘Mum” in her first version of the title, ‘Mum:Medusa’(‘Medusa’ MSS, folder 1, sheet 1.)”. De Nervaux, L. ‘The Freudian Muse: Psychoanalysis and the Problems of Self-Revelation in Sylvia Plath’s “Daddy” and “Medusa”’, E-rea, 5.1, 2007. p.18.

3. Hughes, T. ‘Publishing Sylvia Plath’, Winter Pollen, p.165.

4. Hughes, T. ‘Collecting Sylvia Plath’, Winter Pollen, p.172.

5. Brain, T. ‘Unstable Manuscripts: The Indeterminacy of the Plath Canon’, in Helle, A. (ed.) The Unraveling Archive: Essays on Sylvia Plath, University of Michigan Press, 2007. pp.17-37. My thanks to Carol Bere, a Hughes scholar with extensive knowledge of Plath scholarship, for alerting me to this paper, which she rightly calls “provocative”.

6. Hughes, T, ‘Sylvia Plath and her Journals’, Winter Pollen, pp. 180-190.

REFERENCES AND NOTES (2)

1. Rákóczi, The Painted Caravan, pp.33-4.

2. Kukil, K (ed.), The Journals of Sylvia Plath, 29 March 1958. p.355.

3. Thalidomide was prescribed as a sedative and, especially, for morning-sickness in pregnancy. From 1958 to1961 when the drug was withdrawn, about 2,000 children with terrible birth–defects caused by Thalidomide were born in the UK. Many died within a few months but some are still living.

4. Anansi the trickster spider man of Plath’s poem ‘Spider’ comes to mind. Sylvia Plath: Collected Poems, Faber, 1981, p.48-9. So, too, does Arachne, the mortal who, in Greek mythology, was turned into a spider by the Goddess Athena.

5. Blackberries, in any case, are generally spoiled, grey and maggoty by the end September.

6. Plath,A. (ed.) Sylvia Plath: Letters Home, 4. Sept. 1961 and 12 October 1962. pp. 428 and 466.

7. Reid, C. (ed.), Letters of Ted Hughes, Faber, 2007. Hughes to Sagar, 23 May 1981. pp.444-5.

8. Rákóczi, The Painted Caravan, p.35.

9. Plath spoke of the speaker as “an executive, a sort of exacting super-salesman” who wants to be sure that “the applicant for this marvellous product really needs it and will treat it right”. Notes: 1962, Sylvia Plath:Collected Poems, p.293.

10. Rákóczi, The Painted Caravan, p.38.

11. Plath spoke of the woman as “the Pheonix, the libertarian spirit, what you will”, but also as “just a good plain, very resourceful woman”. Notes: 1962, Sylvia Plath: Collected Poems, p.294.

12. In Alchemy, the chemical process of changing lead into gold (the ‘Great Work’) is also a metaphor for the transmutation of the base matter of a human nature into pure spiritual gold. The phoenix is a symbol of the ‘rubedo’, the fiery reddening which signals the completion of that process. Ted Hughes’s careful use of alchemy as a framework for Cave Birds: An Alchemical Cave Drama (Faber, 1978) is examined in detail in my book: Ted Hughes: The Poetic Quest.