It is true that I am best known as a Ted Hughes scholar and I have published widely on his work, including studies of his use of the occult1, but the poetic interaction between Hughes and Plath was so close that it is impossible to study Hughes’ work without also becoming very familiar with Plath’s. So, I was very interested to read Julia Gordon-Bramer’s papers on her study of Plath’s use of Tarot in her original ordering of the Ariel manuscripts2.

In one paper, she writes that “the oevre of both Sylvia Plath’s and Ted Hughes’s poetry, fiction and essays is entirely structured upon Alchemy and a Tarot template – based on the ancient Qabalah”. She goes on to say that “every book by each of them, beginning with Hughes’ Hawk in the Rain and Plath’s Colossus, were written under this mystical ordering and symbolism, and with enough success that the templates would structure every bit of work each of them wrote throughout their respective lives”.

With regard to Cabbala, in particular, this is not true for Hughes, and I doubt that it was true for Plath, who as late as November 1959 was still vowing, in her journal, to learn astrology and Tarot3.

Hughes, from an early age was fascinated by the poetry of W.B.Yeats and especially by Yeats’ study of magic and his involvement with the Esoteric Order of the Golden Dawn. Following in Yeats’ magic footsteps, Hughes read widely in ancient books of magic and gained a broad understanding of Tarot and of the NeoPlatonic/Christian interpretation of sacred Jewish Cabbala4. However, Hughes’ first serious use of Cabbala (but not Tarot) was in the poetic sequence Adam and the Sacred Nine, which was published as a limited edition book in 19795. He did not use Cabbala or Tarot again as a framework for a sequence of poems until the creation of Birthday Letters, in which he used both with extraordinary care and with a deep understanding of the energies involved6.

I have found no such structured use of Cabbala in Plath’s work, although there is plenty of evidence for her use of Tarot imagery in her late poetry.

Tarot is certainly used as a mnemonic memory aid by some, but certainly not by all, Cabbalists. However, Tarot and Cabbala can each be used quite separately, and Tarot is frequently used for divination and fortune-telling by people who know nothing about Cabbala. Tarot can also be used, as Plath seems to have used it, for meditation and inspiration. In her journal entry for 9 February 1958, whilst still vowing to learn Tarot, she contemplated working herself into “mystic and clairvoyant trances to get to know Beacon Hill, Boston, & get its fabric into words”. And Hughes certainly believed in her clairvoyant abilities (which he called her “internal crystal ball”7) and he believed that these were in evidence long before she made those entries about learning Tarot in her journal.

It seems likely that Plath was first introduced to a version of the Tarot by her grandmother, Aurelia Greenwood Schober, who taught her to play the popular Austrian card–game of Tarok8, a ‘trick’–taking game which can be played with an ordinary pack of cards. The picture cards are used in this game as trumps but no significance is placed on their imagery or symbolism. Later, Plath owned her own Tarot pack. The Marseille deck was given to her by Hughes for her twenty–sixth birthday (SP Letters 18.10.56). She had also bought a copy of The Painted Caravan: a penetration into the secrets of the Tarot cards, by Basil Ivan Rákóczi which was published in 19549. Her copy, held in the Smith College library archive is inscribed “Sylvia Plath, London – 1956”. In a letter Hughes on October 16th 1956, she wrote:

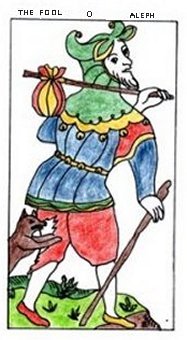

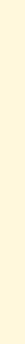

I began reading my Painted Caravan book; it is my favourite book;…. I meditate on the Fool and the Juggler, staring at the pictures, reading and re–reading the lucid, pleasantly written descriptions of them and their significance. I shall go through the whole book slowly this way, so that I shall come upon the difficulties of setting out the Pack with a basic sense, at least, which will flow and re–cross and blend, I think, by great concentration and much practice.

In that book, Rákóczi claims that the basic concepts of all the different religions of the world are to be found in the symbolism of the cards. One can assume, therefore, that, as is the case with most religions and with any secret and potentially dangerous knowledge, an initiate must follow a prescribed ‘path’ in order to gain mastery of that knowledge. The twenty–two cards of the Major Arcana of the Tarot, when arranged continuously by number in a circle or a figure–of–eight, describe the steps to be taken by an initiate on such a path; and it is usual for the path to be completed a number of times in a lifetime before mastery can be achieved.

My purpose, here, is to investigate whether or not Plath used the Tarot as just such an initiatory journey in Ariel, taking the twenty–two cards of the Major Arcana as her guide. And if not, just how the Tarot imagery which is present in the poems might add to an understanding of the poems.

For a number of reasons, I am not convinced by Julia Gordon–Bramer’s analysis of the links between particular Ariel poems and specific cards of the Major and Minor Arcana, especially as she assumes that Plath used the Rider–Waite deck, not the Marseille deck which Plath is known to have owned. The meaning of the cards is the same, but the images are very different, and some of Gordon–Bramer’s analyses rely on the images.

In her analysis, some poems (e.g. ‘Barren Woman’, ‘Death & Co’, ‘Poppies in October’) are said to reflect the imagery and symbols on a card. However, they do not always reflect the deeper occult meaning which the Tarot gives these symbols. Some poems (e.g.‘Thalidomide’, ‘The Jailor’, ‘Ariel’ and ‘‘Lesbos’), are interpreted as representing the card (and therefore the occult meaning of the card) reversed. This is understandable if the poems show negative energies being confronted and overcome, as would be the goal in an initiatory journey, but this is not always the case in the Ariel poems.

Other links made between a particular poem and a specific card are tenuous and not adequately supported with evidence. I know of no precedent, for example, for claiming that nine Major Arcana cards of the Rider–Waite deck (which Julia Gordon–Bramer assumes Sylvia used10) include mountains in their pictures and that these mountains represent Abiegnus, the Sacred Mountain of Initiation of the Rosicrucians11. She suggests that this is the source of “nine black Alps” in ‘The Couriers’. But Plath’s nine black Alps (note the capital ‘A’) could equally be the nine Bernese Alps over 4,000m which are widely known in Europe as important mountaineering objectives. These peaks, the steep slopes of which are black and snow–free, are in Switzerland, but the eastern part of the Alps extends into neighbouring Austria and Plath could well have heard of these peaks from her Austrian grandparents.

Both the above suggested interpretations of the nine black Alps are conjectural but this does not negate Julia Gordon–Bramer’s interpretation of Plath’s Alps as a symbol of initiation. Yet, what sort of initiation are we talking about and how does this interpretation help us to understand the poem?

And if Plath did use the Tarot to order her Ariel poems, why did she do that?

Was she seeking the spiritual and psychic death and rebirth that is the usual purpose of such a quest? Ted Hughes certainly believed that Plath’s writing was driven by the sort of inner, psychological process which “a Jungian might call…a classic case of the alchemical individuation of self”; and that it was a continuous, inner, healing process of death, regeneration and rebirth12.

Or was she seeking divinatory and occult powers: “the highest philosophy known to the wise and the darkest arts known to the black magician”, which Rákóczi claims are part of the ancient wisdom “held under veils” that only a Gypsy Master of the cards can penetrate?13

Was she seeking to climb those initiatory peaks in order to achieve success in her writing?

Or, was she simply using individual cards as a source of inspiration as she threw off her old life and began a new one and, because the Tarot symbolism has universal archetypal meaning, they could later be arranged to fit the circular pattern of a Tarot quest? The poems were not, after all, written in the order in which she arranged the manuscripts. And Frieda Hughes, in her Foreword to Ariel: The Restored Edition, writes that Plath “last worked on the manuscripts’ arrangement in mid–November 1962”14, which suggest that, as with her other books, Plath rearranged the order of the poems several times.

I intend to work though the Ariel poems as they are ordered in the Restored Edition, and to compare each poem with the card to which it would be linked in an initiatory Tarot journey. My description of the cards and their traditional meanings will be as brief as possible. And, since this is work in progress, I expect my understanding of Plath’s use of the Tarot to change and develop as I go along.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

‘Morning Song’ (dated 19 Feb. 1961)15 is the perfect poem with which to start a sequence of poems that celebrate the birth of a new voice “among the elements”: it could be the child’s voice or Plath’s Ariel voice or both. This ‘song’ prefaces the “handful of notes” which are Plath’s Ariel poems and celebrates, too, what for Plath and for the child in the poem is a new life, a new journey, a potentially dangerous step into the unknown future. All of which also makes it a perfect poem for the path of the Tarot Fool, who is depicted as the questing, naive initiate stepping blindly off at the start of his journey, his old life stuffed into a bundle and slung behind him on a stick over his shoulder, and the dog of materialism snapping at his heels.

The rounded vowel sounds in the text of the poem; the child’s “One cry”; the fat gold watch which marks the continuous, circular pattern of time; the naked, flickering, “moth-breath” fragility of the new life, which shadows the lives of the parent(s) with unknown dangers and will, in Nature’s endless cycle of death and regeneration, eventually replace them; the balloons which rise into the air at the end of the poem; and the “Love” with which it begins; all these are exactly right for the scene and the emotions which Plath describes. They also embody the endless circle, the roundness, the zero which is the number of the Fool’s card16.

‘The Couriers’, however, (dated 4 Nov. 1962) which is the second poem in Plath’s ordering of Ariel and, thus, the second step of the initiatory Tarot journey, does not fit the occult meaning of the matching Tarot card as closely, although at a surface level there do seem to be many connections. Like the ‘The Juggler’ which is sometimes the name of the figure depicted on this Tarot card, ‘The Couriers’ is tricky. The ‘voice’ is strong but the imagery and meaning is not easy to interpret. We are told not to accept various things, each of which seems to be an example of corruption or deception: a snail on a leaf will eat it; Acetic Acid (vinegar) spoils if it is kept in a tin; a gold ring may seem to embody the sun, or true love, but it is only a symbol of these things. The cauldron of the sun seems to be mad and impotent, unable to melt the “frost on the leaf” or to green the black Alps without the help of Nature. Reality reflected in a mirror is disturbed and cannot be trusted: and the mirror of the sea, like the subconscious, is “grey”, unclear, and easily shatters itself. Love, too, is a ‘season’, which means it must change, but we are left uncertain as to whether the speaker knows this and boldly chooses to live only in this season or is ironically declaring that he or she has failed to understand that love cannot last17.

All this trickery and deception is appropriate to the Juggler and it reflects one side of the double nature of the trickster god, Hermes, who is linked by Rákóczi to this card. Is the speaker perhaps Hermes himself: arrogant and self-satisfied? If so, the poem neglects the other, more valuable, side of Hermes’ nature, for Hermes is the messenger of the gods, and guide to the soul. He invented music, the alphabet and mathematics and is the inspirer of eloquence. He is the Magus, the Magician and the Gypsy Master, all of which are other names for this card. And he, as Hermes/Thoth, is credited with the invention of the Tarot.

The Magus/Magician, according to Rákóczi, symbolizes creative energy, the development of latent powers and the ability to face risks. In other interpretations, the number of the card, which is 1, indicates that the Magus carries the spark from the Divine Creative Source. He may be tricky and devious but he is a most knowledgeable wielder of occult powers, a guide to those powers within us, and a link between us and the original creative energies. For the initiate, he represents the first stage of self-awareness: the first awareness of the need to balance the inner and the outer worlds in order to tap the creative energies within. None of this seems evident in ‘The Couriers’.

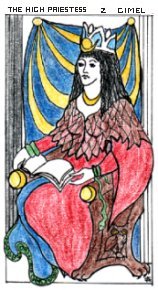

‘The Rabbit Catcher’ (dated 21 May 1962) should reflect the third Tarot card, the High Priestess, who is also known as Pope Joan, Juno, The Wise Woman and The Gypsy Witch. In many Tarot decks, as in the picture in The Painted Caravan, she is shown enthroned between two pillars (sometimes labelled Justice and Mercy) and behind her is the veil which hides the secret knowledge. She is the Queen of Heaven, Moon Goddess, oracular sibyl, the passive channel between the physical and the spiritual energies, and the mediator of the energies of creation and destruction. She links the conscious and unconscious mind and, according to Rákóczi, she represents our choices and desires, the Jungian anima, and the awakening and maturing of instinct. For the Initiate, she is the Gypsy Master of Initiation who may or may not open the way to the secret knowledge. Rákóczi also describes her as both evil Hecate and beneficent Isis18.

Julia Gordon-Bramer gives the meaning of the High Priestess card as “a powerful woman with no need of men”; and ‘The Rabbit Catcher’ is one of the poems which she suggests reflects the card’s picture and images. But the woman in this poem is not all–powerful. She describes her feelings of vulnerability in this “place of force”. The elements have attacked her, torn at her, gagged her, blinded her with light. The sea seems oily with death, the plants malign, even the tiny flame–like gorse flowers are “yellow candle-flowers” which remind her of the formal rituals of death – they are “efficient”; their beauty “extravagant, like torture”.

It might be argued that the poem reflects the powers of the High Priestess as Hecate, Queen of the Underworld. That it is she who is channelling these forces into this woman’s world, testing her initiate or showing her that the easy, perfumed path leads only to snares, nothingness and more deaths. But the death-dealer in the poem is male. And he is not just a channel for the energies, he is joined to the woman by “tight wires”.

Taking a cue from Rákóczi’s description of the High Priestess, and knowing of Plath’s interest in Jungian psychology, one might suggest that the woman in the poem represents the Jungian anima, the female element in the personality, freeing itself from a dominant and dominating male element of the personality, the animus, which would otherwise prevent the her from continuing on the initiatory path. This seems to me, however, to be an imposed and far–fetched interpretation.

None of these interpretations add anything to the poem which is in itself a powerful, skilfully crafted expression of emotional turmoil and distress. A much more likely interpretation is that Plath has adopted the role of the High Priestess. The force, the snares, the excitement, the “little deaths”, all belong to the rabbit catcher himself but also to the poet, who is channelling the energies into the poem as the Moon Goddess, Hecate, Queen of the Underworld. Hughes, in his response to this poem in Birthday Letters, identified the “dybbuk furies”, the “Moon’s blade”, and the way this poem, like others in Ariel, “came alive” in Plath’s hands “like smoking entrails”19. Here is Hecate’s witchcraft. And here in this poem is Plath’s precarious and masterly balance between poet and poem, reality and imagination. No wonder ‘The Rabbit Catcher’ was one of the titles she considered for the Ariel sequence.

Again, however, we are seeing only one aspect of the Tarot card: only the evil face of Hecate, rather than the beneficent face of Isis. An initiate, or even an Adept or Master, would seek to engage with every aspect of the High Priestess.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

1. My detailed investigation of Hughes’ use of Alchemy in his work was published in my book, Ted Hughes: The Poetic Quest, University of New England, Armidale, 1994.

2. Gordon-Bramer, J. ‘Sylvia Plath’s spell on Ariel’, Plath Profiles, Vol.3, Indiana University, 2010. pp.90-99.; ‘As we like it: Ariel’s Forewords’, Plath Profiles, Vol. 5. Indiana University, 2012. pp.216-63. ‘“Fever 103º”: the Fall of Man...’, Plath Profiles, Vol. 4, Indiana University, 2011. pp.88-105.

3. Kukil, K (Ed.) Entry for 7 Nov 1959, The Journals of Sylvia Plath, Faber, 2000. pp.525. See also the entries for 9 Feb. 1958, p.327; 13 Oct. 1959, p. 517; and 4 Nov. 1959, p.523.

4. The NeoPlatonic/Christian Cabbala was developed and taught by Renaissance scholars such as Marsilo Ficino, Pico della Mirandola, and Giordano Bruno. Bruno was in England from 1583-85. Shakespeare possibly met him and certainly heard of his teachings. Hughes writes about Shakespeare’s use of NeoPlatonic Cabbala in Shakespeare and the Goddess of Complete Being, Faber, 1992.

5. Hughes, T. Adam and the Sacred Nine, Rainbow Press, London, 1979. The press was established and owned by Hughes and his sister Olwyn. My analysis of Hughes’ use of Cabbala in this sequence, Adam and the Sacred Nine: A Cabbalistic Drama, can be found on my webpages at ann.skea.com/THHome.htm.

6. My detailed analysis of Hughes’ use of Cabbala and Tarot in Birthday Letters, Howls & Whispers and Capriccio is available as Poetry and Magic on my web pages at ann.skea.com/THHome.htm.

7. Hughes, T. ‘Sylvia Plath and her Journals’, Winter Pollen, Faber, 1994, p. 184.

8. Anne Stevenson, in her biography of Plath, Bitter Fame, records Olwyn Hughes’ memory of Plath teaching the Hughes family to play this game. (Bitter Fame, Viking, 1989. p.178).

9. Rákóczi, B.I. The Painted Caravan, Boucher, The Hague, 1954. Plath’s copy of this book is held in the Neilson Library Sylvia Plath archive at Smith College.

10. In her article ‘Sylvia Plath’s spell on Ariel’ (Plath Profiles, Vol 3, 2010, pp.91-2) Julia Gordon-Bramer suggests that Plath used either the Rider–Waite or the Tarot de Marseille deck. In her second article, ‘As we like it’ (Plath Profiles, Vo.5, 1012, p.219) she specifies the Rider–Waite deck as the one Plath “relied on” but she gives no reference to support this information.

11. It is difficult to determine exactly how many mountains are shown on the Major Arcana cards of the Rider-Waite pack. Some cards show more than one mountain, others show multiple peaks. The traditional Tarot de Marseille Tarot packs do not show steep mountains at all, just green ground and hillocks.

12. Hughes, T. ‘Sylvia Plath and her Journals’, Winter Pollen, Faber, 1994, pp.180-2.

13. Rákóczi, B.I. The Painted Caravan,p.15.

14. Plath, S. Ariel: The Restored Edition, Faber, 2007, p.xi.

15. I am using the established dates listed by David Semanki in the Notes to Ariel: the Restored Edition, pp.208-9.

16. ‘Love’ in tennis represents 0.

17. It may be purely coincidence, but 'Love is a Season', sung by Eydie Gormé, was part of an LP record released in 1958 and the song was frequently broadcast on the B.B.C.

18. Rákóczi, The Painted Caravan, pp.30-31.

19. Hughes, T. ‘The Rabbit Catcher’, Birthday Letters, Faber, 1998, pp.144-6.