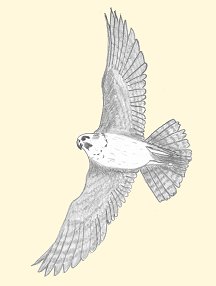

‘And the Falcon came’ (THCP 445)

Falcons are one of the smallest of the great eagles, and for centuries they have been captured and trained by humans for hunting purposes. They are powerful birds; swift and deadly hunters, which soar effortlessly high in the heavens and seem to drop from the sun onto their prey. Their golden eyes, like the “round angelic eye” of Ted’s hawk in ‘The Hawk in the Rain’ (THCP 19), resemble the sun’s orb, and in many countries they are still regarded as sacred birds and as offspring, like the Egyptian falcon-god, Horus, of the great Sun God. They are associated, too, with goddesses. Circe, in her falcon form, is related to Helios, the Sun; Freya hovers over the Earth in falcon garments; the Great Goddess, Frigg, is also a falcon. All – gods and goddesses – are able to move with ease between heaven and earth; all represent nobility, power and fertility.

In Cabbala, the first ‘offspring’ (so-to-speak) of the Divine Source is the emanation of pure white light which appears at Kether, the Sephira at the Crown of the Cabbalistic Tree in the topmost World of Atziluth. This is where, in Alchemical and Cabbalistic symbolism and imagery, the great eagle /sun-bird resides. In our material world of Assiah, however, where we receive only reflected light from the upper Worlds, it is appropriate that the first angelic messenger to appear to Adam should be the symbolic Falcon (the word is capitalized throughout the poem) but also just an ordinary bird. This Falcon is very like Ted’s hawk in Hawk in the Rain, and it is remarkable that in the very first poem of Ted’s first published book his protagonist drowns “in the drumming ploughland” whilst the hawk hangs “effortlessly at height” holding “all creation in a weightless quiet”. Adam and the hawk were there in Ted’s work from the start, but Ted’s language and ‘voice’ in ‘And the Falcon came’ is simpler and more direct than it was in his earlier poem. His Falcon is mineral hard, his “gunmetal feathers”, his “bullet-brow”, his deadly talons and his “tooled bill” have one purpose only, and that is “the reconstruction of Falcon”. It is entirely consistent with this Falcon’s position at Kether, Sephira 1, which is titled ‘Unity’ and which, in Hebrew Cabbala, is given the God-name EHEIEH – (translated as ‘I am’ or ‘I will be’) – that this bird has but a single purpose from which he will “not falter”.

“The gods of Kether” says one Cabbalistic text, “are terrible gods which eat their children” And Kether is “pure being unlimited by form or matter”19. This applies perfectly to Ted’s Falcon as a reflection of that Atziluthic pure being. He is ruthless and powerful, “dividing the mountain”, “hurling the world away”, bent on “collision” and destruction. He grasps “complete” in his talons the “crux of rays” which, in Cabbala, symbolize the power of Kether to cross-link all polarities in order to create unity, and which also suggests the lightning flash of energy from the first emanation which zig-zags down the Tree from Sephira to Sephira, connecting heaven and earth.

And, since Kether is the Sephira from which all comes and to which all must return, this falcon holds in its talons “a first, last single blow”.

Ted’s poem, however, also describes a real bird and the normal, familiar hunting behaviour of this bird. So, throughout the poem, the Cabbalistic energies of this Angelic guide from the Worlds above the World of Assiah, are reflected in the real behaviour of a real bird. It ”plucks out the ghost”, which is the life of its prey, and strips down this dead creature “to its component parts”. The “ghost” – that immaterial spark of life – is the spark of Divine Spirit which is to be reunited with the Divine Source; and the “hot flutter of earth” is not just a vivid image of fear, hot blood, and flying fur and feathers, it suggests, also, the fluttering presence of the hot, fecund, female Spirit of Nature.

This Falcon, in which all things are united, comes to Adam to demonstrate to him and teach him single-minded action, ruthless will, and determination to get to the heart of anything he tackles. It demonstrates, too, the ability to find the essence of earthly life and unite it with the pure “eye-flame” – the fiery, explosive energy – of the heavenly Source.

‘The Skylark came' (THCP 445-6)

The next birds to appear to Adam is the Skylark “who labours the whole day singing”20. As the second bird and the second Angelic messenger, it is associated with Sephira 2, Chokmah (Wisdom, Creativity). At Chokmah, the first division of Kether’s pure energy takes place and, with duality, unity and stable equilibrium is lost.

Chokmah, in Cabbala, is known as ‘All Father’, the fertilizing Male Principle of the Cabbalistic Tree, but Chokmah is the place where male/female duality, like all other dualities, begins. It is here that the Female Principle of God becomes separated from the Male Principle, to eventually become exiled in matter, constantly seeking reunion. In the highest, Atziluthic World of Emanations, where the energies are still unbounded by form, unlimited, endlessly potent and dynamic, the Female Principle (Nature) is still pure vibration.

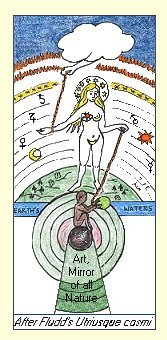

The reflection of this in the material World of Assiah is the Hermetic NeoPlatonic image of her as Sophia, Goddess of Wisdom and, in common Cabbalistic imagery, it is her ladder of knowledge and creativity which, as in Ted’s poem, is the “swinging ladder” which is “hooked to the sun” and connects heaven and earth. This is the Biblical Jacob’s ladder, which appeared as Jacob (like Adam) lay on the earth and dreamed. On this ladder Jacob saw “the angels of God ascending and descending” (Genesis 28:12-13), just as Ted’s divine birds visit Adam and leave. Sophia’s ladder is also the golden chain by which, as the Hebrew Zohar says, “Everything is connected with everything, right through to the nethermost end of all the links”21 or, as Robert Fludd drew it in 1617, “leads from the hand of God via Virgin Nature” to the Earth, where “man imitates Nature and seeks to improve it”22. By means of this ladder or chain, we can climb, with Nature’s help, out of the darkness of ignorance into the Divine light.

In Adam and the Sacred Nine, Nature’s song and her constant labour for reunion with the male Principle, is reflected in the Skylark, which is her emissary. It, like the Archangel of Chokmah, Ratziel, is ‘Herald of the Deity’ and herald of the dawn of enlightenment. Early-rising country-folk are still said to ‘get up with the lark’, which is known as ‘the bird of dawn‘. Its crested head, too, associates it with other crested birds like the cockerel and the hoopoe, both of which are regarded in myth and folk-lore as divine messengers and heralds of a new day and a new beginning.

Skylarks sing constantly as they fly and their song is one of the most persistent and noticeable summer sounds of the English countryside, still clearly to be heard when the bird itself is no more than a tiny speck far up in the heavens. Their flight, too, is effortful and distinctive: their wings are constantly in motion and only stop (with their song) when they plummet back to earth and the grass in which they nest. The lift and fall of the Skylark’s flight, and the heights to which it climbs, singing, as if “to thatch the sun” with bird-joy (a useless endeavour, to erect a frail and worldly roof over the immense and powerful cosmic energies of the sun), all this is beautifully captured in Ted’s poem.

The unpunctuated lines flow together like the continuous bird-song, and the repetitions – “with its song”, “with its labour”, “with its crest” and again, “with its song” – emphasise and enclose the bird’s form and labour within that song, so that all are physically linked in the poem, just as all reflect its Divine origins and allegiances.

With its song – that fragment of the Divine creative energies – the bird labours to keep off the “rains of weariness" and the “snows of extinction”. With its crest – that physical heraldic emblem of its status as a messenger of the Divine – it seeks to crown both sun and earth. Being mortal, its flight to the sun can only fail: no matter how hard it labours to lift itself, its crest and its song, above the sun, it “can only fall”. Being mortal, it can never achieve its ultimate aim – it can never crown Earth (Nature) and Sun with its crest so that they are married together, as are the conjoined Queen and King of Alchemical and Cabbalistic imagery. Its labours are “useless excess”, yet it does not give up. And “meanwhile” it wears the crest itself as a symbol of its Divine purpose.

The Virtue of Chokmah is Devotion. And this is what the Skylark demonstrates and what it comes to teach Adam. Only by constant, devoted effort can he lift himself towards enlightenment. He will fall again and again in the unbalanced energies of our world, but only by determination and dedication can he help to re-establish the equilibrium and unity which can hold back the darkness23.

‘The Wild Duck’ (THCP 446)

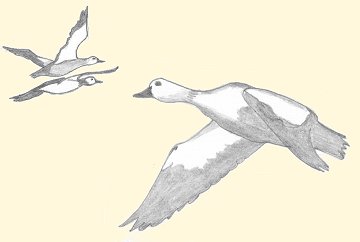

The Wild Duck, the third bird to visit Adam, comes as the Angelic messenger from Sephira 3, Binah (Truth, Understanding). Binah is known as ‘All Mother’. She, like Chokmah, represents the Female aspect of God, but her energies are no longer the dynamic polarities of Chokmah. Her number, 3, indicates that she is the third, stabilizing element, of what is known in Cabbala as ‘The Supernal Triangle’ of Sephirothic emanations at the top of the Cabbalistic Tree.

Binah is ‘Mara’, the ‘Bitter Sea’. Her Element, like that of the wild duck, is Water; and her Archangel is Tzaphkiel, ‘Beholder’ or ‘Eye of God’. She has no form, but she is the ‘Mother of Form’, the ‘Womb of Matter’, the egg from which all life comes. And with life comes death, when the Spirit returns to her. She is the origin of life and death, the serpent eating its tail, the Uroborus, and we know her as Nature, the Great Goddess, the Triple Goddess and all the Mother goddesses of our mythologies. At Binah, everything is potential. Nature is not yet imprisoned in matter but at Binah – the Mother of Form – this is imminent.

Ted’s wild duck is female and she embodies many of the aspects of Binah. In

myth, folk-lore and legend, the wild duck is associated with the Waters of Eternity,

with Isis, with wisdom and with fertility, and her image is found in the ancient art

and artefacts of many nations. Her ‘Mother Element’ is water: this is where

she breeds, nests and brings up her young.  But she is equally at home in the air and on land; and, every Autumn,

attuned to the Sun’s cyclical pattern around the Earth, she flies from her Arctic

home towards the warmer lands where, with her lifelong mate, she will feed, make her

nest and bring her ducklings to adulthood. The sight of flocks of wild ducks returning

faithfully year after year to their old nesting sites, is a seasonal marker noted by

farmers and hunters alike, and the wild duck is a familiar, friendly part of the

domestic lives of British people – more so, for most people, than

the wild goose or the swan, both of which are traditionally associated with gods and

goddesses. Nevertheless, because she is attuned to the natural cycles; because of her

faithful behaviour and her devoted protection of her brood; and because she lives

comfortably in all four Elements, the wild duck, like the goose and the swan, has

special symbolic status.

But she is equally at home in the air and on land; and, every Autumn,

attuned to the Sun’s cyclical pattern around the Earth, she flies from her Arctic

home towards the warmer lands where, with her lifelong mate, she will feed, make her

nest and bring her ducklings to adulthood. The sight of flocks of wild ducks returning

faithfully year after year to their old nesting sites, is a seasonal marker noted by

farmers and hunters alike, and the wild duck is a familiar, friendly part of the

domestic lives of British people – more so, for most people, than

the wild goose or the swan, both of which are traditionally associated with gods and

goddesses. Nevertheless, because she is attuned to the natural cycles; because of her

faithful behaviour and her devoted protection of her brood; and because she lives

comfortably in all four Elements, the wild duck, like the goose and the swan, has

special symbolic status.

Ted’s wild duck flies, as wild ducks do each Autumn, from the “swaddling” snows of the Arctic. But what is this “tower of the North Wind” from which she comes?

North is an important direction for Cabbalists for many reasons. It is traditional

home of the gods, not just in Northern mythologies but also in Biblical lore. Robert

Graves wrote that Jehovah, before he became a transcendent God, “lived like

Boreas in the mountain to the far north”24. And for

NeoPlatonic Hermeticists and Cabbalists, the Pole Star, Polaris, is the throne of the

Supreme Deity, and is known as the ‘Eye of Heaven’, the ‘World

Axis’25. North,

therefore, is the most powerful of directions: it is the location of the Divine

creative energies, the source of Otherworldly powers, and the place of magic. Ted used

its magic in ‘Amulet’ (THCP 260), which is the very first poem in

Under the North Star26. And, in

the circling shape of that poem, and in the wolf in particular, he embedded the

circling life/death energies of Binah:

Inside the Wolf’s eye, the North Star.

Inside the North Star, the Wolf’s fang.

In ‘The Wild Duck’, Ted’s “tower of the North Wind” finds particular parallels in Greek mythology, where the North Wind is Boreas, and his crown is the small star constellation Corona Borealis in the Northern sky. This constellation is known in Celtic lore as ‘Caer Arianrhod’, the Castle of Arianrhod, and she is the White Goddess whose titles, ‘Life in Death – Death in Life’27 exactly describe the circling, form-making, form-destroying energies of Binah. So, the wild duck which visits Adam “pitched from the tower” of the Goddesses castle, and Ted beautifully combines Arianrhod and Boreas in imagery of the duck’s mother and father. Her mother’s “shawl of stars”, suggests Arianrhod’s star-goddess status and the constellation of stars which represent her castle. And the duck’s father, with “the black wind in his beard of stars”, is black as Boreas, who is associated with Saturn, the dark skies of winter and with death.

Ted’s poem, ‘The Wild Duck’ is, like the creature itself, steeped in mythology, and there are yet more ancient mythological associations in the “fracturing egg-zero” from which the wild duck is hatched. It’s shape is the circle of eternity – the beginning and the end linked together like the Uroborus, the snake that eats its tail. It is also the egg-zero of Binah, who fractures the emptiness of space with created form. And it is the Orphic Egg – the silver egg created by the Wind and Black-Winged Night and laid in the Womb of Darkness at the beginning of time28. These myths are echoed in Ted’s poem as the duck gets up “out of the ooze before dawn” just as “the earth gets up out of the frosty dark”. Exactly at sunrise, when the first “precarious crack of light” is reflected from the “dew” on the earth, she “hangs” momentarily, as if between the two halves of the fractured Orphic Egg: “between earth glitter and heaven glitter”. Then she flies “through the precarious crack of light” to bring her message to Adam. Both she and the Earth, in Ted’s poem, come from “the frosty dark at the back of the Pole Star”, as if from the darkness and emptiness in which Binah first gave the disparate energies form and, so, created our material universe. Polaris, the North Star, is known as the Axle of the World, the hub of the wheel around which the starry heavens, the fabric of our universe, revolves. That it is also known as ‘the Eye of Heaven’, suggests, too, the duck’s connection with the Archangel of Binah, Tzaphkiel, whose title is ‘Eye of God’.

The duck comes to Adam “Quacking Wake Wake”. What she wants him to do is follow her example: to get himself up out of the ooze of mud, break through that egg of silence and ignorance in which he lies, and fly through the crack he makes, however precarious it may be, towards the warmth of the Sun, which is the only source of life and light. In other words, he must break the ice of inertia in which he has swaddled himself and make the first precarious move towards enlightenment and hope.

‘The Swift comes the swift’ (THCP 447)

The swift is the fourth sacred “instructor” to visit Adam and, so, is associated with Sephira 4, Chesed (Love, Mercy, Sorrow) on the Sephirothic Tree. Chesed is the first Sephira below the ‘Abyss’ which separates the unformed, immaterial energies of The Supernal Triangle (Sephiroth 1, 2 and 3) from the world of form and matter on the lower part of the Tree.

“The Swift”, Ted said in his BBC introduction to this poem, “has difficulty in bringing himself to a stop in this world of mere matter”, and the swift “does nothing by halves, never delays”. So, no sooner has it arrived over Adam, than it is gone again, casting aside the “two arm two leg article” and all that is associated with the physical body (its own and Adam’s) and hurling itself, “as if” back where it came from, “beyond” the rooftops of the world known to Adam and to us.

The number 4, which is the number of Chesed from which the swift comes, can be written as 2 + 2. In NeoPlatonic Cabbala, this symbolically represents the combination of the abstract energies of Chokmah (the number of which is 2) which lies directly above Chesed on the Pillar of Mercy on the Cabbalistic Tree, and the mirroring of those energies in the world of matter and form. 4, therefore, is said to represent the Principle of Creation (All Father, Chokmah, 2) “manifesting as the four elements out of which all things are created”29. But 4 also represents the cross of matter, the equal-armed cross which symbolizes the conjoined dualities of 2+2.

These conjoined dualities are present throughout Ted’s poem. There is the ordinary, familiar swift (uncapitalized in the title), the migratory bird, Apu Apu, of the species Apodidae (meaning ‘without legs’), which comes to Northern Europe each Spring from the tropical lands where it winters (i.e. from “beyond” the lands where the “lightning-split” oak flourishes). This is the bird which Ted described so beautifully in his earlier poem, ‘Swifts’ (THCP 315). The bird which swims through the air at tremendous speed, screaming as it flies; which hunts minute insects at extraordinary altitudes and skims low over the mirror-surface of lakes to pick up immature insect nymphs. This is the “mole-dark”, “little goblin savage” of Ted’s earlier poem. And it is ‘The Devil’s Bird’ of country folk-lore, the “snarl-gape”, screaming bird, which crawls on stunted legs into the wall-cracks and roof-eaves of the buildings where it nests.

Inseparable from this familiar, earth-bound swift, however, is The Swift (capitalized in the title): the divine messenger which is sacred to the Great Goddess, for which reason its annual reappearance in our world has always been regarded as a sign of luck and renewed fertility. The sacred Swift comes from the realms “beyond” our material world. It flies through the lightning crack in the Creator’s “great oak of light” – which may equally refer to the magical Druidic oak and its connection with the sky and thunder gods and the Celtic goddesses of fire and fertility, and to the Cabbalistic Tree down which the Creator’s lightning flash transmits the energies of the Source. The Swift punctures the “veils of worlds”, flying constantly between spirit and matter, through the veil of illusion which blinds us to anything beyond our material world. Its one wing is “below mineral limit”, existing in the solid, mineral world of the Earth. Its other wing is “above dream and number”, in the realm of vision and abstraction. It is equally at home hunting “the winged mote of death”, the last vestige of our mortality, deep “into” the eye of the sun (the Creator) and picking the “nymph of life / off the mirror of the lake of atoms”. And this ‘lake of atoms’ may be the ever-changing mirror surface of a worldly lake or the creative atomic surface of the sun. In either case The Swift, here, links death and life, just as in the earlier line it “Shears between life and death”, cutting and separating them. Like Alchemical Mercury, Ted’s mercurial Swift makes and unmakes; and it is the agent of death and rebirth.

Appropriately, the fourth letter of the Hebrew alphabet on which Cabbala is based, is Daleth, the Door which is the ‘Door of Illumination’. Four is also the number of the sacred Mysteries, and to understand these Mysteries we must die to the material, egotistical part of our nature and find within us the spiritual Self, so that we may be reborn as a whole, more balanced, individual.

The Swift had perfected this art. It “falls out of the blindness” – which is equally the blinding light of the sun to which it flies and the blindness of the ego-bound self – and it “swims up from the molten”, rising, like the nymph, from the lake of atoms into which all life decomposes at death. So, it joins immaterial to material, “Shadow to shadow”: And it is unlikely to be mere accident that places “Shadow” at the beginning of a line so that it is capitalized and symbolic (like The Swift), unlike the ordinary, material “shadow” to which it is joined.

In its united state, Shadow joined to shadow, the bird “resumes proof” – becomes factual and real – a proof copy of all created swifts. And in these final lines of the poem it seems to rise, like the mythical phoenix from the “papery ashes” of its own “uncontrollable burning” energies. But it nests, too, here on the printed page, born into “papery” physical existence by the burning, abstract energies of Ted’s memory and imagination and the will and determination with which he created the poem. Here is proof that for Adam and his descendents the seemingly magical act of creation is possible. And this is what Ted’s Swift comes to demonstrate to Adam.

‘The Unknown Wren' (THCP 447-8)

“Then a jenny-wren comes to Adam”: “The wren who cannot be made other than he is”30. ‘Jenny-wren’ is a common country and nursery name for the brown wren, male or female, and this bird is also know as ‘Cuddy vran’, (Bran’s sparrow), the prophetic bird of the god-king of early Britain. For the Druids, and for the early British Bards the wren was a sacred bird; a fire-bird associated with thunder and lightning; and the ‘little king’ associated with fertility and the cycles of Nature. Oracles were drawn from its behaviour and its song was used in divination.

Because of the wren’s ancient sacred status it is still considered unlucky to kill the wren or to disturb its nest. But on December 26th, Saint Stephen’s Day, in a ritual which is believed to have been part of the earliest celebrations of the Winter solstice, and which is still practiced in some form in parts of Britain and France, the wren is hunted as ‘King of the Old Year’, caged, and paraded from house to house by ‘Wren Boys’. The traditional wren song which they chant conveys the wren’s status and importance:

The wren, the wren, the king of the birdsWren Day was celebrated in Ancient Greece and Rome; wren brooches have been found in sixth-century, Celtic, burial mounds; and many old, dialect, wren songs, some of which were first collected and published in Tom Thumb’s Pretty Song Book in 1742, are still sung today31.

On Stephen’s day was caught in the furze.

His body is small, but his spirit is great

We pray you good people to give us a treat.

For all these reasons, in addition to Ted’s own description of the birds which visited Adam as “Divine birds”, the wren which comes to Adam is more than just the familiar, tiny, brown bird whose Latin name, Troglodytes troglodytes (‘dweller in caves’), describes its secretive, self-concealing habits. Wrens live in the dark tangles of ivy and in the crevices of dry-stone walls, rather than in caves; and they are rarely seen, although their busy, loud, ringing song and ‘ticking’ warning is constantly heard in the countryside. When they are seen, they are just as Ted describes the singing wren in his poem: “head squatted back”, “upstart tail” cocked, “pin-beak stretched” towards the sky – a tiny, “throbbing” “song-ball” of brown feathers.

The “Unknown Wren / Hidden in Wren”, is clearly the sacred, elemental bird, the Divine messenger, the “guardian exemplary” spirit. Everywhere in the poem, the “unalterable” “World-proof Wren” inhabits the ordinary bird. And again, as in ‘The Swift comes the swift’, the capitalization of ‘Wren’ suggests the Divine status of the Wren within the common wren.

Only in two places is the word ‘wren’ uncapitalized.

In the first, it is used of the “blur of throbbing” of the worldly bird, in which the “nearly out of control” Spirit “Wren sings only Wren” (both capitalized). The ordinary wren is described in human terms, as if the visible, worldly bird is suffering “Electrocution by the god of wrens” – a worldly god, thought up by a human observer.

The second case is more striking. The bird sings as if “in death-rapture”, controlled by the spirit within. In this state, “imminent death” ( which only the ordinary worldly bird can suffer) “only makes the wren more Wren-like”. In death, one would expect that the Wren spirit will be released, but this is not what Ted says in the poem. And to understand why he exemplifies the “Wren-like” spirit in worldly terms of “harder sunlight” and “realer earth-light”, it is necessary to digress and look at the position of this bird on the Cabbalistic Tree and the mythology associated with that position.

Wren is the fifth bird to visit Adam, so comes from Sephira 5, Gevurah (Power, Strength), which lies on the Pillar of Form immediately below Binah, the ‘Mother of Form’.

Gevurah, like Chesed (Sephira 4), lies in the material world below the Abyss, and it reflects the immaterial, unformed but formative energies of Binah. The lightning flash from the Divine Source passes from Chesed to Gevurah and these two Sephiroth work together, but the need to maintain balance between them (as between force and form, anabolism and catabolism) is constant. Chesed creates form in an anabolic, dynamic, unbounded, fluid way. Gevurah preserves form and imposes limits, so that although, as in the Wren, the energies are “almost out of control”, they yet remain within boundaries. Gevurah also catabolizes form: breaking it down so that it does not become fixed and rigid but allows for change and death. Gevurah, it is said, “is the dynamic element in life that drives through and over obstacles”. It is “only destructive to that which is temporal” but “is the servant of [that] which is eternal; for when… all that is impermanent has been eaten away, the eternal and incorporeal realities shine forth”32. Gevurah’s energies, like the Wren’s song, flow out into the world.

The energy of Gevurah, Sephira 5, is the energy of the number 5 which is “the essential number of life”, and is symbolized by the pentagram. In Cabbalistic imagery, the pentagram represents the Human Form Divine and it combines the spiritual and material energies (in our mundane Self and our spiritual Self) which constantly contend for supremacy. Our body is the battlefield, the dark matter, the “wind-buffed wood” (buffed and buffeted by the winds of the world) like that which Ted’s Wren inhabits, and it is in this wood that the “battle-frenzy” must take place. It is here, that the Spirit, the “World-proof” pure energy, the Song is to be found “wresting daybreak” so that illumination (the first dawning of light in the human being) can occur and “a transfiguration” can take place .

Gevurah’s energies battle to preserve the Spirit without destroying the material form. So, Wren, in this sequence of poems which began with song, displays the courage and power of Gevurah by maintaining that spirit song within the bodily form of wren. Only whilst “Wren sings Wren” can formlessness, chaos and death be held at bay. So, the common wren, knotted to the twig of life, is a “song-ball of tongues”. And, so, the more Wren-like he is the more he wields the form-preserving powers of Gevurah and the more real is the “sunlight” and the “earth-light”. And when “Wren sleeps”, everything – “the star-drape heavens” and the “bowl” of Earth – becomes again formless dream and idea, like the potential energy of Chesed which Gevurah must constantly shape.

The ‘Spiritual Experience’ of Gevurah is the ‘Vision of Power’. And the fifth letter of the Hebrew alphabet, He, signifies “life vitality, animation and the breath of sanctity”33. Ted’s Wren, with its power, its energy and its song, demonstrates all of this. It also demonstrates to Adam the will-power and the courage and the constant effort which is required to awaken the Spiritual Self from its sleep within him, and to keep it alive, under control and in precarious balance in the material world.

Gevurah’s ‘Virtue’ is Courage and Energy, but balance is essential. Wise kings (and Wren is King of the Birds) exercise control and do not impose rigid forms of rule and government on themselves or their subjects. Nor do they dedicate themselves wholly to the spiritual or let extremes of spiritual expression take over their kingdom. Only when balance is maintained can the “lifted sun” of Spirit and the “drenched [baptized] woods” of the body “rejoice with trembling”: only then, can the ‘Magical Image’ of Gevurah, which is a crowned warrior-king in his chariot, be seen.

Throughout Ted’s poem, Wren fights for this balance. “But now”, with the promise of light and transformation at the end of the poem, Wren “reigns” and Wren is in control.

Now, truly, Wren is King of the birds and “WREN OF WRENS!”.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

19. Fortune, D. The Mystical Quabala, The society of Inner Light, London, 1998. p.111.

20. Ted Hughes’ mss. note, transcribed and quoted in an e-mail to me by Keith Sagar, 22 Feb. 2009.

21. The Zohar, Rosenkreutzer, Altona, 1785. in Roob, Op.cit. p.276.

22. Fludd’s image, ‘Intigrae Naturae Speculum Artisque imago’, comes from his Utrisque Cosmi Vol.1, and is reproduced in Roob, op.cit . p.501.

23. It is interesting to see these poems in terms of Ted’s lifelong interest in ecology and his view of the essential role we all must play in re-establishing and maintaining the balance of Nature.

24. Graves, R. The White Goddess, Faber, 1977, p.440.

25. Philolethes. Museum hermeticum, Frankfurt, 1678, p.655.

26. Hughes, T. Under the North Star, Faber, 1981.

27. Graves, ibid. pp.98-100.

28. From this egg, Eros emerged to set the Universe in motion. Graves, Greek Myths, Cassell, 1981. p.10.

29. Heline, C. The Sacred Science of Numbers, DeVorss, USA, 1997. p.27.

30. Ted Hughes’ mss. note, transcribed and quoted in an e-mail to me by Keith Sagar, 22 Feb. 2009.

31. My husband remembers singing this song as a boy on the Isle of Man: “We’ll hunt the wren said Robin-a-Bobbin’, We’ll hunt the wren said Richie to Robin, We’ll hunt the wren said Jack O’ the Land. We’ll hunt the wren said everyone./ Oh where, Oh where?, said Robbin-a-Bobbin… / In yonder green bush, said Robbin-a-Bobbin… etc.”.

32. Fortune, D. Op. cit. p. 174-5.

33. Heline, Op.cit . p.43.

Adam and the Scared Nine: A Cabbalistic Drama, text and illustrations © Ann Skea 2010. For permission to quote any part of this document contact Dr Ann Skea at ann@skea.com

Go To Next Chapter