Howls & Whispers: The Averse Sephiroth and the

Spheres of the Qlippoth (2).

‘The Hidden Orestes’, ‘The Laburnum’, ‘The Difference’

© Ann Skea

|

|

‘The Hidden Orestes’

(H&W 3, THCP 1175).

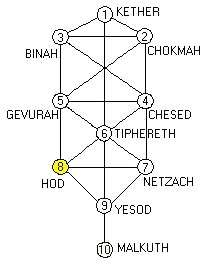

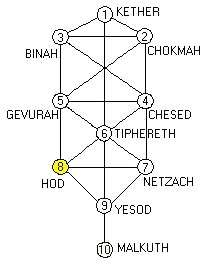

Hod: Sephira 8: Glory. Reverberation.

Element: Air.

Planet: Mercury.

Qlippothic Sphere of Samael.

Virtue: Honesty.

Vice: Dishonesty.

Illusion: Order.

Qlippoth: Rigidity. Rigid Order.

|

Hod is the place where the first awareness of powers beyond

human control come to the one who has become newly

self-conscious through Yesod. At Hod, the mind begins to

look outwards, to question our place in the world, and to

turn to whatever inherited words and wisdom echo our own

predicament and will help us to know and understand it. At

Hod, because there is no direct contact with the Upper

Tree, we turn to the established scholarship of libraries,

museums, history, science and mythology – all

reverberations of ancient wisdom, and echoes which may be

as tricky and deceptive as Mercury, whose energies flow

through Hod.

Mercury is the messenger of the gods, and communication is

an important part of the energies of Hod. So, we encounter

information about the great super-human forces of creation

and destruction which, it often seems, govern our lives. We

look for ways by which to understand these powers; the

patterns in which they function; and the rules by which

they seem to operate. And we discover the ‘Laws’ which have

been laid down by our family, our ancestors, and our

society in order to help us all survive.

The position of Hod, on the ‘passive’ Pillar of Form on the

Sephirothic Tree, means that our relationship to learning

is cerebral and theoretical. And, since Hod is only one

part of the mirrored energies of the Supernal Triangle of

Kether, Chokmah and Binah (the other two being Netzach and

Yesod), its energies alone cannot turn our learning into

understanding. The danger is that we mistake learning for

understanding, and believe that by strictly complying with

the laws passed on to us by the wise, order will be

maintained and we, too, will be wise.

The Illusion of Hod is order, and its Qlippoth is Rigidity.

If the abstract, cerebral world view we acquire through Hod

is false (and we may use our learning, rationality and

powers of communication to rigidly justify and defend it),

then whatever order we appear to have established is an

illusion which must be shattered if we are to progress

towards Truth.

In ‘The Hidden Orestes’, Ted (still, in the poem, at the

unenlightened, developmental level of Hod) interprets his

world according to the patterns of Ancient Greek mythology.

This is entirely consistent with his early acceptance of

the views on religion, poetry, and the poet’s role which

are expressed by Robert Graves in The White

Goddess1.

It was no doubt coloured, too, by his studies of early

religions and shamanism in the Anthropology he read at

Cambridge. And, certainly, there are parallels to be found

between the pattern of events in The Oresteia and

the pattern of some parts of Ted’s life with Sylvia:

enough, perhaps, for him to interpret his own life in terms

of the eternal working out of Divinely ordained ‘Laws’.

The Oresteian Tragedies were written by the poet

Aeschylus some time between 525 - 456 BC. In these plays,

the relationships between the gods and man is explored,

demonstrated and rationally debated. The poet based his

story on the history and legends of his people and on their

religious beliefs. And his characters acted out theological

and ethical dilemmas which were echoed in the emotional,

mental and civic lives of his Athenian audience. In the

end, Aeschylus’s drama supported the established order of

the Athenian State, but the issues he presented are still

fundamental to the way we understand our own world and live

our own lives. And one of the main issues dealt with in the

plays is that of free will.

By interpreting his own and Sylvia’s lives in terms of an

ancient, continuously repeated pattern, Ted suggested that

all the tragic events which befell them were decreed by

‘Fate’. If they, like the family of Orestes, were victims

of a curse which they had inherited, then nothing could

have been done to change anything: Fate decreed the events,

and the order of these events was, so to speak, rigidly

imposed. Yet the Classical Greek pattern which Ted wanted

to impose didn’t quite fit: as the last nine lines of Ted’s

poem admit.

Ted, befogged by love and following the customary patterns

and expectations of his tribe, is certainly like the unwary

“buffoon“ who was, reportedly, married to Electra on her

step-father’s orders. Sylvia, too, is like Electra in that

she wanted to ‘kill’ her mother, because she believed that

her mother was responsible for the death of her beloved

father2.

And Sylvia’s mother, like Clytemnestra, fits the role of a

“banshee”, who heralds the release of deadly maternal

Furies on the husband she regards as “the guilty one”. But,

unlike the pattern of deaths in the Oresteian House of

Atreus, it is the daughter, Sylvia, who dies, not her

mother; and it is the daughter’s husband who becomes the

accused.

Acting the “befogged buffoon”, Ted, “cannot make out“ why

Sylvia is so driven and so jealous of other women. And he

is “alarmed“ by her sudden mood changes – her seemingly

“demonic“ response to some simple, natural thing. But, as

he says (rationally justifying his Hod-like passivity), he

is “not to know“ what is behind all this or what it

portends. This excuse, too, is a defensive response to his

feelings of helplessness. He wants to understand all that

has happened and, because he seems to have been unable to

control events, he tries to interpret everything according

to a time-honoured pattern in which the gods are in charge

of human affairs. But what he “will never get clear“ (or

understand) by interpreting things this way, is why the

gods appear to have got things wrong: why the old

established pattern, which he has learned so well, doesn’t

fit.

The answer lies with the hidden Orestes at the heart of

Ted’s poem. And it lies in the even older stories of

creation, death and rebirth (stories of Heaven and Earth,

gods and man, and shamanic heroes) which exist in every

culture and which seem to be a reflection (or

reverberation) of some fundamental universal pattern.

Beneath the tribal history, story-telling level of

Aeschylus’s drama, The Oresteia is but one more echo

of this universal pattern; and Orestes one more shamanic

hero who undergoes the necessary trials, and returns to his

people with healing energies. Hidden at the heart of The

Oresteia, as at the heart of Ted’s poem, are “the

family emeralds”, which are the real jewels of

wisdom3.

Orestes is the “black panther“ who embodies the Goddess’s

energies. He is the young king, like Dionysus, who kills

and replaces the reigning king. But he also kills his

mother, Clytemnestra, who, throughout The Oresteia

represents the Mother Goddess. And for this crime against

Nature, the Furies pursue him. Apollo, the Mercurial god of

poetry, guides him according to Zeus’s instructions.

Athena’s justice defends him. But the Furies, finally, are

placated only by his rescue of the Mother Goddess (the

image of Artemis) from the deathly land of the Tauris

people; and in this rescue he is aided by his sister

Iphegenia.

So, in The Oresteia, as in Cabbalistic and

Alchemical lore, the loving, creative aspect of the Goddess

is seen to be retrieved from the darkness of our world by

the harmonious union of male and female human energies. So,

she is reunited with the God, wholeness is restored and a

new cycle of Nature can begin. This is a description of the

true ‘Alchemical Marriage’, which restores the human soul

to union with the Divine: and, in the final lines of Ted’s

own version of The Oresteia,4

he carefully and deliberately described it in these terms:

So God and Fate, in a divine marriage, Are made one in

the flesh Of all our people – And the voice of their shout

is single and holy. (O 194)

The “Hidden Oresteia” in Ted’s poem is the Divine Spirit in

us and in our world which, like Dionysus, violently “kills”

or destroys the illusion of order. Such disruptive energies

can cause madness or possession, as they did in the

Maenads. And they do portend death, as a “banshee”

“death-shriek” does, although real, physical death, rather

than symbolic death, comes only to those who cannot, or do

not, learn to find equilibrium in the ensuing turmoil.

At a personal level, in Ted’s poem, there is Sylvia’s death

and the maternal ‘Furies’ (in various disguises) which

pursued Ted and forced him out of his passive state into an

active search for answers. And readers who know something

of Ted’s and Sylvia’s lives may well read events from that

‘story’ into this poem.

However, Ted deliberately couched ‘The Hidden Orestes’ in

impersonal and mythic terms, so that it is relevant to us

all. At any time, the hidden Orestes which is the divine,

Mercurial spark within us, may, like the panther which

kills instinctively and naturally in order that life is

sustained and renewed, set in motion a sequence of events

which destroys the illusion of order in our lives. Those

whose personal identity is closely bound up with the order

they have established for themselves, may panic. Most of us

will find a new equilibrium with which we are moderately

comfortable until the next disruption. And a few will set

out along the long and difficult path towards true

understanding of their place in the world, and for wisdom

which is based on a harmonious balance of learning and

experience, knowledge and intuition, and which requires the

active and continuous discrimination of illusion from the

Truth.

|

|

‘The Laburnum’.

(H&W 4, THCP 1176).

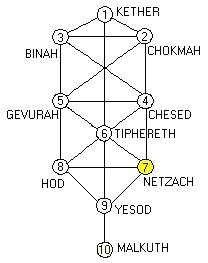

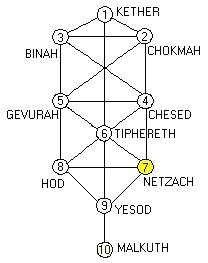

Netzach: Sephira 7: Victory.

Element: Water.

Planet: Venus.

Qlippothic Sphere of Ghoreb Zereq.

Virtue: Unselfishness.

Vice: Selfishness.

Illusion: Projection.

Qlippoth: Habit. Routine.

|

Netzach is the place where we are most influenced by our

emotions, needs, feelings and moods. Like Hod, Netzach

brings us only indirect communication with the Divine

energies of the Upper Tree: but, unlike Hod, this

communication is non-rational. It comes to us through

feelings and intuitions, not through mind-governed learning

or through our five bodily senses.

At Netzach, this intuition of something beyond our purely

physical and mental understanding makes itself felt as a

need beyond the basic needs which are related to our

physical survival. We have a feeling that something is

missing in our lives – something which is necessary to our

security and peace-of-mind but which we can’t quite

identify. We look for it in many places – in our

relationships with others; in our surroundings; in our

occupations and pastimes; and, perhaps, in religion. But in

our unevolved, spiritually unawakened state at Netzach, we

look for it outside ourselves, rather than within us,

believing that other people, material things, and even

images and icons can provide us with all that is necessary

to satisfy this need.

In particular, since Netzach is governed by the Planet

Venus and reverberates with the energies of the Goddess of

Love, we seek to satisfy this unidentified need through

loving relationships with other people. But, since the Vice

of Netzach is Selfishness, such a relationship may be

governed by our own desires, wants and moods, and may be

totally self-centred.

Yet, however self-focussed we may be about satisfying any

of our needs, we are not ready to stand alone. Netzach is

still part of the Lower Tree – still closely connected to

the vegetative Kingdom of Malkuth – and we are still

closely bound to our family, our society, our group. So, we

turn to them for support, see ourselves as we imagine they

see us or want us to be, and respond to the emotions, needs

and desires which they project onto us, or which we imagine

will satisfy their requirements of us. Such projection is

the Illusion of Netzach, and the danger of it is that our

personal identity becomes a mask based wholly on

self-deception, illusory feelings and false judgment.

Netzach, which is at the base of the Pillar of Force,

belongs to the Element of Water. Water can be liquid or

solid. It can change swiftly from a gentle and nurturing

fluid to a powerful and destructive force. Netzach’s

energies are similarly changeable and can be similarly

polarised, swinging from glorious, involuntary vitality to

Qlippothic life-denying rigidity; from love to hate; from

lust to chastity; from ‘Victorious Beauty’ to the hideous

ugliness of the Ghoreb Zereq, the demonic ‘Dispersing

Ravens’ which inhabit Netzach’s Qlippothic Sphere. At the

base of the Pillar of Mercy, Netzach is the seat of

selfless love and compassion, but it can also be a place of

merciless and unflinching severity. And, if the Qlippothic

Illusion of Netzach prevails in us, it can be a place where

we project our own view of the world onto others and

interpret mercy as what we believe is best for their

welfare: being cruel to be kind, we might say.

The Laburnum tree in Ted’s poem, is a symbol of worldly

love. It is a tree which, in myth and legend, is associated

with Venus Aphrodite: and it was an important symbol of the

powerful Love Goddess and of love and security for Sylvia.

She associated it with her beloved father, calling it

“my father’s bean tree” (‘Maenad’ SPCP 133);

and, in ‘The Beekeeper’s Daughter’ (SPCP 118), she

captured the sensuous, sensual beauty of this “Golden

Rain Tree” which, as a bringer of life and death,

exhibits (she wrote admiringly) “a queenship no mother

can contest”. In June 1962, at a time when her

relationship with Ted was seriously troubled, Sylvia still

managed to write ecstatically to her mother of having

six (she emphasized the number) laburnum trees in

her garden in Devon, and they were obviously important to

her. But there is only one tree in Ted’s poem: just as

there is only one Goddess of Love.

Sylvia’s need for reassurance that they would “sit together

this summer / Under the laburnum”, shows how insecure she

felt in the midst of the changes and the emotional turmoil

as their marriage foundered; how much she wanted Ted to

“tell her” their love would survive; and how important and

magical a talisman the laburnum was for her.

Ted’s “Yes” is repeated four times, to represent stability

and to confirm his intent5,

but this was as self-delusory and non-rational a response

as Sylvia’s demand that he say it. And the laburnum’s

deathly, corpse-like aspect in the two lines which follow

this reassurance, indicates the deadly untruth of such an

exchange and the destructive pattern of such self-delusion

and emotional misjudgment.

The following lines, too, indicate the spiritual nature of

the change and sacrifice which must take place if Truth is

to be found and the true Self awakened. The “clock” of the

laburnum is “stuck at noon” – at mid-day, when the sun

reaches its zenith before, as in mythology, dying and

falling into darkness. The laburnum’s “full” sun-yellow

flowers mimic the fullness of the mid-day sun, and they

presage the natural Autumn growth of the tree’s poisonous

seed pods, and (for the tree in Ted’s poem) its own

un-natural death. So, it is both Midsummer – the

traditional time for ritual bonfires and sacrifice – and

“noon”. And the fourfold repetition of “noon” in Ted’s poem

not only carries echoes of ‘bloom’ and ‘doom’ (suggesting

the continuous cycles of birth and death in nature), it

also encompasses the sound, ‘oo’, which in many spiritual

traditions is identified with the Divine Source, and it

embeds that spiritual vibration in

Earth

6.

But “who dug up the laburnum?”. Who interfered with the

natural cycle of death and rebirth? Who usurped the Love

Goddess’s place in Sylvia’s life and ensured that death and

darkness would prevail?

Ted suggests that it was “They”, who were “far off” and

whose words “sawed” and “chipped” at Sylvia’. “They” who,

as if embodying the voracious cravings of the demonic

‘Dispersing Ravens’ of the Qlippothic Sphere of Netzach,

carefully sharpened their “little teeth” and destroyed

Sylvia’s love by telling her “exactly what they thought she

should know”. “They” projected their views of the world

onto Sylvia, and she responded to their emotional

vehemence. Instead of trusting her own instincts, she not

only allowed their anger and revenge, and their plans for

her future, to cut and shape her but she “probably”

encouraged them to do this.

Sylvia correctly identified her need as “the truth”: she

wanted, “Only the truth”. And she was willing to endure

pain to find it. But the demons which exercised their

cravings through the “They” of Ted’s poem, and through the

“hands and “fingers” of her mother, filled her with

“revenge” and a vision of “a future” which she “could not

find in” herself. So, she adopted a mask and projected what

“they wanted” into her world. “They” (still unidentified in

Ted’s poem) “tore up the laburnum”. And “They” showed her

“the raw hole” and the broken “roots ends” which were the

truth of her sacrifice, and which prophetically indicated

the truth of her future, premature death.

“They” were merciless, and their concern for Sylvia’s

welfare was a perverted form of love. But Sylvia’s own

turbulent emotions, her fragile sense of identity, and her

habit of relying on those she loved for support, allowed it

to happen. And Ted, in his own immature, unawakened state

at Netzach, slept soundly whilst “The laburnum

fell”7.

“They” dug up the tree: but in a sense both Ted and Sylvia

were responsible for its death.

As Ted’s poem suggests, the rooting out of false values

based on emotion and on worldly, material things, is

necessary for those who seek the Truth: but it must be done

with the utmost care. And there is a broader meaning to the

poem, too, which is consistent with Ted’s concern for our

treatment of the Goddess and our blindness to the damage

that we do to nature. We must recognize that our true roots

lie in the earth to which we must, ultimately, return. Our

earth-bound roots, like those of the laburnum, are a

fragile, easily broken, life-supporting network, for which

we are all responsible. We should not let others show them

to us “broken in air”, for this truly entails our own

death. We must not rely on what others tell us about

matters which are essential to our own survival.

In Cabbalistic terms, we must somehow learn to use the

energies of both Hod and Netzach without losing touch with

our roots in the earthy sphere of Malkuth. The Wodwo’s

question, “What am I?” reflects our first, primitive

need to understand our place in the world. It is this

question which first leads us towards the light; and, like

Wodwo, we need to understand our connection with “roots/

roots roots roots” 8.

Only this way can be become whole, fully evolved human

beings and discover our true Self.

|

|

‘The Difference’.

(H&W 5, THCP 1177).

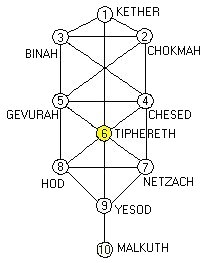

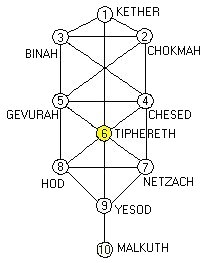

Tiphereth: Sephira 6: Beauty.

Element: Fire.

Planet: Shemesh (The Sun).

Qlippothic Sphere of Tagerion.

Virtue: Devotion to the Great Work.

Vice: Pride, Self-importance.

Illusion: Identification.

Qlippoth: Hollowness.

|

Tiphereth is the most difficult of the Sephiroth to

describe. It lies at the heart of the Sephirothic Tree on

the central Pillar of Equilibrium, and it is at the heart

of a complex of six Sephiroth which represent Adam Kadmon,

the archetype of Primordial, Universal Man, in whom all the

energies are harmoniously balanced. To cover all the

aspects of Tiphereth is, as Colin Low puts it “to cover

most of Kabbalah”9.

In terms of the human journey up the Path of Wisdom,

however, Tiphereth is the Sephira which makes the

difference between our remaining on the lower levels of the

Tree, at a wholly material level of existence in the World

of Assiah, or taking our first step into the upper levels

of the Tree and, for the first time, making direct contact

with the Divine Spark within us.

Tiphereth is a centre of transition and transmutation. It

is the place where inner and outer consciousness touch. And

it is the “Place of Incarnation” of the Divine Child

in us: the “nucleus of manifestation” of our

“higher self”10.

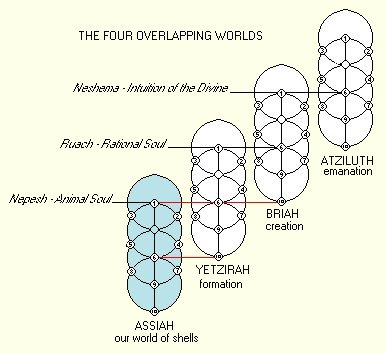

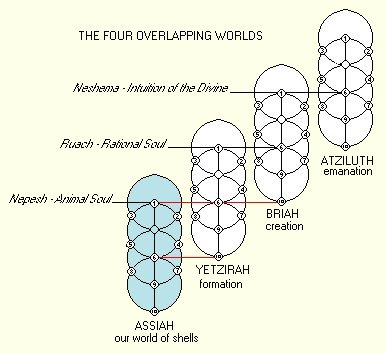

In the overlapping pattern of the Four Cabbalistic Worlds,

the Tiphereth (Sephira 6) of the World of Assiah overlaps

Malkuth (Sephira 10)in the formative World of Yetzirah: so,

we may receive the energies of both these Worlds.

Our first exposure to the higher energies of Yetzirah

represents an awakening of consciousness which, in our

unevolved, immature state on the lower Tree, may be so

sudden and so intense that it is overwhelming. The Sun of

Tiphereth may blind and burn us. Yet, its light should

bring us new and direct insight into our essential nature:

a new, illuminated glimpse of what lies, like a buried

seed, beneath the rational, emotional, sensual persona we

have learned to project to the world as our identity.

Dion Fortune writes that “there is a certain emotional

concentration and exaltation which makes the higher phases

of consciousness available, without which it is impossible

to attain them”; and she likens this to a “burning

fire” in which “all the dross of the nature” is

consumed11.

She writes, too, that “by the very nature of the human

mind, with the brain as its instrument, this white heat

cannot endure for long”, and, whether it brings pain or

ecstasy, it dies away and exhaustion and, perhaps,

emptiness ensue, Nevertheless, the mind has undergone

“an expansion that never wholly

retracts”12.

In the first twelve lines of ‘The Difference’, Ted describe

this process exactly. The emotional and physical collapse

as this uncontrolled and uncontrollable “epileptic”

‘seizure’ takes place, are typical of the sudden stripping

away of the persona which the energies of Tiphereth can

effect. The masks are suddenly gone, like “a dress ripped

off”; the past is “wrenched open”; and what is revealed is

the core of the inner being. It is what we are born with;

the result of what has been; and what, ultimately, is the

source of our deepest needs and strongest drives.

To experience such a moment of Truth is intensely personal.

But Truth is absolute and universal. So, ‘she’ and ‘he’, in

Ted’s poem, might be any couple, although the revelation

each experiences is interpreted in worldly terms according

to their own lives.

We may conjecture that ‘she’, in Ted’s poem, is Sylvia.

And, in the light of Sylvia’s letters and journals, and

other scraps of information we may have about her life, we

may further conjecture that the things which Ted describes

in the first part of the poem took place early in their

marriage. Ted and Sylvia were married on June 16th, 1956.

Some time in June Sylvia received an unexpected letter from

Richard Sassoon, in which he explained his apparent

abandonment of her after a love affair which had lasted

from 1954 until March 1956, when she had expected to meet

him in Paris13.

But “Dickie”, in Ted’s poem, may or may not refer to

Richard Sassoon. And the subject of the parenthetical

phrase “not his name” may, ambiguously, be either “Dickie”,

or the “he” of the poem who is suddenly “out of his depth”

in at least one of the roles he has chosen to play in this

relationship.

Sylvia wrote poetically and ecstatically in her journals

about her love affair with Sassoon. Her “mystic vision

with Sassoon” became part of one of her stories, and

part of a diary entry on 9 March, 1956. And in January 1956

she wrote, “We together make the world love itself and

incandesce”(SPJ 15 Jan. 1956). Yet, even as she

expressed her passion for him, she criticized his lack of

“healthy physical bigness”, and longed “for

someone to blast over him”(SPJ 25 Feb. 1956) and

replace him as her idol. On April 18th 1956, even as she

longed for Ted, she wrote to Sassoon accusing him of

“brutally” deserting her just as her father did when

he died, and she blamed him for the “superfluous

unnecessary and howling void” his long absence had

caused her.

The “choking / Revelation as of knotted lovers / Lifted

from Pompeii’s ashes”, which, in the ambiguity of Ted’s

poem both “she” and “he” see, and which leaves them both

“shaken”, is described in realistic terms and can, if we

wish, be linked with the “knotted” lives of particular

individuals. But the revealed truth of Tiphereth is that

even the closest union of male and female cannot survive if

it is based on masks and self-deception. Nor can any human

relationship, however loving and close, wholly satisfy the

needs of the Divine spark within us.

“He” and “she” in Ted’s poem are both, momentarily stripped

of their masks and illusions, and both are changed by it.

She has “The blame stunned our of her”; he sees an aspect

of her that he has never seen before, and sees his

perceived role in their relationship, “not only as a

doctor”, undermined. And, because of the careful

imprecision of grammatical structure in the sentence which

begins with “shaken” and ends with “survival”, both he and

she survive by the “skin-of-the-teeth”.

This was the first difference that the energies of

Tiphereth made to these lovers’ lives. But it “was nothing”

to the difference which occurs in the final six lines of

the poem and which, although seemingly rooted in historical

events, is expressed in metaphorical and visionary terms.

Sylvia’s awareness of her need for union with a strong male

who would replace her father is frequently expressed in her

journals, as was her need to write. And eventually she

brought these two needs together in her marriage and in her

poetry. So, she combined the worldly, loving, heart-felt

Tipherethic energies of the World of Assiah with the

artistic and formative energies of the World of Yetzirah.

The Sephira at which these two energies overlap on the

Sephirothic Tree, however, is Malkuth in the World of

Yetzirah, which is still governed by Saturn, the Father,

and is still the Qlippothic realm of Lilith and her demons.

Sylvia’s poetic purpose was to get “back, back, back” to

her Daddy; to poetically banish her personal demons and,

thus, to forge a new, whole, identity for herself. But she

allowed the Vice of Tiphereth, which is Pride and

Self-importance, and the worldly energies of Assiah to

direct her Great Work towards material goals. And she

succumbed to the temptations of the demons of Malkuth when

she imagined that she was strong enough to fly

(metaphorically) to the sun on Ariel. Also, believing

herself to be stronger than she was, she poetically

recreated herself as the Bee Queen and declared her

independence14.

By doing so, she challenged the jealous Goddess and, also,

cut herself off from the protective energies of Abba, the

All-Father of the Upper Tree. This was an act of hubris for

which she paid dearly. Her poetic flight brought a glimpse

of Truth, and it was a creative victory, but she was burned

up, exhausted and alone. So, in Ted’s vision in the final

part of his poem, she is carried off, like Persephone, by

the Father God of Earth.

The difference between “her” first exposure to the

transformative energies of Tiphereth and this last one, was

the difference between skin-of-the teeth survival and

death.

The difference between the changes “he” physically

“watched” and experienced on that first occasion, and the

“seeing” which Ted (the mature ‘Watcher’, fully conscious

at Tiphereth) described in the last part of his poem, was a

difference between “nothing” and everything. In a

Tipherethic vision born from his innermost nature and

shaped by all his experiences, Ted glimpsed the Truth and

gained a new understanding of all that had happened.

Given the Cabbalistic framework of Howls &

Whispers, it is not unreasonable to suggest that Ted’s

vision of Sylvia “forever” grasped in the arms of the

“huge-eyed” stranger and trapped in the darkness under “the

floor” of his world was what drove him to attempt the

difficult, healing journey which he undertook for both of

them in Birthday Letters. But it was also his

understanding of the crucial difference between these two

Tipherethic experiences which made him aware of the dangers

of letting his own personal and worldly needs outweigh the

spiritual and universal aspects of The Great Work.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

1. Ted was given a copy of The White Goddess by a

master at Mexborough Grammar School; and, as Faas comments

(UU 71), it “had already turned into a kind of

Bible” for Ted when he was writing his earliest poems.

2. All this is consistent with Sylvia’s own words in her

journals and in her poems.

3. ‘Emeralds’, perhaps, because the wisdom of Hermes /

Mercury (whose energies rule Hod) was found, long ago,

inscribed on an emerald tablet (the Smaragdine

Tablet), which begins: “In truth certainly and

without doubt, what is below is like that which is above,

and what is above is like that which is below, to

accomplish the miracles of one thing”. This belief in

the unity of all, is the hidden light which underpins the

traditional arts of Alchemy and Cabbala.

4. Ted Hughes, Aeschylus: The Oresteia, Faber,

London, 1999.

5. Four is the number of Earth and of the four Elements of

which all things are created. We speak of the four corners

of the Earth; of the four seasons; and four brings

everything together in ‘four-square’, material stability.

6. Cabbalists not only believe in the spiritual power of

particular words (especially those which represent the

Divine Source), they also believe that the sound vibrations

of each letter have specific spiritual energy. It is quite

likely that Ted intended the letter ‘n’, which brackets the

vibrations of ‘oo’, to give each repetition a particular

magical power and, depending on the tone in which the word

‘noon’ is pronounced, that the four-fold repetition may

link Divine and human energies in each of the four Worlds

of the Cabbalistic Tree.

7. In terms of Ted’s own quest for understanding and truth,

the Goddess’s tree was still “strengthening” at this time

of his life. In his own dream world of illusion and folly,

it was “barely” halfway through winter, and the midsummer

noon of burning and sacrifice was yet to come.

8. Here is another fourfold, earth-associated repetition,

this time from quite early in Ted’s work. It suggests that

he was already aware of the magical power attributed to

numbers before 1961, when ‘Wodwo’ was first published

(New Statesman, 62: 347,15 Sept). Ted would have

appreciated the coincidence that ‘Wodwo’ appears on page

183 in both Wodwo (the Faber, paperback edition) and

Ted Hughes Collected Poems. Curiously, too, 183 +

183 = 366, and this reduces to 6 – the number of Venus, the

Goddess who rules Netzach: alternatively, 183 on its own

reduces to 3, the number of the Triple Goddess.

Coincidence? Or another reverberation of the Platonic

harmonies?

9. Low, Notes on Kabbalah, p. 52.

10. Fortune, The Mystical Qabalah, p. 182 - 3.

11. In Alchemy, too, the impure elements of the prima

materia must be burned away in order to reveal the seed of

pure Gold which belongs to the Sephira of Tiphereth.

12. Fortune, op. cit. p. 190.

13. Middlebrook, D. Her Husband, Viking, USA, pp. 45

-6.

14. She does this in her ‘Bee poems’, SPCP 211 -

219.