|

‘The Minotaur 2’(H&W 3, THCP 1175).

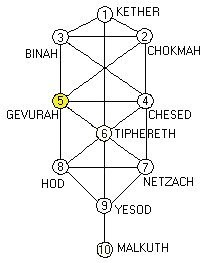

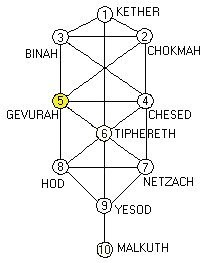

Gevurah: Sephira 5: Strength. Severity.

|

Now, on the Path of Wisdom, Tiphereth is linked to Gevurah and Chesed, making a triangle of energies which mirrors that of Tiphereth, Hod and Netzach on the Lower Tree. If the energies of the Lower Tree have been combined to form the Animal Soul of Nefesh (AKT 137), a new, higher awareness begins to shape our perception and understanding of our world.

This change is clear in ‘The Minotaur 2’, which occupies Gevurah (Sephira 5) on the Sephirothic Tree. Gevurah lies directly above Hod on the Pillar of Judgment and Form and, so, reflects (or mirrors) the Hod-shaped view of the world which Ted expressed in ‘The Hidden Orestes’ (H & W 3). Once again, in ‘The Minotaur 2’, Ted turned to the ancient, inherited wisdom embedded in Classical Greek mythology for support, but he had learned at Tiphereth the difference between knowledge based solely on sense and reason, and the understanding which is possible when that knowledge is combined with intuitive, subconscious and psychic energies.

In ‘The Minotaur 2’, Ted is no longer the “befogged buffoon”, helplessly immersed in a myth, as he was in ‘The Hidden Orestes’. Now, he is detached: he is the Watcher, describing how he ‘saw’ Sylvia and himself as actors in a drama which reflected the pattern of the old myth. He describes how he “saw the plot”; saw the role he played in it and his participation in Sylvia’s “first scene”; and watched her “performance” as the drama unfolded. But he is no longer puzzled by the discrepancies between the Greek story, in which Theseus slew the Minotaur and returned, alive, from the Labyrinth, and the pattern which he saw, in which Sylvia played the heroic role but the Minotaur killed her. Instead, Ted saw the “surreal mystery” which began this drama; and, embedded in the illusory surface pattern of events (just as it is embedded in events in this poem), he saw the gleam of true “gold”.

To understand this, it is necessary to see the Cabbalistic patterns which underlie this poem, and to know the nature of the Averse energies of Gevurah, which is a place of discrimination and judgment governed by the warlike energies of Mars.

The Averse energies of Gevurah are those born of an excess of Gevurah’s Strength and Courage combined with a false interpretation of its Spiritual Vision, which is The Vision of Power. Without the balancing energies of Chesed and Tiphereth, strength and power are expressed in the unbending enforcement of judgment based on ‘Laws’ and rules of behaviour. Strength turns to violence, power become tyrannical, courage is misdirected, and the Illusion of Invincibility prevails.

In ‘The Minotaur 2’, Ted saw how the picnic quarrel (just like the earlier quarrel he described in ‘The Minotaur’ in Birthday Letters (BL 120, THCP 1120) somehow connected Sylvia to an instinctive inner strength which was essential to her poetry and her quest for wholeness. In both poems, that strength is expressed as anger, but only in ‘The Minotaur 2’ did Ted see the true source of that anger and see that although Sylvia also “recognized gold”, she misjudged its origin and meaning.

What that “recognized gold” was, Ted states quite plainly in the sixth line of the ‘The Minotaur 2’. It was “A cry of bereavement”: a cry which, in Cabbala, is the cause of whole Cabbalistic quest. In Cabbala, this is the cry of the Soul separated from the Divine Source; the cry of a Soul bereft and left desolate by this loss. In Hebrew Cabbala, it is the cry of the exiled Shekina. And in Christian and NeoPlatonic Cabbala, is the cry of Fallen Soul, banished from the Paradisal garden and longing to return.

This cry is the gold at the heart of Ted’s poem, but linked with it there (in line 7) is the misjudgment which Sylvia made about it. Sylvia recognized that cry of bereavement from her own experience and her own feelings at the loss of her father. And, as her journals show, she came to see that loss as the cause of all her feelings of emptiness and panic, all her nightmares, all her self-doubt and distress. Her response to this, as her poems and journals also show, was to express her anguish as anger: to try, so-to-speak to kill ‘The Beast’. So, the once beloved human father, who was “the bullman earlier”, became ‘Daddy’ and she killed him with “a stake” in his “fat black heart” (SPCP 222 - 4). Sylvia’s mistake was to look no further than her worldly situation for her sense of loss and, so, she did not discern the spiritual need which was also part of her anguish.

Sylvia recognized that cry of bereavement, recognized that this was what drove her to try and regain wholeness, but she picked up the “skein of blood”, the blood-line which linked her to her earthly father, and with unwavering courage, under the illusion that she was strong enough to be invincible, she followed it, alone, into the darkness and to her death.

Had she been less single-minded and less blinded by anger - had she shown more calm, considered judgment, more love, more patience, more mercy – Sylvia might have accepted help from Ted instead of “ignoring” him. In the Greek Minotaur myth, Theseus, too, had been angry, but he took guidance from the gods and he accepted Ariadne’s loving help and her gift of the magical thread which led him back to the light. Sylvia, too, might have chosen a different thread: not a blood-soaked one which “twitched” like an animal and drew her down into the earth, but a spiritual one which led her up towards the apex of the Tree and to reunion with the Divine Source.

‘The Minotaur 2’ is a poem of judgment, about misjudgment. It is a strong poem, but there is no anger in it. Ted used four-line stanzas for earth-bound stability, and he indicated the earth-bound roots of his own understanding in Classical Greek mythology. But the spiritual energies of Goddess govern the poem with the vibrations of her number, 3: there are three stanzas and twelve lines to the poem; and 12, the governing number of the poem, reduces in Numerology to three.

|

‘Howls and Whispers’(H&W 4, THCP 1178).

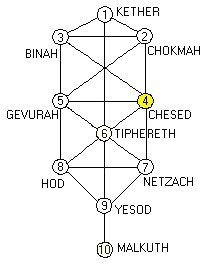

Chesed: Sephira 4: Love. Majesty.

Sorrow.

|

‘Howls and Whispers’ occupies the Sephira of Chesed (4: Love, Majesty, Sorrow) which is linked to Gevurah (5) at the mid-level of the Cabbalistic Tree. Both are linked to Tiphereth (6) and both are Sephira at which we form archetypal visions in our imagination and begin to allow these to direct our goals and actions. At Gevurah our vision of the archetype hero (male or female) inspires and spurs us on, and at Chesed the vision of enthroned Majesty, which embodies perfect love and stability, fills our imagination and becomes our Yetziritic image of ourselves, guides our goals, and is the model of behaviour that we seek to emulate.

At this level of the Tree, the individual spirit (known in Hebrew Cabbala as the Neshamah or Yetziritic Intellectual Soul) links each human being with the Divine Source and is part of the human consciousness, as it was not at the lower levels of the Tree. Now, if the Soul is to grow pure and strong, the individual must learn self-governance; must break down the old patterns of reliance on others; and must accept full responsibility for their own judgments, actions and attitudes. Such a naked, unprotected, unmasked state is not easy to achieve. It requires the strength, courage and determination of the archetype hero of Gevurah, without reliance on rigid, socially established rules. And it requires the powerful love and mercy of the throned Majesty of Chesed, which allows for our own failure and fosters the ability to learn from each failure, but which must remain clear-sighted, unswayed by emotion and unbiased in judgement.

It also requires trust in the innate guiding spirit of the heart – the Tipherethic energies, inner and outer, rational and non-rational, which fill our individual worlds.

Often, as in Alchemy (and especially if the ego-masks which are part of our identity have been long-established and much relied upon) this process of unmasking and honest self-reliance requires a baptism of fire in which the ego must die for the naked spirit to be set free. Those who cannot relinquish their masks, or whose self-governance is not yet sufficiently strong, will remain (perhaps for the rest of their lives) on the Assiahtic plane of Natural Man, in what Blake called “the abyss of the five senses” (MHH ‘A Memorable Fancy’). Metaphorically, this is a kind of death.

In Ted’s poem, ‘Howls and Whispers’, Sylvia undergoes just such a baptism of fire, but for her this so-called ‘initiation of Chesed’ became, quite literally, a life or death situation.

‘Howls and Whispers’, at Chesed, lies immediately above Netzach on the Pillar of Mercy and Force, and it reflects the Netzach poem, ‘The Laburnum’, just as ‘The Minotaur 2’ reflected ‘The Hidden Orestes’ which lay below it on the Pillar of Form. Again, as in ‘The Laburnum’, Sylvia is exposed to the powerful emotional energies of loved ones, mentors, guides and friends. And again, her ability to stand alone and to distinguish truth from illusion is challenged by this exposure. But now, too, her archetypal vision of wholeness – the vision which included perfect mastery of herself and of her writing, and a perfect marriage of equals1 – all this is threatened.

Disastrously, too, the Illusion of Chesed is ‘Being Right’, and this is the illusion which the Demons of Chesed (the Gasheklah: the Smiters and Disturbers of Souls), who are embodied in this poem in Sylvia’s advisors, foster in Sylvia. This same illusion is clearly demonstrate in her advisors’ own words and actions, as is the Qlippoth of Chesed (Ideology), for they base their views on moral codes and “facts”.

Self-righteousness fuelled the joyous “gratification” of Sylvia’s mother, and her advice to “be strong” was the result of her view that Sylvia’s marriage to Ted had always been wrong and that Ted was the guilty party, therefore Sylvia was right to get rid of him.

Sylvia’s analyst offered the ‘right’ advice, based (presumably) on her professional knowledge of marriage breakdown and divorce proceedings: it, too, reflected the assumption that Sylvia was in the right.

And the “professional dopester” who “squatted at” Sylvia’s ear and was the “bug” in Ted’s bed was driven by the need “to prove that only she/ Knew the facts”.

Ted’s description of these people, their interference and the results of that interference is detailed and clear. And it is factual, in so far as he quoted directly from letters which Sylvia left for him to find. Unlike ‘The Laburnum’, however, in which emotion held sway, the disturbers in ‘Howls and Whispers’ use “facts” and rational argument to increase Sylvia’s anger and mental confusion. Ted’s anger and distress in both poems is clear. What is less clear is how, in ‘Howls and Whispers’, as the mature poet and The Watcher at Tiphereth, he used his own Yetziritic archetype visions to place all these events within a Cabbalistic framework in order to obtain a more objective view of them. Such distancing is standard Cabbalistic practice. It provides the Cabbalist with a means of discerning error; of better controlling his or her emotions; and of reframing the past so as to establish a firm base from which to approach the future2.

The clues to Ted’s archetype, mythic vision in ‘Howls and Whispers’ lie not only in the numerology of the poem, where the Mercurial number 8 is strongly present, but also in the Mercurial imagery Ted used. Mercury’s trickster nature is evident in the “bug”, “goblin”, “go-between”; and, since Mercury is the quick-spirited, ethereal messenger, his energies can be seen in all the mechanics of electrical communication and electrical interference (“static”, “bug”, “voltage” “wired”, “tape-recorder”, “step-up transformer”) which are associated with communication in this poem. Most telling of all in revealing the archetype vision Ted held in his imagination as he shaped this poem is his double reference to Iago3, Shakespeare’s superbly believable, human embodiment of all the charming, duplicitous, tricky energies which belong to the mythical message-carrier.

Mercury, the Trickster, dominates Ted’s poem; but to understand why, it is necessary to look at Ted’s discussion of Othello in Shakespeare and The Goddess of Complete Being. “Iago”, Ted writes there, “seems to be the evil one, the emissary of Hell…”. Yet his cool, cynical, calculated actions are not direct emanations of some infernal god’s passion, but “cold” “intellectual reflections” of it (SGCB 228). Iago’s distortions of fact are, like the “garblings” of Sylvia’s advisors in ‘Howls and Whispers’, poured into his victim’s unwary “as-if-sleeping ear”. He, too, preys on his victim’s sexual jealousy, and is an “innocent-eyed” “double spy” who provides “facts” and supports them with dubious proof. His suggestions and proof seem to lead to only one logical, ‘right’ conclusion and yet he works on Othello’s wholly irrational emotions.

Within the overall framework of the “Tragic Equation” which Ted deals with at length in Shakespeare and The Goddess of Complete Being, Desdemona and Othello are seen as personifications of the Great Goddess (as Love Goddess) and her consort. They are equal partners in an Alchemical Marriage based on pure love. Iago, as the personification of the “fanatic but irresponsibly abstract and inhuman intelligence” of the “Puritan Manichean” outlook which governed conventional moral codes in Shakespeare’s time, tests the purity of that love to the limit in a way which was wholly understandable to Shakespeare’s audience.

Sylvia, too, throughout Birthday Letters and Howls & Whispers has been seen as the personification of the Great Goddess, and Ted as her consort – her god /hero/King. Now, in ‘Howls and Whispers’, at this critical point in Sylvia’s growth towards spiritual wholeness, the purity and strength of their love was tested by a whole host of Iagos whose arguments reflected the socially accepted ‘rules’ of morality of their time. So, the dark aspect of the Goddess was released in Sylvia and she experienced the same sort of double vision as that which caused the downfall of Othello and the death of Desdemona. Love and lust became confused: and jealousy, anger and revenge over-rode judgment and mercy.

In Ted’s poem, the furious, destructive, jealous energies which were released in Sylvia were reflected and reinforced (as if by “step-up transformers”) by her Iago-like advisors. She “screamed” all that accumulated “voltage” of jealous, possessive rage at him, but the demons of Chesed, the Disturbers of Souls, had done their work well and her anger did not relieve the torment she was in. So, in the end, those uncontrolled energies killed her.

Beyond the personal story which Ted tells in this poem, and framed within the Tragic Equation archetype by which he shaped that story, is the role which Mercury plays in testing the purity of the Soul. For he is not only the messenger of the underworld gods (including the Hag aspect of the Goddess) he is also messenger of the gods of the highest level of the Cabbalistic tree. He, as psychopomp, can lead the Soul out of the Underworld and towards the Divine Source, and his essential and valuable testing presence is both destructive and generative. He is the Alchemical quintessence which breaks down and dissolves the gross, material aspects of our nature in order to release the pure spiritual gold.

This, then, is the gleam of light which lies buried in the Averse energies of Chesed on the Cabbalistic Tree.

In order to survive the baptism of fire which Mercury administers, however, love must be pure, and the individual strong, vigilant, mature and wise. Sylvia, in many ways was not yet ready for this corrosive test, and death ended any chance that she might learn from this experience and so find other ways continue her quest for wholeness.

Here, at Chesed, Sylvia’s journey ended. But Ted’s did not.

Sylvia’s death, in Ted’s Cabbalistic interpretation of their lives, cast her into the Abyss - the place of unbeing. His lifelong preoccupation with themes of Bardo states, Orphic rescue and other sorts of rebirth from the dead, however, attested to his belief in the possibility of rebirth, and the whole sequence of Howls & Whispers was predicated on that belief. So, Ted’s Cabbalistic purpose in the last four poems remained unchanged as he continued his journey to the apex of the Averse Tree, finding whatever light he could in the qlippothic darkness and gathering it all together so that a new beginning might be possible.

The surface ‘story’ of these final poems, however, differs from that of the earlier poems in that it is no longer the story of their shared lives, but of Ted’s life after Sylvia’s death and of the ways in which he was haunted by her spirit.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

1.The Spiritual Vision of Chesed is the ‘Vision of Love’.

2.“Cabala always connotes motion, both in the way the past is conceived and the way the future is anticipated&hellip… Cabala incarnates this principle of reinventing the past as a structural basis of the future”. Beitchman, P. Alchemy of the Word, State University of New York, Albany, 1998. p.99. This describes very well the underlying re-forming process which Ted undertook in his dealings with the Averse energies in the poems of Howls &Whispers.

3. Sylvia’s mother reiterates advice “like Iago”; and the go-between is an “innocent-eyed, gleeful Iago”.

Howls & Whispers text and illustrations. © Ann Skea 2005. For permission to quote any part of this document contact Dr Ann Skea at ann@skea.com