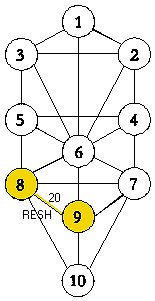

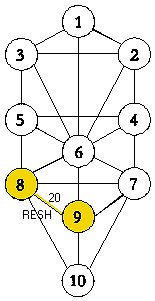

As is common on the Cabbalistic Tree, this lower Path – The Path of the Sun, Tarot Path 19, Cabbalistic Path 20 – reflects those Paths and Sephiroth above it with which it shares numbers. So, the Hermit who on Path 9 carried the light of the Spirit carefully in his lantern now, on Path 19, releases that light into our world (10, The World, completion). And all that was said about Nature and about the energies of Saturn-Cronus on Path 9 also has immediate, worldly meaning on Path 19.

In accordance with the laws of Nature, night gives way to day, darkness to dawn and, as the Sun rises higher, the Moon-shadows vanish and everything is exposed in clear, bright light. Winter, too, passes as the strengthening Sun brings new life to the Earth. All living things are governed by these laws, ourselves included. All life depends on them. And such is their importance and their mystery, that this continuing cycle of death and rebirth is the central metaphor of all those ‘shells’ of the myth, fable, religious lore, ritual and science which we construct in order to explore and explain our world1. These are our mirrors of Truth, and each society explains the mysteries in terms which its members can accept and understand.

In the central myth of Cabbalistic cosmology, Malkuth is the material Kingdom in which all created things contain a buried Divine Spark, and it is the task of the enlightened one (the Tzaddi, in particular) to unearth and redeem these Sparks. So now, on this Path of the Sun, the Cabbalistic journeyer must bring all that has been revealed in the deep unconscious seas of the Moon into the clear light of day.

The energies of Hod (Sephira 8) on this Path are the Soul-guiding energies of Mercury, who now leads the journeyer out of the Lunar Underworld and towards the Spiritual Experience of Hod, which is the ‘Vision of Splendour’. ‘Truthfulness’ is Hod’s Virtue. But ‘Order’ is its Illusion, and ‘Rigidity’ its Qlippoth: so, pride, pedantry, untruth and trickery may mar Hod’s ‘Glory’ and ‘Honour’. The journeyer, here, must be wise to Mercury’s nature and must have a clear understanding of their own if their quest is to succeed.

The very shape of Hod’s number, 8, suggests balance and continuity, as well as the twined serpents of Mercury’s magical caduceus, and the double helix of the genetic material which is the foundation of life on Earth. Its bounding line is endless: turned on its side, the figure represents infinity. And just as the Cabbalistic number for this path, 20, represents two complete, connected cycles of the journey, so 8, figuratively joins an upper, spiritual world with a lower, material world in such a way that both are ever-present and the energies of both come together at a single point.

Everything about Hod on this path associates it with the cyclic patterns of Nature and with new beginnings. On the Sephirothic Tree it lies at the base, the foundation, of the Pillar of Form. It is linked to, and must be balanced by the energies of Netzach (7), which transmits the Life Force of Nature and which is the foundation of the Pillar of Force. On this Path, the energies of both Hod and Netzach are joined with those of Yesod (9) which is the Foundation of all that is made manifest through Malkuth (10). Together, Hod, Netzach and Yod make an active triangle on the lower Paths of the Tree which mirrors the Supernal Triangle of Kether (1), Binah (2) and Chokmah (3) at the Tree’s apex. So, the All Father, All Mother and their Child (Magus, Empress and Fool) are reflected in our material world; and Hod’s Mercurial energies, active in the Sphere of Form, can en-Soul the Life Force of Nature here on Earth. This is the formal magic of Hod, and through its energies the invisible mysteries of Nature (the ‘Moon-child’ of Venus-Aphrodite) are brought into the light and made visible.

For the Tzaddi, the Magus, the Shamanic poet, and for any inspired artist, Hod’s powers on this Path are essential. Not only does the artist stand at the intersection of spiritual and material worlds where Truth may be glimpsed, but Hod enables them to channel that Truth in their work.

The Hebrew letter for this Path, Resh, means ‘Head’ and ‘Beginning’. It, too, is associated with the channelling of Truth into creations here on Earth. It is shaped like a large Yod (which represents the Divine Spirit) and is said to be “pregnant with” the creative force, filled with the “something” in the “created something”. This ’something’ is totally independent of its human creator, it comes in a moment of clarity and wisdom and is accompanied by awe and the “fear of God”. So, Resh resembles the bowed head of the awed human creator or “the mind ‘bending over’ in order to express itself in speech” or in any other Divinely inspired creation2. And this potential for inspired, illuminated creativity is reflected in the Cabbalistic meditation for this Path: “In the Sun is the Secret of Spirit”.

For Hod’s energies to be positive and healing, however, Form and Force, Male and Female, Solar and Lunar energies, all must be united in complete balance and harmony. A second meditation, “The Twins shining forth and playing”, represents this necessary balance and the essentially hermaphrodite nature of Hod3.

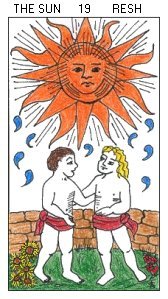

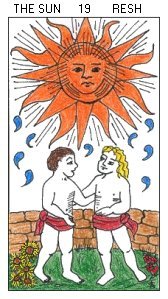

The twins, a male and a female child dancing in harmony in the light of the Sun, are a prominent feature of the Traditional Tarot card for the Path of the Sun. They dance barefoot on the earth, like innocent infant Souls prepared for enlightenment and wisdom. Above them, is the face of our Earthly Sun, the ‘Lord of the Fire of the World’4, with its rays filling half the card. Around them fall nine Yod-shaped drops5, which suggest the energies of the nine Sephiroth which are collected by Yesod (9) and channelled into our world through Malkuth (10). And behind them is a wall, carefully built, so that it suggests that the children are either within their own walled, Paradisal garden (like the laughing children in Eliot’s Four Quartets), and/or that they have stepped outside human boundaries – outside the restraints and rules of conventional social order.

The twins on the Traditional Tarot card are not helpless babes. They are not quite naked, and the way their arms wrap around each other suggests their awareness of each other as well as the loving nature of the ties which bind them. They dance in the clear light of that Sun which, symbolically, brings order to chaos by balancing the Lunar, intuitive, emotional elements of human nature with our rational, ordering abilities and, so, allows for the dawning of Wisdom.

All of this symbolism is apparent in ‘Drawing’ (BL 44- 45) which is the Birthday Letters poem on this Path in the Atziluthic World of Archetypes. The young couple in this poem inhabit a sunlit, timeless scene in which they are happy, relaxed and calm, yet busy. Sylvia “doggedly” captures her vision of Benidorm market on her pad: Ted is “scribbling something” (his choice of the word ‘something’, here on this Path of Resh, can hardly be accidental). Like the twins on the Tarot card, they are outside the ‘walls’ of their usual constraints of work, family, friends and society: they are in a new place – honeymooning in a sort of Paradisal garden – and they feel accepted there and free.

In their shared Cabbalistic journey, too, they are no longer the naive ‘Fools’ they were when they set out: the “tourist novelty”, so-to-speak has worn off and, for the moment, they know their “own ways” about this new environment. Sat on steps “in our rope-souls” (as Ted puts it) the young couple share a simple holiday mode of dress. But also, because of Ted’s frequent use of the paronomasia between ‘sole’ and ‘soul’, they share a new, rough connection with the natural world (rope being a natural fibre, and ‘rope’ also meaning ‘catch’ and ‘fasten together’) and, so, with their own Souls.

With time to relax and play, Sylvia made a drawing of the market place in Benidorm (where the couple lived for a few weeks shortly after their marriage in 1956). What she captured was “the portrait / Of a market place that still slept / In the Middle Ages”: something which was close to nature, instinct and necessity, a scene which was centuries old and which would shortly disappear under the transitory, artificial, dazzle and noise of “a million summer migrants”. With determination, Sylvia captured it, “arresting details” and fixing them permanently on her page6; and Ted, too, as he wrote ‘Drawing’, arrested a moment in time and fixed it on his page. Both worked in “contemplative calm”, ”concentrated quiet”, and “stillness”. Both, like T.S Eliot, tried to convey, in “the form and pattern” of their work, their own experience of that moment of calm which, like the “still point of the turning world”, is where the “dance” of all the energies “is”7.

The form and pattern of Sylvia’s drawings, as Ted wrote in 1965, was “inexorably ordered and powerful” and there was a unity about them in which “nothing” could be “alien or dead or arbitrary”(WP 161). She worked with the sort of care in which “not a line is drawn without intention, & that most discriminate & particular”8. And both she and Ted would have agreed with William Blake’s pronouncement that: “As Poetry admits not a Letter that is Insignificant, so Painting admits not a Grain of Sand or a Blade of Grass Insignificant – much less an Insignificant Blur or Mark”9. Certainly Ted’s reference to Sylvia’s “poker infernal pen”, in the opening line of his poem, was not (in Blake’s terms) ‘Insignificant’. Her “poker infernal pen” (which sounds like a very odd implement) worked “like a branding iron”: very much as did the “corrosives” which Blake used for “printing in the infernal method” – acids which burned and cauterized, “melting apparent surfaces away, and displaying the infinite which was hid”10.

Ted understood Blake’s use of the word ‘infernal’11, with its meaning of ‘place below the Sun’ and its reference to cleansing and purifying Hell-fires. And he recognized that what Blake was doing with his “infernal method” was something which magicians call ‘Drawing down the Sun’. Blake wanted to brand his own visions of eternity and Truth onto his pages as clearly, cleanly and exactly as he could possibly manage. So, he used his pen, his burin and his acids, as a magician would use his wand, or Mercury would use his caduceus, to channel the Divine energies into this world and to give them form. This is what Ted, too, was doing in ‘Drawing’, and what he describes Sylvia as doing in Benidorm. Each was using all their powers, and the ‘Powers’ of poetry and art, to draw down the Sun: to capture a timeless moment so that it might afford others a glimpse of the Infinite.

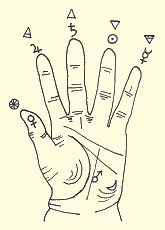

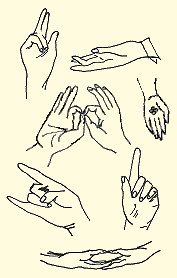

For all Cabbalists, all magicians, and in almost every religion, hands and fingers are the means by which Divine energies are channelled into our world. Michelangelo’s image of God touching fingers with the newly created Adam, is a well-known example of this belief12. The ‘laying on of hands’ is as much part of formal religion as it is of folk-healing practices. And the use of ritual hand and finger gestures in religions, and by those who wish to attract Divine energies or who believe that they can transmit such energies to others, is widely practiced. With the hands, too, or with special tools held in the hands, the artist can create ’something’ which is pregnant with those energies.

For Ted, the picture which Sylvia created in Benidorm retained enough of those energies for him to “drink” from them as he wrote his poem13. Looking at that picture in another time, another place, and not yet in the “endless darkness” in which Sylvia was held, he found that it conjured in his memory the place, the people, and the feelings of that time. And memory, like imagination, is an essential part of the human Soul.

Aristotle described imagination as that part of the Soul which creates “portraits” from memories of past experiences and holds them in memory for contemplation14. This is exactly what Ted did in ‘Drawing’: creating and “Holding this memory” of Sylvia so vividly in his imagination that he shared again the “contemplative calm” which she had “released” in him as she drew. The phrase “contemplative calm” is repeated in the poem in such a way that it links past and present. And, just as Ted “drank” this mood from Sylvia’s “concentrated quiet” then, “now” he “drinks” from her eternal stillness to create this poem.

So, using memory and imagination Ted again entered the “dark adit” between our world and the Underworld of unconsciousness. This time, there was no confrontation, as there was in ‘A Picture of Otto’. Instead, Ted used the form and pattern of this poem to link his hand with Sylvia’s (not just metaphorically in the similarity of their creative endeavours, but also in the words of lines 27 - 30) and to bring her spirit back into the light. In so doing, not only are past and present linked so that Sylvia and he become part of the natural, eternal cycles of change, but Female is linked with Male, Lunar energies with Solar energies, instinct, intuition and emotion with rationality and will, and everything is balanced and in harmony ready for a new beginning. And, by the use of “Now”, in the written and printed words of this poem, Ted joined his own immediate present to that of future readers, so that the pattern became continuous.

In the final two lines of ‘Drawing’, Ted acknowledged and confirmed the continuing and continuous presence of that “stillness” in which Sylvia lies. It is the stillness of death, but also the stillness from which both of them had drawn energy to create that ‘something’ which is the pregnant stillness of Resh: that something which connects us all to the eternal, the seminal, the infinite and ever-present energies which no human can “disturb or escape”, and which are represented in the continuous double circles of the number 8 – the number of Mercury and Hod.

‘Portraits’ (BL 104 - 105) is the poem on this Sun-Resh Path in the World of Briah. Briah is the World of intangible creation, where, ‘something is made out of nothing’ but that ’something’ is a pattern, an abstract concept, a world-view, a potential form. And Resh, too, is pregnant with creative ’something’, some vision of Truth, which the Sun may illuminate and which, through the energies of Hod and Yesod may be drawn down into poetry, art and music. All of this creative Alchemy is present in ‘Portraits’. It is a poem full of actual artistic creation – Howard’s, Sylvia’s and Ted’s. But it is pregnant, too, with some energy which defies definition but is seen as a dark shadow, a Blakean ‘smudge’ which emerges from the dark of Howard Rogovin’s painting and fills Ted with “horrible premonition”.

Just as Ted used Sylvia’s drawing of Benidorm on that day in 1956 to symbolize one new beginning, one new dawning of light in their shared poetic quest, so in ‘Portraits’ he used a painting by American artist Howard Rogovin15 to mark the start of another.

Sylvia and Ted met Howard Rogovin at the artists’ colony of Yaddo in Autumn 1959, and it was here (apparently) that Howard painted Sylvia’s “portrait”. Ted’s own poetic portrait of Howard is that of an artist inspired by “spirits”, an Alchemist at his “crucible”, alight with and lit by the work he is doing. The “Yaddo fall”, the evocative Autumnal smells and rain and echoes of “Tribal conflict”, melt into the rainbow colours of Howard’s fiery “oils”, and Sylvia’s image emerges like a “new-fired idol” from his cauldron. His “tripod” could be his easel, but it could also be the ritual vessel of the Alchemist or magician, the three-legged stool of a seer, or the three ‘legs’ of the Sun (rising, zenith and setting)16. Alchemical Sulphur broods in the Autumn mood, the shadows and in the dark suggestion of “evil”. But Mercurial magic, too, is there in abundance in Howard’s creation, in Ted’s portraits of both Howard and Sylvia at work, in his evocation of the “vital”, “beautiful”, “tentative” snake, and in Sylvia’s own poem ‘Medallion’ (SPCP 124 - 125), where Ted sees the bronze snake’s “dead immortal” shadow-double enshrined.

It is the Mercurial snake which brings all the energies of this poem together. Linked in Ted’s lines to the dark threat behind Sylvia’s image, it swims into Ted’s poem and the flicker of its united-yet-divided “bronze prong” suggests its double nature. It embodies life and death, beauty and horror, Truth (“Snakes are snakes”) and illusion (“It’s evil”). It is magnetic, “hypnotic”, thrilling, inspiring and entrancing. But its Sulphurous poisons, its sinuous life and its deadly magnetic attraction are blocked, suddenly, by the word “Beautiful”, and so it becomes first a creature of evil, then the inspiration for Sylvia’s poem, and finally, the enshrined idol of its dead double.

This pattern mirrors Sylvia’s creative struggle whilst she was at Yaddo, the pains which drove her, the nightmares which haunted her, and the inspiration she drew from Nature’s beauty and was suddenly able to express directly in her poems, working as if “entranced”, and using her thumb and fingers to untangle “a music” that only she could hear. She gave this music form in ‘Medallion’, a poem which she thought of as “a good poem” (SPJ 25 Sept. 1959), one which she was “sure of” (SPJ 29 Dec. 1959). And, towards the end of their stay at Yaddo, and in spite of the dreams and the “Menacing gods” which still haunted her (SPJ 13 Oct. 1959), this new music flowed into a sequence of seven poems which she called ‘Poem for a Birthday’ (SPCP 131 - 137).

Sylvia described these seven poems as “a fine new thing” (SPJ 23 Oct. 1959), very different to anything she had done before, but she was puzzled by them. She found them “moving, interesting” but could not decide “how deep” they were (SPJ 1 Nov. 1959). She certainly did not recognize that they foreshadowed the emergence of her own dark shadow-Self, her dopplegänger, Ariel, even though she structured them as a poetic rebirth. Nor did she hear in her new, direct voice what Ted later described as “the voice of Ariel… clearing its throat”17. But these Yaddo poems, and ‘Poem for a Birthday’, in particular, did mark an important new beginning for Sylvia. She had moved away from the tyranny of the Thesaurus and the Dictionary. And, in ‘The Stones’, she spoke in direct, simple language of a “quarry of silences” in which, with “Love”, she shaped with her “Ten fingers” a poetic vessel for “the elusive rose” which was her new Soul of “shadows”. So, Howard’s portrait had, indeed, revealed a glimpse of Truth: and, as Ted’s intuition told him, it was sinisterly prophetic.

’the Bee God’ (BL 150 - 152), which is the poem on this Path in the World of Yetzirah where the abstract patterns created in Briah crystallize out, is crucial in Ted’s explanation of this sinister shadow. With the additional creative energies of Resh and Hod which exist on this particular Path, the creation of Form is trebly confirmed and the shadow which was prefigured in Howard’s painting now takes Mercurial shape in the light of the Sun. Thus exposed, like everything else on this Path including the Cabbalist, it will be tested to the limit and every weakness, imbalance and lack of wisdom and maturity will be revealed.

Bees are instinctive creators of order and form; and they are Mercurial creatures, full of mercurial energy in their flight and their dancing, and double in their nature, having both stings and honey. They carry the messages of the gods; and at Delphi, oracular Bee-priestesses served both Apollo and the Earth Goddess. Bees are one of the most ancient symbols of the Goddess, and the noise of their swarming is the sound of her Creation. So, they represent her in many of her forms, but especially as Mother Goddess, Astarte, Cybele, Demeter, Aphrodite and Hecate – the Queen Bee whose dark Moon is the Moon of Generation. The bee-swarm, however, also carries the Sky-God, Jupiter’s thunder, and the honey which his bees make (food of Hermes-Mercury, Dionysus and (notably) Shakespear’s Ariel) was the downfall of Saturn-Cronus: intoxicated by the sweet, sensual pleasure of it, he was overthrown by Jupiter and castrated. Neo-Platonists and Hermeticists, too, associated honey with sensual and sexual pleasure, believing that its sweetness draws the Soul down into our fallen World of Generation and keeps it here18.

In the Orphic Mysteries and in the myths which deal with Nature’s regenerative cycles, bees and honey played an important role, and Father-Husband-Son, Mother-Wife-Daughter, each was closely associated with them. At Midsummer, the clash of the Great Earth Mother’s cymbals causes the bees to swarm for her nuptial flight, and after the Queen Bee’s mating her Sun-King is emasculated, killed and deposed to ensure the renewal of fertility in her Earthly hive. Cronus-Saturn, drunk on the honey brought to him by Jupiter’s bees, was emasculated for just this regenerative purpose. And in English country lore, whilst “a swarm of bees in May” is said to “bring a load of hay” and thus foretells a good harvest, May was also the time of May-Eve witch rituals which required the emasculation or death of the Sacred King (WG 404 - 405).

As is usual in Birthday Letters, ‘The Bee God’ describes actual events in Ted’s and Sylvia’s lives, but the mythological, astrological and Cabbalistic associations of the images he chose give the poem an additional, deeper meaning.

In June 1962, Ted and Sylvia became beekeepers. In ‘The Bee God’, it is “summer” and “Maytime”, the Goddess’s time in England19, and Sylvia’s detailed word-picture of her first attendance at a beekeeper’s meeting was written on the 7th June (‘CHARLIE POLLARD & The Beekeepers’ [sic.], SPJ 7 June 1962). The following day she described a visit to Charlie Pollard’s home and the collection of an old wooden hive which she would clean and paint ready for her bees. And on 15 June, close to the summer solstice, she excitedly wrote to tell her mother that she and Ted had “become beekeepers” [sic.], (SPLH 15 June 1962). In that letter, Sylvia described the beekeepers’ meeting, the transfer of bees to her own hive, and how it happened that Ted “flew off with half-a-dozen stings”. All of these descriptions became part of the five bee poems which Sylvia completed between the 3rd and the 9th of October that year. In these poems, she wove her bee-keeping experiences into her own mythos and as she did so she created a new and dangerous chapter in her own ‘religion’.

Early in 1959, Sylvia had written ‘The Beekeeper’s Daughter’ (SPCP 118) where, in a poem full of the luxuriousness of nature, she moved from being a stone under the foot of the “maestro of the bees” to being the queen bee of the wintering “Father, bridegroom”. Sylvia may have engineered this ‘marriage’ within her poem, but the Father throughout the poem is in charge. In her five bee poems of October 1962, however (SPCP 211 - 219), Sylvia begins as “the magician’s girl” but becomes “sweet God”, a woman “in control” of her own destiny. ‘Stings’, in particular, is a statement of independence, where she determines to recover her “self” and is reborn as a “terrible” and terrifying lion queen20, whose workers have made a “third person” a “great scapegoat” (Ted, in reality was the one who was stung), so that “now he is gone”. And in her final bee poem, ‘Wintering’, she and her bees, “all women”, are “flying” into a new Spring.

The ‘voice’ in Sylvia’s bee sequence is her Ariel voice: strong, clear, independent and determined. She is united with her shadow Self and, in these poems, she holds the power and a certain balance and harmony prevail (which is, perhaps, why she chose to end her Ariel book with them (WP 167)). Her tone is matter-of-fact and there is a gentleness in her acknowledgment of the un-named scapegoat and of the “sweat of his effort” which had been the fertilizing “rain” of their world. “He was sweet”, but now she had her own “honey-machine”. She recognized that she was in a new place, in her life and in her poetry, and that it was a scary place of “decay” and “possession”: but she was careful to balance the black “mass”, the blackness of “Mind”, with the long “smile” of white snow in ‘Wintering’. And, from the cold, the stillness, the pregnant “bulb” (a word which suggests stored natural energies as well as contained light), she magically evoked the regeneration of Spring.

So, from the cyclical, natural pattern of fertility in a beehive, Sylvia created a metaphor for the emergence of her own Bee Queen persona. But there were actual events, too, which were built into her poem and, sadly, the balance she achieved in ‘Wintering’ was a moment of calm which did not last.

In ‘The Bee God’, Ted was writing in the context of this Path and with the benefit of hindsight, and he saw things rather differently. He saw that the Mercurial, magical energies of Hod had connected Sylvia directly to the Otherworld. Figuratively, she had stood for a moment at the still point where the two circles of the Mercurial figure 8 touch – the place where all the energies of the two worlds meet. He saw that in the actual, worldly rituals of bee-keeping she was working with the Yesodic energies of Nature; and in the imaginative world of her bee poems she had opened the dark tunnel, the “well” to the unconscious, and that by giving it form in the poem she had ‘married’ Earthly and Spiritual energies together in such a way that Otherworld energies could “come up” out of that well. In a letter to two German translators21 of this poem, Ted noted Sylvia’s linking of these worlds of Form and Spirit when he described her page as a “seething mass and deep compound ball of living ideas—carrying, somewhere in the heart of it… the ‘vital nu-clei’ [sic.] of her poetic operation—her self and her Daddy—and finally, her poem”.

Bowed over her bees in their hive and over the “dark swarm” of bees and words on her page, Sylvia (like the curved, pregnant shape of Resh) created ‘something’: honey from the hive; and the eloquent, intoxication, purifying honey of the words which blossomed on her page, not just in the bee poems but in ‘Daddy’, too. And in Ted’s poem, the double nature of the mercurial bees and their honey is apparent. Sylvia, bowing her “slender neck”, is also bowing to whatever sacrifices this new situation would require of her: bowing to the “weighing” at the heart of it all – the judgement which, in her own mythos of sacrifice and rebirth, must inevitably take place.

This time, too, in her bee poems and in her life, was “Maytime”, time for the rituals which, in the Orphic Mysteries, would ensure rebirth and new fertility: time for the King-Father-Lover to be deposed, killed, or driven off and rendered impotent. And, perhaps, all this had to be achieved before her thirtieth birthday on October 27th, when Saturn returned to her birth-chart and, astrologically, she would be ‘reborn’.

This astrological connection with Sylvia’s ‘Saturn Return’ and a rebirth is not fanciful or insignificant. “Daddy”, in Ted’s poem, is far more than just the dark idol Sylvia made of her dead father. He is the old Father God – Jupiter (Thor, Zeus), Sky God, Creator of Form, Wielder of justice and retribution and, as guardian for the Earth’s fertility, he is the Bee God22 who sent his bees to intoxicate Saturn-Cronus with their honey. The “hot shivering chestnuts” of Jupiter’s royal tree hang their “lit blossom” in the orchard23. And his bees – a “thunderhead” of new souls – are mercurial messengers which belong, too, to Sylvia: they tend her lion-like “golden mane”, like words buzzing around her head24. His “orders” are “geometric”, governed by strict laws of proportion and distance and shape. And his “plans” (‘orders’ and ‘plans’ both have structural connotations) are “Prussian”, which as well as referring to Otto Plath’s German origins also suggests rigidity, and the deep Prussian Blue (astrologically Jupiter’s colour) of Jupiter’s thunderous sky.

As Sylvia gazes into Jupiter’s “cave of thunder”, the first of the bees, like an “outrider” from Jupiter’s court, stings Ted and sets him running like a “jackrabbit”, through a “sunlit” hazard of bee-bourn “volts” and lightnings. Ted is the “target”. He runs like the hunted hare in the May-Eve love-chase of the Sacred King (WG 402 - 405), but it is the bees which are “disembowelled” as they sting him: the hunters, not the hunted, who die. His punishment, however, is not over.

Ted sees Sylvia’s chaos of emotions; sees the conflict of “dream-time” and reality in her; sees in her face and in her actions her attempts to rescue him. But Jupiter’s will is implacable and this chain of events, like the cycles of Nature, is now beyond human control.

Neat as this parallel is between the actual incident in which Ted was stung and the Orphic and May-Eve fertility rituals and myths, there is yet another, much more serious level to these poems. For both Sylvia and Ted, imagination was the ‘heart’s home’ and poetry was their way of trying to make their lives make sense. Between May and October 1962, their marriage was in crisis, and the turmoil of emotions which Ted describes seeing in Sylvia in ‘The Bee God’ was very real for both of them.

In early May, David and Assia Wevill had spent a weekend with Sylvia and Ted at Court Green. Shortly after June 15th, when Sylvia had become a beekeeper (the hive was hers), Aurelia Plath arrived to stay. But in July, Sylvia intercepted a phone call from Assia to Ted25 and Aurelia moved out of the house, because, as she wrote later: “the marriage was seriously troubled&hellip… Ted had been seeing someone else and Sylvia’s jealousy was very intense”(SPLH 17 Aug. 1962). Some time before the 4th of August, Sylvia made a ritual bonfire of some of Ted’s letters and papers26. And on 27 August, she wrote to her mother that she planned to get “a legal separation from Ted” (SPLH 27 Aug. 1962). In September, she and Ted spent a few days together in Ireland, but on 9 October she wrote “I am getting a divorce”. She did not do so, but Ted recorded in his editorial notes to Sylvia’s Collected Poems: “She and her husband separated in October”27.

Sylvia, in her bee sequence poems, asserted her independence and power. They are dated 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 9 October. ‘Daddy’ (SPCP 222 - 224); her poetic exorcism of her Daddy / husband is dated 12 October. And ‘The Jailer’ (SPCP 226 - 7), in which in her fever she dreams of “someone” (who, from the veiled allusions is clearly Ted) and imagines him “impotent as distant thunder”, is dated 17 October. In all of these poems, Sylvia made the crisis in her marriage part of her personal mythos of love, sacrifice, death and rebirth: but the words she collected like honey were often “axes”.

It is this punishing power of words which colours the last part of ‘The Bee God’. This poem is part of Ted’s own poetic attempt in Birthday Letters to make sense of everything that happened to them, and it suggests that when exposed to the fierce light of the Sun on this Path, Sylvia’s Cabbalistic preparation, in spite of her newfound powers, was not yet adequate for the task she had set herself. For many reasons, when exposed to the test, the necessary balance between Love and Will which is part of the wisdom needed at this stage of the journey, was found to be disturbed. And the test to which Sylvia was exposed was very much part of Hod’s Mercurial, sexual, snake energies, and of the dark, jealous, Moon energies of Yesod, which are represented on this Path by Lilith.

Tested by sexual jealousy, all the energies of the Cabbalist on this Path swing between extremes: Love and Anger; Mercy and Retribution; Instinct and Reason; Female and Male. For the Cabbalistic journeyer, the result is a personal chaos to which only the truly wise and mature can restore order and harmony. The need to ‘know thyself’, and to have the strength to resist outside pressures, is vital. Sylvia, in this situation, swung between extremes; and although she asserted her independence in her poems, she still allowed the opinions and the words of others to influence her. These words, too, were the stings of the Bee God’s “fanatical helpers” which came to torment Ted, even as he thought he had removed himself to a safe place. And Ted’s poem, ‘Howls and Whispers’ (THCP 1178 - 1179) 28, which deals with that same few months of 1962, repeats some of these words and describes their effect on him and on Sylvia.

The “lone bee” that flew in to attack Ted in ‘The Bee God’ was, almost certainly, Aurelia Plath on her visit to Court Green29. In ‘Howls and Whispers’, Ted makes it clear that he believed that Aurelia had never forgiven him for having “aborted” and “annulled” the plans she had once had for Sylvia’s career and marriage. He quotes from some of Aurelia’s letters to her daughter: “Hit him in the purse”, “go straight for divorce”, “keep him out of your bed”; and he imagines her “joy” that Sylvia was “ridding” herself of him. The “helpers”, on whom Aurelia called when Sylvia announced that she and Ted were separating, also wrote letters full of stinging words, letters which Sylvia “waved” in Ted’s face like “War-banners”30.

‘Howls and Whispers’ is an angry poem, a howl of pain which lacks the control and the mythological distancing of events which Ted achieved in ‘The Bee God’, but in both poems Jupiter’s retributive energies, wielded by worldly agents, are deadly to Sylvia. In ‘Howls and Whispers’, Jupiter’s “Thunderheads”, his electrical “circuits”, “transformers” and “voltage” do their deadly work: and in ‘The Bee God’, he is, finally, the God whose fanatical helpers are “as deaf” to Sylvia’s pleas as are “the fixed stars” in the depths of the Goddess’s well.

Under Jupiter’s sway, Sylvia’s own judgemental and retributive energies outweighed her love and wisdom; and her words, in her poems and in The Bell Jar, became the axes which she described ‘Words’ (SPCP 270). So, in the final lines of ’the Bee God’, Ted makes reference to Sylvia’s ‘Words’ and picks up images from it so that the ‘fixed stars’, that aspect of Jupiter’s celestial geometry which is seen reflected in the Earth Goddess’s dark waters, come to “Govern a life”31. Had Sylvia been able to balance Jupiter’s controlling powers with the Earth-Goddess’s fertile love at that time, the outcome might not have been so determined.

‘Fingers’ (BL 194), on the Sun-Resh Path in the World of Assiah, is about the energies which survive an individual after death. Again, the ‘portrait’ which Ted draws is a product of memory and imagination but, in describing the channelling power of Sylvia’s hands and fingers, Ted also draws down the Mercurial energies into his own poem and uses them to magically bestow Sylvia’s powers on her daughter. His picture is of sunny, childlike playing; of birds’ exotic, sexual display in a “tropical” sun-filled garden; of “lightning” flashes, “infant spirit”, “puckish” games, jokes, gymnastics and mime. Sylvia’s gestures, like the glittering light in her eyes (which so often in Birthday Letters associates her with the Goddess), are unconscious. Her hands and fingers perform a “routine of their own”, think “their own thoughts”, behave as if “possessed”.

All of this imagery is appropriate to this Path. And the channelling of energies which Ted describes in ‘Fingers’ is something most of us can do. Like children learning to walk, we master certain mechanical skills which become so automatic that it is as if parts of our body (hand and fingers especially) were merely “conductors” through which energy flows without any conscious, rational control. We play the piano, drive cars, type, and our mechanical “expertise”, like Sylvia’s, is expressed in “deft practical touches” made with automatic ease and accuracy.

Sylvia had learned to play the piano as a child and had found that playing calmed her (SPJ 1 Aug. 1951, entry 102). She recognized, too, the combination of automatic skill, instinct and pleasure which it gave her, when she wished for a life that included “banging and banging an affirmation of life out on pianos and ski slopes and in bed in bed in bed” (SPJ 6 March 1956).

‘Fingers’ evokes these Mercurial, life-affirming energies and it describes Sylvia’s calm as, with her will completely suspended, the energies flow through her fingers completely naturally and with a free and generous excess of feeling. It is this automatic “expertise” and the free-flowing energies – not the will-dominated, dogged control of the “poker infernal pen” – which Ted bequeaths, when he carefully (three times) joins Sylvia’s fingers with those of her daughter in the final five lines of the poem32.

Neither Sylvia, nor Frieda are named in these final five lines33. And since Frieda was both Sylvia’s and Ted’s daughter it might seem odd that he should have chosen to call her your rather than our daughter. Yet, by using ‘your’, as he has done so often in Birthday Letters to connect Sylvia with the Goddess, Ted creates a geometry in the final lines by which fingers join the world of the gods with our world. He and Sylvia and Frieda, un-named and represented only by pronouns, become Father, Mother, Child, the worldly triangle of the lower Tree which reflects the Supernal triangle at the Tree’s apex. And “your daughter”, who is now both Sylvia’s daughter and the Goddess’s daughter, takes over Sylvia’s role of priestess – using her own fingers to serve, “obey and honour”. Protected by the Lares and Penates34 in the final, sealing line of the poem, “your daughter” now channels the quintessential, life affirming energies into our world: and, again, the ambiguity of the pronoun in “our house” allows for a double meaning.

The Lares and Penates in the final line of this poem, however, are not just protectors of our house, they are also the fingers – Her’s, yours and your daughter’s – which channel the Divine energies into our world. And fingers are the family inheritance, bequeathed by Nature, through which Resh’s pregnant potential may continue to be expressed. The ability to do this is universal, but skill and expertise must be sought and learned before it can be practiced, and very few, even once expertise is mastered, will learn the qualities which are necessary in order to channel the Divine energies into Duende-inspired art.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

1. Joseph Campbell, in The Masks of God, traced this metaphor in the belief systems of many cultures and over many centuries and he noted the common human need to construct an explanatory cosmology in which the mysteries, “the invisible things of God”, are made visible and are “reconciled” with “contemporary consciousness” (MOG 4, 613).

2. Reish, The Mystical Significance of Hebrew Letters.

3. Crowley, 777, p. 41.

4. This is the Tarot title for this card. Ibid. p.34.

5. The number of these drops varies, but on the Traditional card there are nine, which are coloured blue, like water drops which catch the sunlight and are essential for fertility.

6. Sylvia captured this scene in words, too, in her journal. (SPJ 26 Aug. 1956, ‘Sketches of a Spanish Summer’). Her words and sketches were later published in The Christian Science Monitor Nos. 5 and 6, Nov. 1956 (SPJ Editor’s note 261).

7. Eliot, Four Quartets, ‘Burnt Norton’, lines 137 - 143 and 62 - 67.

8. William Blake’s notes to his vision of ‘The Last Judgement’. Plowman (Ed.) William Blake: Poems and Prophecies, Dent, London, 1970. p.364.

9. Ibid. p. 362.

10. Blake, Op. cit. ‘The Marriage of Heaven and Hell’, p. 49.

11. Ted used Blake’s etchings for The Book of Job as inspiration for the “Alchemical Cave Drama” of Cave Birds and he was very familiar with Blake’s Alchemical and Cabbalistic ideas and methods. I examine this in detail in Ted Hughes: The Poetic Quest.

12. This image can still be seen on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel in the Vatican.

13. Sylvia’s drawing still exists, although the scene which she captured eventually “disappeared / Under” surface changes, and Sylvia, too “went under” into her grave.

14. Ted’s beliefs about memory and imagination incorporated much of the Neo-Platonic teaching which derived from Aristotle. Frances Yates briefly outlined Aristotle’s views on this subject in The Art of Memory, Pimlico, London, 1992. pp. 46 - 47.

15. Howard Rogovin (1927 - ). American artist. Emeritus Professor of Art and Art History, University of Iowa.

16. These three legs are symbolized in Thor’s hammer and in the three-legged swastika, which represents the Sun’s continuous circling and its power in the cycles of Nature.

17. Hughes, ‘Sylvia Plath: The Bell Jar and Ariel’, Thumbscrew 2, Spring 1995, p. 2.

18. Platonists and Neo-Platonists believed that the Soul was drawn down by the intoxicating ecstasy of sensual and sexual pleasures. Thomas Taylor, Platonist and scholar of the Eleusinian and Bacchic Mysteries, described most of these mythological associations in his essay on ‘Porphyry’s Cave of the Nymphs’. Raine & Harper (Eds.), Thomas Taylor the Platonist, Routledge & Kegan Paul, London, 1969, pp. 305 - 308.

19. The May flower, the Hawthorn, blooms throughout May and June.

20. The lion is the hunting form of the ancient Mother Goddess, Innana-Astarte. It is also associated in myth and religion with bees and with regeneration, as in Samson’s Biblical riddle.

21. A copy of Ted’s letter to ‘Andrea and Robert’ (dated 16 June 1998) is amongst the Sagar / Hughes correspondence in the British Library.

22. Sylvia’s father was know as the “bee king”, as if he were the Earthly representative of the Jupiter’s bee-powers.

23. In Magic and Herbal lore the Horse Chestnut is placed under the Dominion of both Jupiter (for provoking abundance and nourishment) and Venus (for provoking lust). In ‘Autumn Nature Notes’, Ted wrote of the “May lamps” of this “royal tree”, (SS 46). Its fruit afforded him a “peek” into the “well-shaft”: and the well-shaft and the stars also occur at the end of ‘The Bee God’.

24. And like new life buzzing around the Biblical Samson’s lion-carcass.

25. In ‘Words, heard by accident, over the phone’ (SPCP 202 - 203), Sylvia described her reaction to this. The poem is dated 11 July 1962.

26. She described this in ‘Burning the Letters’ (SPCP 204).

27. These are the raw facts. No-one but Sylvia and Ted can know what really happened between them at that time, and given the turmoil of emotions which inevitably accompanies such a personal crisis, it is likely that even they did not fully understand all that occurred.

28. This poem deals with events between October 1962 and February 1963. Its title on the publishing proof was ‘Cries and Whispers’ but ‘Cries’ was crossed through and ‘Howls’ substituted. It was first published in the Limited Edition of Howls and Whispers (a title in which a similar substitution was made at proof stage) in 1998.

29. Aurelia’s name carries echoes of the Sky-God’s atmospheric lightnings. And the “blind arrow” of the “lone bee” resembles a Medusa’s nematocyst barb. Sylvia, in her poetic exorcism of her mother, ‘Medusa’ (SPCP 224 - 226), sought to throw off the “eely tentacle” which, in jellyfish, is made sticky and deadly by just such barbs.

30. From Sylvia’s letters and Aurelia’s notes in SPLH between 27 August and 4 Feb. 1963, it is clear that some of these helpers and advisers were Sylvia’s brother and his wife, her Aunt Dot, Olive Higgins Prouty (who had been Sylvia’s mentor since Smith College), and Sylvia’s psychiatrist, Ruth Beuscher.

31. ‘fixed stars / Govern a life’ [sic.] is a phrase which occurs in identical form in Sylvia’s poem ‘Words’ (SPCP 270) and in Ted’s poem ‘A Dream’ (BL 118 - 119) but it does not mean that life is fully determined by the stars. The influence of the stars, ever-present in our world, creates the patterns of energy to which we, as individuals, will react. How we react, however, depends on our own free will and on the strength or weakness of the Spirit within us.

32. Frieda Hughes is, in fact, a practicing artist and poet.

33. The numerology of this poem combines 8 and 5, both Mercurial numbers. Mercury is the fifth Alchemical planet and 5 represents the quintessence: 5 also represents the spirit resurrected from the tomb of matter, and so signifies a new beginning. The poem begins with 17 lines (1 + 7 = 8) and ends with two stanzas of 5 lines – twin stanzas which sit above each other on the page like the two worlds of the figure 8, linked by a light-filled, wordless moment. These two stanzas also suggest the five fingers of two hands.

34. Lares and Penates are amongst the earliest representatives of the gods in our world. Their images used to be placed at the threshold and above the hearth of the family home, where they were regularly acknowledged as mediators between the family and the gods, and as protectors of the gods’ gifts to the family of fire, food, and shelter. They are guardians of the order and continuity of family life.

Poetry and Magic text and illustrations. © Ann Skea 2004. For permission to quote any part of this document contact Dr Ann Skea at ann@skea.com