The Mercurial Spirit which was freed on the Path of Pé, is the Divine Spark – that fragment of Divine energy which lies buried in all living creatures – the Divine Child of the Mother Earth Goddess who is Binah, Mother of All. Some of the oldest names for the Earthly manifestation of Binah are Inanna, Ishtar, Astarte, Demeter and Cybele. Her titles on this Path of Tzaddi are ‘The Daughter of the Firmament’ and ‘The Dweller between Waters’1; and her imminence on Earth is signified by the presence of the ’star’ Venus in our skies.

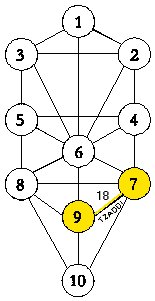

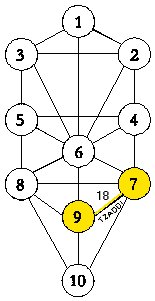

Venus, which is both the Morning Star (Venus) and the Evening Star (Lucifer / Mercury), is the star which lights the Path of Tzaddi – the Path of the Star. And on this Path, the numbers of Venus (7) and Mercury (8) are completed by the addition of 10 (which represents all manifest creation) so that the Cabbalistic number for this Path is 18, and its Tarot number is 17. The Sephiroth which this Path connects are Netzach (7, Victory) and Yesod (9, Foundation). And the governing Element of this Path is Air, the natural element of the Mercurial Child: but the darkness of Saturn, who eats his children, is also present.

The Mother Goddess’s symbols are an eight-pointed star, or rosette; and, also, the crescent moon and cow’s horns, both of which identify her as consort of the Sun God – the Bull of Heaven – and signify their shared role in the Earthly cycles of Nature. The seven-pointed star is hers, too, in her manifestation as Venus / Aphrodite. And the energies of 7, which emanate from the Sephira of Netzach, transmit the life force of Nature, with all its unconscious drives and emotions, to the Path of Tzaddi. The traveller on this Path must learn to balance these powerful energies with those of Yesod (Sephira 9), which acts as an interface between all the upper Paths of the Tree and their final expression in the Kingdom of the World – Malkuth (Sephira 10).

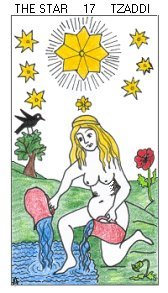

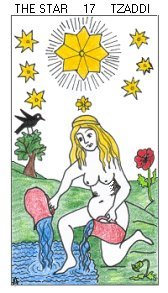

The Astrological ruler of this Path is Aquarius, The Water Carrier. And water is an important symbol on the Traditional Tarot card for this Path of the Star, which shows a young woman, kneeling beside a pool and pouring water from her two pitchers. Nothing in the calm demeanour of this woman suggests her power. But the brilliant eight-pointed star above her head, and the shower of seven-pointed stars (or flowers) falling around her, identify her as Astarte / Venus. She kneels on the earth, demonstrating her presence in our world, but she rests one foot on pool-waters which have been variously identified as the Waters of Life, the Bitter Sea of Binah, and the dark chaotic waters of the unconscious. Here she is, naked and in human form, with all her powers symbolically unveiled.

To encounter the Goddess thus is both awe-inspiring and dangerous. In the Tarot card, the flower which blooms on the hill behind her suggests her generative and life-giving powers. But the black bird, perched atop a tree close by, is a reminder of her other role as Hag, Death Goddess and Queen of the Underworld. So, to bear the full, unveiled force of her energies requires both courage and skill. Those to whom the Goddess chooses to reveal herself – those whose Spirit she will baptize in her waters and fill with her energies – are close to the end of their quest: and the Cabbalistic meditation for this Path – ‘In the Star lies the Gate of the Sanctuary’2 – suggests the proximity of their goal. But the newly born Divine Spirit is as vulnerable as any new soul: it is “walking bare”3, just as Ted described the newborn creature in the Alchemy of Cave Birds (CB 54). And the Goddess, like the ‘Owl Flower’ in that same sequence, is the “Big terror” whose stormy embrace will test them to the limit.

Those who see the Goddess’s naked beauty are enthralled and inspired. They may also be seduced and entranced by her deathly powers. So, they become hooked like a fish on a line, along which the energies flow each way. The Hebrew letter for this Path, Tzaddi (meaning ‘fish-hook’ or ‘to hunt’), holds similar symbolic meaning. Is shape combines ‘Yod’ (hand) of the Divine Source with ‘Nun’ (meaning fish), and it is said to represent the Life Force running upwards towards the Source and returning downwards again to the enlightened quester on this Path – the Tzaddik4 – the fisher.

Such an image would have had special appeal to Ted, for whom fishing was an activity which held a very special place in his life and (frequently metaphorically) in his poems. Fishing, as he told Terry Gifford in a letter in 19945, was a way of sinking himself into “evolution’s mutual predation system”, and he likened it to “Jung’s description of his therapy as a way of putting human beings back into contact with the primitive human animal. Meaning – most neuroses, of individuals and of cultures – result from the loss of contact”. This link with our own deepest predatory instincts allows for that to-fro flow of energy symbolized in the letter Tzaddi. It is part of the imagery of ‘Earth Numb’ (THSP 193-4) and of many of Ted’s other fishing poems. And often, his anglers (hunting for fish, for poems, for the Source or for all of these) wade into dark waters where the fish are spirits, holy creatures which inhabit a primordial world intimately connected to our own.

The Mother Goddess, like the fisherman and the fish in such poems as ‘Earth Numb’ and ‘Pike’ (THSP 41), is both hunter and hunted. The oldest images of her as Innana – Astarte show her carrying her crescent bow and surrounded by star-tipped arrows. In Sumeria, she was know as the lioness, “Labbatu”6, and her animals, always, have been the lion, the tiger, the panther, and all the predatory cats which have her hunting instincts and skills in their blood. On Earth, she has taken many forms: a hare, an owl, a bitch otter, a fox, a trout – all animals which are associated with darkness, the moon and witchcraft – all animals which are hunted, often with customary ritual the meaning of which has long been forgotten.

Hunting is part of her energies and is part of the essential life-blood of all her creatures. Hunter and hunted, eating and being eaten, each is necessary to survival in nature: and we, too, are part of Nature and share that hunting instinct, even though we may choose to use it in different, less bloody ways7. The mystery of death, then, like the mystery of life connects us directly with the Goddess and through her to the Source; and it is the acceptance and use of all her energies which must be learned on this Path where her star shines so brightly.

‘You Hated Spain’ (BL 22) is the poem on this Path in the Atziluthic World, and from the start of the poem Ted deals with Sylvia’s fear of death.

Spain (where Ted and Sylvia spent most of their honeymoon8) was described by the Spanish poet, Lorca, as “a country of death. A country open to death”9. And Lorca’s concept of Duende, with its intimate relationship to death, the creative arts and healing, is an important part of the archetypal framework of Ted’s poem. Duende, as Lorca described it, comes only when “death is possible”. Like the Goddess’s energies it is a “mystery” which “burns in the blood” – a dark, violent mystery which must be fought with “by every man and every artist” in the struggle for perfection. Ted referred to Lorca’s Duende in his own essay on the roots of Baskin’s art. There, he described it as “the core of life”, “the organizing and creative energy itself”, which flourishes “in the bloodstream” and which is “simultaneously holy and anathema” (WP 92). Ted linked it closely with the ancient Mother Earth Goddess as Death Goddess (WP 91), and he, too, believed that this “‘horror’ within the created ‘glory’” is expressed in true art, where it is the source of healing.

The recognition of this violent energy and its power and ‘glory’ were part of the lesson Sylvia needed to learn on her first journey along the Path of the Star: and this was what she did begin to learn in Spain.

Although Ted and Sylvia shared this journey, it seems that Ted had already learned some of the lessons of this Path. He had grown up in a place deeply marked by poverty, war and death. He was familiar with the fascination and the raw violence of hunting and fishing, and had already discovered ways of channelling some of his predatory instincts into his poetry. He felt “at home” in Spain and familiar with its dark, Moorish passions, and he believed that on his father’s side of the family there had even been a Moorish ancestor.

Nothing like this had been part of Sylvia’s experience or her education, and she found the rawness, the poverty, and the constant reminders of violence and death hard to bear. She was clearly fascinated by the different culture and it provided her with some good material for her writing. But she flinched away from the dark passions and the nightmarish undercurrents that she instinctively recognized in Spanish life. Her poems, in particular, became analytical and cold, as if she feared to let any of those energies loose in her imagination. But, significantly, one of the rare moments of fluency in the poems Sylvia wrote at that time10, is her description, in ‘The Goring’ (SPCP 49), of the “art” and the “dance” of bull and picador at the moment when the bull turns and gores the man. This is not exactly the “moment of the kill” which Lorca described when he wrote that Duende was at its “most impressive” in the bullfight, but it was a moment when Duende had irrupted into the bullfight which Sylvia and Ted had watched in Madrid.

The bull’s sudden, instinctive, deadly burst of power and the man’s bloody defeat were, Sylvia told her mother in a letter, “the most satisfying moment” in a ritual which had until then “disgusted and sickened” both her and Ted (SPLH 14 July 1956). In her poem, she tried to convey the horrible beauty of that moment. She caught the sudden, awed “hush” of the crowd and the “faultless”, a-morality and perfection of the horning, and she noted the “redeeming” power of the spilled blood: but she recognized none of the bull’s deadly instinctive powers within herself.

Ted, however, saw in retrospect how that moment, and that poem, opened a path to Sylvia’s own inner nightmares – to those buried horrors within her which she would eventually confront and conquer in her poetry. In ‘You Hated Spain’, Ted vividly conveys the ugly ritual of the bullfight, the blood, the fear and the botched, messy butchering of the “bewildered” bulls. His picture, too, of the goring is ugly, and it is made more so by his image of a horn in a “blowfly belly” – a wound which differs dramatically from the thigh wound which Sylvia described to her mother. Ted’s version, however, suggests the possibility of new life emerging from a deadly wound: rather as the Biblical Samson found bees and honey in the lion’s carcase.

In fact, the belly is a common alchemical symbol for the place of transmutation, and the whole alchemical process of death, putrefaction and rebirth is summed up in Samson’s riddle:

Out of the eater came forth meat,

And out of the strong came forth sweetness (Judges 14: 14)

Nor is the horn in Ted’s poem specifically a bull’s horn. It could also belong to the Goddess whose nightmare land of dreams it opens up for Sylvia in this poem; the Goddess who devours her children and whose Earthy ‘belly’ is the dark tomb-womb of death and life.

Paradoxically, in Ted’s poem this nightmare land of dreams is both in and around Sylvia. He describes it as a land full of horrors which she dared not wake “with” and yet it was also the place she could not wake up “from”. It was her own heart of darkness, a “juju land” which was as much part of her as her “African lips”11. In Spain, although she did not understand its “language” of death, she instinctively recognized that darkness and recoiled. Yet, in the paintings of Bosch (perhaps in his triptychs “Earthly Delights” and “The Haywain” in the Madrid Prado, which deal with the Fall of Man and are full of imaginary, surreal, half-human creatures indulging in all the real and perverted ‘pleasures’ of our fallen world12) Sylvia was touched by the “spidery hand” of the Goddess and she saw how horrors could be transformed into art. And in her own poem, Spider’ (SPCP 48 - 9), she turned to Anansi, the Mercurial spider trickster-god of African and Caribbean folktales, to convey the “barbarous” truth of death and life in our world13.

In ‘Anansi’, too, Sylvia transformed an actual event in which she and Ted had spent half-an-hour “playing god”, as she put it in her journal (SPJ 14 Aug. 1956), into a kind of parable of human arrogance and hypocrisy. She did not spell out this parable, and quite possibly she was not consciously aware of making it, for the “black deus ex machina” in her poem is not two human beings misusing their own predatory powers to disturb the natural balance, but the spider which is hunting ants for food. Her poem, however, does show her awareness of the fact that, to us, the hunt may look like a game, the hunter like a predator satisfying its lust, and the continuing unbroken activity of the group from which the prey is chosen like a lack of “scruple”. All of which moral sentiments we humans frequently apply, inappropriately, to the purely instinctive actions of animals which hunt only to eat. Yet, at the same time, we either refuse to acknowledge our own deliberate killing ‘games’ or, as in the bullfight or in war, we rationalize our actions in some way14.

In her poem, Sylvia did not acknowledge any moral scruple over the deadly game she and Ted had played with the ants and flies; nor did she let any real feelings seep into the poem. She did not spell out any analogy between the creatures’ lives and our own. But she echoed the excuse humans frequently use to avoid responsibility when she suggested that the ants lacked scruple because they were “obeying orders”, although she exonerated them by the phrase “of instinct” which immediately follows, and she made nothing more of this echo.

In Spain, Sylvia clearly became acutely aware of the ugliness beneath the civilized veneer: the “Goya funeral grin”15 which lay beneath the surface of Spanish life. But Ted saw more in her reaction to this than simple recoil: he saw hate, fear and panic. And in retrospect he understood that such excess was Sylvia’s instinctive, self-defensive response to the recognition of some similar, threatening ugliness within herself. Yet this recognition was still unconscious. Sylvia, at this time stood on the edge of her own exploration of her subconscious world, but she was unaware of this. Ted’s final vision of her in ‘You Hated Spain’ suggests many things, but above all it shows Sylvia as the “new soul” she was on this Path. Here, alone at the edge of the Goddess’s waters, lit by the Goddess’s moon, she waits naively for a “ferry” to carry her to safety. She is still happy; still does not understand that her “honeymoon” world has changed. All her poems are “still to be found”: but to find them she must wake, enter these waters, and learn to deal with the horrors of her inner world.

‘Karlsbad Caverns’ (BL 99 - 101), on the Path of the Star in the World of Briah, was another of the poems which Ted returned to the Birthday Letters sequence shortly before it was published. It is one of Ted’s simplest descriptions of a phenomenon of Nature. And it is one of the most straightforward of the Birthday Letters poems in Cabbalistic terms, for it describes, very clearly, the ‘Vision of the Machinery of the Universe’, which is the Spiritual Experience of Yesod (Sephira 9) on this Path.

The bats’ world, unlike that of the humans in this poem, is a “complete” world; a world wholly ruled (with ‘clockwork’ precision) by instinct; a world “connected” to the “machinery” of Nature. Ted’s imagery is mechanical, but the part the bats play in keeping this cosmic machinery running smoothly is clear. They are the necessary oil in its works: that is their purpose, their value and their meaning. Without them, the balance of Nature would change and so, according to the “unfailing logic of the earth” in which everything is precisely linked to everything else, the whole cosmic pattern would be affected: Even such a tiny, fragile, “goblin” as the bat is an essential part of the whole.

Other aspects of Yesod’s energies which are apparent in the imagery of this poem, are the way these bats funnel subterranean energies into our world: they embody Yesod’s function as an interface between us and the mysterious cosmic powers. And, like the bat in ‘9 Willow Street’ (BL 71 74), they are emissaries of the Mother Earth Goddess, they live in her dark caves, and they do her work. The Earth Goddess’s powers of glamour and deception, together with Yesod’s own link with the Moon and the imagination, make this a dangerous Path to negotiate safely. It is a place of transformation and Yesod may function as a Shaman’s tunnel, allowing access to and from the Otherworld, but the Illusion of Yesod is Security; and its Vice is Idleness. All its energies are fluid and tricky and must be carefully balance with those of Netzach (7).

In ‘Grand Canyon’ (BL 96 - 98), the poem which immediately precedes ‘Karlsbad Caverns’ in this Cabbalistic journey, the Mercurial Spirit within the material body was dramatically released. Now, Ted and Sylvia were in new territory in more ways than one. They had certainly not visited the Karlsbad Caverns in New Mexico before, but in a trip where everything was new to them that hardly warranted special mention. What was significant, however, was the new inner world each was “visiting” on this Path, the new Self each was discovering, and the new world-view they each might form because of this.

Ted embeds this thought at the heart of the poem, immediately after the sudden “torrent” of millions of bats has detached itself from the “stone heavens” of their cathedral-like caves and has snaked out and away. The precise timing, the number of bats and the flies they would consume, the huge distance they would travel, and the centuries-old regularity of this phenomenon are awe-inspiring. So, too, for Ted and Sylvia would have been the smoky, snaky, dragonish vision of these goblin representatives of the Goddess irrupting from the earth as if through a “key-hole”. No wonder it stirred thoughts of rebuke about their own “half-participation”, their own meaning and their own indecision.

Here, at Karlsbad, they were at a natural interface between the dark underground of earth and the open light of the sky: and also at a similar interface in their Cabbalistic journey into their inner worlds. The bats were like some huge beast emerging from the darkness, but Ted and Sylvia were indolent, uncommitted, unsure whether to “stay that night or go”. Only when the bats returned amidst thunder and lightning, did they really pay attention to them. “We stared and we saw” : this phrase, with its own internal rhythm stressing the two actions, is set on its own for emphasis. And what Ted and Sylvia saw, “through the bats”, was the terrifying power of Nature: the thunder and lightning, the “mushrooming” clouds, and the Mercurial “genie” of bats detaching themselves “from the love that moves the sun and the other stars” and returning to the dark safety of their cave.

That this sight has both literal and metaphorical meaning in the poem is made clear in the final stanza where Ted conflates the two meanings of ‘see’. There, the open eyes of the bats signify knowledge – they “know how” and they “know when” not to fly in the face of Nature’s power. Unlike Ted and Sylvia, who have yet to learn this lesson, they know how to protect themselves from the love that is the motive force of the universe – the love that underlies everything, as it does in the final line of the poem. Yet, neat as this final summing up of the poem and its lesson may seem, there is, as in Nature, enormous complexity hidden in its seeming simplicity.

“Unlike us” (Ted chose a pronoun which universalised his statement) bats are almost wholly ruled by instinct: they know but they do not understand. This is our common behavioural view of bats and it underpins the human belief that we, who can both know and understand, are in some way superior to them. Part of the lesson on this Path is that we are not. We are different, but, like all the Goddess’s creatures, we are equally subject to her laws. The love which moves the universe moves us too. And Ted, in the final line of this poem, deliberately gives ‘love’ a lower-case ‘l’ so that it denotes the natural, emotion of love, rather than some Divine Source.

Much depends, here, on our definition of love, but it is generally accepted that the emotions of love are strong, irrational and ungovernable, and their motive power is immense. Unlike most animals, we use our mental powers to try and control our response to these emotions and we construct protective frameworks – rules and moral codes – to help us deal with them. So, in human society, we make a distinction between love and lust, and hedge an instinctive drive around with moral terms. This instinctive drive is a fundamental part of the bat’s “complete world” and of their place in the cosmic machinery. Unlike us, they respond to it as directly as they do to the drive to hunt and eat flies, and to the instinct for self-preservation. For us, however, mind may help or hinder our response to all these instincts. With our minds we can evaluate and decide; will action or inaction; and bring endurance and force of Netzach to each situation. But still, we must learn firstly to recognize and ‘know’ the instinctive, a-moral, essential drives within us, then we must learn how and when to use them wisely. Uncontrolled, in us and in our society, they will wreak havoc: equally, if we deny them or misdirect them they will destroy us. Ted believed this to be particularly true for Shamanic poets, for whom the energies of Yesod and its function as an interface with the Otherworld are vital16. But for all of us, the necessary balance of instinct and mind, and of Yesodic and Netzachic energies, requires constant vigilance and care.

In ‘The Rabbit Catcher’ (BL 144 - 146), Ted and Sylvia again meet the energies of Yesod and Netzach, and, now, they are in the World of Yetzirah, where their poems will take shape and form.

Sylvia, at this stage in the journey was especially sensitive to the Yesodic energies. The perfect Mercurial light on the precious Path had announced the birth of her Ariel Spirit. Now, it was essential that she leaned to control this unruly new-born ‘child’.

Ariel’s ‘birth’ took place in April, and was heralded by the Dawn Goddess, Eos. But from the very beginning of ‘The Rabbit Catcher’ the Goddess is present in her most fecund, fertile, fickle and dangerous form. In May, she is both Death-in-Life and May Queen. For centuries, at Beltane on May-Eve, fire ceremonies were held in order to disperse her mischievous spirits of darkness – fairies and furies, witches and goblins – so that people, fields and livestock might prosper. And her fertile powers were invoked in May Day ceremonies, where she and her Greenwood consort (the Green Man or, often, Robin Hood) were feted with music, dancing and general freedom from all customary social restraints.

May, when the deathly perfume of the Goddess’s Hawthorn blossom (known as ‘May’) hangs over the countryside, is traditionally a dangerous month. Her moods, like her weather, change from moment-to-moment according to her whims, and all life is vulnerable. Her green witchcraft and the magical allure of her Spring presence are hard to resist: but her Moon, which controls the winds and tides and the rhythms of fertility and life, can also cause madness and conflict17.

This is the “quirky”, treacherous power in Ted’s poem, where the moon seems so suddenly to have set him and Sylvia to “bleeding each other”. But it is Sylvia, in particular, who responds to it and is possessed by “dybbuk furies”. Ted sees her behaviour as crazy, inexplicable, un-natural. He waits for her “to come back to nature”, but nothing in the nature which surrounds her pleases her. She hates its fences, its farms, its “private kingdoms”. Anything which represents restriction and “private greed” fuels her anger. They drive “West, West”, and Ted repeats the word in the poem like an exclamation, because West is the legendary direction of the Promised Land: but Sylvia makes it plain that Cornwall is not her Promised Land.

And Ted sees this whole scene as a “domestic drama” – his domestic drama – but one in which he is somehow prevented from participating. He sees Sylvia’s fury directed at everything connected with him: his presence offends her; she rejects his country and its ocean; even the children are “hurled” into the car and are fed with a scowl. Her reaction to the rabbit snares is an instantaneous expression of her emotions, and her actions go against every country value Ted holds sacred. Their views of hunting, in particular, are diametrically opposed: and neither, perhaps, takes a balanced view of it.

Yet, although Sylvia rationalizes her destruction of the rabbit snares, so that Ted recognized what she “saw” in them and how it opposed his own view of them, he came to understand that the snares and the trapper were not the true source of her consuming rage. This was a rage which cared “nothing for rabbits”, but Sylvia herself was like a snared rabbit suffocating in its grip: and she lashed out instinctively in self-protection, just as the bull did that day in the bullfight she and Ted saw in Madrid. This, then, was like Duende: dangerous, destructive energy from the Source, suddenly flowing through Sylvia, directed at all restraint and badly needing to be controlled.

In his poem, Ted considers that Sylvia may have intuited some subconscious, threatening darkness in himself. But he suggests, too, that it was her own “doomed”, “tortured”, “self”, the same buried, trapped self which drove her need to write, which had suddenly been released and which she now had to control. “Whichever” it was, Sylvia began to trap those energies in her poems, manipulating them and containing them there. And in the last four lines of his poem, Ted suggests the “terrible”, sensual care with which she did this, feeling the poem alive and feeling its “smoking entrails” come soft into her hands. This is very like the sensual, almost sexual, excitement of the rabbit catcher in Sylvia’s poem of that title (SPCP 193 - 4). And in that poem, too, Sylvia tightens the noose of the snare on her own relationship with Ted.

Ted describes the “hypersensitive fingers” of the final “verse” of Sylvia’s poem, which closed round their relationship. He must also have been aware that by referring to their relationship in the past tense in the ritual framework of her poem, Sylvia had magically killed it there. But, ensnaring and controlling her anger in the lines of her poem, Sylvia created another snare to explain her reasons. So, the very depth and strength of the relationship she shared with Ted became “tight wires”; and their shared thoughts and endeavours became a single “mind” which, like a noose, was closing on some un-named “quick” thing. Sylvia’s use of ‘quick’, rather than ‘living’, suggests the so-called ‘quickening’ of a foetus, and, since the shared endeavour was a poetic rebirth, she seems to suggest that some nascent poetic life was being threatened. Whatever that living thing was, in the final two lines of her “verse”, she linked its plight directly with herself.

Thus, in her poem, Sylvia dissected her relationship with Ted and left the “smoking entrails” there on the page for all to see. But the ambiguity of Ted’s phrase, “felt it alive”, encompasses the life of the poem Sylvia created, and the Poetic Self she was nurturing as she wrote and shaped it, as well as the life in their relationship which, because she felt it as a threatening “constriction”, she instinctively turned-on in self-defence.

The furies of that day in May, the way in which Sylvia used them as subject matter for her poem18, and the way that, finally, she directed them at their relationship, were all things which, at the time, Ted did not understand. But in the context of this particular Path in their Cabbalistic journey, the source of these energies and the lesson Sylvia did learn about channelling them into her poems, are both very clear.

‘Freedom of Speech’ (BL 192) is the last poem on this Path and it is a poem full of ghosts and spirits, as befits its position so close to the Underworld in the World of Assiah.

Sylvia and Ariel both are present (although Sylvia did not live to celebrate her sixtieth birthday); her dead father is a ghostly participant; her mother and her children are there in spirit; so, too, are the spirits of old and new friends and of many others. The “whole reunion” is conjured up in Ted’s imagination; and he sees Sylvia and Ariel lit, not by sunlight, but by the “cake’s glow”.

Birthday cakes (traditionally round in shape) were, originally, cakes eaten at feasts which celebrated the death and rebirth of a god. They had sacrificial and totemic significance, and the candles associated with them were small fire-rituals intended to ward off evil spirits and protect the new-born soul. In folk-lore, too, the candle flame itself is often believed to be a naked soul. In feasts associated with Innana / Astarte in her manifestation as Moon Goddess, round Moon-cakes were offered to her. And, with the ambiguous ‘your’ in the first line of this poem, Ted once again identifies Sylvia with the Goddess.

In this dim, Earthy World of Assiah, the manifestation of the Goddess which Ted chose for his poem was the old Phrygian Mother Earth Goddess, Cybele, the Goddess of Caves. Ariel, whose name means ‘lion’, is Cybele’s creature: lions draw Cybele’s chariot and sit on either side of her throne19. Ariel (notably genderless in Ted’s poem) sits on her “knuckle” (another ambiguous ‘your’, here, encompasses Sylvia and the Goddess) and is fed with grapes from her mouth: “a black one” the colour of her earth, her cave, her night and “a green one”, the colour of her fertile land20. The grapes, too, are a symbol of her husband/son Attis (another form of Dionysus); and the laughter (like the intoxicated laughter caused by fermented grapes) is like the unrestrained joy of Cybele’s priests at the festival which greeted her return, with Attis, from the Underworld21.

The poppies, too, are the Goddess’s flowers. Sylvia called them “little hell flames”, “bloodied skirts”, and “a lovely gift” in her two poppy poems22, where she accurately conveyed their symbolism as flowers of narcosis, enchantment, death and resurrection. In Ted’s poem, they are “late poppies”, Autumn poppies. And, just as the Goddess disrobes as she enters the Underworld and winter’s bareness comes to her earth, one “loses a petal”23.

Sylvia’s was born in the Autumn: her natal birthday was 27 October 1932. But her poetic rebirth and the ‘birth’ of Ariel took place in April 1962, and Sylvia acknowledged this when she chose A Birthday Present as one of her earliest titles for her book of Ariel poems (‘Introduction’ SPCP.5). April, too, was always the month of the return of the Goddess from the Underworld with her son/lover and the renewal of fertility on Earth. So, Sylvia and the Goddess shared this April birthday as a time of birth and rebirth.

It is not just months that are important in Ted’s poem, however. Years are important, too. And to explain this, it is necessary to look closely at the dates of some of Sylvia’s poems and at the way in which her concern with birth and rebirth recurs in them.

Early in 1962, Sylvia began to date and keep all the drafts of her poems (‘Introduction’ SPCP 17), so dates, apparently, had become important to her. The poem ‘A Birthday Present’(SPCP 206 - 8), from which Sylvia took the proposed title for her book, is dated September 1962, several months after her Ariel voice was born. In this poem, as if she were aware that the birth of Ariel was not the end of her quest, Sylvia asks for a revelation. And the imagery she used – choosing words like ‘annunciation’, ‘enormity’, ‘veils’ and ’transparencies’ – is very like the Cabbalistic imagery in which the Goddess, mediator of Divine energies and Guardian of the Gate of the Sanctuary, conceals the Divine Source behind veils of illusion. In this poem, too, Sylvia expresses great impatience: and she does not want to have to wait until she is “sixty” to receive her “gift”. Then, on her thirtieth birthday a few weeks later she wrote two amazing poems about rebirth – ‘Ariel’ (SPCP 239-40) and ‘Poppies in October’ (SPCP 240).

In ‘Ariel’, Sylvia merged her energies with those of “God’s lioness”, to fly like an arrow (which in Cabbala flies directly up the central column of the Tree to the Source) into the rising sun. In ‘Poppies in October’, she celebrated a blooming, a “gift”, a fresh blue dawn which breaks up a “forest of frost”. And in the poems she wrote in the next few weeks, she wrote of the stirring of the veil (‘Purdah’) and a rebirth (‘Lady Lazarus’); and, most importantly, love lit up her poems (‘Nick and the Candlestick’, ‘The Couriers’) before the darkness began to close in on her again.

Sylvia was thirty when she used her poetic magic to merge her energies with those of Ariel and fly to the sun. In Cabbalistic terms, thirty (3 x 10) is the age at which the Mother Goddess (3, the number of Binah) may channel her energies through the Initiate into our world (10, Malkuth). But the power, the balance and, especially, the self-control necessary to direct those energies for whatever purpose the Initiate chooses, is not easily learned or easily applied. Astrologically, too, thirty is an age at which the planet Saturn exerts its influence most powerfully in our lives24. Clearly, with two such powerful deities present in Sylvia’s life at that time, it was appropriate that she should attempt her flight to the Source, but it was an extremely dangerous thing for her to do. Ted’s analysis of Sylvia’s journey along the earlier Paths in Birthday Letters has already suggested that she was not sufficiently prepared. And her choice of Ariel as her steed – Ariel who was either Mercury or Lucifer depending on which aspect of his Mother Goddess he was representing – only increased the danger.

Ariel’s ‘birth’ was a ‘Victory’ for Sylvia, a sign that she was making use of Netzach’s powers, but it was a victory which was overshadowed by the darker side of Yesod. Disastrously, Sylvia was too strongly influenced by the Illusion of Yesod: Her world view was unbalanced, she was too ready to identify with Ariel and too sure that she was right to proceed as she did. All these illusions, too, were exacerbated by the Goddess’s own lunar powers of enchantment and possession: And the Goddess, like Saturn, eats her children.

Had Sylvia been self-controlled and patient enough to wait for her sixtieth birthday, her own maturity would almost certainly have brought more wisdom, experience and balance, and she would have had more control over Ariel. At sixty, astrologically, Saturn’s influence is again strongly present in our lives. And at sixty (6 x 10) the Goddess’s powers (3 + 3) are doubled, but they are directed through Tiphereth (Sephira 6, The Way) at the heart of the Tree and are channelled from Malkuth (10) directly up the Path of the Arrow to the Source. So, all the energies would again have been in place, and Sylvia might have successfully completed her journey.

Sylvia died at the age of thirty but she had brought Ariel into the world and Ariel’s strong, ambivalent energies live on in Sylvia’s poems. In ‘Freedom of Speech’, Ted, like a Tzaddi fishing for fragments of soul – pieces of the broken vessel of a failed Creation – gathers up Ariel and returns this wayward child to Cybele’s cave. Sylvia is there, in the semi-darkness, and many others too: notably, all those who have benefited from or been influenced by Sylvia’s freedom of speech and the lack of restraint in her writing and publishing. Notably, too, her immediate family, although there in spirit, are not present in the cave’s gloom, and Ted himself is not a participant. Everybody but Sylvia and Ted are delighted and full of laughter: the candle-tips (little soul-flames) tremble with joy; the stars, too, (more little spirits – flickering sparks in the Goddess’s dark sky) shake as if racked with laughter. But there is no real merriment about Ted’s poem: and only the movement of the stars and candle-tips suggest the intemperate, all encompassing, nature of that laughter25.

And “what about Ariel?”, Ted asks. What indeed? Ted’s question is thought-provoking. And if Ted really was intent on creating a magical healing ritual in the Cabbalistic poetic journey of Birthday Letters, then the numbers associated with Ariel in this poem are important.

Ariel is named in the poem four times, and so associated with the Platonic number of stability and Earth, and the Sephira Chesed’s energies of Mercy and Love. There are four stanzas to reinforce these associations; with five lines in each to bring the Justice of Gevurah to bear. Ariel, as is the practice in ritual magic, is named three times in the final stanza, the final time stating that “Ariel is happy to be here”: here, Ariel is contained within Ted’s poem; here, Ariel is back in his Mother Goddess’s cave and under her control. And the seriousness of this whole magical, poetic ritual, is underlined by the seriousness of Ted’s final, separate line.

This may be a comforting scenario, but another meaning of ‘here’ is also possible. Ariel is, as has already been noted, still here in our world and still has a powerful influence on readers of Sylvia’s poems. Ariel, no doubt, is happy to be here: and the Mercurial energies Ariel embodies are essential in our world. Ariel’s energies, of course, are also present in the world through Ted’s poem, but the poem is notably sober in mood (in spite of all the laughter it describes), thus providing a balance for the fiery energies released in Sylvia’s poems. Importantly, Ted does not destroy the Ariel spirit in his poem, only confines its energies within a ritual framework, and returns it to the cave-womb of the Mother Goddess ready for rebirth. But the use Sylvia made of Ariel’s voice was quite different.

Freedom of speech is a necessary liberty, but it requires the utmost self-control: without that, it can be costly. Words, especially, carry the gods’ power. They are regarded as supremely powerful in religion, in Cabbala, and in Cabbalistic magic. The Word on the breath of the Source created our material universe; and the word of the Divine child is the worldly expression of that power: as in St John’s teachings in the Bible – “In the beginning was the Word, and the word was with God and the word was God”. Consequently, misuse of words, especially by an Initiate, is forbidden. And Ted repeated the phrase “forbade it” or “forbid it” ten times in ‘Costly Speech’ (BL 170 - 1) to suggest the enormity of Sylvia’s transgression of this ban.

Sylvia well knew that “riderless words” (as she put it in her poem) could be deadly “axes”, and that their power could echo down the years: and it is significant that Ted chose Sylvia’s warning poem, ‘Words’ (‘Words’ SPCP 270), as the final poem of the first published collection of Ariel poems. Yet she went ahead and published words which she knew might hurt others. The example Sylvia set then, and later in her free use of Ariel’s angry voice, demonstrated publicly that unrestrained freedom of speech was allowable, even acceptable. Her Ariel poems were, indeed, a great achievement for her: but they have encouraged others to express themselves with equal, often devastating, freedom. It is understandable, then, that at the end of ‘Freedom of Speech’, despite all the laughter, Ted and Sylvia, alone, do not smile.

(NB. I am grateful to Neil Spenser and Colin Low for discussing aspects of ‘Freedom of Speech’ with me. My interpretation of the poem is entirely my own, but Neil’s astrological advice on moons and Saturn returns, and Colin’s suggestion that the concept of teshuva might be worth investigating, were both invaluable).

REFERENCES AND NOTES

1. Crowley, The Book of Thoth, p. 110.

2. Crowley, 777, ‘Gematria’ p. 25.

3. ‘Walking Bare’ beautifully describes the gem-like purity and the “appointed” status of a newborn soul-spark in its Earthly setting.

4. In the Hebrew Sephir Yetzirah, the enlightened Tzaddik on this Path hunts for fallen sparks, broken vessels, soul-fragments of a failed Divine Creation. When found, these are, metaphorically, ‘eaten’ by the hunter in order to reconnect them with the Divine Source and in this process the soul of the Tzaddik becomes increasingly conscious of Divinity and increasingly able to reveal it and draw its healing energies into our World. Jesus, the Fisher of Men, was just such a Tzaddik; so, too, were other prophets and saints. But mediation between human and divine is also the role of the Shaman and, traditionally, of the poet.

5. Gifford. T, ‘Go Fishing: An Ecocentric or Egocentric Imperative’, Lire Ted Hughes (Ed. Moulin) Editions Du Temps, Paris, 1999.

6. Baring and Cashford, The Myth of the Goddess, p.204.

7. Ted discovered his own hunting instincts very early. He wrote about this in Poetry In The Making (Faber, 1969. pp. 15-17) and wrote, too, of his belief that hunting and the writing of a poem are essentially the same activity.

8. Sylvia’s journal entries began in Spain on 7 July 1956 and show that by 23 August 1956 the couple were back in Paris.

9. Lorca, F.G. ‘Play and the Theory of Duende’, Deep Song, New Directions, N.Y., 1980, pp 42-53.

10. ‘Fiesta Melons’, ‘The Goring’, ‘The Beggars’ and ‘Spider’ (SPCP 46 - 49). Not until July 1958 was Sylvia able to tackle the dark undercurrents of death and birth of which she was aware in Benidorm. In her poems ‘Old Ladies Home’ and ‘The Net Menders’ (SPCP 120 - 121), she uses moony imagery of fluent beauty to deal with things which she described in her journal as “closed to me as a poem subject till now”. (SPJ 12 July 1958).

11. Images which suggest sexual witchcraft and passions associated with Sylvia’s lips as well as their fullness.

12. Hieronymus Bosch (c 1450 - 1516)

13. The note on ‘Spider’ (SPCP 275) identifies the source of Sylvia’s Anansi.

14. Ted discussed the complex subject of morality and killing in detail in an interview with Ekbert Faas in 1971. This interview is reproduced as ‘Poetry and Violence’ in Winter Pollen pp. 251 - 267, and the beliefs Ted expressed there, offer invaluable insight into the way in which he deals in Birthday Letters with the predatory instincts encountered on the Path of Tzaddi.

15. Sylvia and Ted may have seen Goya’s work, too, at the Prado in Madrid. In the words of one art-critic, Goya “assuredly made beauty out of ugliness and horror” (James, P. Arts Council of Great Britain, Goya exhibition catalogue, London, 1954): and in Goya’s depictions of human folly and perversion in Caprices, Proverbs and, especially, in Disasters of War, that grin of horror and pain is plain on many human faces.

16. Speaking to Ekbert Faas in 1970, Ted described the Shamanic call, its ancient association with poetry, and the special difficulties for poets in our present society of accepting or rejecting that call. UU 206.

17. In Ancient Babylon she was “Lady of Battles”. In Enheduanna's Prayer (2285-2350 BCE) she is “Queen who rides the Beasts”, but also “Destroyer of Foreigh lands” and “All devouring in Your power”. Pritchard, J. The Ancient Near East Vol II , Princeton University Press, 1975.

18. Ted commented on Sylvia’s use of their bad moments as the subject for her poems in a letter to Janet Malcolm, quoted in The Silent Woman, p. 143.

19. In Sylvia’s poem ‘Ariel’ (SPCP 239 - 240), she calls Ariel “God’s lioness”, but the God of the Divine Source is pure, genderless energy which is expressed on the Cabbalistic Tree as ‘male’ or ‘female’ potencies not as gender-defined beings. Cybele, like all gods and goddesses of the Paths, is simply one expression of the energy of the whole.

20. Together, these two grapes, “a black one” followed by “a green one”, complete the winter-summer, night-day, death-rebirth wholeness of the Mother Earth Goddess’s cycles of Nature.

21. In Rome, this feast was know as ‘Hilaria’ (Feast of Joy) but it was also called the ‘Day of Blood’, because in a state of ecstasy and possession men would voluntary emasculate themselves and become Galli, Priests of Cybele. Cybele was imported to Rome from Greece in 204 BCE. Rome curbed the wild celebrations associated with her ‘birthday’ and instituted the Megalesia – seven days of freedom from public and legal duties, filled with processions, games and drama. In Rome, the final day of Megalesia (10 April, until the date was moved closer to the vernal equinox) was officially The Great Mother’s birthday.

22. ‘Poppies in July’ (SPCP 203) and ‘Poppies in October’ (SPCP 240). Both poems were written in 1962.

23. The earliest known description of this disrobing of the Star Goddess is found in ancient Sumerian texts, which tell of Ishtar’s descent into the Land of Darkness ruled by her sister, Ereshkigal, in order to bring back her lover, Tammuz, to the World of Light.

24. Neil Spencer writes that Saturn’s return to our birth-charts between the ages of twenty-eight and thirty “marks a point of reckoning, a crucial stage in our personal development. Saturn is the planet of limitation, responsibility and earned success, its return represents a time when boundaries are broken and outworn structures abandoned.”, True As The Stars Above, Gollancz, London, 2000. p. 51.

25. For the Ancient Greeks, Aphrodite was the laughter-loving goddess. But the laughter of the gods is always to be feared; and in folklore laughter is often regarded as a challenge to the gods and is, therefore, unlucky.

Poetry and Magic text and illustrations. © Ann Skea 2004. For permission to quote any part of this document contact Dr Ann Skea at ann@skea.com