Ted Hughes and Small Press Publication

(My thanks to Olwyn Hughes for her help and advice; to Mark Hinchliffe; and to his daughter, Sarah, whose photographs I have adapted for most of the images of Rainbow Press books used here).© Ann Skea.

Addendum, November 2016:

Robin Skelton archive, University of Victoria, B.C. (SC114). In a letter from Ted Hughes to Robyn Skelton, c. Dec. 1962, Hughes writes of his own idea to edit and produce an annual or twice–yearly magazine devoted to translations of modern poetry of other languages. This letter was written a year before Daniel Weissbort’s remembered conversation with Hughes about this subject on New Year’s Eve 1963/4. The first edition of Modern Poetry in Translation, with an editorial written by Hughes, appeared in October 1965.

In his ‘Programme Notes’ for the first Arts Council Poetry International Festival in 1965, Ted Hughes expressed the view that poetry is “a universal language of understanding in which we can all hope to meet”1. This was a belief he had long held, and all his adult life he had a fierce desire to make poetry more popular and more easily available to everyone. In an interview at the Adelaide Festival Book Week in 1976, he spoke of the way in which countries like Hungary or Russia published thousands of copies of poems and how “it’s not a few teachers and fellow-writers that read it, which is the case here, [Australia] and the case in England very largely. It’s everybody every truck-driver has a book of poetry lying around in his cab”2. The problem, as he saw it, was the expensive way in which poetry books were published in England. “Why don’t they publish soft-cover books for book-lovers as they do in France?”, he complained to me in 1992.3 .

Lucas Myers, who first met Ted at Cambridge University in 1954, remembers that even then he talked about the need for cheap poetry publications. One of Ted’s ideas, Lucas says in his memoir, Crow Steered Bergs Appeared, was to “encouraging someone to found a poetry magazine that would be issued in tabloid format and sold for threepence a copy”4. He also talked of establishing two periodicals, each so cheap that anyone could buy them.

Daniel Weissbort, too, remembers that Ted was always full of ideas on this subject. At a New Years Eve party in 1963/4, Ted had a long conversation with him during which he talked in more detail about establishing two journals, one for English poetry (possibly produced so cheaply that it could be made available “at each check-out counter in supermarkets”5) and a second to be “devoted solely to translations of contemporary foreign poetry into English”6. A journal of this second kind suited Daniel’s own particular interests so, encouraged by Ted, he followed up the idea. This resulted in the publication, in October 1965, of the first issue of Modern Poetry In Translation (MPT)7.

There was, at that time, a sudden, growing interest in translations of foreign poetry, and Ted was actively involved in helping to organize the first Arts Council International Poetry Festival, which had also been his own idea. In spite of some resistance to the concept of inviting foreign poets to take part in a British poetry festival, the Arts Council had ultimately agreed to his plans. Daniel recalls that “the first idea was to tie [MPT] in to the international poetry festivals and persuade the festival committee, of which Ted was a key member, to allot money to purchase lots of copies including the programme for ‘free’ distribution. i.e. to budget for this in the cost of the ticket!”8.

Ted, himself, remembered that they toyed with “the fantasy of sending to every known poet – offering to their curiosity – a free copy of each issue”. Unfortunately, that fantasy “evaporated with the first bill”: it was, however, responsible for the format of the first issue: “a flimsy newspaper (the first issue was on rice paper) that would never seem to demand more than a cursory scanning, and wouldn’t much resist being thrown away. Functional, current, disposable – such were our key words”9. So disposable was this format intended to be, in fact, that another fantasy of Ted’s was to print it “on table napkins, so that it became available in cafes and restaurants ensuring that it was at least glanced at by people as they wiped their mouths”10.

Reality soon intervened, because the rice-paper used for the first issue of Modern Poetry In Translation was unexpectedly expensive. “I’ve been thinking all along of a fairly scrappy looking thing”, Ted wrote to Daniel when he saw the first estimates, but “the cost sounds terribly steep”11. Nor was the process of producing the magazine trouble free. By September 1965, Ted was complaining to Daniel and Helga Huws that the magazine was “suddenly emerging to show us its real dimensions – an absolute horror of business, correspondence, sub-officials, agents, & hurry.”12.

Richard Hollis, who was responsible for designing and printing MPT, recalls that the format chosen was that of the pacifist magazine Peace News and that they used the same printer13. In a panel discussion in 2010, Hollis also remembered that he had at that time just returned from South America where “the notion was that you could just hand out poems in the street, and it was free”. This, too, probably influenced Ted’s decisions about MPT.

In the end, that first tabloid-format MPT was printed on thin “bible-paper”, so that it could be cheaply air-mailed, and was priced at two shillings and six pence. Modern Poetry In Translation was, and has remained a success. But even if it did not fulfil all Ted’s dreams, he never gave up his efforts to make poetry more widely available to everyone.

In 1969, perhaps with William Blake’s illuminated books in mind, Ted told Daniel Weissbort that he was thinking of publishing “little editions”, using poems of his own and those of a few friends, and doing them “really beautifully – maybe very small, yes with woodcuts etc. in a small edition and a slightly larger edition, dirt cheap, in proof bound form” 14. Since there were already collectors interested in his own work, he thought that “one issue, signed, and sold for three guineas would float the first three securely”, and he suggested hopefully that the proof bound copies might eventually be sold at a price which would “undersell Penguin”. The germ of this idea would eventually come to fruition but not quite in the way Ted had envisaged, since it soon became apparent that really beautiful productions were never cheap.

Alan Sillitoe, in a memoir written shortly after Ted’s death, tells of a dinner which he and his wife, Ruth Fainlight, had with Ted and his sister Olwyn at Court Green15. Wondering what to do about the deplorable fact that poetry was not “cheaply and more widely available”, the four of them “spent the time over several bottles and a long dinner working out details of the Giveaway Press. Poems were to be printed on the cheapest of paper and sold on street corners for only a penny or two”16. Their reasoning, as Olwyn Hughes recalls, was that “poetry publications could be cheap without the big splendid offices, editors, etc. etc., of such as Faber”. Sadly, they found that this was not true. The main problem was typesetting costs: “Type-setting (this was before computers… ) and paper and binding made a short privately created run very expensive. We would have had to charge as much as a trade publisher but without their huge sales network”17.

Having given up the idea of producing cheap, widespread publications, it occurred to Ted and Olwyn that a possible alternative market for poetry would be fine, limited edition books. Initially, a joint venture between Ted and Daniel Weissbort was planned. Ted provided Daniel and his Viper Press partner, David Ross, with a small collection of Sylvia Plath’s poems for their first publication, but Daniel was slow getting the project under way. So, Ted took back the poems, intending that he and Olwyn would publish them themselves.

Olwyn bought books of instructions from Mr Lawrence, “an aged expert in all things to do with print making and book making, in his ‘Aladdin’s Cave’ in Bleeding Heart Yard. He had been for decades the main supplier to artists and tradesmen of the old crafts. He recommended the specialised books I had on the old craft of bookmaking, still practiced in production of fine editions. … But they launched me on the splendid path of creating books – suiting their contents to the wide variety of hand made and mould made papers, types of binding, choice of backs – paper or leather etc. To the world of typefaces”18.

There is one famous literary precedent for this sort of brother-sister publishing collaboration, as Ted and Olwyn probably knew. Yeats’ elder sister, Elizabeth, had been a member of William Morris’s Arts and Crafts circle and had studied printing at the Women’s Printing Studio in London. In 1908, she founded the Cuala Press in Dublin, where she designed and hand-printed beautiful, fine editions of work by her brother and other Irish writers. It was, as Olwyn noted, a purist press which did its own printing and binding etc.: the Hughes’s used printers and binders, but “only the best we could find, the best paper and top binders”.

Olwyn played the major role in the Rainbow Press Publications. She chose the printer and binder for each edition and mostly chose the paper on which it was to be printed. The hand made, decorative Japanese papers often used as endpapers or in the binding of the books were sent to her from Japan by her friend, Akira Minami, Professor of Literature at Kyoto, who was a scholar and translator of work by Sylvia and Ted.

Ted enjoyed being involved in the making of the books and had enormous creative force and energy. He watched over the Press productions and provided much of the material from his own writings. He was also knowledgeable about fonts, and would browse books of typefaces for pleasure. He had once sent a proof copy of one of Sylvia’s books back to Faber requesting a larger, better typeface than the unsuitable, tiny print which Faber had chosen. And in 1993, when Faber published Three Books, Ted wrote to Keith Sagar that the poems “could not be worse in any other typeface…in future it will be a condition of my contract: typeface”19. So, Ted’s approval was sought for the typefaces used in the Rainbow Press books and he selected a slightly bold Bodoni for his own works, as in the ‘colours of the rainbow’ series, which had also been his idea. The original plan for this special series was to publish sequences of short poems or a short prose passage in a standard format, all the same size (8" x 6"), using Italian mould made paper, similar typeface and bound in calf leather in the colours of the rainbow from indigo to red, but beginning with black and ending with white. Ultimately, only four of this special series were published: Eat Crow, Prometheus on His Crag, Orts and Adam and the Sacred Nine.

The Rainbow Press also had a lot of help from the American artist, Leonard Baskin, who had been a close friend of Ted’s since he and Sylvia had lived in the USA. As Olwyn says, “It was a lucky thing indeed for Rainbow that the Baskins lived in Devon for much of the lifetime of the Press. A superb artist and also a great reader (not always the case with artists), his illustrations for the Rainbow books echoed their text admirably. As though that was not enough, Baskin was a great bookmaker himself with many years experience. His Gehenna Press is a famous one. He provided illustrations for many of [our] books, designed title pages of some, and completely designed Pursuit, for which he provided a superb new colophon”20.

Olwyn also had advice from Sebastian Carter (who with his father, Will, printed just over half of the Rainbow Press titles at The Rampant Lions Press in Cambridge) when he was printing a book. Some of this advice she followed; some she did not, and often regretted it later. He, too, designed “an elegant colophon”, which was used in Lyonnesse.

Others who helped were Keith Gossop, who was a founder member of Rainbow Press and with whom Olwyn was living when it was established. He helped generally with printers and binders; and later, Olwyn’s husband Richard Thomas took charge of all the packing21.

The first publication to appear under The Rainbow Press imprint in March 1971 was Crystal Gazer, which contained twenty-three previously unpublished poems by Sylvia Plath, together with a single line drawing by Plath of one of the “corn vases” which she described in her journal and which is similar to the “boy” she drew there22. The drawing, which resembles a black-and–white lino-cut, shows a peasant girl in a European costume with her apron spilling vegetables, and a large, wicker collecting basket over her shoulder.

In an informative article about the Rainbow Press, Sebastian Carter comments that the first three titles (two of which were printed by the Daedalus Press in Norfolk) “had fairly ambitious runs of 300 to 400” books23. Of this, Olwyn says: “I was keen to try out a variety of bindings etc. – I had Sangorski24 do exquisite vellum binding in a solander box and a number bound in morocco. Too long a run and too much variety of binding were the lessons of CG. And of Lyonnesse (similarly long and various).But I did learn a lot in the process. Choosing the right binding(s), the best typeface, the perfect paper the right printer and binder for each book was quite a creative enterprise. Having all those splendid craftsmen to draw on (and to meet) was a delight… The most enjoyable thing I’ve ever done”.

Having all those splendid craftsmen to draw on (and to meet) was a delight… The most enjoyable thing I’ve ever done”.

The second book, Poems, which appeared at the same time as Crystal Gazer contained eighteen uncollected poems by Ted, Ruth Fainlight and Alan Sillitoe, each of whom provide six poems. Ruth and Alan had been friends of Ted’s since he and Sylvia met them in 1960. Ruth’s brother, Harry, is the subject of Ted’s poem ‘To Be Harry’ (THCP 629). Embossed in real gold on the cover of this sumptuous book is an image of Isis: Magnae Deorum Matris. This was chosen by Ted and it is the same ancient image as hung in Ted’s and Sylvia’s flat and which Sylvia once described in a letter to her mother as “a lovely engraving of Isis from one of Ted’s astrological books” (SPLH 7 Feb.1960).

The third book published in 1971 was Lyonnesse, which contained twenty-one previously unpublished poems by Sylvia Plath. A note inside the book indicates that a few of the poems would shortly be published in Winter Trees by Faber and Faber, London, and Harper and Row, N.Y. It is also noted that “two of Sylvia Plath’s manuscripts slightly enlarged form the end-papers in copies 1-100 only”. One of these hand-written drafts was of the title poem, ‘Lyonnesse’; the second, which was advertised as being in the first 10 vellum bound copies only, was of Sylvia’s poem, ‘Child’.

Eat Crow, the fourth Rainbow Press publication, appeared in November 1971. This small, slim, black volume was the first of the planned series of ‘colours of the rainbow’ books. It is described in the Rainbow Press flyer as being the “first printing of a dramatic interlude” and it contains part of the script of Difficulties of a Bridegroom, a play which Ted had begun to write in 1965, and parts of which he had recently used with Peter Brook’s company of actors as improvisation exercises during their preparation for the performance of Orghast at the Shiraz Persepolis Festival25. Unusually, the flyer for this publication states that “There will be no subsequent trade edition”.

Eat Crow is a surreal, nightmarish journey into the dark, chaotic otherworld of the human subconscious. In 1965, Ted had extracted a long passage from it to be published in the magazine, Encounter, as ‘X’26. Early in 1971, the first part of this passage became the title poem of Crow Wakes, a Limited Edition book of poems which, according to its publisher, Alan Tarling of the Poet & Printer Press, were, as Ted had told him, poems which had been excluded “for personal reasons” from Crow: The Life and Songs of the Crow, which Faber had published in 197027.

Eat Crow is not the same as the play entitled Difficulties of a Bridegroom which was broadcast by the BBC Third Programme in January 1963, but both were part of a longer play of that title. In a note amongst manuscripts in the British Library, Ted wrote of Difficulties of a Bridegroom as “A stage play which had the sub-title ‘a marriage in 17 murals’ ”28. He described it to Ekbert Faas in 1970 as “a long waddling verse drama… partly based on Andreae’s The Chemical Wedding of Christian Rosencreutz”29 and, as he told Faas, the extract from Eat Crow (which had been published as ‘X’ and ‘Crow Wakes’) was originally “a speech made by the bride’s father who at the end of the day was petrified in a glass case. It’s his account of how he got into that condition”30.

Eat Crow, ‘X’ and the poems in Crow Wakes are not an obvious part of the Crow story but they, like Crow, explore an horrific, amoral world of death, demons and animal energies which, in many ways, reflects the demonic visions of the Buddhist Bardo which are so vividly described in the Bardo Thodol – Tibetan Book of the Dead. Yet, this world of Eat Crow is our world, the world which Ted described in his 1959 libretto for the Bardo Thodol as the Buddhist “Wheel of Blood”: a world “Bound by evil Karma, bound by terror and longing / Resisting Grace”31. Into this deathly world in Eat Crow, comes a crow which, despite its “terrible black voice” is described in the play as “a sign of life” which “has come up from the maker of the world”.

1971 had been a busy year for the Rainbow Press. Each of the four publications required a great deal of work and then had to be sold. Olwyn remembers that there had been no special plan as to when a new book would appear but “Ted would just turn up with poems and say ‘Here’s another book’”32. The next Rainbow Press publication, Prometheus On His Crag, did not appear until November 1973.

Prometheus On His Crag was the second in the rainbow-coloured series and it is described in a Rainbow Press brochure printed in 1974 as being “in size and design… a twin volume to EAT CROW”. Of the 21 “new poems” in the book, three were excluded from the sequence published in Faber’s trade edition of Moortown in 1997, where three different poems were added33. The sequence published in Faber’s Ted Hughes: Collected Poems in 2003 is that which appeared in Moortown and the three excluded poems are published in full in the Notes (pp. 1259-9)34.

Pursuit, described as “A first edition of fifteen uncollected poems (with one exception)” by Sylvia Plath, appeared just four months after Prometheus On His Crag, in March 1974. This book was larger than those of the rainbow-coloured series and, because of its publishing history, Sebastian Carter described it as “a curious hybrid”35. Baskin not only designed the book (which was contrary to the Rampant Lions Press’s usual policy of designing everything they print), he also chose the typeface and he designed the hand-lettered title page36.

September and November 1974 saw the publication of two more books: Spring Summer Autumn Winter, which contained twenty of Ted’s poems; and Mandrakes by Thom Gunn. Neither of these books was part of the special rainbow-coloured series, and each was highly distinctive in size and binding.

As is noted in Spring Summer Autumn Winter, five of the poems had already been published “in a small paper-bound edition” by Richard Gilberton of Bow, Devon, as Five Autumn Songs for Children. These had been written for, and sung at, the Little Missenden Harvest Festival in 1968.

Mandrakes, which appeared just two months later, contained ten new poems by Thom Gunn. Ted had know Gunn for some time. In 1962, Faber had published Ted Hughes and Thom Gunn together in Selected Poems with Thom Gunn, and in August 1962 Ted, Sylvia, Thom Gunn and Peter Porter had been recorded together as part of the series, The Poet Speaks, which was produced by the Lamont Library at Harvard University. Then, in 1963, Ted and Thom collaborated as editors of the Faber publication, Five American Poets. Christopher Reid, as editor of Letters of Ted Hughes, notes that although at the time Ted and Thom “were in no sense allies”, they later grew friendly37. Baskin provided five illustrations for this book.

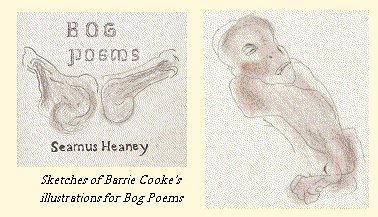

The ninth Rainbow Press book, Bog Poems by Seamus Heaney, was completed and published in May 1975. The illustrator, Barrie Cooke, was a friend of Heaney’s and a long-time naturalist and fisherman friend of Ted’s. His distinctive images of bones and a bog-man, in charcoal and red-brown pigments, are a perfect accompaniment to Heaney’s bog poems. Heaney, in his ‘Foreword’, writes that the linguistic origins of the word ‘bog’ are from the Norse word meaning ‘soft’; and where he grew up in Ireland the bog was called “the Moss”. These new poems, he says, “raised their heads out of my own ground”.

All eight poems were later included in the Faber trade edition North in 1975, but Heaney dedicated the poems in the Rainbow Press book to Ted and Olwyn Hughes and Barrie Cooke for their “nurturing interest” in them. In 1975, Heaney was still a young poet, ten years younger than Ted, whose book, Lupercal, had first inspired him to seriously write poetry, but the two men became firm friends.

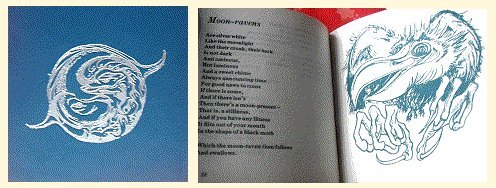

Earth-Moon, the next Rainbow Press publication, was unique in that Ted illustrated it himself. The book was small (5½ x 5½) and the two editions had the most beautiful and unusual covers. Olwyn chose a tiny, rounded, 9pt, Century Bold Schoolbook type for the poems and Sebastian Carter, who designed and printed the book, used blue and slate-blue inks for these on hand-made paper.

Ted’s ten drawings of moon-creatures are as imaginative as his poems. Four great, clawed, lizards, for example, surround a sliver of moon in the middle of ‘Moon-walkers’; A big-beaked raven, surprisingly benign looking in spite of its fearsome claws, crouches opposite ‘Moon ravens’; a dappled snake coils tightly around a quarter moon at the end of ‘Moon-bells’ (a poem which incorporates some of Ted’s favourite parables); and a strange, distorted, spiked creature illustrates ‘Moon-thorns’. A dragon-like moon-monster lifts its head to a quarter moon from its mountainous home at the end of ‘Singing on the Moon’; and ‘Moon-mares’ has a picture of wild, rearing, flame-borne horses to accompany it.

The copy held by the British Library is inscribed by Olwyn to Leonard and Lisa Baskin for Christmas 1976, and inside the back cover is a hand-written extra poem and a drawing of “a lunar lune” by Ted.

Two years elapsed before the publication of Orts in the Spring of 1978.

The word, ‘Orts’, is a dialect word meaning ‘leavings’, and the Rainbow Press flyer describes the book as “A first edition of 63 poems many of which were written for the second part of Gaudete (Faber 1977) but not included therein”. In fact, 19 of these poems were written in 1973-4 and were inspired by Ted’s reading of A.K. Ramanujan’s translations of sacred Southern Indian vacanas in his book Speaking of Siva38. Of the 96 poems Ted wrote at that time, 18 appeared in the Epilogue of Gaudete, 19 in Orts, and the rest remain unpublished39. The size of the book and the style of binding conform to the pattern of the rainbow-coloured series, and Baskin’s illustration of a human face inside a rat’s head makes a dramatic Frontespiece.

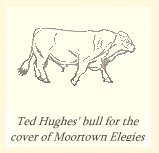

Moortown Elegies, which was published that same year (in October 1978) was a very personal book, dedicated to the memory of Carol Hughes’ father Jack Orchard, with whom Ted had farmed Moortown Farm40. On the cover, blocked in gold, is Ted’s own drawing of a bull; and the Baskin drawing (which is placed opposite the poem ‘Hands’, which Ted had written in remembrance of Carol’s Father) is inscribed “For Carol”. It contains “35 mostly unpublished poems and passages” from a verse journal which Ted had kept while farming in Devon.

Moortown Elegies, which was published that same year (in October 1978) was a very personal book, dedicated to the memory of Carol Hughes’ father Jack Orchard, with whom Ted had farmed Moortown Farm40. On the cover, blocked in gold, is Ted’s own drawing of a bull; and the Baskin drawing (which is placed opposite the poem ‘Hands’, which Ted had written in remembrance of Carol’s Father) is inscribed “For Carol”. It contains “35 mostly unpublished poems and passages” from a verse journal which Ted had kept while farming in Devon.

Just four months later, in February 1979, Adam and the Sacred Nine, the fourth and last book in the rainbow-coloured series, was published. The poems chart a cabbalistic journey which ends with the awakening of Adam and opposite its title page is Baskin’s drawing of a phoenix rising from its fiery nest.This is the same image as that which appears as an end-plate in the 1979 Faber trade edition of Moortown.

Next, in April 1979, came Remains of Elmet, which is described in the flyer as “62 new poems about that part of the Yorkshire Pennines, close to Bronte country, where the author spent his boyhood. The area was once part of the ancient kingdom of Elmet”. The flyer went on to note that there were “certain textual differences and one long poem not included in the coming trade edition”.

Remains of Elmet is dedicated to Ted’s mother, Edith Farrar, and the Rainbow Press edition contains four photographs by Fay Godwin. Sebastian Carter chose the Stellar Press at Hatfield to reproduce these photographs and Fay Godwin thought “the photo-reproduction in Rainbow very fine (better than Faber)”41.

The Faber trade edition of Remains of Elmet, which appeared in October of 1979, contained all but one of the poems in the Rainbow Press edition (‘Wycollar Hall’) but in a slightly different order, together with sixty-three of Fay Godwin’s photographs.

The third Rainbow Press publication in 1979 was the slim, hand-stitched booklet containing the text of Ted’s tribute to Henry Williamson, which Ted had given at the Service of Thanksgiving in the Royal Parish Church of St Martin-in-the-Fields on 1st December 1977.

In 1977, Ted wrote to his brother, Gerald, that this address was “a sort of tribute” which he had “once read… at a little celebration” whilst Williamson was still alive, and Williamson’s daughters had asked him to read it again at the Memorial Service42. In his tribute, Ted spoke of Williamson as having been “an essential and precious part of my life, in some ways, a crucial part”. Ted had found Williamson’s book, Tarka the Otter, in his school library when he was an eleven-year-old, and he had read it so often that he almost knew it by heart. “It entered into me”, he said,” and gave shape and words to my world as no book ever has done since.” And he spoke of it as “something of a holy book, a soul book”… “an enchantment which lasted for years and gradually crystalised into an ambition to write for myself”43.

The last Rainbow Press publication, Dialogue Over a Ouija Board, a verse drama by Sylvia Plath, was published in September 1981. Leonard Baskin thought this book “the best of all the Rainbow books”44 and Sebastian Carter, who designed and printed the book, called it “quite delicious”45.

Baskin’s drawing of a faun’s head, which is opposite the title, looks very much as one might expect Ted’s and Sylvia’s Ouija spirit, Pan, to look. Pan, at different times, had led Sylvia to write her poem ‘Lorelei’, and Ted to write ‘An Otter’46.

The text of Dialogue Over a Ouija Board, according to Ted’s note in Sylvia Plath: Collected Poems (where it is reproduced in full), was written by Sylvia some time in 1957-8 and uses “the actual ‘spirit’ text” of one of their Ouija sessions47. At this particular session only Ted and Sylvia (and the ‘spirits’: Ted enclosed the word in inverted commas) were present. However, at a different Ouija session, Pan’s words, as quoted by Ted in his Birthday Letters poem, ‘Ouija’, were actually the words of their friend Daniel Huws, who had got tired of waiting for spirits to move the glass on the Ouija board and had guided it himself. He comments that he had no idea what he was going to say, so, of course, he might have been controlled by Pan. Ted certainly believed that48.

Over the ten years between 1971 and 1981, the Rainbow Press published sixteen beautiful books. By 1981, however, Olwyn no longer had the help of Keith Gossop or Richard Thomas. The use of part-time packers proved to be unsatisfactory and Olwyn did not have time to pack the books herself. So, in spite of the fact that for both Ted and Olwyn the press had been a happy experience, Olwyn decided reluctantly not to publish any more books. Looking back, she wrote, “The fine work had a good audience and many friends in collectors… It was a lovely thing to do. It never made much cash as the profits were ploughed back into further publications”. But profit was not the motive behind the books: “they were never more than a help in that instance but spread the various poets' work around in their special ways”49. Olwyn’s biggest regret is that when Ted brought Howls and Whispers to her in 1997 and asked her to publish it, she decided not to take it on. It was published "very handsomely" by Baskin as a limited edition in 1998, at his Gehenna Press.

In 1979, the Rainbow Press books were included in a special exhibition of Ted’s illustrated poems at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London50. For this exhibition, Leonard Baskin supplied a drawing and Ted wrote the poem, ‘In the Black Chapel’. Both of these were used on a special poster; and Baskin’s drawing was also used on the front of the catalogue.

Although there were no more Rainbow Press publications after 1981, the Hughes family were still actively involved with small press publications. Olwyn had bought a small Albion press in the early 70s intending, she says, to play around with “design ideas… mainly of title pages”. Had she come up with anything she would have “sent such roughs to a good printer as suggestions51”. When the printing turned out to be more complicated than she expected, she gave the press to Ted’s son, Nicholas, who had learned printing and bookbinding at school and was exceptionally good at it.

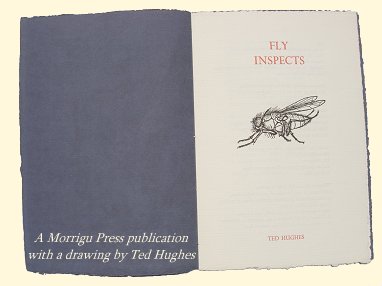

In 1979, Nicholas set up The Morrigu Press. He bought more type and began to produce limited copies of Ted’s poems as broadsheets and small booklets, printing them himself on hand-made paper, encasing some in a decorative hand-printed, Japanese-paper folders, and sewing others into hand-made paper covers. One of Nicholas’s Morrigu Press publication, Pan, was illustrated by his sister, Frieda, with two scorpions. Many others contained drawings by Ted. The last few editions of booklets also included a colophon of a three-legged crow, drawn by Leonard Baskin from a design sketched out to him in a letter by Ted: “The main things are: Raven, 3 legs, a sun (it’s Chinese sublimation of the 3 headed Morrigu who was a moon bird)”52.

Ted’s drawing skills were excellent. A number of his drawings were on display at the V & A exhibition in 1979, but his only published drawings appear in the Rainbow Press book, Earth Moon, the Morrigu Press publications and, as a single drawing of a bull, on or in Moortown Elegies and the trade edition of Moortown Diary. In conversation with me, Ted once said that Leonard Baskin had dissuaded him from illustrating his own books, but he frequently drew on cards, postcards and inside the books which he gave to friends. Reg Lloyd’s wife, Louise Macmillan, has a copy of What is the Truth (the Faber edition of which was illustrated by Reg) which was extensively ‘lionised’ by Ted over a number of visits, with drawings of his birth-sign lion in various imaginative forms in many of the margins.

Nicholas’s Morrigu Press publications sold for between £15 and £28, a small sum for the hours of painstaking work involved, the cost of materials, and the risk that not all of any edition would sell, although Olwyn notes that they knew their market and the broadsheets were simple to do. Sixteen Morrigu Press publications appeared between 1979 and 1983, after which, Nicholas received his BA degree in Zoology and, in 1984, moved to Alaska to take up a position as research assistant at the Alaska Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit. Nicholas’s Albion handpress was left behind in Devon and the Morrigu Press publications came to an end.

List of Rainbow Press publications.

List of Morrigu Press publications.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

1. Weissbort, D. Ted Hughes and Translation, Richard Hollis, Five Leaves Publications, Nottingham, 2011. p.7.

2. Interview of Ted Hughes at the Adelaide Festival Book Week. Transcript: .//Adelaide3.htm.

3. Ann Skea notebooks and diaries, British Library Dep. 10515. Notebook 1992.

4. Myers, L. Crow Steered Bergs Appeared, Proctor’s Hall Press, Sewanee, Tennessee, USA, 2001. p.57.

5. Daniel Weissbort, e-mail to Ann Skea, 6 Oct. 2009.

6. Daniel Weissbort, unpublished memoir. In Ted Hughes and Translation (op.cit.) Weissbort dates the New Years Eve Party as 1962/3. The true date is uncertain.

7. The October date is specified in a letter from Hughes to Charles Tomlinson. Reid, C. (Ed.). Letters of Ted Hughes, Faber, 2007. Summer/Autumn 1965. p.247.

8. Daniel Weissbort, e-mail to Ann Skea, 12 Oct. 2009.

9. Hughes, T. ‘Introduction’, MPT 1982, in Weissbort, D.(Ed) Ted Hughes: Selected Translations, Faber, 2006. p. 204.

10. Daniel Weissbort, unpublished memoir.

11. Hughes to Weissbort, 12 Feb. 1964 in Reid (Ed.), Letters of Ted Hughes, op.cit., pp.231-2.

12. Hughes to Daniel and Helga Huws, 26 September 1965 in Reid (Ed.), Letters of Ted Hughes, op.cit., p.249.

13. Peace News, founded in 1936 was, until 1961, the official paper of the Peace Pledge Union. Gandhi was an early contributor. Coincidentally, the editor of Peace News when MPT was being founded was Theodore Roszack, whose work, like Ted’s, was published by Faber & Faber. There is no record of the two men ever meeting.

14. Hughes to Weissbort, Autumn 1969 in Reid (Ed.), op.cit., pp.297-8.

15. Sillitoe’s 1970’s date for this meeting is probably incorrect, since by 1970 work had already begun on the first of the Rainbow Press books. It is likely, too, that the dinner was not at Court Green but at Olwyn’s London home. Olwyn moved from Court Green back to London in October 1965, although she still visited Devon frequently until about 1970.

16. Sillitoe, A. ‘Ted Hughes: A Short Memoir’ in Gammage, N (Ed.), Epic Poise, Faber`1999. p. 260.

17. Letter from Olwyn Hughes to Ann Skea, 18 Nov. 2009.

18. Letter from Olwyn Hughes to Ann Skea, 5 Dec. 2009.

19. Correspondence of Ted Hughes and K. Sagar. British Library. Add.78756. 27 April 1993.

20. Letter from Olwyn Hughes to Ann Skea, 7 Jan. 2012. Baskin’s new colophon replaced the Press’s original ‘Moon-ark’ emblem which has been attributed to William Blake and which first appeared at the end of Bryant’s New System of Mythology, (1774-6). cf. Raine, K. William Blake, Thames and Hudson, London, 1970. pp. 13-14.

21. Richard Thomas and Olwyn divorced and Richard died in Crete in 1984. In a letter to Leonard Baskin, Ted wrote that “he died of bloodloss (he was a haemophilic) when some ulcer ruptured”. Leonard Baskin/Ted Hughes correspondence. British Library Add mss. 83685. Thomas had Haemophilia B, a mild form of Haemophilia sometimes called the ‘Christmas disease’.

22. Kukil, K (Ed.), The Journals of Sylvia Plath, Faber, London, 2000. ‘Appendix II 26[b] – 27[a]’, pp. 613-4.

23. Carter, S. ‘The Rainbow Press’, Parenthesis, 12, November 2006. pp. 32-5.

24. Sangorski and Sutcliffe (est. 1901) are one of London’s oldest and most prestigious bookbinding companies (See: https://www.bookbinding.co.uk/History.htm). They were Olwyn’s preferred bookbinders .

25. In July and August 1971, Hughes was with Peter Brook’s company in Tehran. Smith, C.H. Orghast at Persepolis, Eyre Methuen, London 1972. p.154.

26. Encounter, (25:20-1) July 1965.

27. Sagar and Tabor, Ted Hughes: A Bibliography 1946-1995, Mansell, 1983, p. 58.

28. British Library Add. mss. 53784: Ted Hughes and Sylvia Plath: verse and prose.

29. This book is an alchemical text written by the 17th century Hermeticist, Johann Christian Andreae.

30. Faas, E. The Unaccommodated Universe, Black Sparrow Press, Santa Barbara, 1980. p.212.

31. Weissbort, D., op.cit., pp.5-6.

32. Conversation with Ann Skea, 9 August 2011. Diary/Notebook 26.

33. Moortown, Faber, London, 1979. pp.71-92.

34. Kegan, P. (Ed.) Ted Hughes: Collected Poems, Faber. London, 2003.

35. Carter, op.cit., p.33.

36. Carter, op.cit., p.33.

37. Reid (Ed.), op.cit., p. 201.

38. Ramanujan, Speaking of Siva, Penguin Classics, 1973.

39. Skea, A. Ted Hughes: Difficulties of a Bridegroom, Unpublished paper read at the Ted Hughes Conference at Pembroke College, Cambridge, in 2010.

40. Jack Orchard died in February 1976, after which Ted and Carol sold much of their farm stock and let the fields for agistment.

41. Letter from Olwyn Hughes to Ann Skea, 18 November 2009.

42. Letter from Hughes to Gerald and Joan Hughes, 28 November 1977 in Reid (Ed.), 0p.cit.. p. 387.

43. Years later, Ted wrote of the influence of Williamson’s book in a letter to Keith Sagar, 18 July 1998. Reid (Ed.) Letters of Ted Hughes, Op.cit.. pp.724-5.

44. Letter from Olwyn Hughes to Ann Skea, 5 December 2009.

45. Carter, op.cit., p.34.

46. Kukil, K. (Ed.), The Journals of Sylvia Plath, Faber, 2000. ‘Friday July 1958’, pp. 400-401; and Reid (Ed.), op.cit., p.721.

47. Hughes, T. (Ed.) Sylvia Plath: Collected Poems, Faber, London, 1981. pp. 276-286. See also Ted’s accounts of Ouija in letters to Lucas Myers (16 November 1956) and Keith Sagar (18 July 1998) in Reid (Ed.), op.cit., pp.87-8 and p.727.

48. Conversation with Ann Skea, 16 September 2010. Diary/Notebook 25.

49. Letter from Olwyn Hughes to Ann Skea, 18 November 2009.

50. Illustrations to Ted Hughes Poems, The Library, Victoria and Albert Museum, 12 September to 28 October 1979.

51. Letter from Olwyn Hughes to Ann Skea, 17 May 2011.

52. Correspondence of Ted Hughes and L.Baskin. British Library Add. 83684. Box.3. 19 July 1977.