Conjunction, Crystallisation, Projection

Once Mercury and Sulphur (now known as the Red Male and the White Female1) have been extracted from the original alchemical mixture and purified, they must be recombined, because ‘Perfect Mercury, for the generation of the work, has need of a female’2.

In Norton’s Ordinal of Alchemy we can read the usual alchemical metaphor for this process:

Then is the faire white woman Mariede to the rodie mane3.

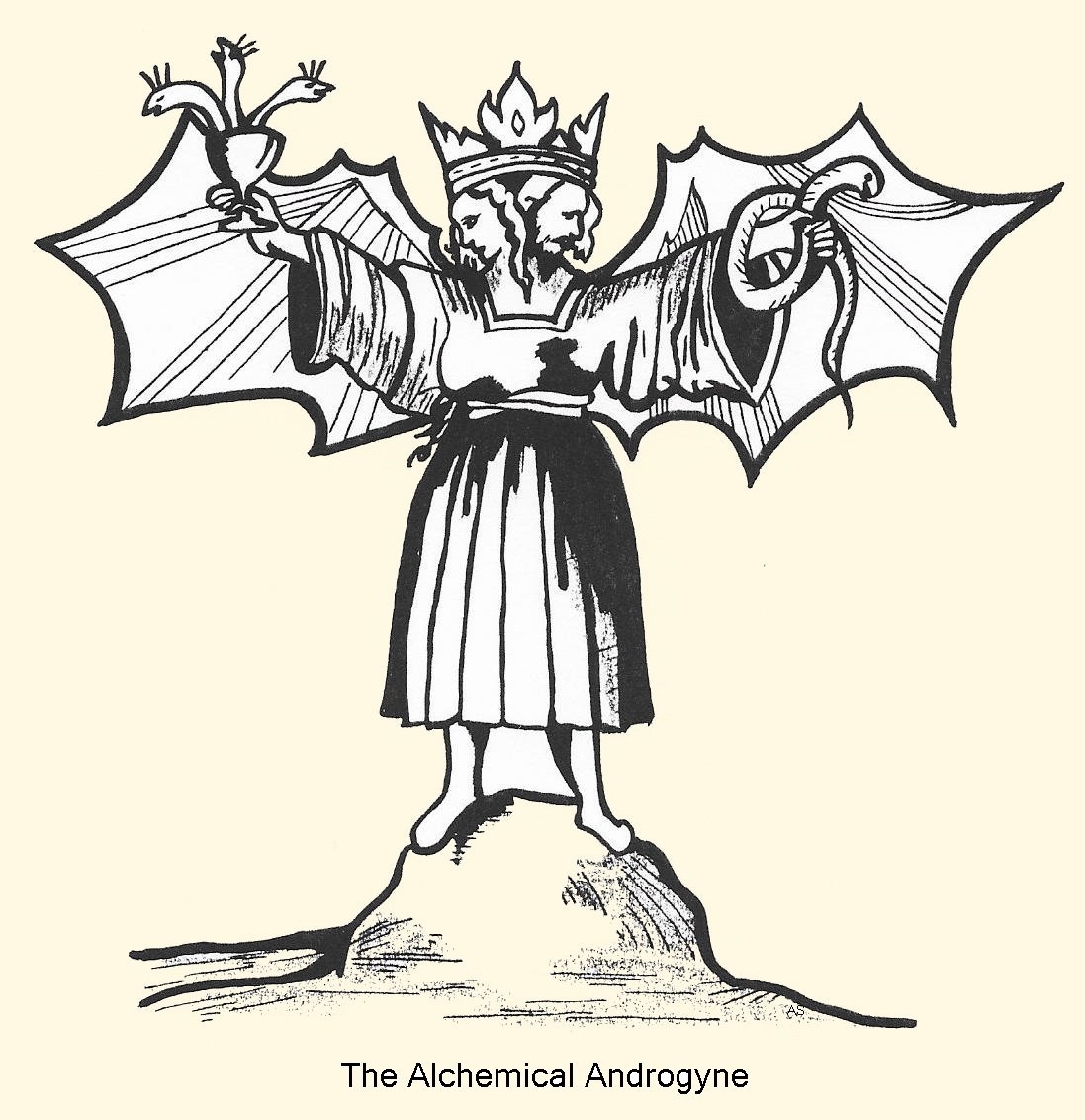

On symbolic, psychiatric and material levels this next stage of the alchemical process entails, as the metaphor suggests, the marriage of opposing elements male/female, body/soul, mercury/sulphur. This ‘Conjunction’, or ‘Chemical Marriage’, is described by both Burckhardt and Jung as the central symbol of Alchemy, and it is more complex than a simple uniting of opposites.

The Chemical Marriage, like all other alchemical processes, occurs more than once in the sequence of alchemical events, and this repetition is paralleled in Hughes’ sequence of poems. So, ‘The gatekeeper’, ‘The riddle’, ‘His legs ran about’ and ‘Bride and groom lie hidden for three days’ each present a marriage of opposites. In each poem the elements (both alchemical and human) become progressively purer until, in this final alchemical stage, a perfect union is achieved and the alchemical goal attained.

On the spiritual level, early Alchemists such as Gerhard Dorn explained the first conjunction of the final alchemical stages as the union of soul and spirit, a mental union which follows the overcoming of the body4. ‘A riddle’ (CB.44), in the Cave Birds sequence, describes just such a ‘marriage’ – one which is, in Hughes’ words, “the opposite of a physical marriage”. Following this, however, the process must be repeated for, as Dorn writes:

This first union does not yet make the wise man, but only the mental discipline of wisdom. The second union of the mind with the body shows forth the wise man …(MC.476).

The second union, in Cave Birds, occurs in ‘His legs ran about’. Psychologically, Jung interprets this second union as a necessary recombination “of the spiritual position with the body” so that insights gained by “confrontation with the shadow” (or examination of the sub–conscious) may be “made real” or objectified and used(MC.476). Burckhardt, in his chapter on the ‘Chemical Marriage’, criticises this interpretation and points out that although such an “‘integration’ of unconscious powers of the soul into the ego-consciousness” is necessary, in alchemical–spiritual terms it leaves the process incomplete, because it produces precisely the ego–centred state from which the Alchemist has been striving for release. What is left out by such a description is the creative power, the “Divine ray” or “Pure Spirit”, and it is this which brings the marriage to perfection and completes the whole work5. In the alchemical process, this divine creative power is the sun, the energy of which is present in the fires of the Alchemist’s furnace.

Initially, the second conjunction of the pure red and white elements (the results of the earlier procedures) is fuelled by the natural generative fires of the mixture itself, for which the alchemical metaphor is sexual energy. From this union there emerges a pure crystalline substance, a gem, which must be subjected to the fierce sun–fires of the furnace (the ‘fourth degree of fire’, ‘destructor sensus’ (destroyer of the senses)6 to test its perfection. Now, if all is well, there appears

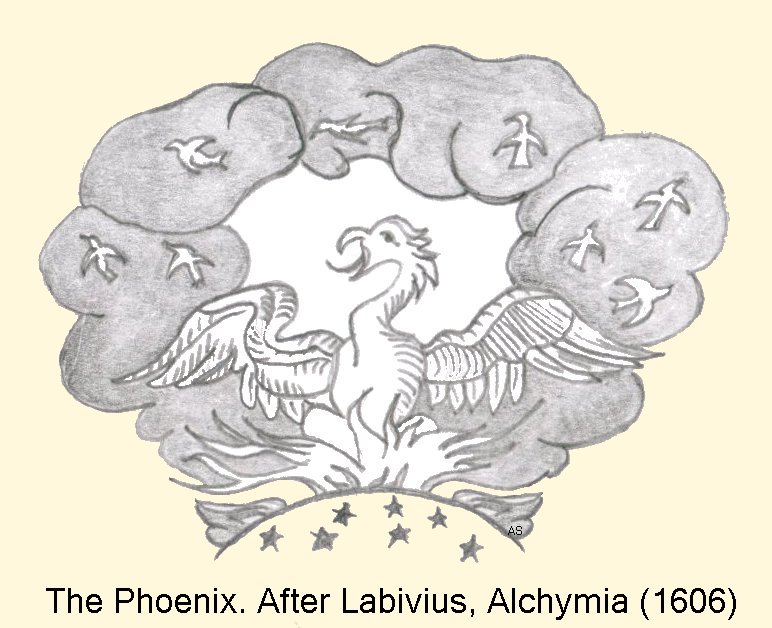

the Phoenix, the strange flashing white jewel, the flower, the expanding feathers of white fire7.

The Phoenix is the alchemical symbol for the complete transmutation. It precedes, with a display of brilliant colours, the appearance of the ‘incorruptible elixir’, the True Stone, the Quintessence which can transmute base material into gold and in which, finally, “the four elements are by our masterie joyned, knitt and united together one with another”8.

In the Cave Birds sequence, the poems from ‘His legs ran about’ to ‘The risen’ comprise the final stage of the alchemical process. They are full of the imagery of fire and light, and a mood of awesome wonder and delight builds progressively towards the climax of ecstatic release when, in ‘The risen’, the eagle soars, free and powerful, across the face of the sun.

The ‘conjunction’ which takes place in ‘His legs ran about’ is fuelled by sexual energy. It results in the rebirth of the protagonist in a state of ‘bare’ purity which frees him from all the influences of the material world around him. In this state he is able to meet the female on an equal basis, and together they begin to rebuild their material bodies and their new relationship, using the sun to test the perfection of each stage. Heralded by the appearance of the terrifyingly beautiful ‘owl flower’, a sun–bird which emerges phoenix–like from the fiery flames, there comes the ultimate spiritual transcendence. The protagonist embodies divine powers and soars free of the Earth to fly in the realm of the sun.

So, the divided elements of the Earth and of Mankind are eventually purified, recombined and divinely illuminated; and the alchemical work is complete. Yet, Mercurius is always elusive and the soul “always inclines to the body” and is ready to “slip back into its former unconsciousness without taking with it anything of the light of the spirit into the darkness of the body”(MC.522). The illuminated one, the alchemical gold, can be of value to humankind only by being brought into contact again with the unregenerate, worldly, base material. Psychological insights, too, are easily forgotten. Consequently, the alchemical process is never truly finished, but must be, like its constituent procedures, constantly repeated.

The vision of the earthly woman revives more strongly, and he is no longer entirely unborn, though not completely born either, with consequent confusions.

In theology, in Alchemy and in psychology, a true guide invariably leads the seeker to the ultimate goal by the way of knowledge, acceptance and, most importantly, love. Love is foremost in the final reintegration of the elements, whatever their nature, because love has the ability to ‘marry’ disparate entities and channel their conjoint powers into harmonious and productive paths.

In myth and in early theogenies, the mating of Heaven and Earth, or of their godly or human representatives, explained and controlled the origin, fertility and continuance of the material world. Even today, sexual union is regarded as important in most religions, either being viewed as a necessary and valuable expression of sacred energies (as in Tantric and Taoist thought) or as a profane and unwelcome distraction from them (as in some forms of Christian and Buddhist asceticism). In either case, there are generally rigorous and specific rules governing the sexual act, which suggests a common apprehension of the powerful and dangerous nature of the energies involved.

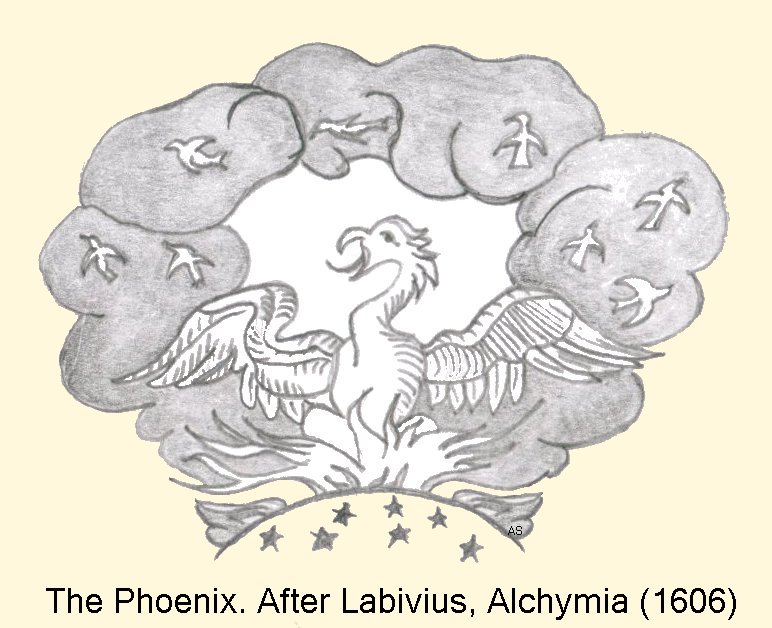

The stage which has now been reached in the Cave Birds sequence parallels that of the ‘Chemical Marriage’ or ‘Conjunction’ of the alchemical elements. This stage marks the beginning of the ‘Major Work’ in Alchemy, and it is dominated by the astrological sign of Venus, Goddess of Love9. The sexual connotations of the conjunction were emphasised in Alchemy by the metaphors used to describe the procedure, as is evident in the many alchemical illustrations showing the copulation of a naked king and queen in a liquid medium. They were, also, carried through into the lives of the Alchemists themselves, where the guidance and help of a female partner (a soror mystica) was considered essential to the work. The writings of the alchemists Thomas Vaughan and Nicholas Flamel, for example, indicate the important role played by their wives, and Kathleen Raine and others who see alchemical parallels in the art and writing of William Blake also point to the involvement of his wife, Catherine, in that work.

Love, however, is not completely defined by the physical act of coition. There is also an emotional/spiritual aspects to it; a joyous, expansive outflow of energy which can be shared without physical contact.

The separation of one aspect from any other, like the separation of our inner and outer worlds, would run counter to the whole pattern of Hughes’ thought and his avowed purpose of working towards unity and balance. So, when the ‘Scarecrow Swift’ guides the Cave Birds protagonist into the way of love, all of love’s aspects are encompassed, and this poem attempts to describe this experience.

Beginning with the poem’s title, which carries its energy on into the opening lines, Hughes uses the rhythm and flow of words and images to capture the driving urgency of desire. The bodies tangle, “trip”, grope and push towards each other, but there is also a sense of timelessness and fulfilment conveyed by certain words (“forever”, “finally”) and by unpunctuated repetitions (“at last at last”, “deeper deeper”). As each part of the body is dealt with, action is followed by gratification and active ‘masculine’ words give way to softer ‘feminine’ ones: the “tangled” bodies become “enwoven”, and the man’s hard “chest” meets the woman’s soft “breast” and rests there “at the end of everything”, its needs met.

Opposites join in words, imagery and mood to create a harmonious unity and, like Yin and Yang, they belong to each other, the one mirroring every aspect of the other “like a mirror face down flat on a mirror”. This mirror image is important in alchemical, Taoist and Buddhist teaching. Philosopher and Alchemist, Ibn Arabi, wrote: The world of nature consists of many forms which are reflected in a single mirror – nay, rather that there is a single form reflected in many mirrors10.

This is a statement of the Hermetic rule that “whatever is below is like that which is above, and whatever is above is like that which is below, to accomplish the miracle of the one thing”11, and alchemical illustrations of the copulation of the Red King and White Queen make the same point by showing them suspended at the surface of a reflective pool.

An even more important aspect of mirrors is mentioned by Jean Cooper in her study of Chinese Alchemy. She writes:

A mirror hanging face-downwards in a temple establishes an axis of light by which the soul can ascend heavenwards, but as reflected light it also represents the manifest world of illusion. In this way the mirror also combines the two great powers; it is the reflected light of the moon, known as the ‘golden mirror’, and at the same time the disc of the sun 12.

Like Yin and Yang, the man and woman in Hughes’ poem are a necessary and natural part of a whole, and the dynamics of their separation and their drive towards unity are those of Nature. Hughes expresses this in his choice of similes: each part needs the other

Like a bull pushing towards its cows, not to be stayed

Like a calf seeking its mama

Like a desert staggerer, among his hallucinations

Seeking the hoof-churned hole

Union brings peace and stillness, and “such greatness and truth”, which descend like a blessing.

Once more the protagonist is re–made and the male and female halves of his nature combined. With images of a starlit grave and a new and tiny world rushing through space, Hughes now links Heaven and Earth and gives the protagonist’s experience a cosmic framework so that, despite his tiny and raw state, neither he, nor we, feel any sense of confinement. Instead, there is a feeling of “astonishment” and exhilaration; of being part of a vast and energetic universe. Inner and outer worlds have been reconciled and a moment of complete unity has been achieved.

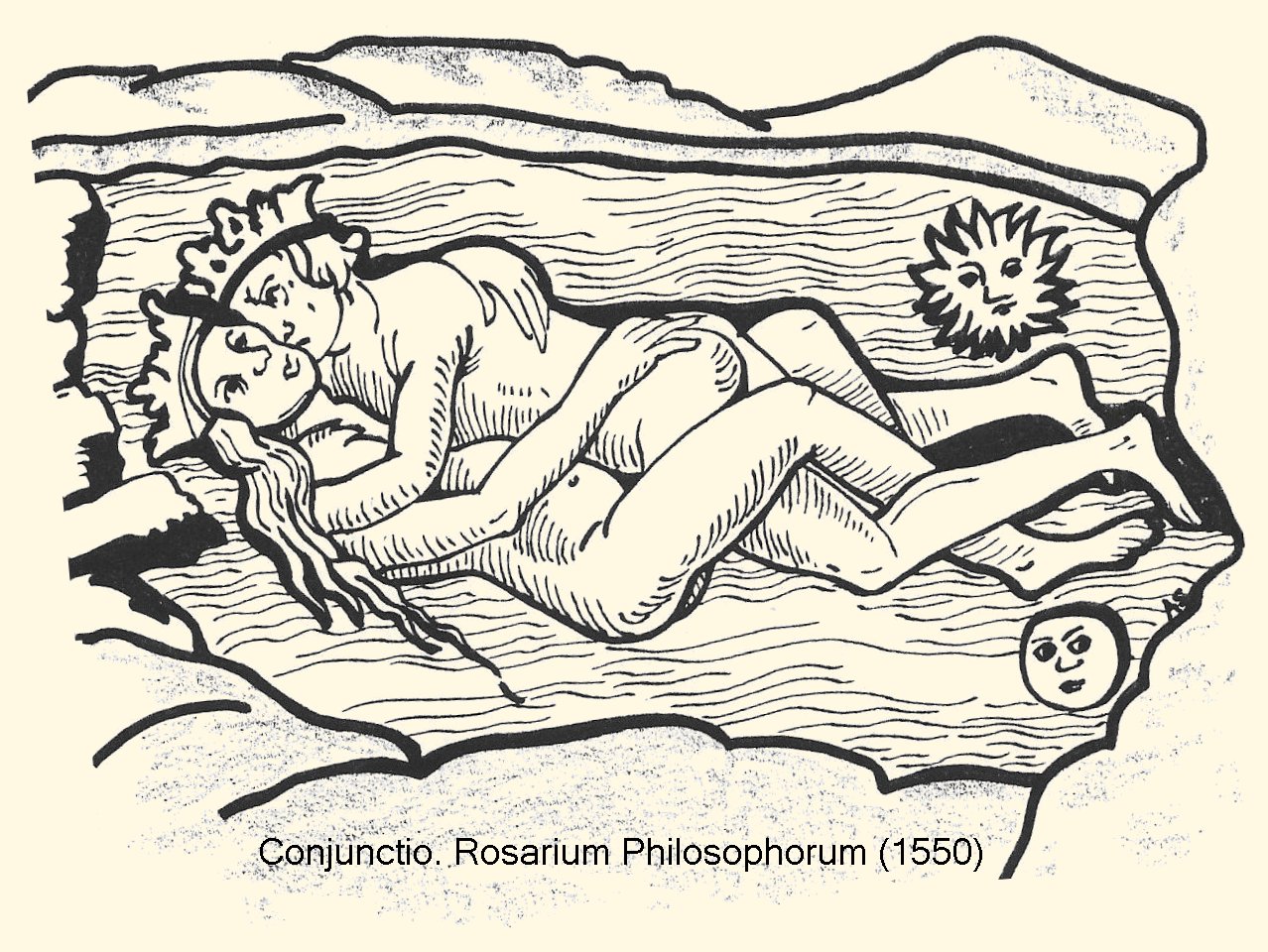

Baskin’s drawing, perhaps unexpectedly, shows not two people, nor even an androgynous being like those which commonly illustrate this stage in alchemical texts.

It is, however, unquestionably a version of the numeral, One, the symbol of unity. A passage in Jung’s discussion of the alchemical ‘Conjunction’ is enlightening here, and it seems particularly relevant to Hughes’ lines which describe the earth as “bristling and raw, tiny and lost/ … Rushing through the vast astonishment”. Writing of the Alchemist, Gerhard Dorn, Jung says:

The One and Simple is what Dorn called the unus mundus…. For him the third and highest degree of conjunction was the union of the whole man with the unus mundus. By this he meant… the potential world of the first day of creation, when nothing was yet ‘in actu’, i.e. divided into two and many, but was still one. The creation of unity by a magical procedure meant the possibility of effecting a union with the world – not with the world of multiplicity as we see it but with a potential world (MC.534).

Considering Hughes’ belief in the magical powers of poetry13, it seems very likely that this was the unity which he was attempting to achieve in this poem. By it, his protagonist, who is also Socrates and Everyman, is re–created not just in Early Egypt (which was Hughes’ stated intention) but at the very beginning of the world. So he is able to start afresh, free from pre-established constraints.

Cooper notes that the whole work of alchemy is “the spiritualisation of the body and the embodiment of the spirit”, and that “the conjuctio is the same as the mystic’s union with the One, the loss of individual identity with the limitations of the ego dissolved in the perfect whole”; but there is also a much greater purpose, and she quotes Eliade, who writes that “the aim of the opus magnum was at once the freeing of the human soul and the healing of the cosmos”14. Hughes’ poem, too, links the human world with the universe.

Jung, too, states that the goal of the Alchemist is to “spiritualise the body”(MC.535), and the absence of body in Baskin’s drawing is evident. The halo–like feathers which frame the bird’s head suggest its enlightened, spiritual nature, just as a halo is used to symbolise divine illumination in religious pictures. A halo or nimbus is also a common feature of primitive drawings of shamans and sun–gods or their human representatives, and it is regarded as symbolic of the embodiment of magical/divine powers15.

‘A Crow of Prisms’(SP)

‘Crossing the Crystal Desert’ 16

At the same time he seems to be journeying into the sun. He is being drawn through the heaven of eagles as if into the sun itself.

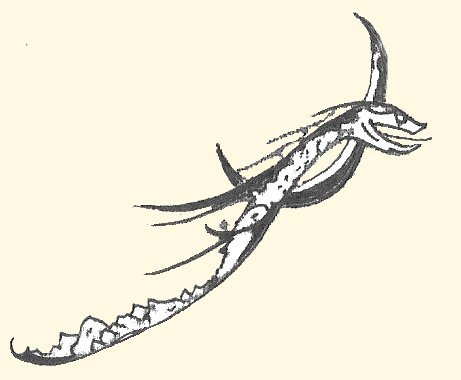

A sketch made by Hughes on one of the manuscript copies of this poem held by Exeter University shows the head and part of the body of a snake superimposed on a crescent moon:

Symbolically, the moon represents a purified soul, and the snake the latent powers of Nature17. This poem deals with exactly this combination. Humility, self–knowledge and love have brought the protagonist to a state of new–born purity. That which has survived the journey is the most precious essence, the spiritual “gem” of himself, and the paronomasia of ‘gem’ with ‘germ’ not only reiterates the “tiny”, “raw” state of the new substance which is atomic, indivisible, “beyond assay” and just at its atomic weight, but it also conveys the idea of a germ–seed with inherent strength and potential. Now, unprotected and unadorned, the ‘gem’ will be exposed to the fierce heat and light of the sun in the “crystal desert” (Baskin’s title). Whilst the natural metaphor of a new–born creature, fragile and “blood wrapped”, is carried through the poem, the imagery is also specifically alchemical for, at this stage in the process, Alchemists describe the slow emergence and growth of “a crystalline formation”18.

The desert is symbolically a place of spiritual testing and divine revelation. The pure bare ‘gem’, when exposed to the sun’s fires, may strengthen and multiply or, because it is fragile and vulnerable, it may be destroyed. Infinite care must be taken. The Alchemist, now, will take his bellows to the furnace, increasing its heat ‘breath by breath’ until the first atom of new–born substance multiplies and begins to crystallise out of the menstruum. Similarly, the protagonist must proceed with utmost caution in “the heaven of the eagles”, progressing infinitely slowly and being tested and strengthened by the sun until (to use common terms of enlightenment) his whole view of the world is altered, he sees things in a new light, and worldly affairs no longer impinge upon him.

Even at this stage in the alchemical process the cycle of ‘solve et coagula’ continues. Slowly, as the heat increases, the new crystal formation “melts into an amber-coloured liquid which gradually becomes thicker and thicker until it sinks into a black earth on the bottom of the glass”19.

Yet, the ‘gem’ survives. Like a germ of alchemical gold, or the powerful magical crystal of a shaman, it is “the repository as well as the transceiver of illumination”20 and it survives to ‘seed’ the transformation which, if conditions are right, should soon follow.

The protagonist, too, although immune to worldly affairs, is not yet completely free. He is touched by “one gravity”, which is both the attractive force of the sun which controls his movement (holding him in orbit like a “planet”) and, also, a sobering knowledge that he is “the appointed” being carrying within him the “spark” of illumination.

The fire and light of the sun pervade this poem and the mood is tentative but sure. The first two stanzas, with their clear statements of the protagonist’s situation, establish the “bare certainty, without confection” from which he begins to fly upwards: and the repetition of ‘li’ sounds between lines 11 and 15 reinforces the lifting mood. In the protagonist’s shifting perspective, Hughes conveys his growing strength and movement and the exhilaration of his flight. At the same time, he contrasts the solid and Earthly (the “mountains of torment”, “Hurrying worlds of voices”, and “traffic”) with space and light (“skylines”, “wider wings”, “simpler light”). The single line, “A one gravity keeps touching me”, creates a pause in the momentum which reinforces its sense. In the following couplets the solar metaphor encapsulates the paradox of the protagonist’s insignificance but importance, whilst the rhythms express his wonderment at his situation. Finally, the image of a spark swept by the “breath” of the sun’s “corolla” precisely captures the protagonist’s position: like a spark, he embodies some of the sun’s fire and light and thus has generative potential; and, like the corolla of petals which protects the generative parts of a flower and attracts insects to ensure fertilisation, the corolla of warmth and light around the sun will protect and nourish him, as it does all the bodies which are held within its range.

Baskin’s illustration shows a bird whose feathers are like a spiky crystalline growth. It stands solidly on its raptorial feet but there is some suggestion of streaming movement in the dark lines behind it which have left traces in the light on the right-hand side of the page. There is, however, no sign of the gem–like crystalline beauty and purity which characterises the protagonist in the poem. Nor does the picture convey any sense of the exhilaration of flight, or of the wonderful potential of the bird. This is, perhaps, the least satisfying of all Baskin’s Cave Birds illustrations in terms of its relevance to the poem.

Somehow the earthly woman has become his bride. They have just found each other, hardly created yet, on an earth not easily separable from the heaven of the eagles.

Three is an extremely powerful number in mythology, Alchemy and religion, where it is frequently associated with the relationship between gods and humans. It is, according to Dorn, “peculiar to Adam ” who is “offspring of the unarius” (the unity, One, God)(MC.367). It is often used to symbolise the time which elapses between a human being’s personal past and their re–creation as a god, or a being with god–like powers 21. The neophyte shaman ‘dies’ and ‘goes away’ for three years which seem like only three days before returning with shamanic powers22; Christ remained three days in the tomb before his resurrection; and in Alchemy, the Phoenix (whose presence is first intimated by the pure white crystalline growth) dies and “remains dead for three days, the dark of the moon”(MC.135). Confirming its solar/lunar nature, Ripley writes:

In Loosing of the bodie the water congealed shall be,

Then shall the bodie die utterlie of the flixe,

Bleeding and changing colours, as you shall see,

The third day againe to life shall arise,

And devoure birds and beasts of the widernesse,

....

In bus and nibus he shalle arise and descend,

Up to the Moone, and sith up to the Sunne23.

Now that Hughes’ protagonist has been reunited with the female half of his own nature and has become a part of Nature itself, he can leave behind his personal past and begin to make his life anew. In particular he can build a new relationship with an “earthly woman” which is based on equality. So, Hughes’ ‘bride and groom’ spend three days hidden from the world and, step by step, “with infinite care”, they “Bring each other to perfection”.

In this poem, Hughes uses both shamanic and alchemical symbolism for the re–embodiment. Eliade describes the re–creation of the shaman after mystical death, dismemberment and reduction to a skeleton, as a process in which “the skeleton is brought back to life by being given new flesh“24: this is the main metaphor of Hughes’ poem. Alchemical imagery, however, is also present throughout. Like the Alchemist and his soror mystica who make ‘Our Gold’ from base materials, this man and woman find their new forms among “rubble”, and they are “Like two gods of mud / Sprawling in the dirt”. There is a pervading mood of divine inspiration, and the couple feel “fearfulness and astonishment” and “wonderment” at the “superhuman” task which they accomplish. And, just as the alchemical gold is tested by the fierce heat of the furnace, the man and woman ensure that “They bring each other to perfection” by repeatedly

… taking each other to the sun,

they find they can easily

To test each new thing at each new step.

As Hughes’ man and woman in their “inspired” state re–assemble their bodies, the life energies re–animate them, and the whole process becomes one of joy and wonder at their own, and the other’s, beauty. It is typical of Hughes’ descriptions of Nature that each part of the body is conjured into imaginative being by a precise and beautiful detail – the “shiningly oiled” articulations of the hips; the teeth “tied” by their nerves to the spinal “centrepin” of the body; the “little circlets” on the skin of “her fingertips”; and the “steely purple silk” of the veins beneath the skin which “stitch” the body together.

There is warmth and humour, too, in Hughes’ descriptions. No sooner are the man’s hands fitted than “they go feeling all over her”. No sooner is the woman’s spine in order than she is “twisting this way and that” and laughing with delight. The “delicate cogs” of the woman’s mouth suggest her talkativeness, and the “deep–cut scrolls” at the nape of the man’s neck his sensuous muscularity. As image follows image, the beautifully precise mechanical structures of the bodies with all their ‘fittings’ and ‘parts’ become two living, moving people.

Combined with the anatomical precision, the humour and the wonder, there is sensuality. Hughes’ evocation of emotions, the joy and delight of the physical beauty of the two bodies, is linked with images which have sexual and sensuous connotations. The foot, through which man makes contact with the earth, is an ancient symbol of fertility and it is associated, also, with the sun–gods: when the woman connects the man’s feet for him “his whole body lights up”. In Tantric belief, where sexual rituals have religious significance, the cosmic life force, kundalini energy, is channelled through the body along a single pathway which is exactly replicated in Hughes’ poem as the man “connects her throat, her breasts and the pit of her stomach / With a single wire”. The woman “inlays with deep–cut scrolls the nape of his neck”, a part of the body which not only has symbolic columnar strength, but which also has great erotic power. (In Japan the nape is kept covered for this reason, and in Ancient Greece it was believed that “the pains and smouldering fire of love enter keenest deep down beneath the nape of the neck”25). Step by step, as the man and woman bring each other to completion, the pace and energy of the lines increase until, with erotic delicacy, “He sinks into place the inside of her thighs” and their delight climaxes in gasps of joy and “cries of wonderment” as they sprawl in the dirt. So, the sexual energies are subtly woven into the poem and help to bring about the god–like perfection which is realised in the final line.

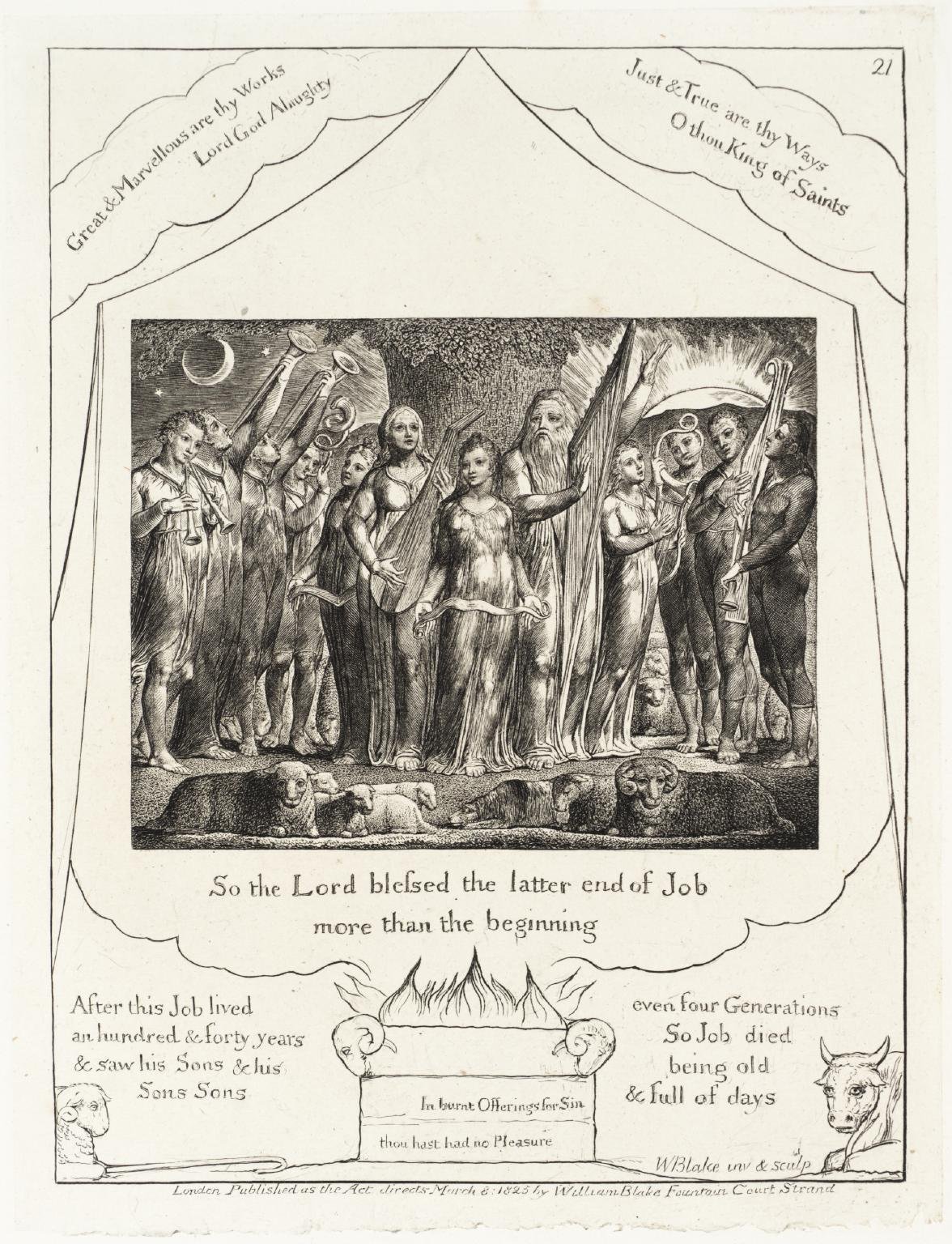

Baskin’s illustration of the half–human, half–bird, male and female has a certain naive humour about it. The couple are concerned only with each other and are given equal importance in the picture where their nakedness and their actions are quite appropriate. Sadly, however, the picture seems to lack the beauty and sensuality of the poem. This is not so in Blake’s 20th plate for the story of Job, which illustrates Job’s acceptance of the essential equality of male and female. In this etching the central figures of Job and his daughters express harmonious balance, and the surrounding texts indicate Job’s recognition of God’s universal presence. Unlike the situation in earlier plates, the women now lean against their father and are the focus of his attention, and there is sensuality and beauty in the coils of their hair and the fall of their robes26. There is sensuality, too, in the vigorous and fruitful vines, the musical instruments and the embracing angels in the frame around Blake’s picture. As in Hughes’ poem, all the energies – divine, human, and artistic – have now been combined, and the spiritual journey is almost complete.

‘The Good Angel’(SP)

‘The Angel with Good News’ 27.

The Sun Being, in its aspect of Benevolence, is an owl which is also a flower. The judgment of the Eagles, evidently, is that he should be reborn.

Directly following the climax of wonder and joy which the new and perfect human beings have achieved, there comes a “last anguish”(ED) – the “big terror” of a divine revelation. In fierce head–pounding, heart–pounding, light and heat, the flame–licked face of the owl–flower Goddess, Blodeuwedd, begins to appear. Coming like an “angel” of annunciation, she is the ‘benevolent’ embodiment of the creative powers of the sun: the Goddess: the alchemical anima mundi, “the feminine half of Mercurius”, which is the animating spirit or “the immortal soul”(MC.322).

Twice already the Goddess has appeared to the Cave Bird protagonist as an owl. In her first two manifestations she came in her aspects of death (‘The plaintiff’) and love (‘A green mother’): now, she appears in the aspect of fertility and rebirth, and her body (as in Baskin’s picture) is a “brimming heaven–blossom”, a “tightening whorl of plumes”, a feathery nest of “broody petals” from which the sun’s new creation will emerge.

Almost imperceptibly at first, a separation begins to occur, and the energy of Hughes’ lines imitates the fiery blasts which mark each progressive stage of growth. Energy is concentrated in the words, rhythm and imagery of “A drumming glare, a flickering face of flames”, until a faint “signal”, a “filament of incandescence”, becomes separated from the fires both in imagery and in line position – “As it were a hair”. Then, again, the fires become a “maelstrom”, “brimming” over and “tightening” into a “whorl of plumes”, until there emerges from the fiery “dews” of their “core” – “a mote”. Now, “A leaf of the earth / Applies to it, a cooling health” and the fires are quenched, just as the assonance of these lines cools the energy created by the alliterative ‘f’s, ‘d’s and ‘s’s which have preceded them.

The movement begins again. Spinning and twisting in the “cauldron” of heat, flushed with the “sap”, “pollen” and “nectar” of Blodeuwedd’s flower essence, the mote grows to a body which begins to stir with a life of its own. In the generative imagery of the next three couplets (lines 16–21), Hughes’ Alchemy grows towards its fruition. The corn–spirit breaks from its “mummy grain”; the ship of flowers, like a Viking funerary ship, “nudges” the hero forward towards the moment of rebirth: and the “egg–stone”, the Alchemist’s transmutative “stone that is no stone”(MC.450), bursts open28. In a crescendo of light, colour and heat, a “staggering thing”, newborn, unsteady and magnificent, emerges from the sun’s fires.

In the rebirth from fire which is the theme of this poem, Hughes links the Cave Birds story with mythological, spiritual and Alchemical themes. Many mythological parallels are apparent in the poem’s imagery, but the Alchemical (and hence spiritual) references are equally strong. First, the alchemical ‘Phoenix’ appears with “expanding feathers of white fire”29 to herald the complete transmutation. She comes, like ‘The Good Angel’ / ‘The owl flower’, in an “incandescence” of heat,and from her glittering neck feathers the healing ‘Elixir Vitae’, the ‘Philosophers’ Stone‘ will be obtained(MC.445). Following her appearance, the heat of the Alchemist’s cauldron reactivates the pure gem of crystalline gold which has lain hidden in the ashes of his mixture. Cooling ‘dews’ of pure mercury are added, “and from this conjunction it seems that a new substance is born … a Son is born”30.

As the blackness of the ashes abates, colour after colour comes and goes, rainbow colours (reminders of the mythical and shamanic rainbow bridge to the realm of the gods) which presage the appearance of the transmutative substance. At this stage, too, Alchemists report a sweet smell, “a perfume so sweet that nothing resembling it could be found on earth”31 which, like the “headful of pollen” in line 13 of the poem, is “the perfume of flowers … symbol of resurgent life”(MC.312).

With the appearance of the ‘owl flower’ the protagonist is transformed. Alchemically, in Burckhardt’s words, “The ray of Spirit acts on original nature like a magic word”32 and the embodiment of divine powers within the human is finally achieved. The alchemical ‘gold’, which is the goal of all the ‘Great Work’, has at last been made.

‘The Risen Falcon’, ‘The Liberated’, ‘A Ghostly Falcon’(ED)

He is reborn as a falcon.

Reborn, the protagonist has become a falcon, a bird of the sun. Powerful and magnificent, like the bird in Baskin’s drawing, “He stands, filling the doorway” like a successful Alchemist on the threshold of illumination. Offspring of the Eagle/Sun and the ‘owl flower’ (the “Benevolent aspect of the Sun”), and intimately linked with Man, Hughes’ “ghostly falcon”(ED) also shares many of the attributes of its avian relatives. In particular, the frequent association of falcons and men in hunting activities, where the bird links the Earth–bound human with the heavens, makes this bird an appropriate choice for a symbol of the protagonist’s acceptance by, and reunion with, the spiritual energies.

Illuminated and filled with divine power, the falcon/protagonist is released “like a convict” (ED) from his earth–bound state, and soars in exultation from the “shell”, the “mess” and the muddle of the earth and the body which have nourished him33. Free as music on the air, he escapes from the restraints of the world’s limitations, its horizons and its “clocks”, to fly to his mythological father, the source of the energies on Earth – the sun.

The power which the falcon now has is “weirdly” magical. The symbolism of the cross, and the imagery of “his shape” as “a cross eaten by light / On the Creator’s face”, signify his sacrifice and his joyous reunion with the ‘Creator’ of life on Earth: and there are connotations of divine promise for mankind in his resurrection and his resorption into the cosmic source.

As he “shifts” between Heaven and Earth, his cross–shaped shadow brings flames and torment to the dark “thickets” of the world. Even at a distance his disturbing power is felt (just as sunspots can cause earthquakes), and “Where he alights”(the phrase is deliberately ambiguous) the world is radically and apocalyptically altered. Yet, the change is both creative and destructive: like the sloughing of a skin, the “leafless apocalypse” precedes maturity and contains the promise of a new beginning – a chance to achieve, as the protagonist now has, a “burning unconsumed” state of illumination.

In the penultimate couplet of the poem, Hughes draws together all the threads of his poetic epic in a magnificent image which expresses all his own love of Nature and the tenderness, the power, the hope and the beauty which he sees in it. The “wind–fondled crucible of his splendour”” is at once the falcon’s own body, the Earth and the Alchemist’s vessel, within which the transformation has been made. The creation which has emerged – the falcon, the “liberated” spiritual gold – brings the words of the Hermetic Emerald Tablet to fruition:

3. Its father is the sun, its mother the moon, the wind carries it in its belly, its nurse is the earth.

….

7. It rises from earth to heaven and comes down again from heaven to earth, and thus acquires the power of the realities above and the realities below. In this way you will acquire the glory of the whole world, and all darkness will leave you.34.

This is the climax of the Cave Birds protagonist’s journey, as it is the supreme moment of Hughes’ poetic alchemy.

The falcon represents the achievement of cosmic unity; the resolution of chaos which the Greek philosophers and the Alchemists sought.

Hughes’ protagonist, a creature of Nature but one which began this journey alienated and divided from Nature and from his own natural energies, is now reunited with both. The transmutation is complete and, now, “The dirt becomes God”, divinely illuminated, immutable; the ‘immortal Adam’ has been re–created as the ‘diamond body’ – ‘Our Gold’: and the cycle of division and reunion has come full circle35.

In the words of Basil Valentinus:

the last Matter may be changed into the first, and the first into the last [by] that Spirit penetrating all things, which presides or bears rule in all things, yet is involved and absconded matter and defilements on every side; from which if once freed, it returns to the purity of its own substance, in which it produceth all things, and is all in all36.

The same completion can be seen in Blake’s final picture of Job (Plate 21). This illustration closely resembles the first illustration in Blake’s sequence, but all evidence of discord and division has gone from it and it is vibrant with life and light, music and harmony. Only one detail of the picture sounds a note of caution, and that is the presence amongst Job’s sheep of a sleeping dog, an animal which is “emblematic of accusation throughout the Bible” and which is interpreted, here, as a sign that the cycle is complete but unfinished37.

Hughes’ sequence of poems, too, is unfinished. The alchemical ‘gold’, whether spiritual or mineral, is only of value for its ability to transmute other substances to its own pure form, and for this purpose it must be recombined with ‘Base Matter’. So, the “ghostly falcon” must return to Earth in obedience to the Hermetic instruction:

Eighthly – Ascend with the greatest sagacity from the earth to heaven and then again descend to the earth, and unite together the powers of things superior and things inferior. Thus you will obtain the glory of the whole world, and obscurity will fly away from you38.

Like a falconer releasing his falcon, the Alchemist who gives the spirit its freedom cannot restrain it, he can only wait and hope for it to return to him with its divine, creative, powers. As in Nature, which is the worldly manifestation of divine unity on which Alchemy is based, the flux of energy and matter is constant, and rebirth is but the prelude to a new cycle of death, decay and resurrection. The Goddess, in her triple aspects of Mother, Wife and Layer–out, must repeatedly be satisfied: the alchemical synthesis must be constantly repeated. The ‘Great Work’ is never finished.

In Ripley’s words, the twelve ‘gates’ to the Castle (known in Arabic alchemy as the ‘Treasure–House of Wisdom‘) have now all been opened, but the alchemist still has work to do:

Now hast thou conquered these gates twelve,

And all the Castle thou holdest at they will.

Keepe thy secrets in store to thy selfe,

And the commandments of God looke thou fufill,

In fire see thou continue thy glasses still,

And multiply thy medicines aye more and more…39.

In Cave Birds, Hughes’ alchemical rituals have brought energy and unity to a chaos of themes, ideas and images, but the alchemical ‘gold’ of pure imaginative energy which he has distilled from this ‘Base Matter’ must be used in new creative endeavours if it is to be of lasting value. One poem, or even one poetic sequence, cannot heal the divisions in our world, and Hughes’ comment to Faas, part of which appears as the ‘Finale’ of the Cave Birds sequence, makes just this point:

One poem never gets the whole account right. There is always something missed.40

At the end of the ritual

........................up comes a goblin (CB.62)

And Baskin’s goblin, which rises from the final page of the work, is a suitably ambiguous figure resembling a tiny eagle–owl – Hughes’ own poetic symbol of the Goddess.

For permission to quote any part of this document contact Dr Ann Skea at ann@skea.com

Go To Next ChapterReturn to Poetic Quest Homepage

Go to Ted Hughes Homepage for more options