Calcination, Mortification, Putrefaction, Nigredo

The immortal soul is the invisible celestial fire1.

The alchemical synthesis begins with ‘Base Matter’ or ‘Raw Stuff’, which is a mixture of substances, a chaos in which the prima materia (the pure original matter and energy of the Source) lies concealed. This ‘Base Matter’ is the ‘lead’ (the densest and basest of metals) from which the alchemical ‘gold’ will be made. It comes under the astrological sign of Saturn (♄) and, for the Alchemist, its spiritual parallel is “the chaotic immersion of consciousness in the body”2. Saturn, according to Burckhardt, represents the human intellect in its capacity for knowledge, as opposed to its capacity for understanding.

In Cave Birds, the first stage of the alchemical synthesis extends from ‘The scream’ to ‘The executioner’, and the ‘Base Matter’ with which the synthesis begins is the protagonist. His “Flesh of bronze, stirred with a bronze thirst” (CB.7), and his “bronze image” (CB.8), signify some small progress from the original chaotic state of the human organism, for bronze is a lead/copper mixture which symbolically combines Saturn and Venus, Intellect and Spirit. The protagonist, therefore, has knowledge but not understanding.

He sees the beauties and horrors around him but, because of his rational abilities, he feels himself to be superior to the forces of Nature which govern these things. It is this arrogance and pride which will be his downfall. Hidden within him, however, is an element of Spirit through which the long journey towards understanding may begin. This is the divine element in human nature, the prima materia through which spiritual transmutation may be achieved.

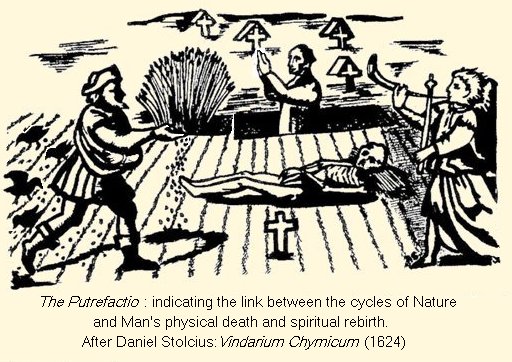

The first procedure undertaken by the Alchemist is one of gentle heating: Calcination. During this heating, the first separation of Mercury from Sulphur occurs3. Next, the elements are re–combined so that, by the destructive power of Mercury, the matter is gradually broken down and brought into solution. Metaphorically, this is ‘The First Death’, the first cleansing of the ‘Base Matter’ during which it undergoes ‘Mortification and Putrefaction’. This first stage ends in a return to chaos which is symbolised by a blackness that Alchemists call the nigredo or the ‘Raven’s Head’.

Spiritually, the first alchemical stage is paralleled by an awakening of awareness or consciousness in the ‘Base Matter’ of the human being. It corresponds to the first examination of the inner world and it is often accompanied by the first stirrings of conscience. In Hughes’ own life, one might regard his early apprehension of the intrinsic value of animal life as just such an initial awakening. For his Cave Birds protagonist, however, the situation is more complex and traumatic.

The ‘Spirit’ which erupts from within the protagonist to begin the work of transmutation is unrecognised and resisted by him but, through the persistent ‘heat’ of its accusations, his self–consciousness begins. By this means, the ‘Base Matter’ of the protagonist is gradually broken down, he is ‘mortified’ and, as he begins to lose his insensitive and arrogant facade, he enters a state of confusion and blackness. This state, which corresponds to the nigredo, is represented in the poetic sequence by ‘The executioner’ – a raven, like the bird in Baskin’s powerful drawing which accompanies this poem.

In psychological terms, Jung likens the first stage of the alchemical work “to the encounter with the shadow” (MC.497) which represents a psychic split. The emphasis on light and shadow, dream and reality in ‘The scream’ and ‘The summoner’ may certainly suggest such an encounter, but the shadow also has mythical and folkloric associations with the Underworld and with the Soul, both of which are of great importance in Hughes’ cave drama. The summoner, therefore, is equally an eruption from the suppressed sub–conscious energies of the protagonist and an appearance of Hermes/Mercury, the summoner and psychopomp who traditionally guides the Soul on the journey to the Underworld.

Mercury, the summoner, the alchemical divine spirit in ‘Base Matter’, appears in the early Cave Birds poems in several different emanations all of which prod, probe, pull apart and devour the material aspect of the protagonist. The solution in which this destruction takes place known to Alchemists as ‘the menstruum’ which devours the lifeblood containing the seed of re–birth: Mercury is the menstruum4, it is also “the water which teareth the Bodies, and makes them no Bodies”5. So, in Cave Birds it appears as the “blood-eating” summoner (CB.8), and as the vulture, “the blood-louse / of ether”(CB.12), the agent of bodily destruction.

Alchemically, such destruction is necessary, for “Unless the bodies lose their corporeal nature and become spirit, we shall make no progress in our work. The solution of the body takes place through the operation of the spirit…”6.

Following the first separation of Spirit from Matter, Mercury, in the first gentle heat of the alchemical process, begins the destructive tasks of mortification and putrefaction through which the Sulphurous impurities of the ‘Base Matter’ are released.

Heat, at each stage of the alchemical process, is carefully controlled and four degrees of fire govern the four stages of the alchemical process. At this stage “the first degree so gentle be that feeling may excel it [i.e. heat which may be handled… By this degree of fire and not by any other, our matter ought necessarily to be purified, dissolved, mortified and made black”7.

So, although the first encounters which the Cave Birds protagonist has with the bird–beings promote cold terror which “chills” him like “ether”(CB.12), and the mood of these first poems is rational and cool, there is warmth enough in the accusations to promote the flush and sweat of embarrassment and to begin the processes of guilt and mortification.

Following the mortification, or stripping down, comes the putrefaction which returns the body to a solution or a state of chaos. In Alchemy, this stage is known as ‘the return to the mother’ because it is the necessary preparation for the re–birth of the spirit in its first state of purification.

In Cave Birds, a change in the nature of the interrogating vulture signals the change from mortification to putrefaction in the alchemical process. From being a bird of destruction in ‘The interrogator’, she becomes a comforting angel in ‘She seemed so considerate’:

‘Wings’, I thought, ‘Is this an angel’? (ED).

Symbolically, this second ‘vulture poem’ presents the protagonist’s return to the mother and the necessary surrender of will which spiritual teachings regard as part of the return to the womb prior to rebirth.

Such symbolism has Natural parallels, and underlying the symbols which Alchemists use to describe the process of putrefaction are the fertility cycles of Nature, for, as the Alchemist, George Ripley, wrote:

... without the graine of wheate

Dye in the ground, encrease maist thou none get.

And in likewise without the matter putrifie,

It may in no wise truly be alterate 8.

In Alchemy, therefore, it is an established principle that without putrefaction “no seed may multiply”9 and that there can be “no generation without corruption”10.

Just as Hughes’ vulture is a black agent of the sun, so the darkness of putrefaction is often represented in alchemical texts by a black sun (Sol niger). In practical Alchemy, the whole process involves a slow, progressive darkening of the substance, which is kept in a sealed vessel (the Philosophers’ Egg) at a constant gentle heat. Eventually, “a black colour and a fetid smell” indicate that the “deadly poison” of the “Raven’s Head”11 has been obtained and the first stage of the work is complete.

Within the Philosopher’s Egg, the separated Sulphur and Mercury of the body are recombined and dissolved in a liquid nigredo. The Cave Birds poems, ‘The plaintiff’ and ‘In these fading moments…’, present again two aspects of the protagonist which are, respectively, a dry, burning, Sulphurous aspect and a cool, Mercurial aspect. Each has already been purged of some imperfections. The Sulphur which remains now is the inner Sulphur, the Soul. But the Mercury is, as yet, impure, for although the mask of arrogance has been destroyed, the protagonist still attempts to exonerate himself by a cool, rational plea of “imbecile” innocence (CB.20).

At the end of ‘In these fading moments…’, as Nature’s world darkens with the snow–melt and the muddy, swirling rivers of a pre–generative chaos akin to putrefaction, she rejects the protagonist’s plea. He is condemned to the poison of the Raven of Ravens (“his hemlock”(CB. 22)) which engulfs him in the total blackness of the pre–birth world, and the return to the mother is completed.

* * * * * * * *

‘I was just walking along’ (ED)

The (protagonist) hero, in the decent piety of his innocence, is surprised. What has he failed to take account of ?12

In ‘The scream’ Hughes suggests the blind incomprehension and self-deception – the unenlightened chaos – of his protagonist in terms which reflect common human attitudes. The situation he describes is the status quo from which the journey, the transmutation, must begin.

The protagonist, who later describes himself as an “imbecile innocent” (‘In these fading moments I wanted to say’(CB.20)), is less innocent than he ‘piously’ believes13. He is one who lives in naive non–comprehension of his own nature: A “newborn babe” whose “Flesh of bronze” and “bronze thirst” link him with the degenerate mythological ‘race of bronze’ which, according to Ovid , was “more fierce and warlike, yet unstained by crime” than the first people made by the gods in the Golden Age14. Like us, he has fallen from his original state of innocence into the chaos of experience, and his bronze thirst inures him to violence and predisposes him to complacency and pride. He is child-like in his naivety but, as in Blake’s ‘Jerusalem’,

The Infant Joy is beautiful, but its anatomy

Horrible ghast & deadly: Nought shalt thou find in it

But dark despair & everlasting brooding melancholy: (Jer.22:22–4).

The protagonist’s world, too, is the Blakean world of experience in which Man’s divided nature and his destructive presence are ubiquitous. It is our world: a world desensitised to Nature – a world in which life is crushed by the “inane weights of iron” which are Man’s mechanical inventions. Its ills are symbolised by images of mutilated creatures: people and rabbits are crushed, “Calves heads all dew-bristled with blood” grin from counters, and the images and atmosphere suggest a threatening undercurrent of Dionysian energies which periodically erupt in bloody rituals of slaughter such as Hughes depicts in Gaudete.

Amidst all this, however, the protagonist feels no sense of his own mortality and no responsibility for the deaths of other creatures. His is a mind “desensitised to the true nature of nature”15 and, for him, the world is as it always has been. His “childhood’s / Nursery picture”, “the sun on the wall”, is still there, co–existent with “my gravestone”, with which he “happily” shares his dreams16. He feels himself to be in a position of invulnerability. His self–delusion, like a “falsifying dream” of the Hawk in ‘Hawk Roosting’(THCP.68), allows him to feel “creaturely” bravery in the face of mechanical threats and to view destruction with equanimity from a detached, superior position on “the wheel of the galaxy”. Yet, it is this alienation from Nature, this lack of understanding of his own place in the Natural world, which is the very substance of his guilt. Like Socrates, the arch rationalist with whom Hughes identifies him, he will later defend such beliefs with rational argument. Now, however, the enduring and powerful forces of Nature (exemplified in the poem by the hawk, the mountains, the worms and the newborn baby) make their inevitable intrusion into his life and demand his submission.

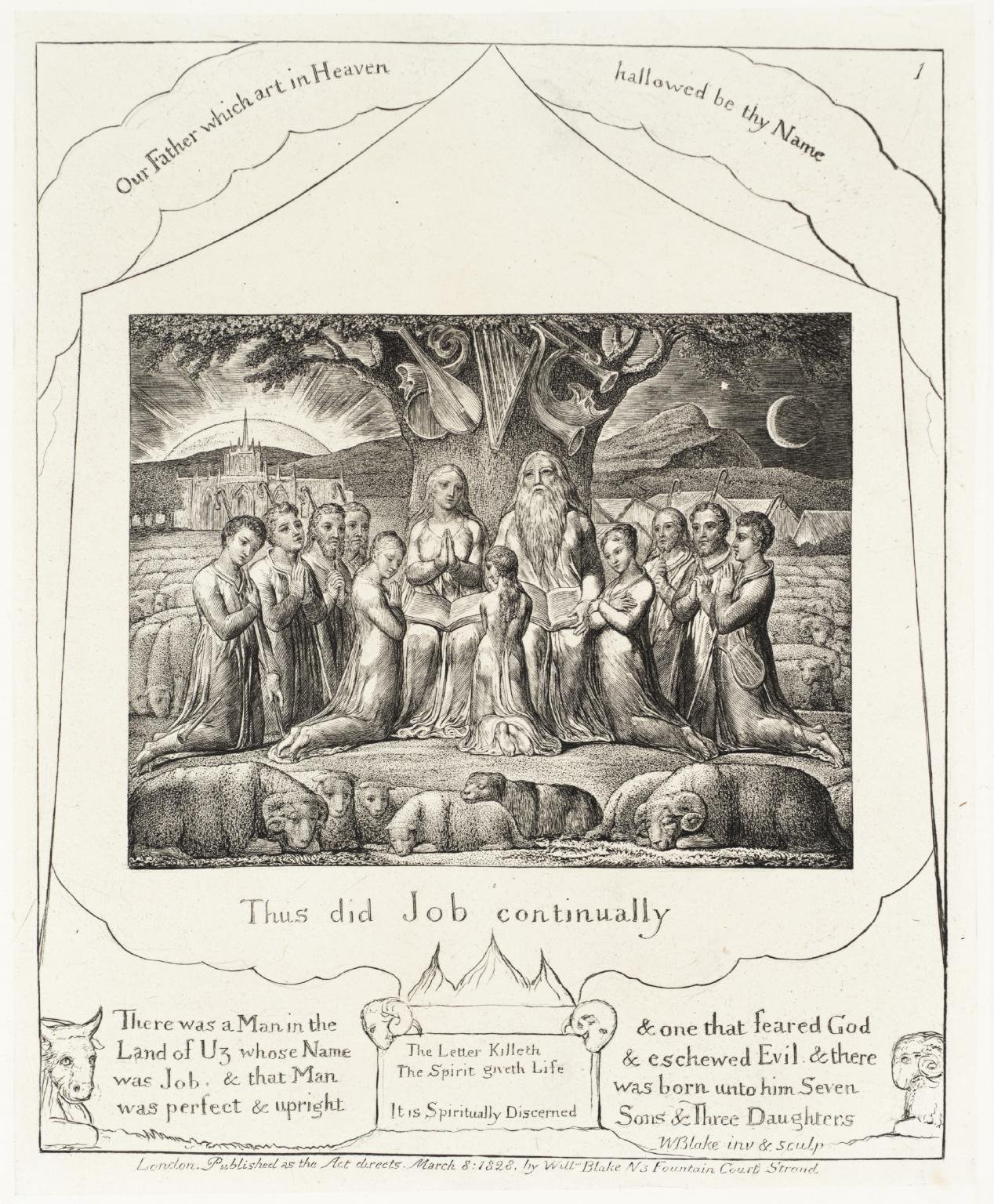

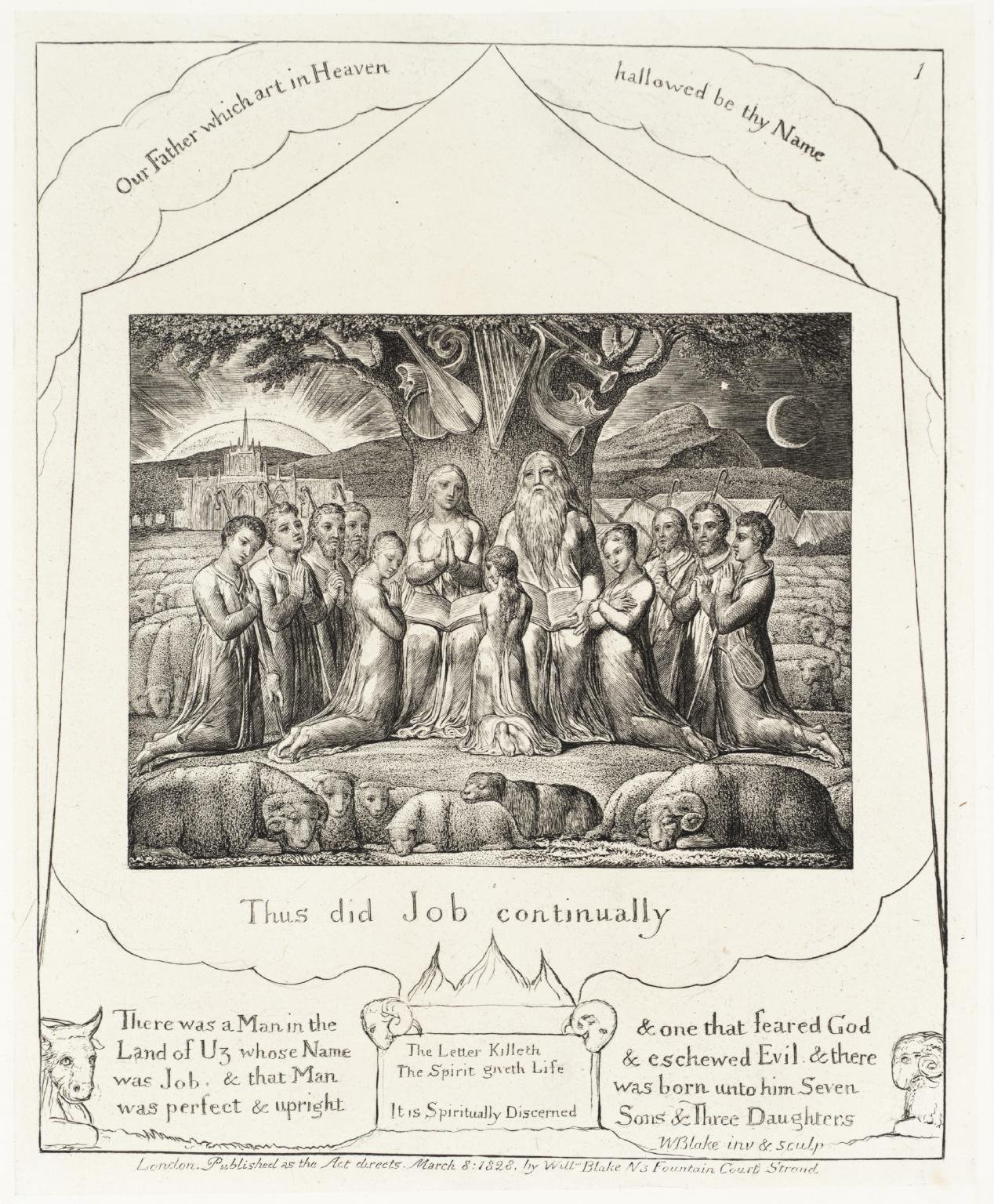

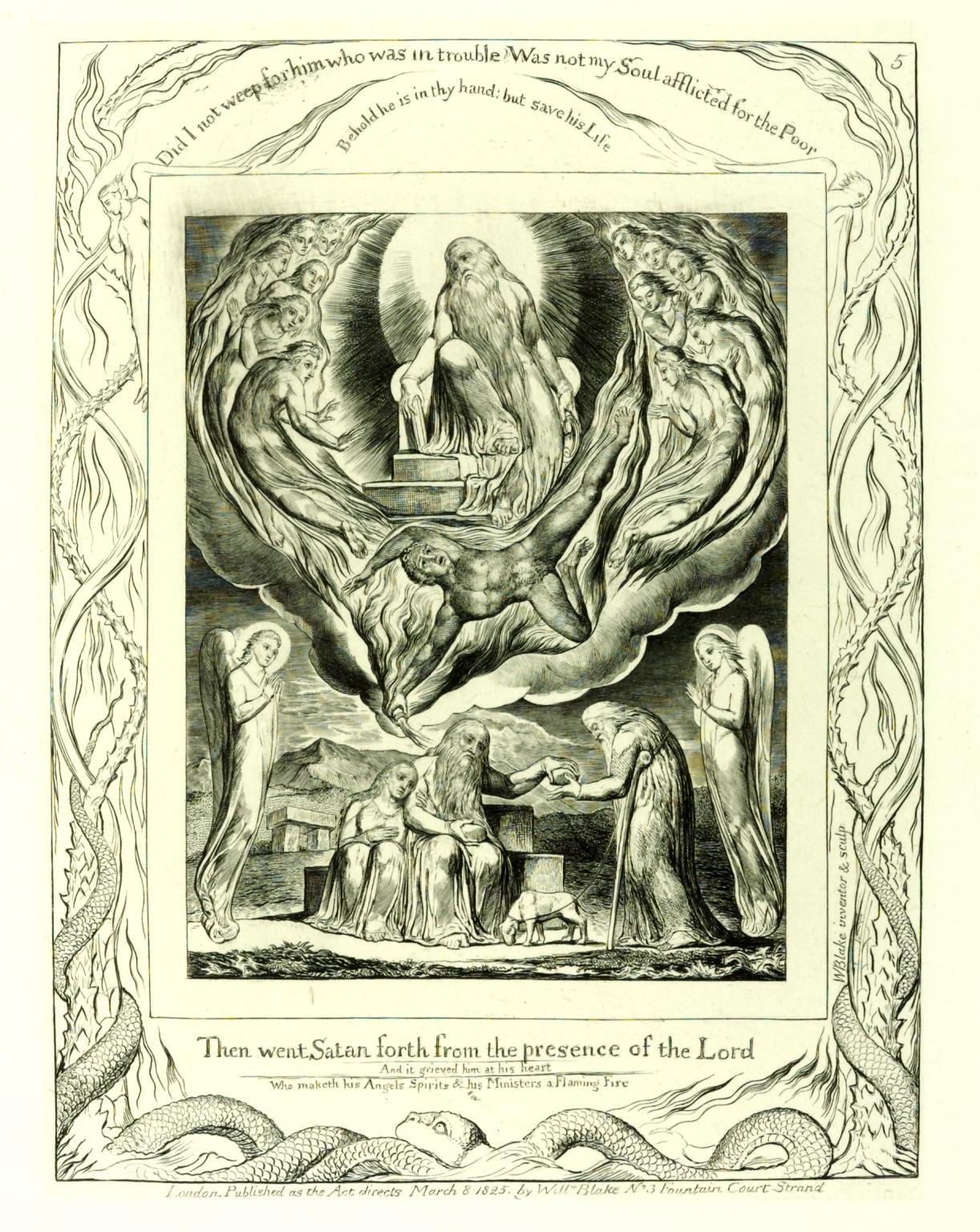

The unexpected, seemingly inexplicable, and horrifying events which occur in the life of the Cave Birds protagonist resemble, in many respects, those which are described in the biblical account of the life of Job. Job, too, is pious, and the misfortunes and trials to which God subjects him are seemingly unwarranted. Yet, as Blake makes clear in the illustrations in which he interpreted Job’s story, Job, like Hughes’ protagonist, is guilty of complacency, pride and self–deception which distort his vision and deny him true knowledge of spiritual unity17.

Blake’s first picture of Job (Plate I, below) includes the biblical text which describes him as “perfect and upright”. Symbolically, however, Blake shows Job as a victim of ‘single vision’, cut off from imagination and feeling (the instruments which symbolise imagination hang unused in the tree). Similarly, in the first poem of the Cave Birds sequence, Hughes’ protagonist displays a superficial serenity which is undermined by certain other aspects of the overall description of him. As events proceed, the recognisable pattern of a journey of spiritual enlightenment becomes apparent in both stories, and the similarities of theme and treatment continue, but there are yet other details in Hughes’ handling of the Cave Birds story which make the connection between his ideas and those of Blake more certain

The foolish pride and brazen arrogance of Hughes’ protagonist are beautifully captured in the Baskin drawing for a later poem in the sequence, ‘The accused’(CB.24), which was earlier entitled, ‘Socrates’ Cock’(ED). At the same time, this picture of “A Tumbled Socratic Cock”18 connects the protagonist with mythological epic heroes such as Hercules, who is shown in the Durer etching, ‘Der Hercules’, “as wearing a cock’s comb or head of a rooster, on his head”19. Less well known, but more pertinent to this discussion, is Blake’s etching of his character, Hand, who is shown at the beginning of Chapter 4 of ‘Jerusalem’ (Jer. Pl.78) with a “ ‘ravening’ beak… and a cock’s comb”20. Hand, the eldest of the twelve Sons of Albion, is the “Reasoning Spectre”. He is described by Foster Damon as the source of “the whole materialistic system of war and of society” and as the destroyer “of all innocent joys [who] opposes love with cruelty”21. Hughes’ familiarity with this particular etching is most likely, since it occurs in Blake’s work immediately opposite a passage on which Hughes has based at least two poems, ‘Ballad from a Fairy Tale’(THCP.171) and ‘The Angel’(THCP.492):

among my valleys of the south

And saw a flame of fire, even as a Wheel

Of fire surrounding all the heavens: it went

From west to east against the current of

Creation, and devour’d all things in its loud

Fury & thundering course round heaven & earth.

By it the Sun was roll’d into an orb:

By it the Moon faded into a globe,

Travelling thro’ the night; for, from its dire

And restless fury, Man himself shrunk up

Into a little root a fathom long.

And I asked a Watcher & a Holy–One

Its Name; he answer’d: “It is the Wheel of Religion”. (Jer. Pl.77. 1–13).

Not only is Blake’s figure, Hand, suitably related in character to Hughes’ protagonist but he occurs in Blake’s work immediately after the passage, “To the Christians” (Jer. Pl.77). This outcry against the divisive form of Christianity which emphasises “Mental Studies and Performances” and despises “Art and Science”, is one which is echoed in Hughes’ own writings, especially in the Introduction and Note to A Choice of Shakespeare’s Verse, where he decries the Calvinist influence which taught us to “divide nature, and especially love, the creative force of nature, into abstract good and physical evil”22.

One further point can be made concerning the relationship between Hand and the Cave Birds protagonist. The positioning of this particular etching of Hand in Blake’s poetic sequence, following, as it does, Blake’s vision of some fiery and violent change, makes it apparent that Hand, like Hughes’ protagonist, is about to experience such a change. Erdman, in fact, takes the cock’s comb on Hand’s head as “a symbol of morning” which metaphorically suggests that “the night of death ‘is far spent, the day is at hand’”23. The nature of the change, both for Hand and for Hughes’ protagonist, is to be revolutionary, and Blake’s vision of the clash of “this terrible devouring sword / … opposing Nature!” (Jer. Pl.77: 15–20) is also expressed in occult and fiery terms reminiscent of the imagery used by alchemists to describe allegorical dreams and visions.

Hughes’ protagonist, in his divided state, also opposes Nature. But his appetites, like those of “a newborn baby at the breast”, are still controlled by Nature. When he attempts to praise the world he becomes aware of a radical split within himself. One part of him, represented as “his mate” (who has, significantly, had some part of himself removed), in his half–coma, half understanding, manages a rigid “stone temple smile” and a raised hand – a mindless ritual of praise which appears in early drafts of the poem as:

He merely let his thoughts float away

Into the starry silence

Into the book of Job

Into the burial service

Into the yawn

That suddenly yelled …

and:

I merely prayed, automatically:

‘Blessed be the name of …’ (ED).

Within him, however, there has crystallised a hard. painful, fundamental truth which, like “A silent lump of volcanic glass”, tears his “gullet” and vomits itself forth in a scream. So, with a suggestion of ritual sacrifice conveyed in the image of “an obsidian dagger”, Hughes begins the breaking down of self–image which must precede any spiritual transformation. And, with this first indication of the horror which exists beneath the pious facade of the protagonist, the stage is set for ‘The summoner’ to appear.

‘A Hercules-in-the-Underworld Bird’24

The hero’s (protagonist’s)25 cockerel innocence, it turns out, somehow becomes his guilt – His own nature, finally, (the inescapable creature of his flesh and blood) brings him to court.

The summoner is essentially a part of the protagonist. He is the spectre from the subconscious mind, the daemon, the possessor of deep instinctive truths who has the potential to both destroy and save the protagonist.

He is analogous to ‘Lucifer’, the light bearer, who appears in Plate 5 of Blake’s Illustration of the Book of Job under his other name, ‘Satan’, ‘The Angel of the Divine Presence’. Satan/Lucifer, who is Job’s summoner, is often, like Mercury, identified with the dragon of Chaos.

Satan/Lucifer is the first of Blake’s ‘Seven Eyes of God’, seven states which Blake formulated to describe “the path of Experience which Job must tread” on his spiritual journey. In Blake’s title page for his Illustrations of the Book of Job, these seven states are depicted as angels symbolically grouped to show the descent from the material state and re–ascent into the spiritual state. According to Foster Damon, Blake believed that

These seven States were divinely instituted so that man should mechanically be brought back to communion with God. In the epics, Blake’s technical names for the Seven are Lucifer, Molech, Elohim, Shaddai, Pahad, Jehovah and Jesus. They represent Pride of Selfhood; the executioner; the judge; the Accuser; Horror at the results; Perception of Evil; and finally the Revelation of the Good. This is Man’s customary course through Experience 26.

It is readily apparent that the titles of some of the Cave Birds poems are identical with certain of Blake’s seven States, and the connection between the ‘cockerel innocence’ of Hughes’ protagonist and ‘Lucifer’ as ‘Pride of Selfhood’ is easily made through their shared blind arrogance. This connection is reinforced by Foster Damon’s explanation that Blake

found Job’s tragic flaw in [his] innocence. Supported by his material prosperity, he has never grown up spiritually, has never trod the path of Experience… Satan the Accuser dwells in his own brain. And this Satan is to usurp for a time the place of the true God 27.

As with Job’s Satan, the summoner of Hughes’ protagonist dwells within him. At night, when the conscious mind is at rest, this other self is a “Shadow stark on the wall”, “Spectral, gigantified”, accusatory. Just occasionally, like a glow of light, “an effulgence” in a leafy oakwood28, it can be “glimpsed” in a more benign form. It is “your soul”, “your protector”, hidden deep beneath the mask of arrogance which is the “grotesque” brazen facade of the day–time self.

The only ‘evidence’of the other’s existence is “A sigh” (traditionally believed to be an exhalation of the Soul), or some half–remembered promptings which remain in the mind like left–over “rinds and empties”. But, “sooner or later”, this primitive, “blood–eating” self, which grows parasitically within, must be recognised and acknowledged as a part of the whole identity. The importance of this lesson and its relevance for all Mankind are indicated in Hughes’ shift from first person narrative in ‘The scream’ to the use of an inclusive ‘you’ in ‘The summoner’.

Although the summoner is your protector and your Soul, and although the soft, pleasing sounds and imagery of line 7 of the poem (“Among crinkling of oak-leaves – an effulgence”) suggest his healing association with light, this figure from the subconscious is terrifying. He is an apocalyptic symbol of death, and in four cold, clipped lines Hughes captures the Mercurial paradox of protection and destruction which he embodies, describing him as:

The carapace

Of foreclosure

The cuticle

Of final arrest

Baskin’s illustration shows a wingless bird with human genitals. It suitably portrays the dual nature of the Summoner, combining suggestions of the soft feathered body of a later illustration for ‘A green mother’(CB.41) with a crow’s head and the vicious looking leg spurs and claws of a raptor. Here, truly, we see “the grip” which cannot be avoided.

‘A Desert Bittern’ / ‘A Deep–wading Desert Bittern’(ED)

‘A Deep Wading Desert Bittern’29

He is given some indication (The council for the opposition gives him some indication (ED)) of the nature of the charge. What is he guilty of exactly? Being alive? Or of some error in the use of his life.

In the Exeter drafts there are three quite different poems under this title. The one included in the A sequence was the version read at the Ilkley Festival and in the BBC broadcast of Cave Birds. Keith Sagar collected the broadcast version in The Achievement of Ted Hughes(p.346). None of the versions were included in the published sequences.

All three poems indicate that the protagonist’s guilt does not lie simply in “being alive” but in the insensitive materialism in which he has indulged at the expense of the suppressed inner self30.

The Advocate comes to redress the balance, listing the protagonist’s sins and “Totting the count” (all versions):

Voice C: You corrupted the pure light

To put it to work.

…

Voice B: Not only did you borrow … you stole.

C: You plundered … with stretched mouth glistening.

A: You amassed, you wallowed in engrossment

B: With a bonfire unconcern for the screaming

In the cells (Version A).

All this continued until the inner self was a

… speechless upside–down corpse

Hanging at your back

Who has paid in kind (Version C).

The upside–down corpse is a common symbol in occult and mythological ritual. Odin, the Nordic sun–god, and the Greek Dionysus, were annually sacrificed in this position prior to their descent to the Underworld and their subsequent re–birth31. Like ‘The Hanged Man’ in the Tarot pack, the symbolism is of the overturning of the material world by the natural, emotional world; it is the symbolism of imminent revolution and change. In the poem, the Advocate (who has been the suspended inner energies of the protagonist) comes to begin the awakening and the revelation of the painful truth. He is, in one version, “like the piper/opening the mountain of oblivion”. In others, he describes himself as

… the hypodermic. My first word

Will start the truth shining from your pores (Versions A, C).

Here I sit on your brow, like a mosquito

Totting the count (All versions).

So, like the “blood–louse” vulture, the mosquito–like Advocate will extract a blood–sacrifice from the protagonist in expiation of his guilt.

And, just as in the Alchemist’s fire “the body becomes moist and gives forth a kind of bloody sweat” (MC.40), so the first pricking of conscience produces the sweat of guilt and the disintegration of the bronze image begins.

He is confronted in court with his victim. It is his own daemon, whom he sees now for the first time. (The protagonist realises he is out of his depth) He protests, as an honourable Platonist, thereby re–enacting his crime in front of the judges. He still cannot understand his guilt. He cannot understand the (decisive) sequence of cause and effect.

In order to undertake the journey to the Underworld, the human body must be transformed. The shamans of primitive groups achieve this by adopting the form of an animal: ordinary humans usually achieve it through death. In this poem, Hughes uses images of ritual death and transformation which are common in both mythological lore and spiritual doctrine. His protagonist, however, is being torn apart by an inner conflict.

As the revolution of the elements of personality continues, the suppressed natural energies are no longer under the control of the protagonist’s rational powers. He may argue his “’way out of every thought anybody could think”, but he is unable to control his body and his emotions, or “the stopping and starting / Catherine wheel” in his belly “which seemed to have been nailed there to enlighten him”(ED).

The symbols of revolution are central to this poem. The fiery wheel of the sun and of Nature, like the wheel of torture on which St. Catherine was martyred, is turning and burning, and no rational ability in any creature can stop it.

Seeking to evade his guilt, the protagonist exacerbates the situation by denying his feelings and offering, as an ‘honourable Platonist’, rational, abstract arguments of explanation. Inevitably, each of his explanations for the status quo becomes a further mutilation of his daemon and hence of himself. In an exact representation of the Advocate’s accusation that the rational self has fed on the hidden daemon, ‘Civilisation’ and ‘Sanity’ (those excuses which are fundamental to our own rationale for our way of life) are vividly and graphically shown as causing the protagonist’s mutilation and death:

When I said: ‘Civilisation’,

He began to chop off his fingers and mourn.

When I said: ‘Sanity and again Sanity and above all Sanity,’

He dismembered himself with a cross–shaped cut.

In earlier drafts of the poem, the protagonist, like Blake’s Job, relies on the books of Law, saying:

Seek Truth, forsaking all other.

Honour thy father and mother.

Rule of Law and protection of the weak (ED)

These are the rigid, unchanging “Laws of peace, of love, of unity /of pity. compassion, forgiveness.” (U. II:41–2) which Blake’s Urizen inscribed in “The Book /of eternal brass”(U. II:41–2); they are the rigid moral codes which Blake sees as distorting Mankind’s instinctive acceptance of true Christian love and forgiveness. Hughes shows the symbolic emptiness of these proffered excuses by his use of capital letters, thereby suggesting the protagonist’s belief that just the mention of such powerful words can justify everything.

The protagonist’s attempt at dialectic fails and he is forced to share in the ritual sacrifice which is made. This, by its nature (disembowelment with a cross–shaped cut) resembles the annual sacrifice of the Sun–king to the Goddess, which was once practised to ensure the continuance of the natural cycles of fertility.

Baskin’s illustration, too, emphasises the symbolic nature of the sacrifice, showing the dismembered bird in a position which suggests crucifixion and which combines the ‘Y’ shape of the tree of life symbol (inverted to indicate death) with the ‘T’ of the Tau cross of generative power and change32.

So, the poem ends with the physical death which must precede a journey to the underworld:

When they covered his face I went cold.

Yet, there is every indication that this is but a prelude to re–birth as the powerful natural forces take their course.

‘A Titled Vulturess’ 33

The crime, which seems to be a form of murder, brings into question the death-penalty. The Interrogator for crimes involving death collects the evidence from the accused.

Like Grdhramukha, the corpse–eating, vulture–headed deity from the bardo, the interrogator now confronts the protagonist. She is the sun’s agent, with the power and cruelty of the sun; “the sun’s keyhole”, through which it “spies” into the dark and barren “badlands” of the material world. Her ‘titled’ status links her with the gods, particularly with the vulture–headed goddess, Hathor, of The Egyptian Book of the Dead, who was the succouring Celestial Cow–goddess, wife/mother of the hawk–headed Sun God, Horus, and who was later identified by the Greeks with Astarte 34. Hughes’ vulturess is also connected with the vulture sent by Zeus to torment Prometheus.

Through the interrogator, the body is ransacked: “ the camouflage of hunger”, which is both the physical body (concealing the stomach and intestines) and the mask of the personality (which hides the instinctive appetites), is subjected to the sun’s thorough and destructive investigation.

The interrogation proceeds in the only way in which a vulture can conduct an investigation. Yet, despite the graphic realism of the “grapnel” claws, the probing eyes and the tearing “prehensile” beak, this bird is also a spirit from “the courts of the after–life”. Not only is she a terrifyingly real carrion–eating bird, she is also an “Efreet”, a spirit of the “ether”. Her “evidence” is the bloody remains of the “upside–down corpse” of the spiritual energies which the protagonist has devoured in his egotistical hunger. In an earlier version of the poem this last point is made more strongly:

The sun spies through her

…

Into the masks and amnesias

Of ego (ED).

It is the shell of the body, the ‘mask’, which this interrogator investigates and which “Her olfactory X–ray” penetrates, but this is not all that there is of Man. Hughes suggests this by his use of the generic term in the first line of the poem: it is “the stare–boned mule of man” which is to be interrogated, not, specifically, this stare–boned mule of a man. So, it is an aspect of human personality which is under examination rather than the behaviour of a particular man. The phrase “stare–boned”, too, captures the gaunt insubstantiality of the physical body which is a human being’s “concrete shadow”, whilst the paronomasia with ‘stubborn’ emphasises the mule–like qualities of the personality in question.

An earlier draft of the poem more clearly implies the vulture’s search for some spiritual, non–physical quality in the protagonist when it speaks of an ‘arsenic trace’, which is a common alchemical symbol for the soul:

And she will be raking the bowels for an arsenic trace

Of being at all (ED).

As the physical body dies, and the eyes glaze over and ‘chill’, only the fearful shape of the interrogator flickers before them, searching for some hint of continuing existence.

Baskin’s drawing for this poem emphasises the paradoxical blackness of this spirit from the sun. The realistic head and the hunched attitude of his bird are vividly vulture–like but the imaginative impression given by the picture links it strongly with the poem: the ‘humped robe’, the bloody instruments used in the interrogation and the aggressive attitude, are all apparent.

In this poem, for the first time, we see very clearly what Hughes described in his letter as the “human scenario” with the “disintegration of the female and the anaesthetised alienation of the male”35. For the first time, too, the enraged energies are personified in the form of a woman.

Only one other poem in the sequence, ‘Something was happening’(CB.30), links a man and woman in a similar domestic setting and gives the woman a human body and face (which is still “unrecognisable”). Both poems seem almost extraneous to the main action of the sequence; both seem to be additional, rather than integral, to the train of events36. They are, however, deliberately presented in this way so that they form, as Hughes puts it, a “static tableau” which shows a human parallel to the “phase of the relationship, between male and female, which is being dealt with, at that point, in the judgement of the birds”37.

Both the owl–like bird in ‘The plaintiff’ and the woman in ‘Actaeon’ are manifestations of Diana/Artemis, the Goddess of Nature. In ‘Actaeon’, the outraged Goddess appears in human form and her relationship to the protagonist (Actaeon) is made apparent by the way in which it is her face from which the hounds emerge to tear him to pieces (in the Greek myth the hounds belonged to Actaeon). The “leaves and petals of his body” form a link, too, with the leafy feathers of the bird in ‘The plaintiff’ which is described as the protagonist’s “heart’s winged flower”. The conflation of the male/female identities in both poems makes it apparent that we are being shown two aspects of a single being.

The reason that Actaeon, here, cannot see his destroyer’s face is because his own is a “blank”. Her hair is “Like his own” and “her voice / Which was a comfortable wallpaper” becomes, at the end of the poem, his voice, still “decorating the floor”. Only the contrasting imagery shows us the different nature of each persona. He thinks in terms of furniture, gadgets, carpets and hoover dust, “Staring, seeing nothing, feeling nothing”: her hands “produced food naturally” (a nicely ambiguous phrase) and her energy becomes “zig–zagging hounds” ranging the hills.

The merged identity of Actaeon and Diana, and the consequent self–devouring nature of the hounds’ attack, not only reflect the destructive aspects of love (such as Hughes dealt with in ‘A Modest Proposal’(THCP.27), ‘Lovesong’(THCP.255), and ‘The lovepet’(THCP550–2)), they are also important alchemical conventions. The ‘marriage’ of opposites – male and female, king and queen, sun and moon, Mercury and Sulphur – is an essential part of the alchemical synthesis, as is the self–devouring nature of Mercury, symbolised by the tail–eating dragon, Uroborus. Similarly, just as the alchemical process is cyclic and repetitive, so this poem describes, once again, dismemberment and death. Perhaps, however, Hughes decided that he had already made this point sufficiently in the earlier poems. He may also have felt that the overt use of Greek mythology in this poem did not sit well amongst his bird–beings and his less explicit blending of diverse mythologies in the rest of the sequence. For whatever reason, the poem was omitted from the published sequences.

Convinced of his guilt, the (protagonist) hero wishes only to understand it. But he is mystified: the Interrogator seems to be offering him an ambiguous atonement.

The vulture, as well as being a carrion eater, is a sacred bird. She is dedicated to the Great Goddess who, in her triple forms, is not only the feared goddess of death but also the Mother Goddess of fertility and of re–birth. As the representative of the Mother Goddess, the vulture, in ancient Egypt, was regarded as a compassionate purifier. In this poem, her compassionate role is paramount – she is

… the one creature

Who never harmed any living thing.

There are indications, now, that the enlightenment of the protagonist has begun. For the first time he sees and feels the horror around him, and he has moved, spiritually, beyond his friends so that he is able to see their “decay”, which has also been his own. They have become

… like dead things I‘d left in a bag

And had forgotten to get rid of.

The odour of death begins to pervade the poem. On his own hand, the protagonist smells “putrefying meat”(ED) and the process of self–accusation, the alchemical mortification and putrefaction, has begun.

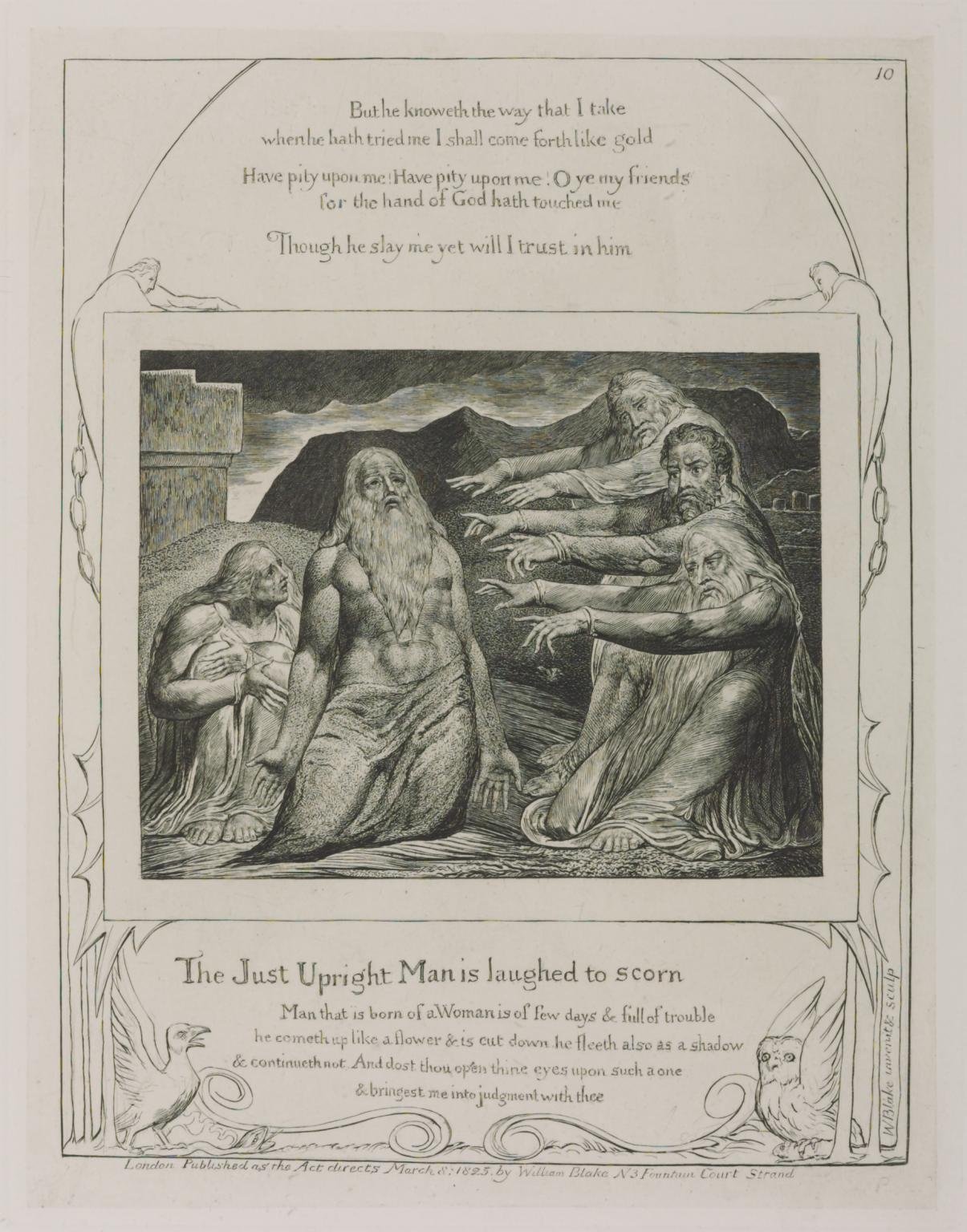

There are close analogies between this poem, the Biblical ‘Book of Job’, and Blake’s version of the story of Job. Like Job’s friends who “come to mourn with him and to comfort him” (‘The Book of Job’.II:11), the protagonist’s friends either sit, as if in judgement, being “twice as solemn” or they refuse to take him seriously. In The Bible, Job calls these friends “forgers of lies” and “physicians of no value’(Job.XIII:4); they are “mockers” who have “hid their heart from understanding”(Job.XVII:2,4) and he repudiates them. Blake, in his Job illustrations, depicts Job’s friends as self–righteous and accusing (Plate 10, below): these “corporeal friends are spiritual enemies” (Jer.Pl.44:10) and Blake surrounds his illustration of them with chained angels and “the cuckoo of slander, the owl of false wisdom, and the adder of hate”38.

Just as Hughes’ protagonist bites the back of his hand in mortification so the Biblical Job performs a similar action: “Wherefore do I take my flesh in my teeth, and put my life in mine hand? ”( Job.XIII:14). His transgression, too, is “sealed up in a bag” (Job.XIV:17), acknowledged and ready to be left behind.

Similarly, Blake’s Job, in the moment of enlightenment which Blake illustrated in Plate 9, acknowledges the rebuke of Eliphaz as a reflection of his own self–righteousness:

Shall mortal Man be more Just than God?

Shall a man be more Pure than his Maker?

In each case, after the fear and horror there comes recognition and acknowledgement of Man’s proud self-delusion.

Hughes’ protagonist, in his “voluntary solitary conflict”(ED), turns from his human friends to a plant. However, his relationship with even this “fellow creature”(as he calls it) is unequal and selfish: he treats it as his pet. With the death of this plant, the last element of the protagonist’s old egotistical world is stripped away. His response to this ‘‘dramatic’ moment is a melodramatic statement:

I felt life had decided to cancel me

(The same as it did with the sabre–tooth !(ED))

As if it saw better hope for itself elsewhere.

In contrast to his earlier assurance, the protagonist now feels that his place in the universe is threatened but the egocentric tone of his statement indicates how far from perfection he still is. The external forms of his world may have gone but a certain arrogance still remains in his personality.

Resigned and acquiescent, the protagonist accepts the motherly comfort which the interrogator offers and enters her embrace with relief. In the last two lines of the poem the two physical manifestations of the protagonist are again united: and Baskin’s illustration shows him bowed and flower–like, in the attitude of a bird sheltering an egg. He is wounded, perhaps mortally so, but uncrushed and the womb–like shape of the illustration conveys, also, the potential for re–birth which is suggested tn the final line of the poem:

Whether dead or unborn, I did not care.

‘Spider Piranha’/‘An Oven–Ready Piranha Bird’(ED)

‘An Oven-Ready Piranha Bird’39

Partaking of both cockerel(s) (?heaven or hood) and eagle(s) (?heaven or hood)(ED)) the visible representative of Natural Law does not partake of its splendour.

In this poem Hughes makes perhaps his strongest statement yet against a purely rational approach to life. His choice of phrases and symbols again provides links with Blake, and again he endorses Blake’s views of the distortion which the adoption of ‘unalterable’ moral codes brings into our lives.

Hughes’ Judge, wielding his god–like power in his “starry” geometrical web, reminds us of Blake’s comment that “The Gods of Greece and Egypt were Mathematical Diagrams”40. The stars, too, are fixed in his web like Blake’s fixed stars of Reason. Squatting against this mathematical backdrop, like a grotesque character in a morality play, the judge is an obscene example of the lengths to which Man’s pride may take him. His power is based on the arrogant belief that human eings are capable of correctly interpreting the laws of Nature and of using them to formulate ethical codes by which to judge their fellows.

Like the Emperor Nero, who was renowned as an egotistical, physically repulsive and ludicrous buffoon, this “Clowning, half-imbecile” creature has the power of life and death over those who come before him. This “representative of Natural Law”, restricted by (or, as Hughes ambiguously puts it, “Hung with”) the precedents recorded in the books of Law, acts as

…the filter across …

the word of God, to keep it pure, untainted, and stainless (ED).

Like a voracious cosmic spider, lolling about his court (which is both a judgement court and a banqueting court), the judge indulges his gluttony “for the crimes of others” (ED). Pondering and ponderous, his gross figure teeters and wobbles as he plays his unbalanced role, suppressing all who do not conform to his codes. Indulging his self–centred, destructive, reason–governed appetite he is deaf to all but “his digestion and the solar silence”.

Unlike the impartial keeper of the scales in the Judgement Hall of the Egyptian dead, Hughes’ Judge resembles, rather, hybrid monster, Amemet – ‘The Eater of the Dead’, who sits beside the scales to devour the hearts of those who fail the gods’ test41.

Baskin depicts the judge with a plucked, featherless, obese body (“oven-ready”), great raptorial claws, stunted wings and a ridiculously small head. There is a marked resemblance between this creature and the protagonist of ‘In these fading moments’, from whose mind, of course, he emanates. It seems that just as Blake’s Job created God and the Seven Eyes of God (including Elohim, the judge) in his own image (cf. the faces and attitudes of God and Job in Plate 5. for example). So Hughes’ protagonist has fashioned his own judge to conform with the chanced self–image which his accusers have produced in him.

‘Unfortunately for You’(ED)

It seems to the protagonist that the court is confusing his victim (who seemed to be his daemon (ED)) with some other personage, for whom he felt only love and concern.

This poem was included in sequence A and in the BBC broadcast of Cave Birds but it was omitted from the published sequences. It has been collected by Sagar and published as, ‘Your Mother’s bones wanted to speak, they could not’, in The Achievement of Ted Hughes (p.348). In the Exeter drafts it exists in two very different forms, the earlier of which is entitled ‘Unfortunately for You’. In both versions the protagonist is confronted with apparently incontrovertible evidence of his guilt.

The earlier version of the poem refers back to ’Actaeon‘ and it is the hounds of “the mother of creation” who lead the “winged furies” to the protagonist. As evidence of his crimes they carry “lumps of blood in their fists”. In both versions of the poem, the protagonist”s “paltriest words” and “fleetest imagination”, used in argument against the “dumb” evidence with which he is confronted, serve only to further implicate him.

Hughes introductory note describing the protagonist’s confusion as to the identity of his alleged victim constitutes a gloss on the texts. This confusion does not appear overtly in the poems, but hinges on the ambiguity of the word ‘mother’, which may be taken as referring to the Goddess as Mother Nature, or to the protagonist’s own biological mother. The conflation of the Goddess with some very personal figure in the protagonist’s life reflects the intimate connection which exists between the protagonist and the bird–beings which appear to him: they are visions which emanate from within him, prompted by his conscience and fashioned by his imagination.

These two poems, which are presented as a pair, appear only in the B sequence and have no accompanying notes. Both have been collected by Sagar and published in The Achievement of Ted Hughes (p.347). The first of the pair presents the protagonist as if facing interrogation by the Sun. The second, through obscure religious references, seems to show the Sun–being’s mutilation to be the result of Mankind’s repression of the early, nature–orientated religions by the introduction of the restrictive codes of a male god.

The first poem, with its references to “armour”, “fingers / Gauntletted[sic] with studded words” and “a vigil blade” forged by the sun, seems to look ahead to ‘The knight’ (CB.28). However, this dreamed knight’s weapons are of a quite different kind, and he, like the judge (CB.16), is constrained by words and reason. His brain is “buckled with fixed stars” and held “tight / In the status quo”. His world, like that of Mankind in Plato’s cave, is lit by reflection from the wall as he sits, “legs at east”42, awaiting the rising sun. This is his vigil, but although the blade across his knees is like the sun’s promise of renewed life, it is, also, the destructive weapon of a chivalric warrior, symbolic of the knight’s intention to uphold by force the codes of his belief.

Weighed down with such “obsolete armour” (‘The judge’ (CB.16)), the protagonist’s dreamed knight is yet connected by his spine (the living core of a man) to the earth: an essential part of him is still bound to the “sub–soil” of his subconscious from which his demons come to torment him.

The knight is transfixed, as if ready for sacrifice. This sacrificial imagery is carried into the second poem by the reference to Guy Fawkes, who is still ritually burned at the stake each November 5th in many parts of England. Guy Fawkes, however, is only the latest of a series of sacrificial figures who have traditionally been burned on the October/November Samhain bonfires which mark the end of the Celtic year. Samhain, like the Beltane festival in May, is essentially concerned with fertility rites and the Great Goddess. It is a time when the powers of Nature briefly have free reign in the world of Man.

Ritual sacrifice to appease the Great Goddess and ensure fertility for the new year was once a common Celtic practice, and it is the appeasement of the Goddess which is the common theme connecting the figures in the second of the protagonist’s dreams with the protagonist himself. Initially, Nebuchadnezzar, Guy Fawkes and St. John Chrysostom would seem to have nothing in common but all appear to have suffered because of oppression of the Goddess. In the case of Nebuchadnezzar and St. John Chrysostom, the argument for this view (presented below) is complex and obscure, which is perhaps why Hughes omitted these poems from the published and broadcast sequences.

Hughes’ poetic picture of Nebuchadnezzar is very like that shown in Blake’s etchings of this Babylonian king (MHH. Plate 24E43). Although a great king, Nebuchadnezzar suffered a period of insanity which is graphically described in The Bible:

… he was driven from men, and did eat grass as oxen, and his body was wet with the dew of heaven, till his hairs were grown like eagles’ feathers, and his nails like birds’ claws 44.

Blake believed that this bestiality was a punishment for idolatry and materialism45. He used Nebuchadnezzar as a symbol for oppression. Hughes, however, links Nebuchadnezzar’s suffering with the actions of St. John Chrysostom who, it is alleged in the poem, “stole a saintly kiss from God’’s mother”.

As in his poem ‘Logos’,(THCP.155) Hughes identifies God’s mother with the Goddess46. St. John Chrysostom (which means ‘golden–mouthed’ ) was renowned for his rhetorical powers, his rigid asceticism and his reforming zeal. His downfall was brought about by the Empress Eudoxia whom he initially supported and praised for her piety but later publicly denigrated as a ‘Jezebel’ for her love of luxury and personal adornment. Eudoxia, jealous of Chrysostom’s popularity and power, brought about his banishment and ordered the harsh treatment which eventually resulted in his death. In Hughes‘ terms, we can see in these events the conflict between harsh religious codes of behaviour and the natural desires of the female who represents the Goddess.

Despite this connection, the relationship between these events and the madness of Nebuchadnezzar is problematic. Not only did Nebuchadnezzar predate Chrysostom by some nine centuries but, apart from the fact that he was a dreamer and a religious oppressor, there is no clear relationship between him and either the protagonist or the Goddess.

In the end. whilst the overall feeling of these two poems seems to reinforce the theme of the impotence of rigid codes of thought and behaviour in the face of Nature’s vengeful powers, their inherent obscurities detract from their value to the sequence.

‘A Hermaphroditic Ephesian Owl’(ED)

‘A Hermaphroditic Ephesian Owl’47

His crime implicates him in wider and wider responsibilities. His victim takes on (a form which) is progressively more multiple and serious (deletion?) form (and a form) progressively more personal and inescapable forms. (Once again his victim is brought into court or rather something that has grown from the body of his victim, or rather victims, for it now seems that his victim is not simply his own daemon, or his mother, but a horde of aggressive ghosts, not excluding the many–breasted goddess herself. His crime is a (? sounding) hate – cheating his responsibility).(ED).

There are considerable differences between the broadcast (B sequence) and the published versions of this poem. In the former, Hughes turns to biblical and political symbols of repression for his imagery. Herod, Stalin, autos–da–fe and death camps are used to describe to the protagonist the enormity of his crime and the cruel hypocrisy of his self–deception. Blood and horror abound, and the creature which appears before him is “a holy creature of wounds”, a bloody “festering which your unconcern/Left to Mother Nature”, but which now, “engrossed in your image” is “come to supplant you”(ED).

In contrast, the poem in the published edition of Cave Birds has quite a different tone. Although the pain and the wounds are still apparent, there is also life, and beauty, and warmth. The bird in this poem “is the bird of light!”, “Your smile”s shadow”. She is no longer just “a bush of wounds” as in the broadcast poem, she is also “the life–divining bush of your desert”. Her feet, which were “as cold as anchors”, have become living “Roots”.

The terrifying, humbling aspect of the plaintiff remains the same in both poems, but in the published version she is much more than just “your blood–red flower”. Instead, as “Your heart’s winged flower“, she embodies the heart’s desires and hopes as well as its connections with life and blood.

The title of Baskin’s illustration, as well as Hughes’ introductory reference to “the many–breasted goddess”, makes it clear that the plaintiff is the virgin huntress, Artemis, who was worshipped by the Ephesians 48. She is Mother Goddess, Moon Goddess of fertility, child of Isis and Dionysus and twin of the Sun–god Apollo. Like Diana, Hecate, Calypso and the many other forms of the Great Goddess, Artemis‘ oracle bird is the owl – a bird of night, an omen of death and a bird of wisdom.

The owl symbolises the contradictory nature of the Goddess who controls birth and death and who can be both loving and vengeful. In ‘The plaintiff’, she embodies the contradictions of the protagonist’s paradoxical, unintentional harbouring of this creature within his body. Her hermaphroditic state suggests that she is the female part, the twin, of the protagonist himself. She is, too, the protagonist’s unconscious wisdom which will ultimately be his salvation.

Despite the overt reference to Artemis, the bird in Hughes’ poem has attributes which strongly suggest that an owl–goddess from his own native mythologies was influencing his writing. Hughes once remarked that the “deities of our instinct and ancestral memory”, the figures which are at the “roots” of an English writer or reader’s “genuine imagination”, are the deities of the Anglo–Saxon–Norse–Celtic mythologies. These gods he wrote of as being “much deeper in us, and truer to us, than the Greek-Roman pantheons that came in with Christianity”49.

So, perhaps it is not surprising that Hughes’ owl–goddess is very like Blodeuwedd, the owl–goddess of the Welsh Mabinogion 50. Just as Blodeuwedd was created by the magician, Math, from nine sacred flowers, so Hughes’ owl is a winged flower, with feathers like leaves and feet like roots. Just as Blodeuwedd was responsible for the death of her consort, Llew Llaw Gyffes, so the plaintiff has “Come to supplant” Hughes’ hero, who will subsequently, like Llew, be re–born51 . Blodeuwedd and Llew, like Artemis and Apollo, are the moon and the sun, the owl and the eagle, the twin aspects of Nature and (here) the twin elements of the protagonist’s personality.

The intrusion of Celtic mythology into these poems is not insignificant. for in the process of replacing Artemis and her bloodthirsty hound–pack with Blodeuwedd (flower–face), Hughes has brought warm elements of Celtic magic and enchantment into the poem. Moonlight, flames, leaves and flowers have beautifully supplanted blood, horror and destruction.

‘I called’(ED)

He comprehends some contradictions of his guilty innocence, and of his innocent guilt.

In the unpublished (B sequence) versions of this poem, the anaesthetised state of the protagonist is spelt out. He tries “to feel death” and “to feel life”, but he only feels distanced from the horrors he confronts. The animals accuse him or ignore him; his greatest shout is swallowed in a vast silence; and, as in the published version, the earth itself turns away from him and rejects him.

The published (A sequence) version presents a more complex argument. Like the dead who entered the Egyptian Halls of Judgement of the goddesses Isis and Nephthys (The Double Maati – sisters of Osiris), the protagonist offers a ‘Negative Confession’. In Egypt, a ‘Negative Confession’ was a ritual assertion by the dead person that certain sins had not been committed and that certain beneficent acts had been performed52. Hughes’ protagonist pleads “imbecile” innocence, setting himself apart from the horrors he relates so that he cannot be held responsible for them. His actions and emotions are those of an uninvolved observer. At the same time, the hyperbole of the phrases in which he describes his feelings marks them as the platitudes of social convention. He cries “unspeakable outcry” and feels “excess delight”: and even a small animal’s death “Lifts the head off” him. These are the sort of phrases which people use to imply their empathy with suffering whilst remaining aloof from it. They are very like the pleas which Job made and which Blake used to frame his fifth illustration of Job’s story (Plate 5, above): “Did I not weep for him who was in trouble. Was not my soul afflicted for the poor”.

In each case the pleas are no more than the excuses of one who can “put on righteousness” like a cloak (Job.XXIX:14), and they expose the self–righteous attitudes of those who make them.

Baskin’s drawing of the protagonist at this moment conveys all the blind arrogance of his condition. Standing naked before his judges, with his tiny head held aloofly (and ridiculously) in the air, he has the same gross body and raptorial claws which symbolised the judge’s greed; and his stunted wings indicate his unimaginative, Earth–bound state.

Whilst the protagonist makes his excuses, the plaintiff (who is, at once, the Great Goddess, Wife, Mother, Woman and Nature) continues to reiterate his guilt. As the “slip and trickle” of the anaesthetic ice which has imprisoned her becomes first “The snow-melt”, and then “brown bulging swirls”, we see the muddy chaotic waters of the protagonist’s subconscious surfacing and growing in strength. The final image of the poem suggests a human female turning her back on her male bed–mate, just as the plaintiff (the female element within the protagonist) displays her dominance over the protagonist. At the same time, the image captures the great natural upheaval which, in “The whole earth”, heralds the coming generative turmoil of springtime after the frozen stillness of winter:

The whole earth

Had turned in its bed

To the wall.

‘A Raven of Ravens’53

He is sentenced to death. The Raven of Ravens takes possession of him

Just as Baskin’s black bird fills the page opposite the poem, Hughes’ executioner gradually fills the world of his protagonist with darkness. His black shape moves across the face of the waters like the Spirit of God in Genesis(1:2) but he brings darkness, not light; chaos not order. He is the Raven, the oracular bird of all the mythological Sun gods, and Hughes (in the introduction to his next poem) identifies him as the Sun–god in his “aspect of judgement”. His poison, however, is that of the Great Goddess in her destructive form of Hecate.

With slow, repetitious measures the poem emulates the slow action of hemlock’s poison, tracing the gradual spread of the darkness as it obliterates first, the natural world and then, the protagonist. Imitating the path of hemlock–induced numbness in the body, the darkness begins at the protagonist’s feet and creeps slowly upwards until only his mind remains active.

Hemlock’s pattern of action is reflected elsewhere in descriptions of spiritual/sacrificial death, most notably in the Biblical description of Job’s trials. Tormented by Satan, whose nature is both destructive and, as Lucifer – the light bearer, creative, Job is smitten “with sore boils from the sole of his foot unto his crown”(Job.II:7). To see the parallel with hemlock in the pattern of this affliction it is only necessary to recall the common belief that boils result from poisons in the body. The death by poison which precedes spiritual rebirth takes, it seems, a very specific path in human beings: beginning with the death of feeling – the loss of awareness of the Earth beneath the feet – it moves inexorably towards the final surrender of intellect and of Spirit. Another example of this is offered by Eliot in Four Quartets where the “absolute paternal care” of the Saviour, like the ministrations of Hughes’ Sun–god/Raven, brings a death in which, again, “The chill ascends from feet to knees”54.

In Ancient Greece, hemlock was the poison chosen to dispose of convicted criminals. It was, therefore, the poison which Socrates was condemned to take. Plato’s description of Socrates’ last hours details the slow spread of the poison through his body until death ensues55. It describes, too. the sorrow which fills those friends who remain with Socrates and watch him drink the poison draught. Recalling this moment, Plato wrote:

hitherto most of us had been fairly able to control our sorrow: but now when we saw him drinking and saw too that he had finished the draught, we could no longer forbear, and in spite of myself my own tears were flowing fast; so that I covered my face and wept56

Just so, does the protagonist see the darkness “filling the eyes of” his friends. As the numbness fills him he feels that his body is no longer his own; that he has become a part of his executioner. Yet, this is not just an end, it is also a beginning. The presaged re–birth is suggested strongly in the final two lines of the poem in which the protagonist’s state of unbeing is described as feeling

… like the world

Before your eyes ever opened.

For permission to quote any part of this document contact Dr Ann Skea at ann@skea.com

Go To Next ChapterReturn to Poetic Quest Homepage

Go to Ted Hughes Homepage for more options