14

River

“the liturgy of the earth's tidings” (R.122)

An Addendum at the end of this chapter provides detailed notes about the origin of River and the difficulties leading to publication, based on correspondence between Ted Hughes, Peter Keen (photographer) and Olwyn Hughes (Hughes' sister and agent) which is now held in the British Library (Add.Ms 88615).

In River, Hughes turned again to Nature for his inspiration, and, choosing the watery interface where he had been most aware of her powers since childhood, he immersed himself and his readers in the primordial energies which abound there. Again, he undertook the hunting activities which, in the natural and the poetic worlds, were always his means of communication with the energies; and, in the river waters of this sequence, he literally and metaphorically found the Source of life.

In River, as in Remains of Elmet, Hughes’ vision of cosmic unity is presented through the actual. In the physical reality of Nature he saw the ‘perfect Whole’, as Blake did, in “Minute Particulars: Organized” (Jer.91:20–21) , and it is these ‘particulars’ which he recreates accurately and evocatively in his poems. His awareness of minute particulars extends, also, to the words, images and symbols that he chooses; and to the presentation of his work. In River, illustrations again play an integral part and, although the photographs by Peter Keen were not the inspiration for Hughes’ poems, they often “extend implications, deepen tragedy, heighten insights”, just as Leonard Baskin suggested illustrations should do1.

Hughes’ vision of the world, and the way in which he presents it, is holistic. In this respect, as Scigaj ably demonstrated, it closely resembles the world–view of many Oriental philosophies and of Taoism in particular (Scigaj passim). Yet, in his concern for the Oriental influences that he found in Hughes’ work, Scigaj overlooked the very Englishness of the world which Hughes’ poetry describes. Despite the universal applicability of Hughes’ beliefs and ideas, the concrete reality in which he grounds his imagery is overwhelmingly that of the English countryside. In addition, his poetic techniques and his ideas clearly owe much to the long history of English poetry and poets, and a constant shaping influence on his work was his English/Celtic background. New ideas, environments and experiences added new dimensions to Hughes’ beliefs, which remained remarkably consistent over the years, but his work continually demonstrated the deep and persistent influence of his own ‘Anglo–Saxon–Norse–Celtic’ heritage.

Hughes’ strong belief in the entrenchment of this particular heritage in the English “blood” are expressed in ‘Asgard for Addicts’ (WP.40–1). And Hughes’ Goddess clearly belongs to the pre–Christian “deities of our instinct and ancestral memory”, where “our real mental life has its roots, where the paths to and from our genuine imagination run”. In all his varied representations of her, she typifies the description given by Anne Ross, in Pagan Celtic Britain, of “the basic Celtic goddess type”. She is

mother, warrior, hag, virgin, conveyor of fertility, of strong sexual appetite… giver of prosperity to the land, protectress of the flocks and herds (Ross.232–245)2.

Her presence gives the natural world which Hughes describes mythical and sacred dimensions, but it brings it, also, disruptive primitive and pagan energies. Because of this, the uncompromising realism of Hughes’ picture of Nature often seems excessively and disturbingly explicit. Yet, the constant and inseparable presence of life and death, the perpetual “travail of raptures and rendings” (R.122) which inform Hughes’ perception of our mutable world (especially in the Moortown Elegies, which were published in the same year as Remains of Elmet), convey the combination of beauty and horror in Nature which evinces the presence of the Goddess.

River, in particular, shows the inspirational influence of Hughes’ own Celtic divine ancestor, Brigantia (‘High One’), a powerful Celtic goddess widely associated with rivers and with healing and fertile waters. Her territory spread far beyond Elmet to the whole of the North of England, and was probably even wider, since her name relates her to the Old Irish goddess, Brigid (later St. Bride), who was worshipped all over the British Isles3. Appropriately, Brigid is not only a goddess of rivers and wells, she is also described in the Celtic Irish sagas as “a woman of poetry, and the poets worshipped her”4. Her presence eddies and flows through River, enduring and changeable as the river–waters themselves which, for the Celts, were a “physical personification of the goddess, mirroring her own supernatural forces – strength, the powers of destruction, fertility”5.

She is fickle and subtle, sensuous and evil, young and old, and two–faced, like Brigid, whose description in the sagas asserts that “one side of her face was ugly, but the other side was very comely” (Gregory.28).

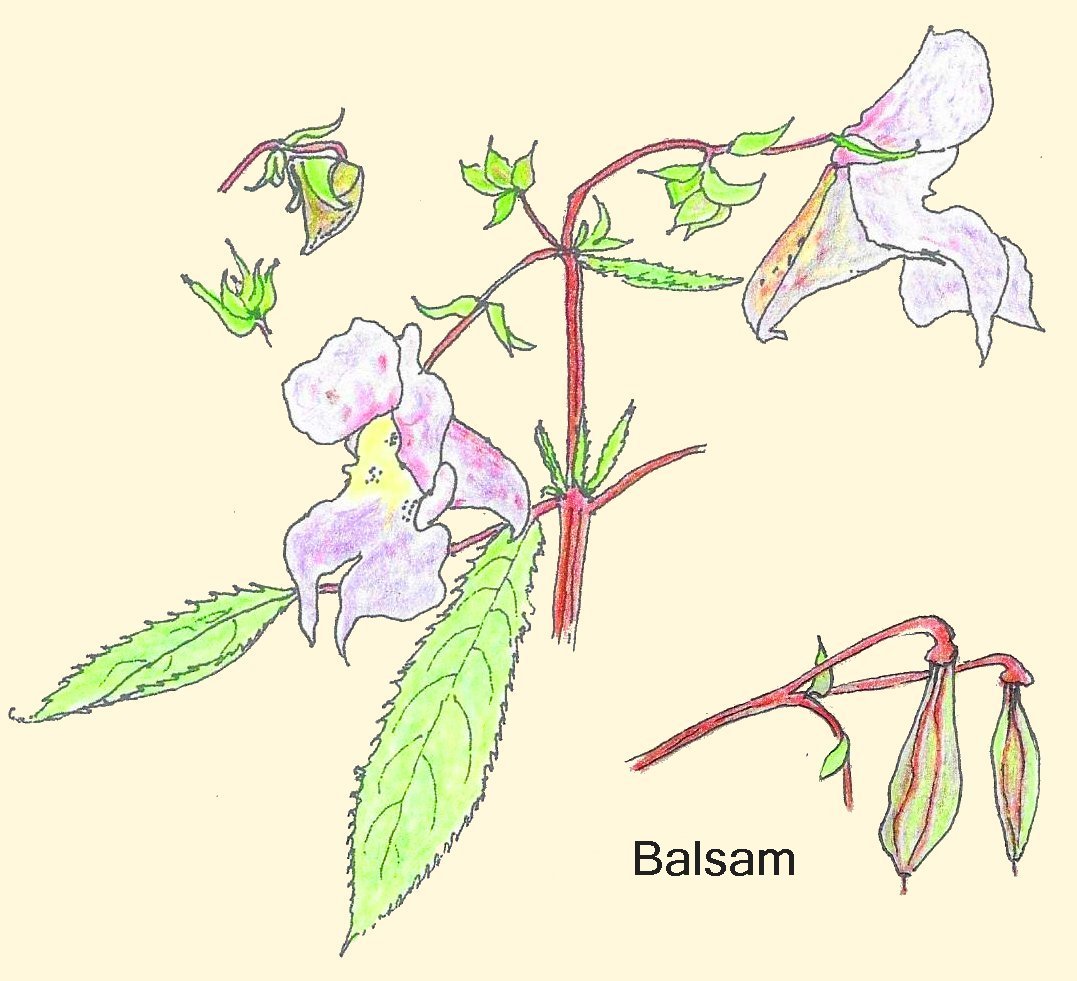

At times, in River, she may be “a beautiful idle woman” stirring “her love–potion – ooze of balsam / Thickened with fish–mucous and algae” to seduce her lover to “copulation and death” (R.88): or else, an “evil” witch in “the drought river of slimes”, “old–blood dark”, creating “sick–bed darkness” with her “hangings of hemlock and nettle, and alder and oak” (R.76). She may be a “brown musically–moving beauty”, a lithe daughter “remorselessly” fleeing her distraught and bleeding Earth–father (R.106): or a welcoming “grandmotherly” spirit, whose reassuring presence nevertheless exudes “a fishy nostalgia” for some sultry and exotic past (R.102) (the word ‘fishy’, here, beautifully captures the slightly suspect sweetness of the grandmother as well as her connection with the river).

At times, in River, she may be “a beautiful idle woman” stirring “her love–potion – ooze of balsam / Thickened with fish–mucous and algae” to seduce her lover to “copulation and death” (R.88): or else, an “evil” witch in “the drought river of slimes”, “old–blood dark”, creating “sick–bed darkness” with her “hangings of hemlock and nettle, and alder and oak” (R.76). She may be a “brown musically–moving beauty”, a lithe daughter “remorselessly” fleeing her distraught and bleeding Earth–father (R.106): or a welcoming “grandmotherly” spirit, whose reassuring presence nevertheless exudes “a fishy nostalgia” for some sultry and exotic past (R.102) (the word ‘fishy’, here, beautifully captures the slightly suspect sweetness of the grandmother as well as her connection with the river).

Hughes’ Goddess in River takes many forms. As the land and the elements personified she becomes a snowy “juicy bride”, joined in a sensual, sexual embrace with the river (R.14); she is a mother, whose breasts are the hills where flowing springs form “the shining paps that nurse the river” (R.30); or she is a goddess, whose son, a sacrificed god “fallen from heaven, lies across / The lap of his mother” (R.74) as in a pieta. She is present, too, as the river creatures, linked to them by Celtic and other mythologies but always embodied in animals, birds and insects which are part of the English countryside. She is there in the “merry mink” (R.32),

which shares its ancestry with Hughes’ Otter (THCP.79), with the weasels in Remains of Elmet (ROE.63), and with the mysterious “dark other” whose “pad–clusters”, like the mink’s “stars”, dot the river margins at dawn (R.116). Her energies fill the ghostly white heron (R.20) and the “abortion–doctor” cormorant (R.90), the hermaphrodite eel and the long–legged, predatory insects – the Damselfly (a “dainty assassin” in her “snakeskin leotards” (R.96)), the “blood–mote mosquito”(R.84), the midges, and the spiders which lurk, watchful and industrious, in several of the poems (R.56,26,96,120). The Goddess is amongst the flowers, too, her nature expressed in the “too fleshy perfume” of the Hawthorn (R.20) and in the heavy “nightfall pall of Balsam” (R.96); in the exuberance of primroses and “wild, stumpy daffodils” (R.22); and in the threat of the honeysuckle’s “fangs” (R.68).

which shares its ancestry with Hughes’ Otter (THCP.79), with the weasels in Remains of Elmet (ROE.63), and with the mysterious “dark other” whose “pad–clusters”, like the mink’s “stars”, dot the river margins at dawn (R.116). Her energies fill the ghostly white heron (R.20) and the “abortion–doctor” cormorant (R.90), the hermaphrodite eel and the long–legged, predatory insects – the Damselfly (a “dainty assassin” in her “snakeskin leotards” (R.96)), the “blood–mote mosquito”(R.84), the midges, and the spiders which lurk, watchful and industrious, in several of the poems (R.56,26,96,120). The Goddess is amongst the flowers, too, her nature expressed in the “too fleshy perfume” of the Hawthorn (R.20) and in the heavy “nightfall pall of Balsam” (R.96); in the exuberance of primroses and “wild, stumpy daffodils” (R.22); and in the threat of the honeysuckle’s “fangs” (R.68).

In River, as in all Hughes’ other work, the Goddess’s presence is all pervasive; but sharing equal prominence with her in this sequence are the fish – Salmon and Trout – which “worship the source, bowed and fervent” (R.118). These are the shamanic guides which move at will through the fluid, mercurial interface between this world and the Otherworld of the imagination, drawing Hughes with them. They are the familiars of the Goddess, gaining their life and energy from her waters, absorbing her magical and sinister powers, and sharing her duplicity. They, too, were revered by the Celts, because of their kinship with the five sacred salmon of Celtic mythology who once fed on the fruit of the nine hazels of wisdom, inspiration and “the knowledge of poetry”, that grew over their “well beneath the sea“6

Hughes clearly shares the Celtic reverence for these fish, which he describes as ‘holy’ and magical. Like the Celts, he links them closely with inspiration and poetry. For him, however, it is not eating the fish which “brings all knowledge and all poetry”, (as the Celts believed7),but the ritual pursuit of them, the primitive hunt undertaken with a bagful of “lures and hunter’s medicine enough // For a year in the Pleistocene” (R.38).

Hunting, whether for fish or for poetry, was Hughes’ passion; and it was the means by which he effected the “time–warped” (R.50) movement between one reality and another such as he describes, for example, in ‘Go Fishing’ (R.42). This was the “ancient thirst” (R.56) which drew him to the “brink of water” where Celtic poets, too, thought “poetry was revealed to them”8. In River, water is “the generator”, “the power line”, “a chrism of birth”, “The medicinal mercury creature” (R.16), and Hughes soaked up its refreshing energy

through every membrane

As if the whole body were a craving mouth,

As if a hunted ghost were drinking – sud–flecks

Grass–bits and omens

Fixed in the glass. – ‘River Barrow’ (R.56)

In River, the “river–fetch” exerts a hypnotic attraction which can whirl him into the vortex like

the epileptic’s strobe,

The yell of the Muezzin

Or the “Bismillah!”

That spins the dancer in… – ‘Riverwatcher’(R.108)

It can lull him with its “smooth healing” peace, and leave him “half–unearthed” (R.56). Yet, it is the encounters with the fish, real or poetic, which activate Hughes’ primitive hunting energies. It is these encounters which revive the telepathic (R.38) link between hunter and hunted (“Eerie how you know when it’s coming!” (R.48)), and provide a new, energising exposure to the dangerous, scalp–prickling, necessary, primordial and primeval powers.

In the watery abyss, the fish are “rainbow monster–structures” (R.42). A young, fertile, cock salmon, “brindled black and crimson, with big precious spots” (R.10), ages to become “King salmon” (R.84); but by “Four years old at most” it is “already a veteran, / Already a death–patched hero. So quickly it’s over!” (R.110). Yet, even with bleeding gills, and with its, “red–black almost unrecognisable” and its “dragonized head”, it is still “A god, on earth for the first time, / With the clock of love and death in his body.” (R.64). There are mythical dimensions to these creatures, too, suggestive of sacrificed gods, and in Hughes’ descriptions of them there are echoes of Blake’s vision of the “monstrous serpent”, Leviathan:

his forehead was divided into streaks of green & purple like those on a tygers forehead: soon we saw his mouth and red gills hang just above the raging foam tingeing the black deep with beams of blood, advancing towards us with all the fury of a spiritual existence. (MHH.18:28–33).

So, each encounter with fish becomes a rehearsal of the mythical confrontation with the marine–monster Tiamat/Leviathan, the serpent of chaos and creation: a new acknowledgment of the destructive/creative powers which pervade our world, and which must repeatedly be faced and reconciled by each of us. Beneath the mercurial “water mirror“ (R.56) which draws Hughes to its edge with its “solid mystery”, in the “sliding place” (R.56) where imagination and reality, subconscious and conscious, meet, there lurk submarine monsters. Their “Torpedo / Concentration”, “mouth–aimed intent” and “savagery” await him in a menacing stillness (R.62) disturbed only by their pulsing gills. Hughes’ awareness of these watchful predators, and his references to prehistoric geological and mythological eras9 create an atmosphere filled with primitive terrors into which he ventures with trepidation, a “pilgrim for a fish” (R.80), confronting and conquering his fears like a questing hero and returning, ultimately, to create poetic order from a chaos of sensations and thoughts.

Typically, the fish which Hughes hunts in River and elsewhere – Salmon, Trout and Pike, and even the predatory luminescent deep–sea fish, Photostomias, of which he wrote in Moortown (THCP.549) – do have a factual connection with prehistoric geological eras. All, until very recently, were included in the biological Order, Salmoniformes, from which all present bony fish are thought to have evolved10. All differ little in form from their fossil ancestors, which provide the first evidence of the existence of marine vertebrates. It is believed, too, that from such marine vertebrates as these, terrestrial vertebrates evolved11. So, Hughes calls these fish, with some justification, “my fellow aliens from prehistory” (R.46) and “Miraculous fossils” (R.80). And it is equally typical of the care and precision of Hughes’ work, that his choice of the latter epithet should convey more than the ‘miracle’ of these creatures’ lineage, being linked, as it is in ‘Gulkana’ (R.80), with the eternal, the mythical and the holy.

In River, the ‘miraculous’ aspects of the fish have very little to do with their importance to science. Rather, they stem from Hughes’ own special reverence for the fish and the connections which they facilitate for him between his inner and outer worlds. By re–enacting his encounters with the fish, Hughes remakes these connections and, in so doing, creates his poems. He also attempts to share his experience with others by involving them imaginatively in the process and, thereby, transmitting to them some of the fishes’ power. In effect, the fish, like other aquatic creatures in Hughes’ work, become powerful and functional symbols of hope. They provide a natural example of reconciled energies and they facilitate such a reconciliation in Mankind. In his poems, Hughes exploits their biological, geological and mythological significance to give them the imaginative life and energy they need for this purpose.

The extent of the power which Hughes ascribes to fish can be judged by examining the Moortown poems, ‘Photostomias’ 1,2 and 3, (THCP.549) , whilst keeping in mind his beliefs in the nature and imminence of the primordial energies. Photostomias are “small, predatory, luminous fish of the great deeps”, creatures of the ‘roofless Gulf–cellers”, and in them Hughes finds the perfect natural symbol for reconciled contradictory energies. Each fish is literally a light–bearer of the dark abyss, a grotesque creature of horror and of beauty, which Hughes calls “the radiant host” akin to “the tiger / In his robe of flames”.

Like Blake’s tiger12, and like Hughes’ own tiger in ‘Tiger Psalm’ (THCP.577), it is an embodiment of contraries. And, like every tiger, it is part of the natural order, an exquisite balance of form and function: it eats and is eaten – is “A feast charged with lights, / Searching for guests” but death in its jaws is “apotheosis”, resorption into the divine cosmic order So, like the tiger in ‘Tiger Psalm’, it “blesses with a fang”; it kills and “Does not kill but opens a path / Neither of Life nor of Death” but to a vision of paradoxical unity through which we may glimpse the perfect whole.

Like Blake’s tiger12, and like Hughes’ own tiger in ‘Tiger Psalm’ (THCP.577), it is an embodiment of contraries. And, like every tiger, it is part of the natural order, an exquisite balance of form and function: it eats and is eaten – is “A feast charged with lights, / Searching for guests” but death in its jaws is “apotheosis”, resorption into the divine cosmic order So, like the tiger in ‘Tiger Psalm’, it “blesses with a fang”; it kills and “Does not kill but opens a path / Neither of Life nor of Death” but to a vision of paradoxical unity through which we may glimpse the perfect whole.

With punning accuracy, Hughes calls Photostomias, “the radiant host”: communion with them may enlighten our own dark, spiritual depths, just as they light the watery depths of our planet. Each is a “Buddha–faced”, a “Jehovah”, “A decalogue / A rainbow”, a sign and a promise of some greater, divine order: and, like the salmon in River, each of these “creatures of light” (R.72) may be seen as a manifestation of the polymorphous Hermes/Mercury, whose guiding, spiritual light constantly illuminates Hughes’ work.

Photostomias, as Hughes makes clear, are not unique in the guidance and promise they offer. Not only do their close relatives, Salmon and Trout, share their ‘holy’ and sinister powers and impart their own blessing, enlightenment and apotheosis (as the massed salmon do in ‘That Morning’ (R.72) ), but such qualities are present also in Nature’s more common and seemingly ordinary creatures. Strange and rare as Photostomias may appear in their inhospitable environment, they are no more miraculous a manifestation of “the organising and creative energy itself” (WP.92) than any other living thing. They are

… no further

From belief’s numb finger

Than the drab–jacketed

Glow–worm beetle, in a spooky lane,

On a wet evening.

The Peacock butterfly, pulsing

On a September thistle–top

Is just as surely a hole

In what was likely.

Each life form is equally a miraculous crystallisation of cosmic energy; a “star–hardened“ miracle of survival, like the “miserly heather–flower”, (cf.‘Heather’ in Remains of Elmet). Each is, also, part of the perpetual cycles of death and rebirth, and we may glimpse beneath each “created glory” (WP.13) the death and horror which are a necessary part of its existence in this “fallen World” (which is what Hughes calls our own world in River (R.72) ). Because of this, Hughes turns constantly to Nature in order to demonstrate the necessary and harmonious interaction of contrary energies in Earthly existence. In particular, however, it was always the birth of beauty from horror, the relationship between renewal and sacrifice, mana and death, and the creation of spiritual gold from earthly dross, which fascinated him and which lay at the heart of his beliefs and his work.

Beneath the wonder of natural life, Hughes was aware, always, of the necessity and inevitability of death. Our own awareness of this (whether conscious or subconscious) may cause us fear and horror, but Hughes believed that we are aware of something more – a divine horror which is, in Lorca’s words, “beyond death” (WP.92) – and it is this he discussed in his essay on Baskin’s art, ‘The Hanged Man and the Dragonfly’ (WP.84–102). As well as finding it in Nature, Hughes also discovered this divine horror in great art and music. Attempting to define it, he called it, in his Baskin essay, “a secretion from the gulf itself”, an exudation of the “ineffable, infinite affliction of being” which connects, “as it seems, everything to everything, and everything to the source of itself” (WP.92) . This is Lorca’s Duende which, Hughes wrote, lies at “the core of life, like the black ultimate resource of the organism”; and it is mana – the healing “ectoplasmic essence” for which payment must be made through suffering but which Hughes described as “more than metaphorically, redemption incarnate”.(WP.93).

In many ways, Hughes’ discussion of the source of inspiration in Baskin’s work, applied equally to his own. His quest for understanding of our world and our position in it was also the quest for mana; and the forms which this took in Hughes’ work over the years conformed to his own assessment of epic as “the story of mana”(WP.100). Epic, according to Hughes, displays recognisable patterns which parallel the ‘saga’ of “the search for and finding of mana”, and these recur in

three historically familiar forms, with religious quest as the most civilised form, and heroic epic as the barbaric form, and the shaman’s dream of his flight as the prototypical and, as it were, biological form (WP.100).

Since Wodwo, Hughes poetic questing had conformed to these patterns of epic: and, whatever the truth or validity of Hughes’ beliefs, his certainty that some great, healing, cosmic force exists could, after Cave Birds, no longer be doubted. This force is the source of renewal which he tried to reach by deliberately exposing himself to the daemonic intensity and the “sinister beauty” (WP.89) of Nature both in his life and in his work: and it is this sinister beauty which pervades Remains of Elmet and River.

River combines all the “historically familiar forms” of epic of which Hughes wrote. Elements of religious quest, heroic epic and shamanic flight are all readily apparent. This is the “river–epic” (R.28) in which Hughes sings “the liturgy / Of the earth’s tidings” (R.122) and which is, ultimately, a creation of beauty and hope – an optimistic assertion of everlasting healing and renewal in a cosmos where “Only birth matters” (R.124). In his river–epic, Hughes seeks mana, the energy of the creative–destructive Source, in as many ways as he can. His evocation of the Goddess and her realm; his use of mythology (the Celtic mythology of his heritage, in particular); his care and concern for the musical elements of his work; and his persistent efforts to activate all our senses, are essential to his task. Besides these, there are elements of religious devotion, heroic quest, shamanic flight, alchemical transmutation, and the activation of the most primitive human energies, all enmeshed in the cosmic patterns which govern our existence. All of these elements become part of a flux of energies which mingle, like the organic elements of Nature, to create the river epic, and it needs only a close examination of a few poems to appreciate the skill with which Hughes achieves this.

Fundamental to the healing purpose of the river–epic, is the representation of water as the source of life itself. This not only reflects Mankind’s most primitive cosmogonic beliefs, as expressed in mythology and religion, it is also a currently accepted scientific ‘fact’. In ‘Flesh of Light’ (R.16), Hughes uses cosmic and alchemical imagery to describe the river’s origin and purpose, creating from its shining, reflective surface and its fluid, sinuous flow, a materialisation (a ‘flesh’) of elemental and spiritual light.

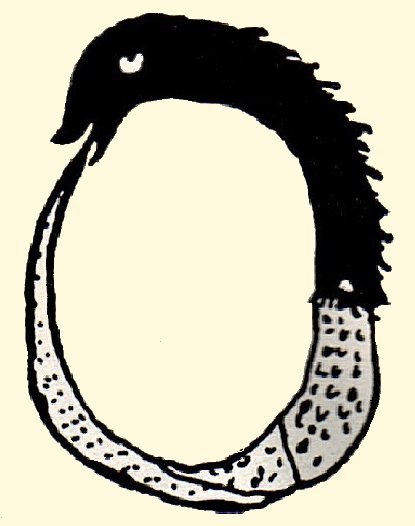

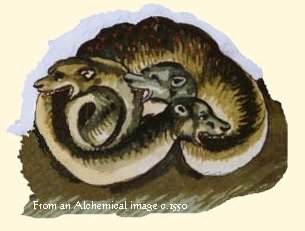

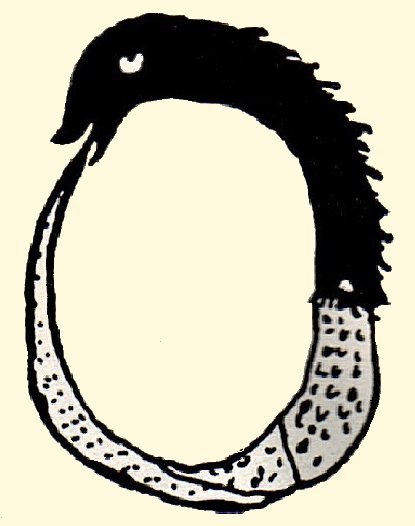

The water, which is a “smelting” from the cosmic “core”, “brims out lowly for cattle to wade”, and the double meaning of ‘lowly’ as both ‘down low’ and ‘humble’ links heaven and earth, the divine and the mundane. But the water is also the “medicinal mercury creature”, the mythical, “fallen”, cosmic snake of chaos and renewal, with “inscribed scales / That it sheds / And renews” – the ouroborus, which Alchemists adopted as a symbol of the alchemical process of enlightenment and re–birth.

The water, which is a “smelting” from the cosmic “core”, “brims out lowly for cattle to wade”, and the double meaning of ‘lowly’ as both ‘down low’ and ‘humble’ links heaven and earth, the divine and the mundane. But the water is also the “medicinal mercury creature”, the mythical, “fallen”, cosmic snake of chaos and renewal, with “inscribed scales / That it sheds / And renews” – the ouroborus, which Alchemists adopted as a symbol of the alchemical process of enlightenment and re–birth.

Using imagery which combines light and energy with their natural and material manifestations on Earth, Hughes conveys the pure light/energy character of water. From the “core–flash” (suggesting the ‘Big Bang’ creation of the universe) and the resulting atomic dance, comes the fluid “power–line” that carries this energy to Earth and brings the dry “bones” life. Remaining faithful to scientific concepts of energy transfer, Hughes suggests the conversion of light to electricity, the precipitation of rain, and the biological utilisation of light and water to produce energy, but his imagery is far from coldly scientific. Amidst the initial chaos of creation he pictures something alive and beautiful that “crawls and glimmers among the heather–topped stones”, then “brims out” in abundance “for cattle to wade”.

The abundance spills over into Hughes’ next image, which is as dense with meanings as the dark, warm bodies of the cattle are “dense” with the life–giving energy they imbibe. Lifting their streaming muzzles from the water, the cattle “unspool” it as if unwinding the thread of life, and Hughes’ use of the word “glair”, its association with egg albumen and its paronomasia with ‘glare’ (meaning ‘dazzling light’), convey the importance of the role that cattle play in the transmission of the life–energies. It is this fecundity of association, as much as the power and beauty of the cattle image, that suggest the presence of the Goddess, whose mythological representation as a cow is ancient and widespread.

There is a religious aspect to the creative powers of the water, too, introduced into the poem by the use of words like ‘chrism’, ‘anoints’ and ‘aura’; words which are more usually associated with religious ceremonies but which, here, convey the spiritual nature of the medicinal mercury creature and give greater meaning to the “blossoming” it engenders. Similarly, by choosing the word ‘blossoming’ Hughes not only suggests the creation of something beautiful, he also creates resonances with his use of this word in earlier poems where he links it with symbols of mana: his own tiger, for example, is a “Beast in Blossom” (M.578) ; and the Earthly light–bearers in ‘Photostomias’ are

Blossoms

Pushing from under blossoms

From the one wound’s depth

Of congealments and healing – (THCP.549).

So, the blossoming of the sea in ‘Flesh of Light’ is an image which conjures more than the evolutionary blossoming of Earth following its creation: it conveys, also, a promise of healing, re–creation and continuance.

Finally, there is an aspect to the poem which is consistent with its primary position in the sequence in the American, Harper & Row, edition, and which is shared by ‘The Morning Before Christmas‘ (R.8) , the poem which holds primary position in the English edition of River. It is an aspect which is closely connected with Hughes’ alchemical/shamanic purposes in Cave Birds and Remains of Elmet, and it has much to do (as will be explained) with traditional religious faith in the power of sacred rituals to transcend the material dimension of their origin and to renew Mankind’s link with the divine. In both ‘Flesh of Light’ and ‘The Morning Before Christmas’, Hughes uses poetic ritual to re–enact creation. In the first poem, Hughes begins by describing creation on a cosmic level, then moves to the delicate potential of Earthly life – the “unfolding baby fists” of the ferns and the eye–like fish–eggs in the “throbbing aura” of the river water13. Except for the poet, humans play no part in these events. The second poem, however, describes a ritual in which humans act a god–like part, performing “solemn”, “precarious obstetrics” which will ensure an abundance of salmon. Thus, they participate in the creation of life on Earth, an event which Mircea Eliade describes as “the central mystery of the world”14. Other of Eliade’s views may, perhaps, give us insight into Hughes’ likely purpose in beginning his poetic sequence with such ritual recreations, for there is much in The Sacred and the Profane that is relevant to Hughes’ work in general and to River in particular.

Hughes’ view of Nature as a living organism, and his belief in the knowledge and enlightenment it can show us, accord well with the view of the world which Eliade attributes to “religious man” (the term is used in its broadest sense as applying to one who acknowledges some superhuman, omnipotent, omnipresent power). “For religious man”, Eliade writes,

Nature is never only ‘natural’; it is always fraught with religious value … the different modalities of the sacred [are manifested] in the very structure of the world and of cosmic phenomena.

The earth … presents itself as universal mother and nurse. The cosmic rhythms manifest order, harmony, permanence, fecundity. The cosmos as a whole is an organism at once real, living and sacred; it simultaneously reveals the modalities of being and of sacrality (Eliade.116–7).

The similarity of these views to Hughes’ beliefs is clear. What is not so clear, perhaps, is the resemblance between the epic of the river’s year which Hughes presents in River, and the annual festivals and rituals which Eliade describes as being practiced by religious man in order to re–actualise primordial, mythological and sacred time and ensure the continuance of the world.

Sacred time, Eliade stresses, is cyclical and reversible, and he observes that “for religious man of archaic cultures” not only is the world annually renewed, but it is resanctified:

with each new year it recovers its original sanctity, the sanctity that it possessed when it came from the Creator’s hand (Eliade.75).

Through religious ritual, Mankind attempts to re–establish cosmic time and to briefly enter the eternal dimension, communicate with the divine, and share its powers. Annual religious festivals, therefore, are more than a ritual performance of “acts and gestures” which “imitate the paradigmatic models established by the gods and mythical ancestors”. They are also a ritual recovery of primordial time by means of which people ensure that the world is renewed and resanctified.

In the poems with which Hughes has, in different editions, begun his River sequence, there are recognisable parallels with this ritual re–creation of the world and of life on Earth. ‘The Morning Before Christmas’ (R.8), in particular, resembles one of the most widespread of annual religious festivals (and one which is discussed by Eliade in the above terms): that of the ritual cultivation of important food, by means of which Mankind ensures the fertility of the land. The slow penetration of the sun’s warmth into the “brand new stillness” of the dead and frozen world; the rhythmic, precise, and painstaking actions of the men collecting the “vital broth” of eggs and sperm; the solemnity and beauty of the poem’s atmosphere and music; and the way the events and the poem are marked with the prints of the fox (a symbol of fecund life–energies of particular significance to Hughes since ‘The Thought Fox’ (THCP.21) ); all these things suggest the ritual and spiritual nature of the events described.

As Hughes’ river–epic progresses through its annual cycle, other ritual re–actualisations of cosmic time occur: the mating of the gods, in ‘Japanese River Tales’ (R.14), for example; the “resurrection”, in ‘Under the Hill of Centurions’ (R.36); the battle with the marine monster, in ‘Gulkana’ (R.80); and the sacrificial death of the god–‘hero‘, in ‘October Salmon‘ (R.110) . Hughes, therefore, appears to ritually re–enact the primordial, mythical paradigms in the River sequence and, in so doing, he confronts the inherent dangers which exposure to the primordial energies involves. Through such encounters, through his own involvement in the events the poems describe, and through his creative striving, he voluntarily makes the payments which the life energies, the mana, demand. And, just as the river waters channel the source energies “to the roots” (R.16) of the Earthly sea and bring about its ‘blossoming’, so the flow of Hughes’ poetic sequence seems designed to channel the life–energies of the sacred rituals into the sea of the human imagination to create another, more spiritual blossoming.

From whatever aspect of Hughes’ thought one approaches River, it is soon apparent that the waters were for him, as they have always been for religious man, the ultimate source of life, energy and renewal15. The natural rhythms of the river’s year provided him with a unifying theme and a rich source of natural imagery: and by linking these rhythmic patterns to events in the cosmic year, and weaving into them allusions to common religious and mythological epics, he achieved a broader, healing purpose and made this work an extension of the shamanic/alchemical task he undertook in Cave Birds and Remains of Elmet. It is unlikely, therefore, that the sequence resulted simply from Peter Keen’s “desire to photograph a river, source to mouth, through an entire twelve–month cycle”16: especially since the Elmet poems concerning Hughes’ encounters with fish in the waters of the Calder Valley seem clearly to prefigure the move in River towards direct poetic exploration of the aquatic interface between physical and metaphysical worlds. In effect, the waters in River become the cosmic Centre of Hughes’ world: through them he enters dimensions which extend beyond the physical and the temporal; and, in these moments of altered perception, it is fish which are his most powerful shamanic and imaginative guides.

In River it is clear, too, that Hughes’ previous poetic ventures into the metaphysical world had given him confidence in his beliefs and powers. In these poems, he moved directly to the source of his inspiration, wholly committing himself to an epic journey in which the cosmic rhythms of Nature drew him deeply into the world of pure energy and spirit. By carefully shaping the River sequence around these cosmic rhythms, he facilitated intimate contact with the energies from which his poems flow. He also achieved a protective ritual framework which allowed him to share in the regenerative energies he evoked: a necessary precaution, since these poems brought him closer to their dangers than ever before.

Such religious and ritual aspects in this sequence suggest that it is a mistake to identify Hughes too closely with its fisherman persona, for, although he frequently reflects Hughes’ own difficulties, emotions and concerns, this persona is essentially an epic hero – a sensitive pilgrim who provides the human perspective in the river scene, and with whom the reader, as well as the poet, can identify.

Like the questing Everyman hero of Cave Birds, Hughes’ fisherman–poet–persona in River is initially hampered by his analytical mind, his limited perspectives, and his closed senses. Fundamental to his quest for unity with Nature is his need to reconcile the disparate aspects of his being. He is, however, aware of his difficulties; and aware, too, of his own primitive hunting instincts and the way in which these link him with the elemental energies. Throughout his quest, the fish, and especially the salmon, are his totem creatures: their ability to return unerringly to the source of their existence parallels his own epic quest for the source of truth and knowledge. So, he holds them in special reverence, empathising with their suffering and struggles, and seeing in them the “epic poise” (R.114) and the acceptance of sacrifice which he, too, must learn in order to be part of the “machinery of heaven”. Seeking their knowledge and guidance, he hunts for them as if they held the Grail or the Philosophers’ Stone.

Just as the annual return of wild salmon and trout to the river is governed by the machinery of Heaven, so humans, too, are subject to the natural rhythms. The poet–persona in River is demonstrably affected by Nature’s powers in the early poems, and his struggles for direct communion with the energies end with the moment of spiritual communion which occurs in ‘That Morning’ (R.72). Like the salmon, his physical energy increases as the sun’s power strengthens, then fades as the year moves towards its close: and, like the salmon, his journey, his struggles and the sacrifice, must be constantly repeated.

The poet–persona’s responses to Nature begin in the opening poem of the Faber edition. At the first melting penetration of the sun’s life energies into the frozen mid–winter world of ‘The Morning Before Christmas’, his whole body responds. His “every cell” is “dazzle–stamped” by the sharp beauty of his vision of the creation of a new–wrought, Golden world. He suffers, too, the “painful”, anaesthetised numbness and death which attend the birth of the “ticking egg” in ‘New Year’. Spring softens his shadow in ‘Four March Watercolours’, as it softens the contours of the world with new growth; and, tree–like, he shares “the fraternity of survival” and the “hope of new leaf” that springtime brings.

As the pulse of Nature quickens, so the poet–persona’s imaginative responses to the burgeoning world become more varied, and his link with the fish grows stronger. Looking down into the “pour of melted chocolate” (R.28) as the “snow–melt” brings the river new energy, he experiences a change in perspective, seeing his own world as if through the salmon’s “lidless eyes”. Under the expansive influence of the sun, the “refrozen dot–prints” (R.12) of the midwinter fox give way to the “stars at the river’s brim” of the romping “Jolly goblin” mink – a primitive “Black bagful of hunter’s medicine” crackling with life (R.32) – and suddenly the river swarms with fertile creatures which are “Possessed” by the uncontrollable procreative energies of the Goddess (R.34).

At first, in ‘Salmon–taking Times’, the persona stands ‘clear’ of this flood of creatures,

wisely acknowledging, and acquiescing to, the Goddess’s power: they, like “Swine / Bees and women cannot be turned”17. Later, wooed by the river’s gentler mood, he tries to share in its magic. Like a clumsy bridegroom, he crumples the river’s “gossamer bridal’veils” and destroys the delicate “membranes”: and, in so doing, he achieves a “religious moment, slightly dazzling” of creative union between his own physical and spiritual worlds. This important moment of wholeness and communion with Nature is reflected in the structure, as well as the content, of the poem. With great skill, Hughes brings together the conflicting elements of the creative act that the Celts symbolised in the half–faces of Brigantia. The tumultuous, unswerving, carnal urgings of the early lines give way to a mood of sensuous, fragile delight; the demonic power turns to tenderness; and, finally, the destruction of the protective membranes that separate one individual from another, one reality from another, leads to the moment of spiritual communion, beauty and promise that completes the poem.

The protagonist, by contrast with his own brief and clumsy communion with the Source, sees the ease with which the fishy bridegrooms play their part in Nature’s pattern. They weave their lives joyously and unquestioningly into the fabric of the world,

All singing and

Toiling together,

Wreathing their metals

Into the warp and weft of the lit water. –

‘Under the Hill of Centurions’(R.36).

Similarly, he ironically compares his own lumbering, alien presence in the river with the consummate skill of the Cormorant, which can dissolve at will into the fluid matrix and become one with the energies there (‘A Cormorant’ R.38).

Throughout the first few months of the year (a period of submerged but steady gestation and growth) the poet–persona shares the current of life in the river. By April, the “Deep labour” is almost over. Nursed by the elements, a new river, “With sinewy bulging, gluey splitting / All down its length”, resembling a snake sloughing its skin or a butterfly emerging from its pupa, tries “To rise out of the river” (R.40) and the time has come for this new–made river–spirit “to alter / And to fly”. Now, too, the poet persona resolves to “loosen” his spirit self (his “Ghost”) into the river’s elemental “water–mesh”, and to “be assumed into the womb of lymph”, where the eternal flux, “circling and flowing and hover–still”, can heal and renew him (‘Go Fishing’ R.42).

As yet, his spirit is immature, and the longed–for melding of human energies with those of the Source is fraught with the difficulties of divesting his ghostly self of its unwieldy, and often ludicrous, physical “clobber”, as the mock–heroic tale of the ‘Milesian Encounter on the Sligachan’ confirms (R.44–50). Nonetheless, there are moments of disembodiment, when the sheer power of the waters, the “superabundance of spirit”, makes the persona feel “a little bit giddy / Ghostly” and the “weird” sensations of the hunt alter his normal perception of the world.

Still, for the time being, the hero’s direct encounters with the elemental spirit of the river are brief and elusive, and it slips away from him “into the afterworld” like the loved, but lost, “dark fish”, ‘Ophelia’ (R.52). Drawn to the waters by this spirit, seduced by the honeyed, timeless, mercurial magic of the river, and immune to the literal blood–sacrifice of midge–bites that the Goddess demands (even whilst pouring over him her honeysuckled plenty), he haunts the river–bank like a “hunted ghost” from an ancient tomb (‘River Barrow’ (R.56)). Meanwhile, the cosmic dance of the Sun and Moon continues, and the elements spill their Heavenly treasure of “spirit and blood” onto the “slag of the world” (‘West Dart’ (R.58)). In this Earthly paradise of liquid light, this inverted Heaven which the elements create, the observer sees an entranced host of fish, “strangers” (R.60), who pursue their destiny with holy and selfless fervour as the river’s “sunken calendar unfurls” (R.64).

Watching the fish transfixed in the sun–dappled dawn–stillness of the summer river, the poet–persona is aware of the elemental Otherworld that they inhabit (‘Strangers’ (R.60)). Briefly, he perceives his own familiar “homebody” world as “merely” decorating their “heaven”, yet he is aware, too, of being separated from them: far from being able to share their blissful “Samadhi – worless, levitated”, his intrusion disturbs the spiritual unity, his “man–shape / Wobbles their firmament” and destroys his own vision of the “holy ones”, shrinking and refocusing his perceptions to the material dimension. The fish, however, have “got him” (‘After Moonless Midnight’ (R.62)). The magical fascination they exert holds him “deeper / With its blind invisible hands”. So, he is attuned to the waiting power in the river and sees, in the mature, over–ripe, beauty of the god–like salmon, the pathos of its sacrificial “execution and death / In the skirts of his bride”, which is part of the harvest yet to come (‘An August Salmon’ (R.64)).

At the height of summer, at the heart of the River cycle, the mellow, golden fruitfulness of the river scene is tinged with a “darkening” (‘The Vintage of River is Unending’ (R.66) ) that presages the Bacchanalian overflow of Nature’s luxuriant power. In Celtic Britain, this climax of summer was marked by the orgiastic fertility rites of Lughnasad, the August festival of the god, Lugh Lamfhada (“of the long arm”), who was smith, harper, poet, hero and sorcerer18. It was also the festival–time of pastoral gods, such as the horned god, Cocidius, of Northern Britain (related to Cernunnos), the Celtic Mercury who was “protector of herds and flocks”19, and of Pan and Dionysus.

‘Night Arrival of Seatrout’ (R.68) is Hughes’ own celebration of the August harvest festival. In it, the Goddess and her Celtic horned consort are almost palpably present, rioting through the massive richness of tossing oakwoods, surrounded by the threatening sensuality of full–blossomed herbs. In the central image of the poem, something strange, dangerous and beautiful erupts from the Underworld through the “river’s hole”, its nature–spirit identity conveyed by the confusing conflation of its description with that of the “upside–down buried heaven” of the river. Hughes’ skill, here, in evoking an entity which is imaginatively apprehended through a few vivid attributes, yet which remains undefined, is masterly, and somehow, “something” which symbolises everything enters the reader’s mind. “Dripping stars”, like a river–animal shaking off water, it “snarls, moon–mouthed and shivers”,

then, as the lobworms couple20 and Earth covertly rejoices, the image crystallises into that of a god/shaman erupting

then, as the lobworms couple20 and Earth covertly rejoices, the image crystallises into that of a god/shaman erupting

out in hard corn …

Running and leaping

With a bat in his drum.

Hughes, in this poem, enacts his own, parallel, shamanic ritual, using his poetic powers to link our imaginative and rational worlds. He stirs our senses with drumming and singing rhythms, mixing repeated heavy beats (such as those which begin the lines of the first stanza) with the emphatic rhythmical energy of words like ‘plunging’, ‘tossing’, ‘shattering’, ‘running’, and ‘leaping’. At the same time, he threads the drumming music with the sounds of alliteration, sibilance and assonance, to create an atmosphere in which we sense the combined beauty and horror of the “Honeysuckle hanging her fangs”; feel the weird and frightening disturbance of “the dark mist”, as the “oak’s mass/ Comes plunging, tossing dark antlers”; and appreciate, in the “snarls and shivers”, “stars”, “saliva” and the secret “singing”, the hissing undercurrent of devious serpentine energy which accompanies this sudden intrusion of imagination into our rational world.

Having evoked this powerful and dangerous spirit in his sequence, Hughes now brings the Sun–god, in Kingfisher form, to control it (‘The Kingfisher’ (R.70) ). In addition, he uses powerful shamanic and alchemical symbols, poetically wielding the shaman’s magical crystal and using the alchemical process of crystallisation to control the spirit–bird’s movements. So, the kingfisher vanishes from the poem “into vibrations”, only to re–appear in “a shower of prisms” with its “beak full of ingots”; and to vanish and re–appear again, a

Spark, sapphire, refracted

From beyond water ….

The capitalising of the word ‘God’ in ‘The Kingfisher’, also suggests the Heavenly, spiritual nature of its presence, as opposed to the pagan earthiness of the horned ‘god’ (uncapitalised) of the previous poem. And Hughes clearly marries Heavenly and Earthly energies together in this poem, embodying them in a creature which has a known and understandable presence in the river scene but which, nevertheless, has mythological associations (with the halcyon of Greek mythology, for example) that make it a suitable symbol of divine promise. It is important, too, that Hughes’ kingfisher, this “rainbow” of promise through which “God / Marries a pit / Of fishy mire”, is described as “an angler”, thereby confirming the symbolic importance of the fisherman figure in Hughes’ work (particularly in River), and identifying the heroic role which Hughes allots him.

In River, Hughes likens the fisherman to a Japanese Noh dancer in whose performance, spirit and mind, Heaven and Earth, are linked (‘Eighty and Still Fishing for Salmon’ (R.100)). Both execute a ‘dance’ of primitive simplicity which brings them into perfect harmony with Nature. Similarly, in old age and in art, when body and spirit “are lost” and the man seems like an “old rowan– arthritic, mossed / Indifferent to man” behind his “ritual mask”, then, he is closest to Nature. Rooted like an old rowan tree in the elemental world, he remains “loyal to inbuilt bearings, touch of weather”, and so, reaches unity with the “vacant swirl” of the cosmos.

Long before old age, however, the fisherman–persona in River achieves moments of unity in which Heaven and Earth are joined and he experiences the perfect elemental harmony of “the end” of his Journey. Such a moment is described in ‘That Morning’ (R.72) , when, at a point in the sequence when Nature’s energies have burst through the fragile membrane separating them from the rational human world, a divine apotheosis occurs: mediated by the “power of salmon”, the “golden, imperishable”, spiritual body is separated from “its doubting thought” and human beings become part of the divine energies,

alive in a river of light

Among creatures of light, creatures of light.

The slow rhythms of the poem; the dizzying image of the world “capsizing slowly” with which it begins; the “dazzle” of golden light in which the visionary experience takes place; and the biblical language in which Hughes describes the “sign”; all mark this as a moment of divine “blessing” and revelation – a moment in which selfhood and materialism are relinquished, and “we” (by the use of the plural Hughes includes us all in his vision) enter the eternal, elemental, cosmic dimension. This is a supreme religious moment of enlightenment and healing. It is the expression of mana. Significantly, the photograph which accompanies this poem, showing “a hawk–moth – on a meadow thistle” (a creature of the night caught in a glow of sunlight (R.127, note 73) ) almost exactly illustrates Hughes’ earlier symbol of mana in ‘Photostomias’: “The Peacock butterfly, pulsing / On a September thistle–top” (THCP.549). For the poet–persona, and for us, the revelatory nature of this experience lies not only in the enlightenment which takes place and in the apprehension of the divine light within each individual, but also, since no actual physical death occurs, in the promise such a ‘sign’ conveys of the spiritual rebirth this divine light may bring at the end of our mortal journey.

In ‘River’ (R.74) , the title poem of the sequence, this symbolic moment of communion and promise between Man and God is repeated in the image of the sacrificed and risen god which dominates the poem. This is the central symbol of Christianity: it is central, too, in the Norse mythology which Hughes identifies as part of his heritage, and in many mythologies and religions which are based on the natural, vegetative cycles of death and rebirth. Now, the cosmic “river of light” in which the creatures of the previous poem bathed becomes the Earthly manifestation of the sacrificed god. Embodied in the waters which issue “from heaven”, he is literally “broken” and “scattered in a million pieces” in our physical world; and his energy is blocked and restrained by human contrivance, so that, often, he hangs from our constructed dam–doors like Odin “hung by the heels” at the door of the Underworld of his mother, Earth. Literally, water will split dry tombs and will rise in floods amidst lightning that rends the veils of clouds and rain, “swallowing” up death and corruption. Then, through the physical cycles of evaporation and precipitation, it will “wash itself of all deaths”, so remaining “inviolable / Immortal”. In this, and in the “spirit brightness” of water, is the god’s promise of perpetual renewal. And the Biblical symbolism of the split tombs, the “sign in the sky”, and the “rending of veils”, conveys, too, the promise of resurrection “in a time after times” at the end of our physical and temporal world.

“So the river is a god” whose agony will bring redemption, and the horror of his sacrifice will blossom into beauty. Just as Hughes describes Leonard Baskin’s ‘Hanged Man’ as “a chrysalis, a giant larva” (WP.97) from which will emerge the symbolic Dragonfly (“the agony wholly redeemed, healed – and transformed into its opposite, by mana”), so his own sacrificed god, the river, accomplishes the same miraculous metamorphosis and transforms death into life.

Metamorphosis in dragonflies and other such creatures takes time. Between the death of the old form and the birth of the new, there lies a period of darkness and seeming chaos in which tissues dissolve and reform, and the cellular matter of the individual is, as it were, alchemically cleansed, purified and transmuted. Similarly, in the epic journey of the hero, the moment of enlightenment in which the healing power of mana suffuses his whole being does not end the story: his task, like that of the shaman, of Christ, of Job, and of other visionary prophets and epic heroes, must be completed by returning with this healing power to the darkness of the sick world to confront the evils therein.

This pattern of enlightenment followed by a return to darkness is present, too, in Nature’s cycles and in the cosmic year. Following the summer solstice, which marks the peak of the sun’s expansive influence on Earth, the energies turn inward, and the sun’s power, trapped within the cells of living organisms, nurtures the seeds of a future generation. Metaphorically, the solar divinities of many mythologies repeat this pattern, entering the darkness of the Underworld to await release and re–birth.

The epic hero of River also returns from the river of light to wade in a dark, Earthly, “tree–cavern river” (‘Last Night’ (R.76) ): but now, his awareness of evil colours all his perceptions and he seems to move through a “dying” Underworld river of “blood”, where even the fish seem evil. Now, he becomes aware of the sickness of humanity as it impinges on the river scene, recording in ‘Gulkana’ (R.78–84) , for the first time in the sequence, the “supermarket refuse, dogs, wrecked pick–ups” that mark the presence of people in the landscape. It is as if Man, like the sacrificed god, has fallen from his heavenly paradise: as if, with enlightenment, has come knowledge of good and evil. So, the Golden world which the protagonist saw in the opening poem of River, and which has so far retained its beauty and innocence for him, is changed and appears like a strange new land. Such is the transition from innocence to experience.

The Alaskan setting of ‘Gulkana’ is, indeed, strange to the protagonist (although Hughes, himself, came to know the river well). The evils that beset the Indian village – the “stagnation”, the “cultural vasectomy”, the sterility – were evils which Hughes saw encroach on this part of Alaska (Letters.734–6) but they are evils which are common to human societies, as Remains of Elmet has eloquently shown. Now, in River, even in the familiar English river of ‘October Salmon’ (R.110–114), the protagonist sees the tragic beauty of the salmon set amidst “bicycle wheels, car–tyres, bottles / And sunk sheets of corrugated iron” and all the debris of human profligacy and waste. He sees, too, the alienation and cruelty of the children.

Nevertheless, the Gulkana has a special place in the hero’s epic journey, for it is the river in which he enters the terrifying bardo–state of illusion; a state described in sacred Buddhist texts as that which follows the experience of ‘luminosity’ and in which are encountered demons which are projections of the human mind21. Prompted by the undercurrent of archaic power in the Gulkana, the protagonist begins to recognise something within himself that he “kept trying to deny”. Slowly, linking sensation and thought, imagination and rationality, he comes to acknowledge the duality within him, explaining the nagging “illusion” which dogs his steps, by personifying it as his daemon:

– one inside me,

A bodiless twin, some disinherited being

And doppelganger other, unliving,

Everliving, a larva from prehistory

Whose journey this was,

Whose gaze I could feel,… – ‘Gulkana’ (R.80).

This terrifying projection is of the wild, untamed part of himself that he constantly rejects and fears; and now he imagines its barely suppressed power as the jealous hatred of a ghostly double. Significantly, the protagonist confronts his inner self in the ethereal, alchemical and spiritual brilliance of “mercury light” (a light which is beautifully captured in the photograph on page 85), but the experience still fills him with “lucid panic”. Wading a strange river, in a landscape which seems to shift and subside “in perpetual seismic tremor”, he turns, as he has before, to the salmon, seeking their wisdom and guidance. But they, too, seem “possessed / By the voice of the river / By its drums and flutes of its volume”, and in their eyes he no longer sees the divine spark, the scintilla of hope and renewal, but something “small, crazed, snake–like”, something chilling and remote like “a dwarf sunken sun”. The only certainties in this place are death and dissolution. This is the “revelation”, the “burden”, that the poet–persona records, “word by word“, when he re–awakens in his own familiar world of noise, machines and “incomprehension”.

Following ‘Gulkana’, Hughes exerts all his musical and poetic skill to heal the fragmentation which has occurred. The poem, ‘In the Dark Violin of the Valley’ (R.86) , fills the valley “grave” with magical music, and its vibrations and its flow re–connect the disparate elements of the world as if sewing them together. The imagery recalls that of ‘Spring–Dusk’ in Remains of Elmet (ROE.66) , where the drumming “witchdoctor” snipe use the “new / Needle of moon” to sew Heaven and Earth together. Now, it is the movements of a disembodied violinist that suggest a suturing surgeon: with the bow as his needle, and the music as his uniting thread, he probes, penetrates and heals the body of Earth. The reader, also, is soothed, and emotions which were disturbed by the disruptive energies of ‘Gulkana’ are drawn, by the smooth, compelling movement of Hughes’ lines, into a newly created atmosphere of harmoniously balanced tensions.

Despite the healing music, Hughes’ poet–persona still journeys through a strangely altered world. No longer is he naively enthralled by the rich honeyed mystery of the river as he was in ‘River Barrow’: instead, he sees the intemperate, voluptuousness of the Goddess, who entices him to “Copulation and death” (‘Low Water’ (R.88)). No longer is the Cormorant admired as a “deep sea diver“, expertly “Dissolving himself / Into fish, so dissolving fish naturally / Into himself” (‘A Cormorant’ (R.38)): now, it is ‘A Rival’ (R.90), a “dinosaur massacre machine”, “cancer in the lymph, uncontrollable”, “An abortion doctor” violating the pool and leaving it “mutilated, / – Dumb and ruined”.

The threatening atmosphere of decadence and evil, which the persona feels all around him, is matched by the decaying summer richness of the natural world as the Earth moves toward the Autumn equinox and night and day become of equal duration. The sun’s power is at low ebb, “The fuel / Nearly all gone” (R.92), and darkness begins to engulf it (the photograph on page 89 is richly evocative of this). By “Michaelmas” (‘August Evening’ (R.92–94)), the “biological blaze” of the “August burn–out” (R.88) has “charred” the day–time world to a scene of cooling skeletal brittleness: and presently, the moon, “crisp” and new, begins to work its eerie magic.

The Michaelmas festival, which the “sea–tribes” of Hughes’ poem (both fish and human) celebrate, is a Christian festival dedicated to the archangel Michael, who cast the Devil out of Heaven. The atmosphere which the protagonist describes in ‘August Evening’, however, is both religious and pagan. The influence of the moon and of the “terrible” powers of darkness (always especially feared by the Celts at the equinoxes when light and darkness struggle, as it seems, for supremacy) pervade the poem, but balancing their energies is the “religious purpose” of the fish, who forgo the “carnival” to “cobble the long pod of winter” that holds the seeds of future life. The spirit which inspires them, and which briefly creates the “white pathway” on which they and the protagonist (“I share it a little”) are held in the “stilled flow” of the “unending” creative energies, is as much that of the pagan psychopomp, Lugh/Mercury, who dominated the Celtic harvest festivals at this time of year, as that of the Christian, Michael, who replaced him. This is suggested, too, in the photograph on page 93, where the mercurial glow of the sun just penetrates the mist above the blackened, eerie land, enhancing the imagery, atmosphere and meaning of this poem.

The same solar and alchemical “mercurial light” (R.98) illuminates the creatures in the poems that immediately follow ‘August Evening’. In ‘Last Act’ (R.96) which is “performed by a male”, although the Damselfly is female, it lights the “miracle–play” of love and death, from which she emerges “dripping the sun’s incandescence”22. And it lights the god–like “homage” and sacrifice of the ‘September Salmon’ (R.98), heroically and “Famously home from sea”23 to become “a god / A tree of sexual death, sacred with lichens” and to add his creative “daub” “To the molten palate” of transmuting energies captured in the river.

As the winter approaches and the poet–persona’s world moves further into darkness, he becomes more conscious of the imminence of death and the subsequent return to an elemental state. He sees it in the mating of the Damselfly and in the purposeful gathering of sea–trout; and he sees it in the indifference and remoteness of the ancient fisherman (R.100). At the same time, he is aware of a deep undercurrent of life in the river, and this duality is expressed in the paradoxical character of the river in ‘September’ (R.102) and in the double nature of the eel (‘An Eel‘ (R.104)) a primitive creature which knows, and regularly returns to, its source.

The hermaphrodite eel, in its duality, its knowledge, and its cyclical journeying around the Earth to the spawning grounds of the Sargasso, strongly evokes the image of the cosmic snake, Uroborus. Duality and knowledge is suggested, too, by calling it “the nun of water”: which suits its “love”, its “patience”, and its annual pilgrimage to the source of its existence. ‘Nun (the fish)’, is also the fourteenth letter in the Hebrew alphabet, where it is seen as “the faithful one” – a vessel of the divine, selflessly linking heaven and earth. And ‘nun’ also invokes the Ancient Egyptian deity, Nun (Nu), symbol of chaos and the primordial ocean, and source of “all things and all beings”24.

So, the promise of renewal persists until, in ‘Fairy Flood’ (R.106) , the cosmic snake becomes the river itself, the “earth–serpent with all its hoards, casting the land, like an old skin”25. Like the Egyptian Nun’s flood waters bringing the annual return of chaos to the Nile Valley, the fairy flood carries everything “towards the sea”. The land “crumbles” and “melts” into emptiness, and the river’s “jubilant” energies break chaotically free.

Surrounded by such dark and riotous energies, the poet–persona (the ‘Riverwatcher’ (R.108) of the poem’s title) feels in danger of being swept along, like “a holy fool”, by the ecstatic allurements he glimpses. To protect himself, to keep his “head clear / Of the river–fetch”, he utters a prayer – a poetic charm – willing himself to concentrate and to cling “With dry difficulty” to whatever shreds of reality he can find. The immersion he fears is that of ecstatic self–absorption, such as the “Bismillah”–inspired dancer enjoys. As with the false heavens of ecstasy offered by the ‘Green Mother’ in Cave Birds (CB.40), succumbing to this temptation would entail forgoing the selfless spiritual task and accepting, instead, perpetual existence in the self–serving, vegetative cycles of regeneration. Such a choice would involve a negation of the rational mind in favour of the spirit and soul: a choice which would perpetuate the divisions in human nature rather than heal them.

Like the ‘October Salmon’ (R.110–114), the protagonist survives the flood. Looking, now, at this fellow creature with which he so strongly empathises, he sees the pathos of its “death–patched” beauty, and

The epic poise

That holds him so steady in his wounds, so loyal to his doom, so patient

In the machinery of heaven.

Watching the salmon, he is filled with the wonder and love which is expressed in this poem; and he perceives, also, the divine order in Nature. Like the “intricate and sinister pattern” (R.128: Note 115) of the dewy spider’s web on page 115, the cosmic web links everything together and everything to its source: the wonder and the horror are ever present, “inscribed” there, as it were, from the very beginning. “That is how it is”26 (R.112) : and, as the poet–persona understands and acknowledges this, there comes acceptance of his own place in the pattern.

The regenerative cycle of the river is now almost complete.

Like entwined Uroboric serpents, the “river’s twists” in ‘Visitation’ (R.116) ) bite “each other’s tails”, and a star (the heavenly sign of guidance and hope) “fleetingly” illuminates the presence of a “dark other”, whose “visitation” brings a new creature out of the river. Like (yet also unlike) the river which bears it, this creature emerges in a new and extraordinary dawn, leaving the signs of its presence in the Earth–mud. It is, at once, a living river–creature and an eerie “flower” of promise from the Tree of Life.

A suggestion of the conception, annunciation and birth of the Holy Child underlies the symbolism of ’Visitation‘, but Hughes grounds events firmly in the world of Nature. The presence of the river; the ghost of his Otter (THCP.79) whistling and crying through the poem and leaving its “pad–clusters” in the river mud; as well as the frost–etched star–cluster of the winter cow–parsley, which lights the darkness on the page opposite the poem (R.117); all forcefully evoke the natural setting, so that the star’s promise encompasses, and is demonstrated through, the world of Nature.

Not only does ‘Visitation’ again express Hughes’ concurrence with Blake that “everything that lives is Holy” (MHH.27:chorus), it also embodies his belief that mana is manifested in all created objects and, especially, in the works of Nature. Hughes seeks to illustrate this in his own poetic creation by using natural imagery, which imaginatively merges spirit with matter, symbolism with reality, and Heaven with Earth. He also entwines his images in such a way that the ‘dark other’, the stars, the strange river–creature and the Tree of Life, are almost indistinguishable from the river itself. Thus, he mimics the inter–relation and flux of the cosmic energies, and achieves, through his poem, a glimpse of unity and continuance, wherein lies hope.

In ‘Torridge‘ (R.118), Hughes continues to draw the threads of his world together. The cosmic year is nearly over, the river’s annual cycle almost complete; and, as Nature’s energies move towards their lowest winter ebb, Hughes begins a poetic reconciliation of contraries which will unify the disparate elements of his sequence, connect them with the cosmic Source, and complete the pattern. Flowers of “garlic” and “iris” (both species associated with the Goddess, the moon and death) are linked with the “heron” which (as in ‘Whiteness’ R.20) symbolises the risen Sun–god and the regeneration of life and light. The growth, pollination, withering and death of these flowers trace the annual seasonal pattern. “Venus and Jupiter”, “morning star” and “evening star”, fish souls and fish bodies, Adam and Eve, April and December – all these fit into the pattern, but such apparently contrary states and separate identities are peripheral to the “stillness” and constancy of the Source from which they come. Seemingly different, these elements are all connected like the strands of the cosmic web, or like the pictured “ice crystals and miniature chasms” made “At the water’s edge … as freezing and thawing alternate” (R.128:Note 119). Each is part of the universal and everlasting flux of energies that Hughes symbolises in the river.

The final poem of the River sequence, ‘Salmon Eggs’ (R.120–124) , is, as usual, of special importance. It is Hughes’ “liturgy / Of the earth’s tidings” his final, clear statement of the presence on Earth of mana, the divine, ‘nameless’, ineffable Source. In it we hear, as we heard earlier, the music of the river – the throb of “the aorta” (R.86) that carries the spirit and blood of Earth endlessly. Now, the music is like the “toilings of psalm” that accompany holy communion with the Source of all. And in a letter to Ben Sonnenberg, Hughes spelt out the presiding image of the poem as that of Sheila–na–gig – “literally Woman Of the Tits”…. “our oldest goddess (a death/battle/love goddess) who copulated with her consort standing astride rivers (I suppose, where she also gave birth). (A suggested scholarly correction makes her Sheila–na–gog – woman of god, God’s Wife. Gog in old Irish means God!)”, (Letters.448).

Repeating the pattern of Cave Birds and Remains of Elmet, this final poem marks both an end and a beginning. We have reached the end of a year in the river’s life, and the end of a poetic sequence. The poet–persona, too, has reached the end of his epic journey: he has heard Earth’s tidings, and his understanding of the presence of mana in Nature is demonstrated in this final poem. Yet, these endings are no more than a still point in “the nameless / Teeming inside atoms – and inside the haze / And inside the sun and inside the earth”: from this stillness new growth will come, because the river “is the font, brimming with touch and whisper / Swaddling the eggs” which now rest in the endless flow of its waters.

In its winter dormancy, the Earth itself is egg–like, resting in the albuminous “haze” of its atmosphere and nurtured by a “veined yolk of sun”. Its quiescence is reflected in the meditative mood of the poet-persona, and in the long reflective lines of the poem’s opening stanzas, their frequent vowel sounds, pauses and repetitions:

The salmon were just down there

Shuddering together, touching each other,

Emptying themselves for each other

Now beneath flood–murmur

They curve away deathwards.

January haze,

With a veined yolk of sun. In bone–damp cold

I lean and watch the water, listening to water…

In the numbing cold, the protagonist’s mind fills with images of spawning salmon in sacrificial ecstasy; and his senses expand to the sights and sounds of the river, until he loses self–awareness and “the piled flow supplants” him. His perceptions cleansed, as it were, by this flow, his imagination “blooms” like the river “mud”, to show him the “ponderous” and “everlasting” flux of energies at work in the “sliding” river. He is aware, all around him, of the “minute particulars” (MHH.14:17–19) of Nature – the wriggling catkins and the careful spider – but he sees, too, the infinite and the sacred elements of the “perfect whole”.

The wholeness of Hughes’ vision is embedded in the language of this poem, where the essence of these waters which unite life and death, temporal and eternal, sacred and profane, is compressed into oxymorons like “Mastodon ephemera” (which combines nurture and destruction: ‘mastos’ = ‘breast’; ‘odous’, ‘odontos’ = ‘tooth’) ; “ponderous light”; “Mud–curdling, bull–dozing”; “exhumations and delirious advents”; “More vital than death … / … More grave than life”; “burst crypts”; “harrowing, crowned”. There is constant punning, too, by means of which physical and metaphysical concepts are linked. The phrase ‘ponderous light’, for example, conveys the weight and the brightness of the river water, and also connotes weight, thought, mind, light and enlightenment. The inter–relationship between physical reality and the metaphysical, which such punning embodies, is the fundamental message of Hughes’ work: and it is summed up in the closing line of the River sequence, where “mind condenses on old haws”, like the “dew that condensed of the breath of the Word” (THCP 35) at the moment of creation. Illustrating this message is Peter Keen’s photograph of lit dew on a single hawthorn fruit, which is centrally placed in the pages of final poem. Not only is it a magnificent picture of condensed light, but it also reflects the wholeness which both Hughes and his protagonist have achieved. In it, life–giving light and water swathe a plump fruit of the hawthorn, which is sacred to the Goddess, thus joining her Lunar energies with those of the Sun, and uniting Earth and Heaven, Nature and Spirit, darkness and light, death and birth. Above all, at the conclusion of this river epic, the inner and outer worlds of Mankind are reconciled, Earth’s tidings are heeded, and the protagonist’s mind ‘condenses’ its knowledge by turning Earthwards to the fruits of Nature.

As a fitting conclusion to the River sequence, Keen’s photograph (R.125) of the unscarred serenity of the River Exe (R.128: Note 125) beautifully demonstrates that people can work in harmony with Nature, and the lit pathway of its waters leads the imagination hopefully forward into an unknown world.

ADDENDUM: Bringing the book to life.

River was a long time in the making. In a document in the British Library, Peter Keen describes the seed of the book as being sown in 1976 when, at Carol Hughes’ suggestion, he and Ted first met in Devon to go fishing together. The two men discovered that they shared a mutual understanding of the sport and this became the beginning of a long–term friendship. Some time later, Peter Keen wrote to Ted suggesting that they collaborate on a book about rivers and the associated wildlife and Ted, after seeing some of Peter’s photography, liked the idea and agreed. As Peter remembered it, they were to be co–authors, each making their own separate contribution: Ted not reflecting Peter’s photography and Peter not illustrating Ted’s work.

In April 1978, Olwyn Hughes, acting as their agent, began negotiations with the publishers David & Charles. The intention was to produce “a really handsome book, a kind of collector’s piece” with possibly a small, signed edition alongside a normal trade edition. By July, there was talk of Ted and Peter producing enough text and pictures to create a dummy book to show at the Frankfurt Book Fair later that year.

By August, negotiations with David & Charles had stalled over a dispute about the handling of American rights, and the possibility of Faber taking on the book was raised.

From 1979 until September 1982, negotiations with various publishers continued, the main difficulty being the cost of producing a beautiful book with first–class paper and the best colour reproductions. Meanwhile, Ted was writing poems but Peter was slow in providing Olwyn with photographs to show to the publishers.

In early July 1979, it was suggested that River poems and photographs might be included in an exhibition of Ted’s illustrated work to be held at the Victoria & Albert Museum in London in September/October. Just two photographs by Peter Keen were included in the exhibition, ‘Sea Trout Rising’ and ‘Trout Reflection’, together with a note that they were for a projected book of poems and photographs provisionally called ‘River‘.

That same year, the idea had been floated that Nicholas Hughes should create a dummy book, with prints, on his newly acquired Albion press. However, it was not until 1981 that he produced limited editions broadsheets of three of Ted’s River poems: ‘Catadrome’, ‘Caddis’ and ‘Visitation’, each illustrated with drawings by Ted.

By April 1980, Ted was writing to Keith Sagar that the text for the book was “finished more of less” (Sagar,K. Poet & Critic, British Library, p.91), although he later wrote that the River poems were “still oozing along” (P&C.113); and in October 1982 he was still “writing and rewriting them” (P&C.120).

By May 1981, James McGibbon, who had been handling negotiation at David & Charles but had since moved to the publishers, James & James, had picked out twenty–one photographs from which transparencies had been made and a dummy book has been sent to several publishers. One had also been sent to Shell and the British Gas Company with a view to obtaining sponsorship from them. The initial response from Shell was based on the idea that the book might be a subtle way for them to demonstrate their concern for the environment. They suggested that they would require 2–3 pictures clearly demonstrating this, and that the title must be The Shell Book of the River. They also wanted a children’s poetry competition linked to the book, and a special edition for school libraries. What they really wanted, as McGibbon noted, was prestige and a clear commercial image.

By September 1981, Faber were talking about a trade edition of the book with just a few pictures. The Observer, on the other hand, had expressed an interest in producing “a splurge edition” with magnificent photographs and “simply text”. As Ted described it to Keith Sagar (P&C.95), it was to be “Not a coffee table book, but an ambassador’s gift. Hugely expensive” – a book in which “nobody, who’s going to buy the book, is going to read my verses. They could as well be Middle–Kingdom curses, in the original. They’re just decorated with a respectable aura”.

The Observer book did not eventuate but by January 1982 Faber were expressing real interest, provided a sponsor could be found; and by September that year agreement had been reached with the British Gas Corporation and a joint publication by Faber & Faber and James & James had been decided. British Gas was to select the cover photograph and to add a note making a point about their re–landscaping following the installation of underground gas pipes. They also stipulated that the book should not be more expensive than the market was used to.

The contract which was drawn up with Faber divided royalties in their customary manner for illustrated books: 75% for the text, 25% for the photographs.