“…Before these chimneys can flower again / They must fall into the only future, into earth” (ROE.14)

Imagination, for Hughes as for Blake, is the one thing which may save humanity from self–destruction. So, in Remains of Elmet, he uses his imagination and skill to evoke a world which is both realistic and symbolic; and, through his poetry, he imaginatively engages the reader in the changes which have affected the Calder Valley society and which both demonstrate and symbolise its fallen state. Similarly, he evokes the natural energies which oppose destructive human endeavours and which work to redress the delicate balance that people have disturbed.

In ‘Lumb Chimneys’ (ROE.14), for example, Hughes’ choice of plants, and the similes with which he couples them, realistically suggest the release of Nature’s suppressed power in an ecologically and socially disturbed environment. Nettles and brambles, and “depraved” sycamore, are in the van of Nature’s army: they are the weeds against which we fight an eternal war in our attempt to control our environment, and they epitomise Nature’s fecund power, its capacity for using, “like the cynical old woman in the food–queue”, every possible means of survival. So, in ‘Lumb Chimneys’, “the nettle venoms into place”

The bramble grabs for the air

Like a baby burrowing into the breast.

And the sycamore, cut through at the neck,

Grows five or six heads, depraved with life.

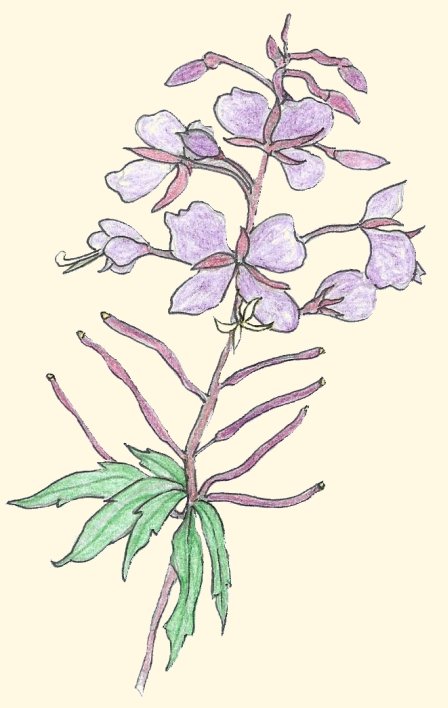

And elsewhere in Elmet, “Vandal plumes of willow-herb”, that “Mauve–pink flower” which thrives in rubble and destruction, invade “desecrated mounds” (ROE.79,73).

The echoes of a passage from Blake’s Milton, in which he describes the dance “Around the Wine–presses of Luvah”– the orgy of natural energies which accompanies this “War on Earth” – are very strong:

There is the Nettle that stings with soft down, and there.

The indignant Thistle whose bitterness is bred in his milk,

Who feeds on contempt of his neighbour: there all the idle Weeds

That creep around the obscure places shew their various limbs

Naked in all their beauty dancing round the Wine–presses,

But in the Wine–presses the Human grapes sing not nor dance: (Mil.29:8–29)

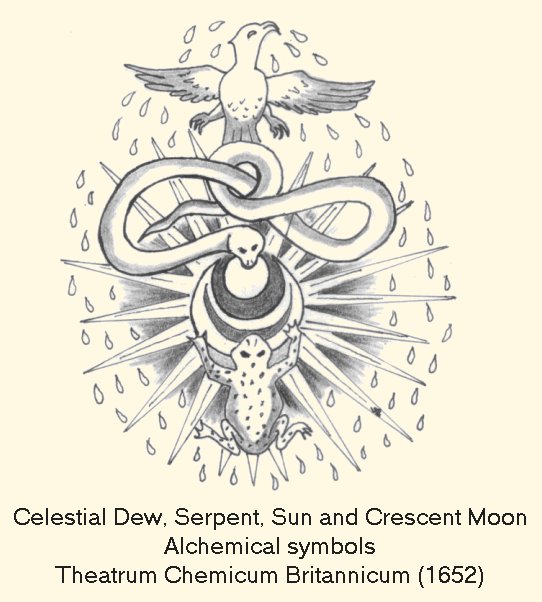

Both poets imaginatively and symbolically celebrate the supremacy of the natural energies, but, for Hughes, Nature is not so much rejoicing at Man’s downfall, as performing a necessary and inevitable revolutionary function: and in the final lines of ‘Lumb Chimneys’ Hughes shows such a natural revolution to be our “only future”. In this poem, society, its spirit and its achievements, fall literally and figuratively “into earth”, from which they may “flower again”. As in an alchemical synthesis, the people of Elmet must undergo death, disintegration and purification in the crucible of Earth before renewal can occur.

The dual capacity of Nature for destruction and recreation – the cycles of death and rebirth – are of central importance in Remains of Elmet, as they were in Cave Birds, Gaudete, and most of Hughes’ other work. Now, however, they are related more closely and more consistently than ever before to the reality of the natural forces as experienced in a specific location. Earlier poems, such as ‘Pennines in April’ (THCP.68)1, ‘Mayday on Holderness’ (THCP.60) and ‘Heptonstall’ (THCP.165), presage such illustrative use of Hughes’ native landscape. The characteristic release from earthbound naturalistic description into soaring imaginative flight can be found in Hughes’ poetry from ‘Hawk in the Rain’ (THCP.19) onwards, but in Remains of Elmet these features are combined in a sustained and deliberate exploration and exploitation of Nature’s cycles. Paradoxically, the immediacy and veracity of Hughes’ descriptions are such that many readers respond to their forceful reality and miss the unifying symbolism which discloses the hidden presence of the Goddess. Similarly, the nostalgia and empathy the poetry arouses in readers who sorrow for times past, a changing world, and lost loved ones, may blind them to Hughes’ deeper purpose.

It is possible, too, that the connection between the finite and the infinite, phenomena and noumena, is now so inseparable in Hughes’ own perception of the world that he simply fails to make a clear distinction between them in the Elmet poems. Yet, to accept this view would be to ignore the meticulous care with which Hughes habitually constructs his poetry, and his constant striving towards the reunion of our inner and outer worlds. It is more consistent with Hughes’ methods, ideas and purpose to regard his vivid realism in Remains of Elmet as deliberate: a means by which he seeks to stimulate the readers’ imagination, involve them emotionally in this envisioned world and, thereby, create in them an awareness which may awaken them to their own errors and illusions. In the wild landscapes of the Elmet poems, Hughes re–creates the encounter between “the elemental things and the living, preferably the human” which he believes stirs up “ancient instincts and feelings” that are “like a blood transfusion to us” (PIM.77–8). Thus, he exposes us to the “Healing and sweetening” (ROE.114) powers which he evokes and uses his poetry as a “biological healing process”, in terms of which he once described it2.

All this is consistent with the magical/ shamanic/alchemical potential which Hughes ascribes to poetry; its power to change what is depressing and destructive into something healing and energising; its power, ultimately, to change the reader and the poet, because

Poetry is not made out of thought or casual fancies. It is made out of experiences which change our bodies, and spirits, whether momentarily or for good.(PIM.32)

Through his poetic depictions of the moods of Nature and the force of the elements; by harnessing the transforming power of the unnaturally clear light of the moors which pervades the poems and photographs; and, especially, through his own love for this land and its people, which shines through so many of these poems, Hughes attempts a transformation akin to an alchemical synthesis, by means of which both Elmet and the reader may be enlightened and renewed.

Whatever the nature of Hughes’ poetic purpose, in Remains of Elmet he re–creates a world where, from very early childhood, he was aware of threatening divisions both in and around him. In The Rock, a BBC broadcast, the text of which was published in The Listener (19 Sept.1963. pp.421–3), Hughes spoke of the strong shaping influence of his early environment: “The most impressive early companion of my childhood”, he said, “was a dark cliff”. Always aware of this overshadowing presence, he sought escape on the moors around his valley home:

The rock asserted itself, tried to pin you down, policed and gloomed. But you could escape it, climb past it and above it, with some effort. You could not escape the moors. They did not impose themselves; they simply surrounded and waited....

And just as the outlook of a bottle floating upright at sea consists of simple light and dark, the light above, the dark below, the two divided by a clear waterline, so my outlook was ruled by simple light and dark, heaven above and earth below, divided by the undulating line of the moor...

[There] the visible horizon was the magic circle, excluding and enclosing, into which our existence had been conjured, and everything in me seemed to gravitate towards it.

Clearly, the division between valley and moor, darkness and light, which is so evident in the Elmet sequence, was part of Hughes’ earliest experience. So, too, were other more fundamental divisions, for the moors gave Hughes a different perspective, exposing objects in an “unnaturally clear” (The Rock) light and making him aware of another, vaster dimension. The disparity between the world of the moors and life in the valley was such that

From there (the moors) the return home was a descent into the pit, and after each visit I must have returned less and less of myself to the valley. This was where the division of body and soul began.

In Remains of Elmet, Hughes generalises this personal experience of a division between body and soul (the division between the exhilarating world of Nature where spirit and imagination are free, and the mundane, pragmatic, materialistic world of the valley) to explain the divisions which he describes in the whole Calder Valley society: divisions which he also attributes to society in general. The parallel, here, with the Porphyrian concept of the immersion of spiritual light in the world of Generation is very strong. Similarly, the impulse which had always driven Hughes towards the moors and Nature (physically and imaginatively) may well be recognised as the struggle of light within him for its own release.

So, Hughes turned to Nature’s healing powers to mend this division. And one of the clearest indications of the way he viewed these powers is found in ‘These Grasses of Light’ (ROE.16), where the four alchemical elements – fire, earth, water and air, embodied in the grass, the stones, the watery light and the wind of our Earth – are seen as the protective “armour” of the metamorphosing human soul.

The sparse clarity of the poem’s lines and images reflects the starkness of the silhouetted trees against the wash of light and darkness in the facing photograph. The small details of the scene, created by the interplay of light and shadow fixed in the photographic image, are at once the individual elements of the picture and of the pictured scene, as well as “the world” (both real and imaged) which together they create. The “grasses” of light, the “stones” of darkness, the faint suggestion of wind bending the reeds around the lonely seated figure in Fay Godwin’s photograph, are not just isolated elements of some larger group which wait for the imagination to unite them and give them meaning:

Are not

A poor family huddled at a poor gleam

Or words in any phrase

Or wolf–beings in a hungry waiting

Or neighbours in a constellation

They are the essential mother elements of creation from which the world is formed; the seemingly trivial “bric–á–brac” on which we must rely for our survival; small intimations of a universal power far greater than our imagination can encompass. Like the phenomena of Nature which, for Blake, were the “Children of Los”, these, too, are

the Visions of Eternity;

But we see only, as it were, the hem of their garments

When with our vegetable eyes we view these wondrous Visions. (Mil.28:10v12).

Through imagination we may glimpse the infinite, although we see only the finite details of the natural world: so, small details make up a picture or a poem which may stimulate our imagination and stir our emotions, thus uniting our inner and outer worlds.

The photograph which accompanies ‘These Grasses of Light’ and ‘Open to Huge Light’ has considerable emotional impact, and this is enhanced by Hughes’ images, which suggest the near extinction of the light by darkness, and which fill the emptiness with the “music” of desolation; but ‘These Grasses of Light’ requires a rational rather than an emotional response to appreciate the complexity of its layered meanings.

Such rational complexity is common in Hughes’ poetry. But, in Remains of Elmet, poems where the intricacies of meaning hold sway are balanced by others in which the emotions predominate, so that again Hughes is seen to be working towards integration and wholeness.

Balance is aimed for, too, in the positioning of the poems, so that the exhilarating and the numinous qualities of Nature counteract the sadness and despair aroused by Hughes’ pictures of a disintegrating society. This particular kind of balance was discussed by Hughes in reference to his Moortown Elegies, published in a limited edition a few months before Remains of Elmet. In a taped reading of some of those poems Hughes talked of the emotional impact of poetry and of his

superstition that the writer, even more than the reader, is affected by the mood and the final resolution of his poem in a final way. [For] In each poem, the writer to some extent finds and fixes an image of his own imagination at that moment. But if a poem concludes in a downbeat mood his imagination is to some degree fixed and confirmed in that mood. In the ordinary way his imagination would heal itself – move on to new moods, but the poem stands there, permanent, vivid and powerful and tries to make him continue to live in its image3.

To combat this ‘downbeat’ effect, Hughes deliberately set out to write poems “whose whole accent” is upbeat. So, in the Elmet sequence, a particularly downbeat poem like ‘Remains of Elmet’ (ROE.53) is followed by one full of exhilaration, movement and hope – ‘There come Days to The Hills’ (ROE.54). In this poem, as our perspective changes from the dark valley to the freedom of the moors, nature is metaphorically freed from the ugly remains of Man’s endeavours and the whole mood lightens. The next poem in the sequence, ‘Dead Farms, Dead Leaves’ (ROE.55), continues the change of perspective by placing the world (like the World Tree of mythology, which the imagery of the first two stanzas suggest) in a cosmic framework: dead farms and leaves “ cling to the long / Branch of the world;” and

Stars sway the tree

Whose roots

Tighten on an atom.

Within this broader framework, the birds, “the cattle of heaven”, move symbolically and with magical ease between known and unknown worlds as they

Visit

And vanish.

Like the birds and animals in Hughes’ earlier poetry, those in Remains of Elmet are symbols of natural energy. They are common, realistically portrayed denizens of the Calder Valley landscape, but they are, also, imaginative keys with which Hughes, like Blake, attempts to unlock our “single vision” and open our senses to the “immense world of delight” (MHH.7E:4) in and around us. He uses them to draw us imaginatively into the elemental realm of the Goddess, but their appearances in this poetic sequence are few, and their role as shamanic guides or emissaries of the spiritual world is not of central importance, as it was in Cave Birds. Instead, they provide links with the Universal Energies, channelling imaginative life and beauty into the sequence at times when it is most necessary, or evincing the continuing existence of such energies in the midst of desolation and decay.

Sometimes the animals are victims of the decay, enduring, like the sheep, enforced participation in human endeavours. Yet, although the “few crazed sheep” (ROE.30) that survive the ‘shipwreck’ of this society are bedraggled, maggot–ridden, wormy and ‘The Sluttiest Sheep In England’ (ROE.104), still their eyes reflect the powerful energies of Nature from within and around them. The elemental “witch–brew boiling in the sky–vat” of the moors “Spins electric terrors / In the eyes of sheep” (ROE.19), and the gaze of “their demonic agates” can, like that of the “square–pupilled yellow–eyed”, “black devil” goat in the early poem ‘Meeting’ (THCP.35), stir the imagination, disturb our equanimity, and remind us of our true insignificance in the vast compass of the Universal Energies.

In ‘The Sluttiest Sheep in England’, these bedraggled angelic “beggars” sent by the “god–of–what–nobody–wants”, the god of “This lightning–broken huddle of summits” which is our Earth, remind us of our ancestry as they

clatter

Over worthless moraines, tossing

Their ancient Briton draggle–tassel sheepskins

Or pose, in the rain–smoke, like warriors –

They serve, like Hughes’ tramps, to demonstrate the primitive strengths we have lost through our war with Nature.

The role of the sheep as the Earth–god’s angels, and the pervasive imagery describing their watching ‘demonic’ eyes, suggests the presence of some great implacable power which, through them, observes our steady progress towards self–destruction, biding its time before appearing. A possible resolution to this waiting is given in the next poem in the sequence, ‘Auction’ (ROE.107), where Hughes shows a society so alienated from nature that even the farmers are as “rotten and shattered” as their possessions. In such a society there can be little hope. Yet, with “Wind pressing the whole scene towards ice”, they wait for a goat – the symbol of nature’s fertile energies; the form of Pan, the son of Hermes/Mercury and the god of shepherds; and the one creature which might survive in this barren land and bring new life to the area. The ambiguity of the final line of the poem allows for the awaited emergence of Pan from the Underworld ’ Pan

whom Nietzsche, first in the depths, mistook for Dionysus, the vital, somewhat terrible spirit of natural life, which is new in every second4.

At the same time, Hughes’ final line describes a realistic auction situation.

Unlike the sheep, the birds in Remains of Elmet rarely share the lives of men. Because they are not earthbound, but move with ease between Heaven and Earth, Hughes consistently uses them to link the physical with the metaphysical. He chooses birds which are common on the Yorkshire moors, and which have folkloric connections with the spiritual world as well as mythological significance. In particular, Hughes’ curlews and snipe play significant roles in returning the fertility of the Goddess to a plundered and ravaged Earth, and punctuating the dark atmosphere of the poetic sequence with shafts of light and beauty.

Following a series of poems in which Hughes describes the entrapment, enfeeblement and degradation of energy and spirit in warfare and materialism, come the two poems, ‘Curlews in April’ (ROE.28) and ‘Curlews Lift’ (ROE.29), in both of which the natural beauty of the world predominates.

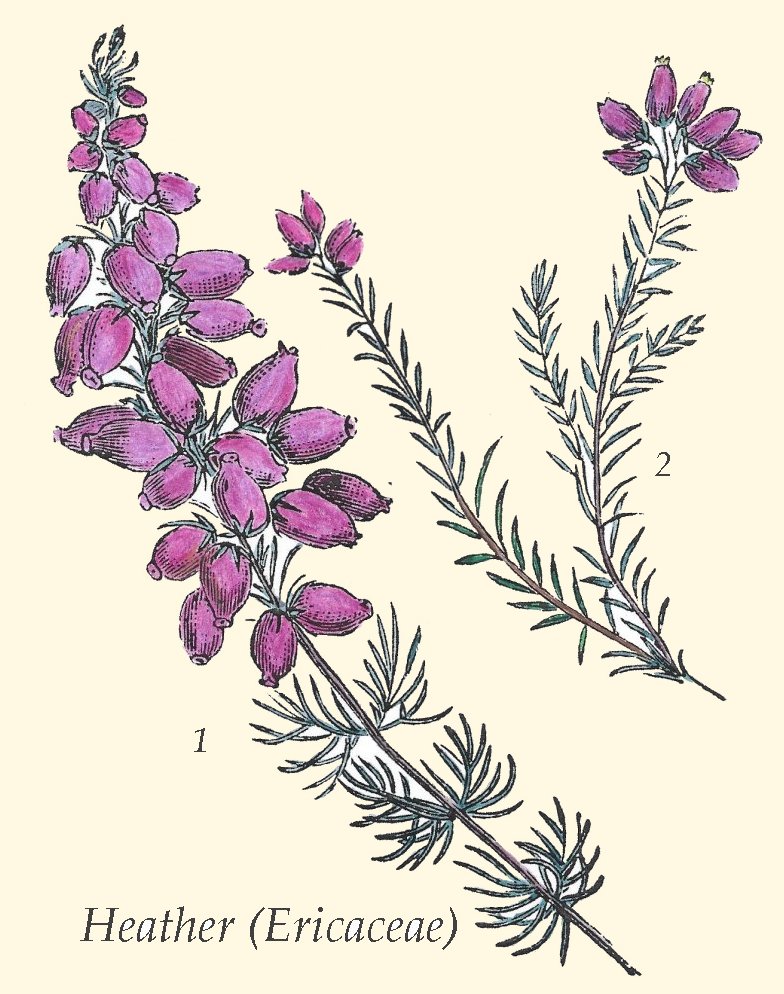

The first of these poems takes up the final, grievous, image of ‘Long Screams’ (ROE.6), and the cry of the curlew, the “moist voice” in which Hughes once identified the “peculiar sad desolate spirit” of the moors (The Rock), becomes magical harping over the misty valley. The curlew’s strange nocturnal cries have led to widespread folkloric associations of it with Gabriel Hounds and the souls of the dead5, but it is also a fertility symbol. In Hughes’ poems, both these aspects of his “wet–footed god of horizons” are present. In April, the month of springtime and renewal, its “wobbling water–call” conjures the moon: “new moons sink into the heather” and rise from it “full golden” and bulging. The sexual connotations are implicit and are reinforced by the procreative connotations, luxurious sound and active tense of “bulge” (the word is also emphasised by its typographical separation from “full golden moons”). This, together with the impression of temporal contiguity, which is given by coupling the two events in linked lines, suggests the magical fecundity of the moon, which rises from the Earth radiant with the promise of new life.

The first of these poems takes up the final, grievous, image of ‘Long Screams’ (ROE.6), and the cry of the curlew, the “moist voice” in which Hughes once identified the “peculiar sad desolate spirit” of the moors (The Rock), becomes magical harping over the misty valley. The curlew’s strange nocturnal cries have led to widespread folkloric associations of it with Gabriel Hounds and the souls of the dead5, but it is also a fertility symbol. In Hughes’ poems, both these aspects of his “wet–footed god of horizons” are present. In April, the month of springtime and renewal, its “wobbling water–call” conjures the moon: “new moons sink into the heather” and rise from it “full golden” and bulging. The sexual connotations are implicit and are reinforced by the procreative connotations, luxurious sound and active tense of “bulge” (the word is also emphasised by its typographical separation from “full golden moons”). This, together with the impression of temporal contiguity, which is given by coupling the two events in linked lines, suggests the magical fecundity of the moon, which rises from the Earth radiant with the promise of new life.

In the second poem, the curlews are associated not only with the Goddess through the poem‘s imagery, but also with the “nameless and naked” energies themselves. Like a human soul leaving its earthly body, they “slough off” the Goddess’s “maternal”, earthy environment and lift skywards. away from the “magic circle” of the moorland horizons which Hughes once saw as a “high definite hurdle” blocking physical and mental escape from the valley (The Rock). They are spirits of light and water which, like the nymphs in Porphyry’s essay On the Cave of the Nymphs6, enact the soul’s perpetual cycle of descent and return between temporal and eternal worlds.

In the freedom of air, the poetry imitates the rhythms and pattern of the birds’ flight as, with their sinewy bodies, their voices and their “trembling bills”, they connect the elements – earth, air, water and light: lifting out of earth, negotiating air with masterly skill, they lance the water with their voices to release the light trapped beneath this “skin”. The ultimate result is the release into their world, and ours, of something inspiring awe, or ecstasy, or both: something which nourishes the soul.

Another common moorland bird used by Hughes to invoke the fecund power of the Goddess is the snipe. In mythology and folklore, snipe, because of the aerial drumming noise they make, are Rain–birds or Thunder–birds, attributed with the magical power of rain–making and, consequently, linked with fertility gods. In Remains of Elmet, on the open moors, “snipe work late” whilst the fleeing wraiths from Mankind’s history perform in ghostly drama all around them (ROE.19). The purpose of their work becomes apparent in ‘Spring–Dusk’ (ROE.66), where Hughes uses their energy to re–connect Heaven and Earth. Their drumming becomes the invocation of supernatural powers by a “witchdoctor” or shaman, whose flight draws down the moon to a wounded and dying Earth to promote new life. The imagery likens them to doctors swiftly suturing a body’s wounds, and their healing, in this poem, is magical, fertile and beautiful.

Another common moorland bird used by Hughes to invoke the fecund power of the Goddess is the snipe. In mythology and folklore, snipe, because of the aerial drumming noise they make, are Rain–birds or Thunder–birds, attributed with the magical power of rain–making and, consequently, linked with fertility gods. In Remains of Elmet, on the open moors, “snipe work late” whilst the fleeing wraiths from Mankind’s history perform in ghostly drama all around them (ROE.19). The purpose of their work becomes apparent in ‘Spring–Dusk’ (ROE.66), where Hughes uses their energy to re–connect Heaven and Earth. Their drumming becomes the invocation of supernatural powers by a “witchdoctor” or shaman, whose flight draws down the moon to a wounded and dying Earth to promote new life. The imagery likens them to doctors swiftly suturing a body’s wounds, and their healing, in this poem, is magical, fertile and beautiful.

In this poem, too, Hughes, the shaman/witchdoctor/poet, makes an invocation of his own which brings soothing and healing energies to the sequence. The poem revolves around the witchdoctor’s “drumming in the high dark” in theme, atmosphere and form, moving from a frail, broken state, through an urgent, rhythmic, circular “stitching”, to a soothing gentle balance which culminates in the unity and promise of “eggs”.

‘Spring–Dusk’ comes in the middle section of the Elmet sequence and completes a group of poems dealing with the elements. Its healing, fertile power is necessary to balance those fierce and destructive energies which scour and purify the land, preparing it for a new beginning. The poems from ‘High Sea Light’ to ‘Spring–Dusk’ lift us from the dark valley into the freedom of the moors. There, Hughes explores the interplay of earth, water, light, air and a few moorland animals in terms of energy and action, and the motifs of worship and sacrifice, which run through these poems, culminate in moonlit healing and the promise of new life.

Light, which early in the sequence was represented as “The fallen sun” (ROE.23) held by suffering “worn–out” water, becomes, in ‘High Sea–Light‘ (ROE.62), glowing and pearly. On the moors, the sun and water which share the exhausting lives of the men and women of the valley become free and energetic. The streams absorb heaven’s glow with eager “gulping mouths”, and the light energises the “busy dark atoms” of an Earth which Hughes links with the sun in his final image. Here, Earth is both a “stone of light’ and “wreathed“ by that light; an image similar to that used in ‘Walking bare’ (CB.54), where the protagonist is described as a planetary “spark” swept by the sun’s corolla.

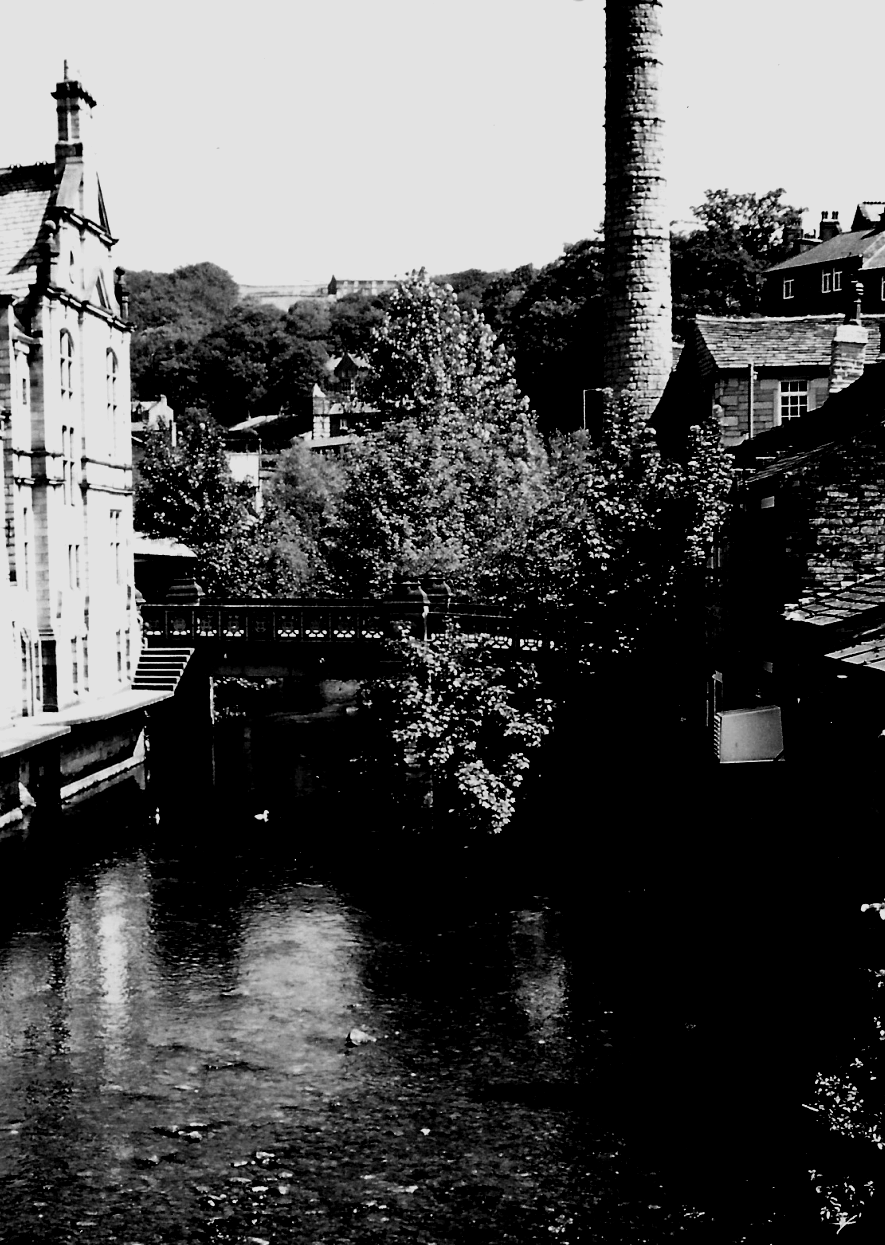

The contrast is seen, too, in the accompanying photographs, and is most marked if the photograph following ‘It Is All’ (ROE.23) is included in the comparison. In the picture opposite this poem, light glows softly from alley paving stones, but it is surrounded by darkness, trapped in the polluted water of the clog–worn gully, and blocked by the blackness into which the path leads. Similarly, the photographs on page 24 show a disk of light reflected in dark turbid water, looking very like a sun trapped beneath the water’s surface. In contrast with these, the picture above ‘High Sea–Light’ (ROE.62) shows a stone causey glowing with a light which becomes soft and pearly where it robes the gentle curves of the open moors beyond. We see a pathway of light leading to the freedom of the lit moors; a path by which to escape into the “lark–rapture silence”. Light and soul, which are trapped in the valley, are here released from human constraints and can work with the other elemental energies to revive the damaged Earth.

The Earth, in this small group of poems, is a living organism, its body a “prone, horizon–long / Limb–jumble of near–female” (ROE.63) energised by the light, scoured by wind, and oppressed by the “shadowy violence” (ROE.50) of the skies. In ‘Where The Millstones of Sky’ (ROE.66), Hughes captures the peculiar weight of grey Yorkshire skies which seem to rotate above the Earth like a millstone, altering the colours of the landscape and making light and shadow “purple–fine”. The wind and rain which such skies portend do, indeed, grind away the Earth’s surface “skin”, to expose the “raw true darkness” of the soil, which seeps like blood from the wound.

Trees, like the one in ‘A Tree’, are “stripped” of leaves and tortured by the elements into contorted and cruciform shapes. Few survive, and generally the land is naked but for grass and the few tiny plants, such as harebell and heather. These flowers bring seasonal colour and life to the scene, covering the “huge bones and space–weathered hide” of the living Earth with “blueish delicate milk” (ROE.114), and clothing it in “sea–purple” Tyrian hues, as if with the cloth woven by the Naiads in the Porphyry’s essay on The Cave of the Nymphs. The “euphoria” associated in the poem with the flowers connects them, like the moorland animals, with the life energies which endure and multiply:

The upper millstone heaven

Grinds the heather’s face hard and small.

Heather only toughens.

And out of a mica sterility

That nobody else wants

Thickens a nectar

Keen as adder venom (ROE.48).

Euphoria is generated, too, by this nectar, which is a portion of the universal energies, an ambrosia which attracts the bees and which thereby performs its essential role in the interconnected patterns of natural life. As in “the moony shades and hills” of Blake’s Beulah

…the Flowers put forth thier precious Odours

And none can tell how from so small a centre, comes such sweets

Forgetting that within that Centre Eternity expands

Its ever during doors (Mil. 34:47–49).

Porphyry, too, connects nectar with intoxication, quoting Greek myths and rituals, and explaining its “relationship to purification, to prevention of decay and to the pleasure of descent into the flesh” for souls, “whom the ancients specifically call bees” and who are also priestesses of Demeter, the Goddess7. Such conjoined good and bad qualities are conveyed in ‘Heather’ (ROE.48) by Hughes’ description of the nectar as “keen as adder venom”.

Where it is not clothed with harebells and heather, the living body of Earth is scoured by the elements. and Hughes envisages its silent, almost barren, expanses as an “agony of numbness” in which the infrequent, watery sun appears like a nurse who “swabs and dabs” the bleeding wounds (ROE.66). The essence of this metaphor is “the idea of nature as a single organism” which, Hughes once wrote, was “man’s first great thought, the basic intuition of most primitive theologies”9. His use of it here, however, is Platonic and Alchemical in its linking of Earth with the divine and in its cleansing purpose. In the words of alchemist. Thomas Vaughan,

the texture of the universe clearly discovers its animation. The Earth … represents the Grosse, carnal parts. The Element of Water answers to the blood … The Aire is the outward refreshing spirit, where this vast creature breathes, though invisibly1 .

And the alchemical cleansing and healing power of the sun’s celestial fire is, as in Cave Birds, the means of Earth’s purification.

Despite this cleansing, the world of the moors and world of the valley are still separate. Men on the moors experience the elemental freedom, regaining, as in ‘Football at Slack’ (ROE.68) and ‘Sunstruck’ (ROE.70), some of their childhood energy and playfulness. But they are out of their depth in this elemental world, and unable to escape the pull of the valley.

In ‘Football at Slack‘, (ROE.68) despite the atmosphere of jollity and the merry plunging, bouncing, spouting, bobbing and flying of men and ball (which share movement and action as if connected by invisible strings), the press of the weather pervades the poem. We see the men tread water whilst the “winds from fiery holes in heaven”, the mad “glare light”, and “the steel press” of rain, loom over the playing fields and the valleys and “a golden holocaust” lifts “the cloud’s edge to watch them”. Here, and in ‘Sunstruck’, the dialectics of light and darkness, freedom and imprisonment, temporal and eternal, and of man’s inner and outer worlds, are joined in poems which are full of humour and playfulness but which convey, also, the ominous power of the sun.

The “bunting colours” of the “merry–coloured” men on the football field, and the image of cricketers “stampeding / Through the sudden hole in Saturday” (ROE.70), give the impression of a brief holiday from the routine of the working week. That this routine is of stultifying “misery” is most apparent in ‘Sunstruck’, where each escape and return of the ball parallels the players’ urge to escape, and the inevitability and disappointment of recapture. Even at play on the cricket pitch the men’s bodies remain Earthbound, confined within the “cage of wickets”, physically “cornered”, “pinned” and “chained”: only their hopes and dreams fly with the ball, but are “caught and flung back, and caught, and again caught”.

In the paradigm of a cricket game, the complete escape of the ball is impossible: in our material world, complete escape for the spirit is impossible. ‘Caught’ and ’bounced‘, and ‘clubbed’ into submission by the circumstance of our lives, our defeated spirits submit and our eyes turn from the seemingly impossible vision to the dregs and crumbs within our reach, just as the cricketers’ eyes

glad of anything, dropped

From the bails

Into the bottom of a teacup,

To sandwich crusts for the canal cygnets.

Yet, the urge to escape the imprisoning pattern of the abstract “theorem” of our routine existence, the urge to return to the Source and make contact with the natural energies which once fuelled our childhood play, persists, and so the cycle is repeated. As in the football and cricket games of these men, the exhilarating experience of flight, although momentary or vicarious, changes us so that we return from it “like men returning from a far journey”, exhausted but refreshed. In this repeated experience lies hope, and so, in his poems and in the structure of the sequence itself, Hughes repeatedly draws us, in imaginative flight, from the dark and stultifying atmosphere of the valley.

If the poems from ‘High Sea–Light’ to ‘Spring–Dusk’ depict the power of the elemental energies to heal the Earth, then ‘Football at Slack’ and ‘Sunstruck’, although light and humorous in part, demonstrate the feebleness of Man’s own efforts to free himself from darkness.

In both poems the men are dwarfed by the land and the weather. The footballers, precariously exposed on a “bareback of hill” between “plunging valleys”, are awed by the piled “hills darkening around them”. On the sodden slopes they defy the weather which threatens to wash them back into the “gulf of treetops” and the “foundering” world of the valleys. Commenting on the poems, Hughes said: “On Hebden ridge(?) between two steep sided valleys was a football field, precariously balanced. From my bedroom window I could watch the play. These verses describe the scene on what memory produces as a typical day”10.

The cricketers, too, are limited in their play by the “shaggy valley parapets / Pending like thunder”, which can be seen overshadowing their homes in Fay Godwin’s accompanying photograph. They are “burned” by the sun which dazzles and nags at them, inducing a kind of hallucinatory madness as it did in the early poem ‘Sunstroke’ (THCP.86) and in Hughes’ story, ‘The Harvesting’ (W.82–92). “Sunstruck”, their “brains sewn into the ball’s hide”, they identify with the ball and imagine the impossible release – “The ball slammed flat! And the bat in flinders! The heart soaring!”, and the “wild” affirmation of their hopes of freedom. In their sun–induced hallucinatory dream they believe they can escape the dark valley. But their imagination stretches only as far as the flight of the ball in their unimaginative games, and neither spirit nor body is able to withstand exposure to the sunlight for long. Driven by a “cross–eyed, mid–stump, sun–descending headache”, they turn in relief to the “cool sheets and the black slot of home”, despite the slavery and negation which these entail.

The lack of imagination and spiritual strength which precipitate this return to the valley are not, however, due to an innate deficiency in Mankind but result from a lack of maturity. Certain aspects of the poems convey this: such as the uninhibited, childlike energy which the men bring to their games, and their careless disregard of the prevailing weather. The narrator’s birds–eye perspective, too, reduces the men to toy–like figures whose slightly ludicrous actions, orchestrated by their “elastic” connections with the ball, remind one of a child’s game in which all the pieces are joined together by strings hidden beneath a board11. As in Blake’s poem,

Such were the joys

When we all, girls & boys,

In our youth–time were seen

On the Ecchoing Green12.

The spiritual immaturity of Mankind has been suggested throughout the Elmet sequence by the egocentricity and foolishness of the peoples’ aims and actions. It was symbolized in the aimless children of ‘Mill Ruins’ (ROE.38), and it is clearly stated towards the end of the sequence in ‘Tick Tock Tick Tock’ (ROE.120) where, in an extended metaphor based on J.M. Barrie’s story of Peter Pan (the ‘ageless boy’ from Never Never Land) the fate of the Calder Valley is attributed to the “everlasting play” of a whole society.

Because of its immaturity, Mankind is, like the football and cricket players of Hughes’ poems, trapped by its own limitations. For as long as we seek the sun, our situation is not without hope. But because of our divided state and our single vision, our spirit – the divine spark within us – has grown weak. Like Blake’s sleepers in Ulro, we need to be awakened, taught the error of our ways, and shown the path of enlightenment. Otherwise, we have no choice but to keep returning to the dark “valley cauldron” (ROE.121) until the “golden holocaust” finally occurs.

Throughout the Elmet sequence, Hughes prepares for the final apocalyptic event which was prefigured in his dream/vision of the Angel. By the agency of the elemental energies and, in particular, through the cleansing power of celestial fire, he works towards the golden holocaust in which light will be released from the valleys and the fallen souls released from the generative world so that, as in the The Revelation of St. John the Divine, “a new heaven and a new earth may be established”13.

Time, in the sequence and in the poems, is not wholly linear. It makes inter–related spherical patterns, circling back on itself so that the early days of this society are meshed with later events, and figures from the past are invoked in modern settings. Its movement at times resembles Yeats’ spiralling Gyres, but it is also that of Nature whose revolutions are continuous and endless. So, the fall of the people and their society into Earth occurs many times and is interwoven with the exposure of everything to the elements, and with the repeated return of the spirit to the moors, as “it does what it can to save itself alone” (ROE.14).

This repetition and intermeshing of themes and events produces an impression of formlessness, such as was found by some early critics in Blake’s Jerusalem. Yet, this formlessness is apparent only if one expects events to be described chronologically, which in Jerusalem and Remains of Elmet they are not. Paley, commenting on Jerusalem adopts the word ‘synchronic’ to describe the way that Blake, like Ezekiel and John in the prophetic books of The Bible, describes a single event in a number of different ways14. Remains of Elmet resembles all these writings in its ‘synchronic’ form and in its apocalyptic theme, and there are other parallels in the way Hughes’ apocalyptic vision is expressed.

The most obvious of these parallels is, of course, the angelic vision which has already been discussed, but the cyclic recurrence of destruction and death in Hughes’ poems is like the repeated devastation wrought by the various angels in Revelation. The great elemental disturbances of the biblical visions, the “peals of thunder and sounds and flashes of lightning” (Revelation.4:5), find parallels in the Calder Valley weather which “Spins electrical terrors / In the eyes of sheep” (ROE.19). And the poisoning of the Earth’s waters occurs just as surely through modem industrial pollution, which has created the “veto of the poisonous Calder” (ROE.70). In each case, the vision is of war and death and “unending bleeding”, like the “rummaging of light / At the end of the world” (ROE.26). And the smoke darkened skies of the Calder Valley provide us with a realistic foretaste of the “bottomless pit” where:

there arose a smoke out of the pit, as smoke of a great furnace; and the sun and the air were darkened by reason of the smoke of the pit (Revelation.9:1).

Clearly, however, Hughes does not use Christian symbols in their usual biblical form. He transposes them into modem settings, embeds them in nature, and creates his own myths around them, relying on the resonant connotative power of words like ‘Egypt’ and ‘slavery’ (in ‘Willow–Herb’ (ROE.73), for example) to conjure the biblical myths into the mind of the reader. Similarly, underlying Hughes’ vision of devastation, there is the promise of a natural, rather than a Christian, resurrection. ‘Willow–Herb’, with its reference to “Egyptian walls”; to something that was “Slavery and religious”; and to the “Rusts” and the stagnation of the canal, suggests close parallels with “the cauldron whose rust is therein” of Ezekiel’s vision (Ezekiel.24:6–14). Embedded in the poem, however, is the almost hidden symbol of a serpent which has biblical, natural and cosmogonic significance.

The serpent, toothless but dangerous, good and evil, is present in the alliteration and sibilance of ‘s’ throughout ‘Willow–Herb’. The “ripples” of its “slack”, “gleam–black” body form the slow–moving serpentine canal which we see in Godwin’s photograph, and, in the final line of the poem, its ambiguous smile is symbolised in the Willow–Herb – the first weed to arrive when there is disturbed ground, and a common weed amongst city rubble where its “vandal plumes” mark the beginning of natural regeneration. In the circularity of the poem, where the title is integral and important to the text, so that Hughes starts and ends with Willow–Herb, we see the cosmic serpent – the Uroborus – symbol of eternity and regeneration.

The serpent, toothless but dangerous, good and evil, is present in the alliteration and sibilance of ‘s’ throughout ‘Willow–Herb’. The “ripples” of its “slack”, “gleam–black” body form the slow–moving serpentine canal which we see in Godwin’s photograph, and, in the final line of the poem, its ambiguous smile is symbolised in the Willow–Herb – the first weed to arrive when there is disturbed ground, and a common weed amongst city rubble where its “vandal plumes” mark the beginning of natural regeneration. In the circularity of the poem, where the title is integral and important to the text, so that Hughes starts and ends with Willow–Herb, we see the cosmic serpent – the Uroborus – symbol of eternity and regeneration.

Characteristically, Hughes’ use of the Willow–Herb plant in this poem is both realistic and symbolically precise. Through its name, the plant is linked with the prophetic and divinatory Willow Tree of the Moon Goddess. It is also commonly known as ‘fireweed’15, and its appearance in this poem presages the moment in ‘Under the World’s Wild Rims‘ (ROE.79) when, for the first time in the Elmet sequence, the sun’s fire enters the “submarine twilight” of the valley, falling as sunbeams into the moon–crescent “horns” of Willow–Herb flowers, and thus symbolically joining sun and moon, Heaven and Earth, body and soul. That Hughes’ imagery is alchemical as well as natural is clear, and this is supported by the fact that although the mention of horned flowers suitably continues Hughes’ metaphor of vandal invaders, the description (contrary to Hughes’ usual practice) is not botanically accurate: it is, however, consistent with alchemical symbolism, where the crescent moon is a symbol for the receptive Soul16, the vessel in which the synthesis occurs.

Hughes’ use of Christian, biblical, mythological and natural symbolism is especially apparent in his treatment of Earth’s rocky substrate in Remains of Elmet. The biblical symbolism of rock as the Lord (e.g. Psalm 18) and as the tomb/womb from which Christ was resurrected, is an important part of Hughes’ prophetic message, but its Christian framework is submerged in the diverse myths which Hughes, here, weaves around it.

The ancients, as Porphyry noted, used rock to symbolise the first matter, dark, infinite and without form (Porphyry.24). From this matter the world was made, and "from the presence and supervening ornament of form … it is beautiful and pleasant17.

In Elmet, Nature and Mankind impress changing form on the rock’s surface: “Heather and bog–cotton fit themselves” (ROE.50) to it, softening and ornamenting it with a “grizzly bear–dark pelt” (ROE.48); Nature seasonally transforms it; and Man quarries and carts it, shaping it into mills and houses and walls. Yet, although Hughes makes use of this ancient philosophical concept of matter and form, throughout the Elmet sequence he personifies the rock.

The natural, physical changes in the ‘Big Animal Of Rock’ (ROE.44) which Hughes creates, reflect the changes that take place in the Calder Valley: and the animal’s song serves as a metaphor for the immutable soul which is the essence of its mutable bodily form. In its association with Man, rock is “Tamed” (ROE.40), loses its spirit, forgets “Its earth–song” and is “Content / To be cut, to be carted / And fixed in its new place” (ROE.37). In this state it becomes “soul–grinding sandstone” (ROE.40), sharing the dispiriting world of the people, and imposing as well as receiving “four–cornered, stony” (ROE.37) spirit and form. From the “Roof–of–the–world–ridge” in ‘Wild Rock’ (ROE.40), the millstone–grit. which is the prevailing geological rock of the Calder Valley, now overlooks the smoking pit of the valley where sheep fleeces are “blown like blown flames”. The quarried rock–face becomes an ironic “Heaven” (ROE.40), coloured and tainted by its proximity to the valley. “Oak–leaves of hammered copper, as in Cranach” are beautiful but fixed, as in one of Cranack’s religious paintings of Adam and Eve at the moment of temptation in the Garden of Eden18. And, just as the rhythmic and typographical balance of the first three lines of the poem contrasts wild rock with tamed rock, and natural millstone–grit with a ‘soul–grinding’ sandstone, Fay Godwin’s photographs on pages 40 and 41 depict Heaven and Hell, showing the contrast between them. From the dark. looming, wild rock–face of the quarry in Godwin’s photograph on page 41, one of Heaven’s “angels” (ROE.104) (looking like a Paschal Lamb) stares down into the fixed order of the valley on page 40, where mill chimneys symbolise slavery and where – in “rain and rain… and rain”, “Wind” and “Cold” … the people and the land tremble under a haze of smoke.

Away from the valley, however, the ‘Big Animal Of Rock’ is “In its homeland” (ROE.44). Crouched on the moors, like the dark rock in Godwin’ photograph (ROE.45), it is the foundation stone of the natural world: Mother to “root and leaf”; “kin” to the animals and birds, bodies and souls, of the generative world who “visit each other in heaven and earth”. In the metaphor of worship, which pervades this poem, the rock is the “cantor”, the precentor who leads the spiritual song at this “Festival of Unending”, this festival of the Goddess of Life and Death who, like the hag Cerridwen, “eats her children”19. From the cantor/rock comes the sacred music which connects the multifarious changes around it to a single spiritual theme; and the world of Elmet, Hughes’ poetic world which is also our world, is the church in which it officiates. Its songs punctuate the poetry, stopping whilst other rituals take place, but always returning to lead the worship until the final “Hallelujah!” in ‘The Word That Space Breathes’ (ROE.117) announces “The Messiah / Of opened rock”.

Early in the Elmet sequence this ‘Big Animal of Rock’ kneels singing amongst the stone ruins which are the “cemetery of its ancestors”. Through “lasting purple aeons” (ROE.48) the wind “curries” its heathery, grassy pelt; and, as the sequence progresses, people come and go, and are “ground into fineness of light” (ROE.50) by the revolving skylines where the millstone–grit of Earth (Hughes puns on the geological name) and the “upper millstone heaven” (ROE.48) touch. The traces of human life are ground away; the elements cleanse the land; and, at last, the “swift glooms of purple”, mingling skylines and heather, wind, water, earth and light, swab “the human shape from the freed stones” (ROE.103).

As this purification of Earth progresses, the land becomes bare and wintry, as if the awaited “star–drift / Of the returning ice” (ROE.48) approaches. Dramatic changes begin to occur. The magic circle of hills is broken, their “fragments” drift apart (ROE.92) and the Goddess (in the disembodied semblance of the Wolf–goddess, Cerridwen), “That cannot any longer on all these hills / Find her pelt”, vents her wrath on the world, rolling it in rain “Like a stone inside surf” (ROE.95) whilst the elements from her “cauldron of thunder” (ROE.100) crash, splinter and claw the closed doors and the closed minds of those who suppress and exclude her. At last, the “howling skylines” (ROE.103) close in, the stones are “freed”, and, with the beggar/angels watching from the “lightning–broken huddle of summits” (ROE.104), the wind presses everything “towards ice” (ROE.107)20.

In the photographs on page 108 and 109 we see the star–drift / snow–drift ice–age begin. The change from empty moorland, ridged by the horizontal plough–lines of ancient and primitive farms, to the broken walls and fences leading into a snow covered landscape which fades away to nothing in the distance, marks the completion of one more cycle. In the loss of definition towards which the eye is led in the second photograph, the world returns to elemental chaos; to matter in which form can no longer be distinguished; to a wintry white drift of nothingness.

The two poems which immediately follow these photographs dwell on this nothingness. ‘Widdop’ (ROE.110) is at a first reading one of the least satisfactory poems in the Elmet sequence, because of certain internal ambiguities. The mood of the poem is unclear, but that it is about nothing and nothingness is apparent from the repetition of these words within the poem. There is negativity in the imagery – the lake is “frightened”, the wind “trembling” and the grass “in fear”. There is artificiality, too: Widdop Reservoir does not have the natural “happiness” of “broken water at the bottom of a precipice” (ROE.13), it has been “put” there by “someone”, and the trees around it blindly “act” a pretence of reality. Yet the “stony shoulders” of the earth “broaden to support” the lake as if accepting it; the “trembling” of the cosmic wind may be due to fear or awe; and the gull, a heavenly visitor associated with the souls of seamen and travellers and with ploughed fields and fertility, “blows through” the veil of clouds out of the cosmic nothingness into the nothingness of this scene, and may be viewed with hope or despair, or perhaps both.

In the form of the poem, the end–stopped stanzas physically and rhythmically isolate the various components of the scene from each other. Disjointed and repeated phrases reflect a discontinuity in the natural harmony of the place described, but there is, also, a suggestion of tentative acceptance – the earth supports the lake, the wind sniffs at it, the trees combine to give it reality, and the “heath–grass” creeps close.

Ultimately, the poem circles back to its beginning so that the lake, like the gull, has only a fleeting presence, coming through “a rip in the fabric” of time and space, “out of nothingness into nothingness”. This, perhaps, is the import of the poem: its nothingness creating a pause in the spiritual music, a stillness in the cycle of regeneration which is like Eliot’s “moment in and out of time”21.

If ‘Widdop’ creates a pause, a disjunction in the sequence, then in the next poem, ‘Light Falls Through Itself’ (ROE.113), movement and harmony are re–born. In the photograph of snow which accompanies the poem, the crystalline whiteness of snow reflects and transmits the light which falls on it, so that light literally falls through itself creating an almost formless chaos of light. Similarly, in the photographic process, the light falling on the molecules of photographic emulsion has been trapped so that the resulting image is almost totally of whiteness and light.

From this elemental chaos of light, Hughes creates an alchemical metaphor of rebirth. The snowy whiteness resembles the crystalline spiritual purity achieved in ‘Walking bare’ in Cave Birds (CB.54), but here it is transformed by the reality of the Calder Valley. Like a purified soul, stripped of “most of itself and all its possessions”, light falls “naked” into the poor stripped earth of Elmet where, in the central images of the poem, warmth and life are breathed into it. The “poor cow”, whilst being a realistic part of the poverty stricken landscape, nevertheless embodies the maternal, succouring qualities of the Mother Goddess; and the wind fanned flames trembling at the blue crucible–edge of the far skylines, fuel the transmutation. So, the pale, “threadbare”, winter light of the sun kindles life in the windswept snowscape: light is reborn from light, and it “creeps” and “cries” and “shivers”, like a baby, in the grass.

With the re–birth of light, the ice–age of winter passes and, fuelled by the strengthening sun, Nature’s resurgence begins. The spirit, too, revives. ‘In April’(ROE.114), the time of spring and renewal, the “black stones” which have survived the “pre–dawn” chaos of the Earth emerge, as if “from under the glacier”, to lie “Healing and sweetening” in the sun. Hughes” image of a soft, shaggy, cat–like creature, stretched ecstatically in the sunshine, beautifully captures the mood of a warm spring day when the land is newly softened by vegetation and looks fresh and peaceful; and the image re–introduces Hughes’ earlier metaphor of the rock–animal, the cantor, which now emerges to lead the Messianic singing. At the same time, this “soft animal of peace” symbolically parallels the biblical “covenant of peace” (Ezekiel.37:26) made by the Lord with the people of Israel after their resurrection in the valley of bones; and its emergence can be equated with the appearance of the Lamb in Revelation (14:1–3), which is accompanied by the music of deliverance.

Now, the music of the cantor–rock is heard again, leading the elemental choir in Hughes’ own music of deliverance. In ‘The Word That Space Breathes’ (ROE.117), drawing on the great choral tradition of the North of England, in which Handel’s Messiah is widely known and well–loved, Hughes creates a Messiah of his own. Handel’s oratorio celebrates the birth, Passion, death and resurrection of Christ; and the ‘Hallelujah Chorus’, which is perhaps the best known part of the work, glorifies Christ risen from his sepulchre of rock. Hughes, too, celebrates “The Messiah / Of opened rock”, but his song owes more to the ancient sacrificial rituals associated with Nature’s cycles of death and rebirth, than to the Christian celebration which replaced them22.

The parallels with the prophetic books of The Bible, however, are strong. The Word, the promise of Man’s redemption, which is to be heard at the resurrection, is here, as in Ezekiel’s vision, the breath of the wind blowing through the “tumbled walls” (ROE.117) of the land and breathing life into the scattered bones of the people (Ezekiel.37:9–10). And, as in the Revelation, this disembodied voice is accompanied by the music of the people, the land and the skies, a beautiful, sad echo of the singing once heard in the valleys but, nevertheless, a ‘Song of Deliverance’,

as it were the voice of a great multitude, and as the voice of many waters, and as the voice of mighty thunderings, saying, Alleluia: for the Lord God omnipotent reigneth (Revelation.19:6–7).

In Hughes’ poem, the walls which the people so painstakingly built, the enclosures into which their lives and cares went ‘Like manure’ (ROE 33), guide the spiritual wind–song (as the eye is guided by them in Fay Godwin’s photograph), leading it upwards “From every step of the slopes” to a crest where clouds and walls meet. As if in a musical crescendo, “The huge music / Of sight–lines” is gathered into a dramatic focus which joins Heaven and Earth, and this climax is echoed in the final stanza of Hughes’ poem like an ‘Hallelujah!’, marking the moment when the Word and The Messiah become One and the circle of the poem is complete.

In many ways, it is a pity that ‘Heptonstall Old Church’ (ROE.118) and ‘Tick Tock Tick Tock’ (ROE.120) intervene between ‘The Word That Space Breathes’ and the next poem describing apocalyptic events, which is ‘Cock–Crows’ (ROE.121). The first of these poems reiterates the fallen state of Elmet, the literal and metaphorical extinction of light in the valleys, and the freeing of the land as “The valleys went out” and “The moorland broke loose”.

Such reiteration is consistent with the pattern of cyclic recurrence which has prevailed throughout the sequence, and it reflects the synchronic form of the biblical prophecies, but it also dissipates the elated mood established by the previous poem and breaks the momentum. The second poem, ‘Tick Tock Tick Tock’, begins to re–establish this momentum, and together the two poems act like the restatement of a musical theme in the approach to a grand finale. As such, they should increase, rather than dissipate, the tension and build towards a greater climactic release. It is doubtful whether these two poems actually achieve this.

‘Tick Tock Tick Tock’, however, concerns Hughes’ own prophetic role in the sequence of events and is part of the group of poems dealing with his childhood which will be discussed separately. The theme of time which dominates this poem, and the way in which Hughes’ unique perception of impending danger is encapsulated, appropriately link it to the coming events.

The last three poems of Remains of Elmet are the climax of the sequence. Each one of them is part of Hughes’ visionary prophecy of transformation, and part of the poetic alchemy by means of which the trapped light will be freed from the valley, the souls released, and, as in Revelation (21:1), “a new heaven and a new earth” is created.

The title of ‘Cock–Crows’ (ROE.121), which is the only place in which the word ‘cockcrows’ is hyphenated, provides the first hint of the poem’s underlying theme of the renewal of Earth. By hyphenating the two words Hughes not only suggests an initial imperative bird–call from which the chorus grows, but also makes mythological allusions. As in Cave Birds, the cock is a common symbol of unenlightened Man, it is also the symbol of the reborn solar hero and of Hermes Mercury, the guide of souls. Here, it is separated from, but linked to the crows, thus connecting the bird of dawn, which is also a symbol of the fool, with the bird of darkness, which is also the oracle bird of the sun&gods. Thus, in a single hyphenated word, Hughes embeds the complex idea of the consubstantiality of opposites which allows change and renewal.

Hughes vision in ‘Cock–Crows’ has many precedents. The prophet Ezekiel, set by God “upon a very high mountain” (Ezekeil.40:2), saw the holy temple of his people of Israel and, like the rising sun, “the glory of the God of Israel came from the way of the east … and the earth shined with his glory” (Ezekiel.43:2). John, too, in Revelation, “saw heaven opened” (Revelation.19:17) and “an angel standing in the sun” (Revelation.21:10): he, too, was carried “away in the spirit to a great and high mountain” from which he was shown the new Jerusalem of “pure gold” (Revelation.10:19).

The imagery of mountain tops, sunrise, gold and splendour, is common to these biblical visions, as it is to that of ‘Cock–Crows’ and to the final part of Blake’s Jerusalem. Hughes’ vision, however, owes more to Blake than to any other visionary prophet, and his opening lines echo those of Blake’s poem addressed ‘To the Christians’ which begins:

I stood among my valleys of the south

And saw a flame of fire, even as a Wheel

Of fire surrounding all the heavens: (Jer.77:43–45).

These lines precede Chapter 4 of Jerusalem in which the awakening of Albion and Jerusalem takes place, and the vision described by Blake is one of natural oppression and disaster akin to Hughes’ vision in ‘Ballad from a Fairy Tale’ (THCP.171) (which also echoes these lines) and ‘The Angel’ (ROE.124). In ‘Cock–Crows’, however, Hughes has left the valley to stand on “a dark summit, among dark summits”. As elsewhere in Remains of Elmet, these moorland summits become like wave–crests23 and, in the “Tidal dawn splitting heaven from earth” (the phrase suggests the appearance of a new world as well as a new day), Hughes envisions the parting of the dark primeval chaos of the waters to reveal, like the parting valves of a rough grey oyster, the living colour and beauty within. His imagery, here and throughout the poem, fills the imagination with the light, colour and sound of Cerridwen’s cauldron which, like an alchemical crucible, ferments a fiery mixture that briefly allows us to “taste–gold”.

The dawn which Hughes sees and hears is a magical awakening of the dark valley of Elmet. Equivalent events occur in Blake’s Jerusalem at the awakening of Albion, who rose from his rock like the sun with

the wrath of God, breaking bright, flaming on all sides around

His awful limbs: into the Heavens he walked, clothed in flames,

Loud thund’ring, with broad flashes of flaming lightning & pillars Of fire, (Jer.95:6–9)

Blake’s etching shows Albion (who is also Los and the sun) rising from the rock–strewn earth, naked, and phoenix–like in flames24, just as in Hughes’ poem the “fire–crests / Of the cocks” (symbols of the sun and a new dawn) rise from the dying valley of Elmet.

Although Hughes’ imagery is quite different to Blake’s and is founded in the reality of a Calder Valley sunrise, the parallels are clearly present. Just as, for Hughes, the cockcrows kindled “under the mist” before “clambering up the sky”, so Blake’s sun/Albion is seen “in heavy clouds / Struggling to rise, above the Mountains” (Jer. 95:11). Hughes’ “sickle” cockcrows, “tossed clear” of the valley mist and “soaring harder, brighter, higher”, until they burst “to light / Brightening the undercloud”, are like Albion’s’s “arrows of flaming gold” (Jer.95:13), which flew forth into the heavens from his “horned Bow” (Jer.98:3) until “the dim Chaos brighten‘d beneath, above, around” (Jer.98:14). The bubbling “valley cauldron” resembles the “Furnaces of affliction” (Jer.96:35) which, in Albion’s vision, became “Fountains of Living Waters” (Jer.96:36) out of which “The Sons & Daughters of Albion” (Jer.96:39) rose from their sleep. And the rhythm and diction at the central climax of Hughes’ poem echo those of Blake in their exultant, expanding, glorious power.

From the first hint of life and colour, as the “tidal dawn” begins to separate the dark Heaven from the dark Earth, the rhythm and momentum of the poem reflect the gradual awakening of the valley. The cockcrows kindle first, like a new fire, “deep” under the mist, “sleepy” and “bubbling”. Then, in a couplet full of soft sibilance, a caesura stops the “tossed clear”, escaping sound; and, by a paradoxical coupling of words, the “rocket” becomes a ”soft“ glow falling back into the mist with the dying fall of the second line. So, the form reflects the content, and continues to do so as, in the next stanza, the sound, movement and colour build to a crescendo. The harshness and forcefulness of words like ‘soaring’, ‘tearing’, ‘bursting’, ‘challenge’, ‘hooking’, are softened by the imagery of rounded “bubble–glistenings”, bringing light and beauty to the dark “undercloud”, and by the warmth of the redcombed “fire–crests of the cocks” and the melting echoes of their crowing ‘hanging smouldering from the night’s fringes”. Now, the world is lit by the internal fires of the cauldron, bringing an end to the dark valley night, and now the brimming molten sound becomes “A magical soft mixture boiling over,/ Spilling and sparkling into other valleys.”

So, the climactic rhythms of the 4th stanza precede the spreading of light and beauty over the Earth; and its repetitions, mood and rhythms resemble strongly those of Blake’s vision of Albion as he cries

Awake, Awake Jerusalem! 0 lovely Emanation of Albion,

Awake and overspread all Nations as in Ancient Time;

For lo! the Night of Death is past and the Eternal Day

Appears upon our Hills. Awake Jerusalem, and come away! (Jer.97:1–4).

Hughes’ vision, however, is different to Blake’s. The light that he creates in the dark valleys of Elmet is an effusion of the “magical soft mixture” that bubbles in the Earth Goddess’s cauldron; and the whole process, with its bubbling mixture, its molten and metalic glostenings, its pervasive mists, and its bursts of light and sound, is one in which the alchemical Mothers – Fire, Water and Air – are intimately involved.

Slowly, Hughes’ vision, like the visions of the holy city seen by Ezekiel and John, fades. The fiery cockcrows, “lobbed–up” like “horse–shoes” of glowing metal from the man–made world of “sheds” and “hen–cotes” and “farms” in “other valleys”, fade and die away, “Sinking back mistily”(the phrase applies equally to the cockcrows and the sheds, hen–cotes and farms from which they come) until the last “spark” of life has died.

Hughes’ “golden holocaust” (ROE.68) is over. As the fiery “embers” pale, the Earth is left like a cooling crucible of volcanic lava, “dark rims hardening”, lifeless and smoking. So, all that is left at the end of the poem are sun, water and air – the alchemical ‘Mothers’ – and the formless rock of the Earth. The cycle has been completed. The tidal dawn, heralded by cockcrows, has become the dawn of “a new heaven and a new earth”(Revelation.21:1), and, as the sun climbs into the “wet sack” of the Earth’s atmosphere, Heaven and Earth are reunited and the “day’s work” of re–creation is begun.

In the vision of ‘Cock–Crows’, Hughes sees the fires of the Earth released and the Earth wholly cleansed. Now, in the wake of this golden holocaust, the souls trapped in the world of generation are freed. In ‘Heptonstall Cemetery’ (ROE.122), however, unlike the biblical visions of the apocalypse, Hughes sees no judgment of the dead, no sorting of the sinners from the saved. The risen souls are those of his family and his people – the people of Elmet.

Once again, in the rhythms, theme and content of ‘Heptonstall Cemetery’ there are echoes of Blake’s Jerusalem, for “Thomas and Walter and Edith”, “Esther and Sylvia”25 are like Blake’s “Urizen & Luvah & Tharmas & Urthona”, and “The Sons & Daughters of Albion … Waking from Sleep” (Jer.96:39&41). Similarly, the great radiant glow of sunlight in Fay Godwin’s photograph could well illustrate this same moment of awakening in Jerusalem, when “all around remote the Heavens burnt with flaming fires” (Jer.96:40). Again, however, Hughes’ imagery is different and unique, and the elemental energies which fill the poem are both symbolic and real. The opening lines of the poem recall similar sea/storm imagery in Hughes’ early poem ‘Wind’ (THCP.36), where the disturbances of a stormy night are also linked by a biblical reference with Christ’s promise of salvation26.

In the Elmet poem, the whole Earth is in motion, and under the wind and “spray” the moors become one “giant beating wing” in which the risen souls are “living feathers”. In the cauldron of the elements Man and Nature are united as a single creature and, as the spiritual wind – the divine breath of resurrection – blows across the land, “all the horizons lift wings”, becoming a “dark family of swans” flying towards the Western Paradise (the Atlantic is west of the Calder Valley) which is also the Celtic Otherworld. 27.

In the Elmet poem, the whole Earth is in motion, and under the wind and “spray” the moors become one “giant beating wing” in which the risen souls are “living feathers”. In the cauldron of the elements Man and Nature are united as a single creature and, as the spiritual wind – the divine breath of resurrection – blows across the land, “all the horizons lift wings”, becoming a “dark family of swans” flying towards the Western Paradise (the Atlantic is west of the Calder Valley) which is also the Celtic Otherworld. 27.

Hughes‘ swans, unlike the pure white swans of Aphrodite and Apollo, are “dark”, and it is appropriate that the newborn, newly fledged, souls should resemble cygnets. Most importantly, however, as birds of the Sun God and the Goddess, they are symbols of unity which heal the divisions between Heaven and Earth, Man and Nature, the corporeal and the spiritual. So, harmony is restored and a new beginning can be made. Hughes, in this penultimate poem of the sequence, makes a powerful return to the origin, and this, too, is the final vision of Blake’s Jerusalem:

All Human Forms identified, even Tree, Metal, Earth & Stone, all

Human forms identified, living going forth & returning wearied

Into the Planetary lives of Years, Months, Days & Hours; reposing,

And then Awaking into his Bosom in the Life of Immortality (Jer.99:1–4).

For permission to quote any part of this document contact Dr Ann Skea at ann@skea.com

Go To Next ChapterReturn to Poetic Quest Homepage

Go to Ted Hughes Homepage for more options