“The Mothers…” (ROE.10)

Whilst the first poem in Remains of Elmet introduces the important themes of the sequence, the final poem is, as usual, of special significance and relevance1.

‘The Angel’ (ROE.124) describes a dream rather like the one which Hughes told Faas he had “until a few years ago, dreamt at regular intervals since childhood”. Faas relates Hughes’ poetic interpretations of this recurrent dream to his awareness of the desecration and rejection of ‘Mother Nature’, and he sees Hughes’ poetry as his constant and “deliberate efforts to retrieve her desecrated remnants”2.

The dream, which Hughes described to Faas, and also to his son Nicholas and to two German translators of his work (Letters.708,700), usually involved a terrifying vision of a burning aeroplane. Hughes first wrote of it in ‘The Casualty’ (THCP.42)3, thinking, he said, that if he wrote about it he might stop having it, but “it crept back in various guides”. Faas links it to an Epilogue poem in Gaudete in which the dreamed horror becomes “a viper” which falls from the sun; “a radiant goose dropped from a fire–quake heaven”; and “Something dazzling” which crashes “on the hill field” (G.188). The language and imagery of this Epilogue poem link it, too, to the “a swan the size of a city / A slow colossal power” which pounds towards him “in a storm of pouring light” to become the gigantic “white angel” – the “angel made of smoking snow” – of both ‘Ballad From a Fairy Tale’ in Wodwo (W.166) and ‘The Angel’ in Remains of Elmet.

In both these poems Hughes describes a vision of a disastrous, fiery event, like “a moon disintegrating” over “Black Halifax”4. The swan/angel which emerges from the resulting phosphorescent crater lights the moors as it passes low over them towards him and then disappears “towards the West“. It is a “ghostly” and “brilliant” vision, but Hughes’ “mother’s answer”, when he cries out to her for an explanation, turns “the beauty suddenly to horror” and defines the angel for him as an “omen” – a prophetic vision of dark and dreadful future events.

So, horror, beauty and energy are combined in one powerful symbol which is a perfect example of the “horror within the created glory” (WP.89) of Nature. And in the ambiguity of Hughes’ lines, the dream ‘Mother’, to whom he calls out in ‘The Angel’ but who simply provides an answer in ‘Ballad from a Fairy Tale’, could equally be his own mother, Edith Farrar Hughes, or Mother Nature. The detail which links Hughes’ vision with everyday life, however, and which gave her words “doubled” significance when he was writing these two poems, is his second sighting of the angel’s puzzling halo. This “enigmatic square of satin”, which ripples in the wind of the angel’s flight, he sees again years later in a square of satin in Sylvia Plath’s coffin5. There, he “reached out and touched it”.

The location of the vision in the area around Hughes’ home, his reference to members of his family, and his reluctance to spell out the associated words and events, all suggest its great personal significance. It is very likely that the first version of the poem interprets the vision in the light of Sylvia Plath’s death6. The angel’s disappearance, he wrote, “left my darkness empty”. His ‘mother’s’ words were now under his a feet, “Joined with earth and engraved in rock”, and Sylvia is buried in the hilltop graveyard at Heptonstall. The shock of her death, too, left Hughes, as in the poem, metaphorically “in a valley / Deeper than any dream/… And the valley was dark”.

Significantly, perhaps, by the time that Remains of Elmet was written, Hughes’ mother, Edith Farrar, had also died. She is buried in a grave close by Sylvia’s on the Heptonstall hillside, and now, literally, she and her words are ‘joined in earth’. These two poems seem, therefore, to link Hughes’ vision with both these women who have been of major importance in his life and, since both women were mothers, the poems restate the theme of ‘the mothers’ which runs through the sequence.

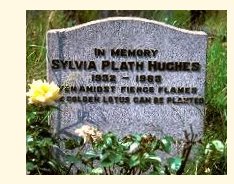

Mother Nature’s words are ‘engraved in rock’ everywhere in Elmet and this is reflected in the poems and the photographs throughout Remains of Elmet, but there are actual words engraved in rock at this place where Hughes’ wife and his mother are buried. Only metaphorically are his mother’s words ‘under his feet’, for on Edith Farrar’s tombstone there are only names and dates7. On that of Sylvia Plath, however, is carved:

Even amidst Fierce Flames

The golden lotus can be planted.

Such words assert, even in Sylvia’s death, the survival of the female life–principle of re–creation and generation which the lotus represents. They can be found in a poem by the Ming Dynasty poet, Wu Ch’eng–en, which is clearly about alchemy and regeneration, (The Adventures of Monkey translated by Arthur Waley, Ch.2). And, whether or not these are the words to which Hughes refers in ‘The Angel’, this final poem in Remains of Elmet brings together the human mothers and the Mother Goddess, whose triple aspects of Bride, Mother and Layer–out Hughes has elsewhere described as the different faces of the Angel of Death, who is also the Angel of Life8. The mothers and the angel, therefore, are symbolically linked by the powerful life/death force of which they are the instruments.

In interpreting ‘The Angel’ as an affirmation of the power of Mother Nature’s destructive and creative energies on Earth, the transforming and healing influences of Hughes’ own work during the years between the writing of the two dream/omen poems must be considered. Of particular importance in interpreting the final stanza of ‘The Angel’ is a sequence of seventeen poems which were published in a limited edition by The Rainbow Press in November 1979, just seven months after publication of the limited edition of Remains of Elmet. Adam and the Sacred Nine deals, once again, with the question of human nature, of the search for meaning, and for understanding of our place in the world9. It documents Adam’s ambitious dreams, his insignificance, his defeat, his visitation by ‘sacred’ emissaries of Nature, and, ultimately, the beginning of self–knowledge. Its significance here lies not so much in Hughes’ exploration of Adam’s state, as in his ultimate understanding of it and the means by which he expresses this. Through “The sole of a foot / Pressed to world–rock” (THCP.451–2) ( a traditional symbolic route of enlightenment) Adam, reborn from the sacrificial flames of the Phoenix, wakes to the knowledge of his total unity with Nature. Adam, who was made of earth, is also made for earth:

I am no wing

To tread emptiness.

I was made

For You.

Mother Nature, through her birds, has taught him this, and she now affirms her teaching through the rock on which he stands. So, his mother’s words, as in ‘The Angel’, are under his feet.

The importance of this revelation, and the symbolic relevance of ‘The Angel’ to the whole of the Elmet sequence, lies in the warning which both contain for us: it is a warning of Nature’s inevitable resurgence and of the destruction of any society which tries to control and suppress her energies in the way that the Elmet people did. Despite the personal context of Hughes’ vision, his message is universal and it is similar in many ways to the visions of others who have foreseen the end of the world.

Hughes’ Angel of Death, who is also the Angel of Life, has well known parallels in the Bible books of ‘Ezekiel‘ and ‘The Revelation’, as well as in the Koran and in Jewish Kabala. Its appearance, like that of Ezekiel’s huge and brilliant heavenly messengers, was heralded by a fiery elemental disturbance; and just as Ezekiel’s angels “sparkled like the colour of burnished brass”, Hughes’ angel’s massive awesome beauty “was cast in burning metal”. It heralded news of destruction and salvation, as does ‘the Crier’ who appears when “the moon is cleft in two” at the “Hour of Doom” in the Koran10; and as do the various angels in the ‘The Revelation of St John the Divine’.

In both the Bible and the Koran, the forecast destruction precedes the Day of Judgment when “a new heaven and a new earth” will be created11, the imprisoned human Soul will be released, and unbelievers will be “cast into the Fire”12 Their angels are male, their Heaven and Earth belong to a male god, and it is he who judges, destroys, and promises salvation. Hughes’ angel, however, is female and she is associated with all that is symbolically female – the moon and the snow, valleys and moors – and with Earth rather than Heaven. She comes from the dark valley and disappears “Under the moor”; and she promises no resurrection but that achieved through Nature, of which we are all a part. Hughes’ conception of the universe is pre–Biblical, he places humanity within the framework of the ancient beliefs on which the Judeic–Graeco–Christian religions were founded and in which the subtle female spirit of Nature predominates. For him, Mother Nature’s energies are part of ‘The Infinite’: part of a vast, supreme unity which is, at once, everything and nothing. From this ‘One’, as in Hermetic lore, the physical world emanates, and we are its reflection in miniature.

Yet, our sins and our salvation are in our own provenance. We share in these Universal Energies, and must learn to live in harmony with them; and our guide to this is the divine faculty – the ‘luminous spirit’ within us. In his essay on ‘Myth and Education’, Hughes wrote that it is the divine faculty which unites our inner and outer worlds: without this faculty the inner world “is a place of demons” and “the outer world … a place of meaningless objects and machines”(WP.151); without it “humanity cannot really exist” (WP.149). For Hughes, as for Blake, the divine faculty is imagination “which embraces both outer and inner worlds in a creative spirit”(WP.149).

Through our imagination, Hughes seeks to teach us that Nature, our creator and destroyer, may also be the instrument of our enlightenment. We are perpetually subject to her powers: and a Culture which misunderstands, suppresses or ignores Nature and regards the Earth as “a heap of raw materials given to Man by God for his exclusive profit and use” becomes, as Hughes wrote in his review of Max Nicholson’s book, The Environmental Revolution in 1970, “an evolutionary error”, because “Nature’s obsession, after all, is to survive”13. Nature will fight back and attempt to restore the balance; therefore, our only hope is to become aware of our true relationship with Nature and to learn to live in harmony with her.

As well as reflecting the hermetic principle of ‘As above so below’, Hughes’ conception of the world as a single organism, each individual element of which is an essential part of a balanced unity, resembles the Chinese Taoist conception of the Universal Energies as a balance of Yin and Yang. Both resemble the Gaia hypothesis which is fundamental to ecological science and which was first propounded by James Hutton (a contemporary of William Blake) before the Royal Society of Edinburgh in the eighteenth century. It regards the Earth as a living organism which will adapt itself to physical changes in such a way that balance and life is maintained, because, as James Lovelock wrote in his revival of this hypothesis, “living organisms have always, and actively, kept their planet fit for life”14.

In his imaginative attempts to teach us this, Hughes described one historical period of retribution in his Introduction and Note for A Choice of Shakespeare’s Verse (Faber 1971). There, he cited the bloody, religious war which took place when Puritanism enforced suppression of the Old Goddess and the old acceptance of the natural energies. He also wrote frequently of our own society as being “exiled from nature”15 and to this he attributed the world’s current ills, execrating “The Scientific Spirit”, this “master of ours” which suppresses the instinctive and imaginative energies, and which was

born of the common hunt for the nourishing morsel, nursed by the benign search for objective truth, schooled in the pedagogic idolatry of the objective fact, graduated through old–maid specialised research, losing eyes, ears, smell, taste, touch, nerves and blood, adapting to the sensibility of electronic gadgets and the argument of numbers, to become a machine of senility, a pseudo–automaton in the House of the Mathematical Absolute. So it ousts humanity from man and he dedicates his life to the laws of the electron in vacuo, a literal self–sacrifice, and soon, by bigotry and the especially rabid evangelism of the inhuman, a literal world–sacrifice, as we all too truly now fear16.

Having such vehement and long standing beliefs in the destructive power of thwarted Nature, it is understandable that Hughes should have regarded his angelic nightmare/vision as an omen with more than personal significance, and that he should present it to his readers as an apocalyptic vision and a warning for humanity in general.

Hughes, like his friend Baskin, shared Blake’s “apocalyptic eye” and a “prophetic concern” for what Blake called “the human form divine”17.And, just as Blake, in Jerusalem, used London and the cities of England to demonstrate his vision of Man’s “passage through/ Eternal Death and the awakening to Eternal Life” (Jer.4:1–2), so, in Remains of Elmet, Hughes used his own small section of England to demonstrate the fulfilment of the angelic portent and to alert us to the danger of our ways. ‘The Angel’ serves as a coda to the Elmet poems and, by its similarity with other apocalyptic visions, it extends the scope of its prophecy to encompass society as a whole.

For permission to quote any part of this document contact Dr Ann Skea at ann@skea.com

Go To Next ChapterReturn to Poetic Quest Homepage

Go to Ted Hughes Homepage for more options