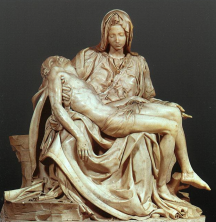

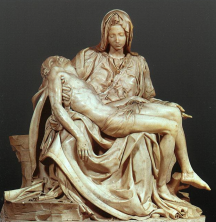

The first image in ‘River’ is that of a pieta, Christ lying across the lap of His mother, as in the Michaelangelo sculpture and other art works. This image of the fallen and risen god (not just a Christan God) continues throughout the poem.

The first image in ‘River’ is that of a pieta, Christ lying across the lap of His mother, as in the Michaelangelo sculpture and other art works. This image of the fallen and risen god (not just a Christan God) continues throughout the poem. RIVER

The Origin and Development of River

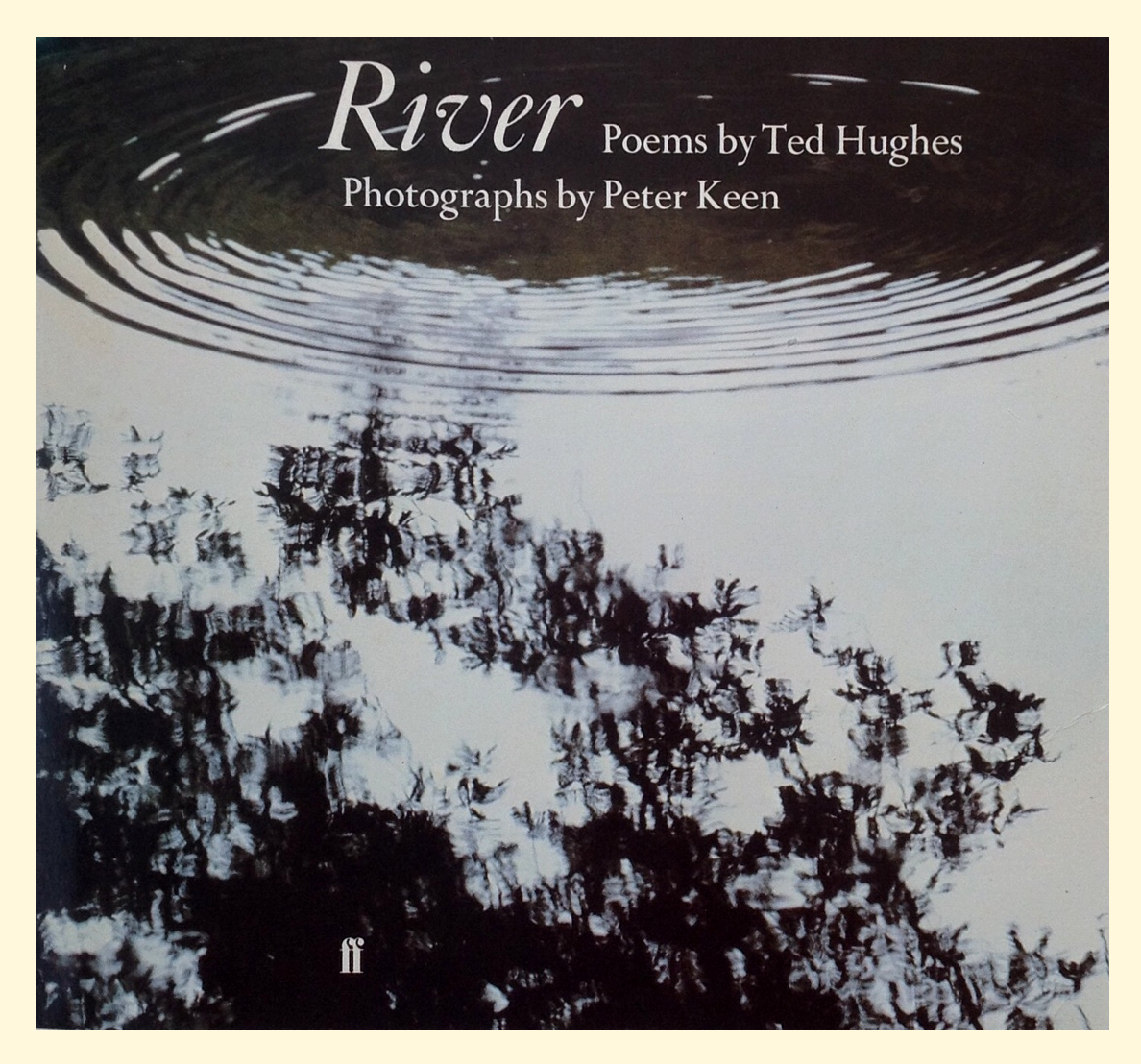

River was a long time in the making. In a document in the British Library, Peter Keen describes the seed of the book as being sown in 1976 when, at Carol Hughes’ suggestion, he and Ted first met in Devon to go fishing together. The two men discovered that they shared a mutual understanding of the sport and this became the beginning of a long–term friendship. Some time later, Peter Keen wrote to Ted suggesting that they collaborate on a book about rivers and the associated wildlife and Ted, after seeing some of Peter’s photography, liked the idea and agreed. As Peter remembered it, they were to be co–authors, each making their own separate contribution: Ted not reflecting Peter’s photography and Peter not illustrating Ted’s work.

In April 1978, Olwyn Hughes, acting as their agent, began negotiations with the publishers David & Charles. The intention was to produce “a really handsome book, a kind of collector’s piece” with possibly a small, signed edition alongside a normal trade edition. By July, there was talk of Ted and Peter producing enough text and pictures to create a dummy book to show at the Frankfurt Book Fair later that year.

By August, negotiations with David & Charles had stalled over a dispute about the handling of American rights, and the possibility of Faber taking on the book was raised.

From 1979 until September 1982, negotiations with various publishers continued, the main difficulty being the cost of producing a beautiful book with first–class paper and the best colour reproductions. Meanwhile, Ted was writing poems but Peter was slow in providing Olwyn with photographs to show to the publishers. In early July 1979, it was suggested that River poems and photographs might be included in an exhibition of Ted’s illustrated work to be held at the Victoria & Albert Museum in London in September/October. Just two photographs by Peter Keen were included in the exhibition, ‘Sea Trout Rising’ and ‘Trout Reflection’, together with a note that they were for a projected book of poems and photographs provisionally called ‘River’.

That same year, the idea had been floated that Nicholas Hughes should create a dummy book, with prints, on his newly acquired Albion press. However, it was not until April 1981 that he produced limited editions broadsheets of three of Ted’s River poems: ‘Catadrome’, ‘Caddis’ and ‘Visitation’, each illustrated with drawings by Ted.

By April 1980, Ted was writing to Keith Sagar that the text for the book was “finished more or less” (P&C 91), although he later wrote that the River poems were “still oozing along” (P&C 113); and in October 1982 he was still “writing and rewriting them” (P&C 120).

By May 1981, James McGibbon, who had been handling negotiation at David & Charles but had since moved to the publishers, James & James, had picked out twenty–one photographs from which transparencies had been made and a dummy book has been sent to several publishers. One had also been sent to Shell and the British Gas Company with a view to obtaining sponsorship from them. The initial response from Shell was based on the idea that the book might be a subtle way for them to demonstrate their concern for the environment. They suggested that they would require 2–3 pictures clearly demonstrating this, and that the title must be The Shell Book of the River. They also wanted a children’s poetry competition linked to the book, and a special edition for school libraries. What they really wanted, as McGibbon noted, was prestige and a clear commercial image.

By September 1981, Faber were talking about a trade edition of the book with just a few pictures. The Observer, on the other hand, had expressed an interest in producing “a splurge edition” with magnificent photographs and “simply text”. As Ted described it to Keith Sagar (P&C 95), it was to be “Not a coffee table book, but an ambassador’s gift. Hugely expensive” – a book in which “nobody, who’s going to buy the book, is going to read my verses. They could as well be Middle–Kingdom curses, in the original. They’re just decorated with a respectable aura”.

The Observer book did not eventuate but by January 1982 Faber were expressing real interest, provided a sponsor could be found; and by September that year agreement had been reached with the British Gas Corporation and a joint publication by Faber & Faber and James & James had been decided. British Gas was to select the cover photograph and to add a note making a point about their re–landscaping following the installation of underground gas pipes. They also stipulated that the book should not be more expensive than the market was used to.

The contract which was drawn up with Faber divided royalties in their customary manner for illustrated books: 75% for the text, 25% for the photographs.

At this stage, Peter Keen, who believed that he and Ted had originally agreed to a 50/50 division of royalties, objected to the contract. The situation, as Ted said when discussing River with me in 1995, and as he wrote to Keith Sagar in 1982 (P&C 123), had become “delicate”. Olwyn Hughes, in her capacity as agent for both Ted and Peter, was in an awkward position. She wrote to Peter that Ted had no memory of a 50/50 agreement, and that the book would sell on Ted’s name and his usual market. She pointed out that Faber decided the percentages and that even with such a famous artist as Baskin, the division was 75% for text and 25% for pictures; also that Faber advised that the only adjustable figure was Ted’s. Ultimately, Ted asked Olwyn to negotiate a 60/40 division of royalties and this was agreed.

Disappointed, and still feeling aggrieved, Peter dispensed with Olwyn’s services as his agent. In 2004, he wrote his own account of the way the book came into being at his suggestion, his memory of the agreement to co–author, and how he had always considered the book as a joint enterprise in which he and Ted each concentrated on their own individual talents. He deposited this account in the British Library.

In September 1983, River was published by Faber & Faber in association with James & James. It was produced in both hard–back (2,500 copies) and paper–back (15,000 copies) editions. Inside the front of the book, on the page which contains the publishing details, are the following notes:

[Under the Countryside Commission logo]

“The Countryside Commission is concerned to conserve and enhance the natural beauty and amenity of the countryside; and to secure public access for open–air recreation. The Commission replaced and assumed the function of the National Parks Commission when the Countryside Act became law in 1968.”

[Under the British Gas logo]

“The British Gas Company has to ‘develop and maintain an efficient, co-ordinated and economical system of gas supply’. Because the Corporation's major investment is in underground pipelines and rural installations, it has to achieve this primary objective with care, taking into account legislation such as the Countryside Act under which it must have regard to the desirability of conserving the natural beauty and amenity of the countryside.

Over many years, British Gas has developed a very positive attitude to conserving the natural environment, and this policy has created an atmosphere of trust among those responsible for planning in local authorities and in the communities affected. As a result British Gas has been able to introduce a gas supply system which now carries well over one third of the heat energy used in Britain. This has been built over the past twenty years with only minor impact on the countryside”.

On the back of the first paperback edition is the following blurb:

“This book contains and records the manifold richness which lies behind a single word – River. Two anglers, who also happen to be a great poet and a superb photographer, have pooled their resources to commemorate the eel, the otter, the trout, the stripping of salmon, the kingfisher, the heron, the cormorant, and, finally, the moving universal implications of river life. Ted Hughes’s poems have all the precision of photographs: “the water-skeeter on its abacus”. Peter Keen’s photographs have all the precision of poetry. River lives in the mind like a watermark – stamped indelibly by two enormous and complementary talents. ‘Published with the assistance of British Gas and the Coutryside Commission’”.

The book is dedicated to Ted’s son, Nicholas (who was also a fisherman) and Nicholas’s partner Andrea.

As a footnote to the whole exercise, Ted wrote to Keith Sagar (P&C 126) “I’ve made some bad mistakes, grafting myself onto others…. I’ve finished with these huge tomes that won’t go on a shelf & that booksellers hate & refuse to give room to after the first honeymoon. Remains of Elmet and Cave Birds have become like the Okapi in the 19th century to be found only in native legends and Hunter’s memoirs”.

In 1984, River was published by Harper and Row in the United States. This edition contained no photographs. The same poems were included as in the British edition but in a different order.

A detailed analysis of the River poems can be found in Skea, A. The Poetic Quest (University of New England, Australia, 1994).

My thanks to Olwyn Hughes for permission to quote from her River correspondence, which is now held in the British Library (Add.88615)

An introduction by Simon Armitage to a letter and maps sent by Ted Hughes to Peter Keen (together with images of the letter and maps)was published in the magazine Granta in June 2012 and is now available on-line. Sagar/Tabor Bibliography Supplement: Granta 26June 2012 C529

P & C = Sagar, K. Poet and Critic, British Library, 2012.

“I am a Geography teacher who has for many years taught pupils about rivers. I plan to introduce some of Ted Hughes’ River but some of the ideas and imagery may be difficult for the age range (Year 7. 11 years old). The two poems I have in mind are ‘The Kingfisher’ (THCP 662) and ‘River’ (THCP 664), and I am very interested in the cycle or hydrological cycle implied within ‘River’. I understand most of the references with the exception of:

Through him, God / Marries a pit /Of fishy mire

and

…Broken by the world. / …In dumbness uttering spirit brightness / …Scattered… / After swallowing death and the pit.

I would be grateful for some advice or simple analysis. I notice that in both poems he refers to a pit. I am not sure if that is a connection or not. ”

Hughes was passionate about the health of rivers, and he saw the degradation which was taking place due to agricultural run–off and other pollution. He wrote letters to the media and to members of parliament about this, but there is nothing of that in River. There, he saw rivers as the source of life and linked them with the Mother Goddess and creation, and he re–created the life in and around rives in the animals and flowers associated with them. He also referred to myths and legends, especially the Celtic myths about the Salmon which, in Irish myth (for example), swam in Connla's Well and gained Wisdom and Knowldge by eating nuts which fell into the well from the Nine Sacred Hazels Trees which surrounded it.

Your students might enjoy hearing about Fionn MacCumhaill (Finn McCool), who was a pupil of the Druid poet Finn Eces. Finn Eces caught a sacred salmon and was cooking it up in a soup which he left young Finn to look after. Finn dipped his thumb in the soup, which scalded him, so he put his thumb in his mouth to cool it. Thus, he acquired the knowledge, foresight and wisdom of the salmon and grew up to be a hero. In the Welsh Mabionigian, too, the Salmon is regarded as the oldest and wisest of animals.

Hughes recreates the life of the salmon, firstly in the men milking it for milt in ‘That Morning Before Christmas’ (THCP 639), then following its journey until its ‘marriage’ in ‘September Salmon’ (THCP 673, its death in ‘October Salmon’ (THCP 677) and it rebirth in the final poem ‘Salmon Eggs’ (THCP 680). For him this ‘sacred’ fish is an indication of the life and health of the river.

With regard to the quotations you mention:

The first image in ‘River’ is that of a pieta, Christ lying across the lap of His mother, as in the Michaelangelo sculpture and other art works. This image of the fallen and risen god (not just a Christan God) continues throughout the poem.

The first image in ‘River’ is that of a pieta, Christ lying across the lap of His mother, as in the Michaelangelo sculpture and other art works. This image of the fallen and risen god (not just a Christan God) continues throughout the poem.

In Christian teachings, Christ (representing the word of God in our world) was broken by the world just as the pure waters of the river, the source of life, are broken by human intervention (diverted, channeled and, especially, polluted). They too lie across the lap of the Mother – Mother Earth – and they, too, come from heaven, silently, dumbly, in the form of rain. Maybe, too, it was Christ’s actions – his sacrifice – which spoke louder than words.

The brightness of this river/god is scattered everywhere by light but also buried – in caverns, in the earth itself – in dry tombs, even. And the dry tombs may literally be dry tombs but, in the extended metaphor of the poem, they also represent the spiritless world of matter, the human world which, in religious teachings, “at the rending of the veil” will be enlightened to the spiritual mysteries.That rending of the veil also literally describes lightning rending the clouds and bringing delivery from dryness and drought – bringing life–giving water, so that the seeds may flourish.

The river waters, too, swallow death, swallow dead animals and plants, and help the disintegration of matter which precedes recycling and renewal: Just as the god, not just in Christan teachings but also in many mythologies, dies and rises again bringing new life and fertility to the world. In Norse mythology the god, Odin, who governs war, death, poetry and wisdom, is sacrificed, upside–down, from the World Tree in order to obtain enlightenment (knowledge of the runes and foresight). The river, too, “hangs by the heels”: it runs headlong until it is restrained by its heels at “the door of a dam”, where we can see it hanging but where, in the dam, it may also sacrifice some of its energy for the material needs of the world (electricity, for example).

Yes, in both poems the pit does suggest the pit of Hell and the pit of death, the pits in which human remains are buried, but in ‘River’ it is also the dry, spiritless, pit of the material world. And the waters of the river, the waters full of spirit and energy, do literally, in the continuous water–cycle of evaporation and precipitation, wash themselves of all deaths and, like all gods, are immortal.

‘The Kingfisher’ is a beautiful evocation of the colour, energy, speed and action of that little bird. Perhaps, all you need for this poem is Hughes’ statement in the original book of What is the Truth that God is there in every living thing. This book is Hughes’ own expression of William Blake's belief that “everything that lives is Holy”.

Sadly, the story in What is the Truth is not reproduced in the Collected Poems, but after everyone has described their idea of what each animal is like, according to their particular view of the world, the fatherly God says : “The Truth is…that I was those Worms…. I was that Fox. Just as I was that Foal. As I am, I am. I am the Foal, I am the Cow. I am the Weasel and the Mouse. The Wood Pigeon and the Partridge. The Goat, the Badger, the Hedgehog, the Hare. Yes, and the Hedgehog's Flea. I am each of these things. The Rat. The Fly. And each of these things is Me. It is. That is the Truth". And the Kingfisher, too, would surely be included.

So, the kingfisher, like a little god, dives into the river – that pit of fishy mire – swallows death (literally, dead fish), but also seems to sacrifice itself – to swallow death – and to emerge from it renewed and as bright and energetic as ever.

In spite of how all this seems, Hughes was not a conventionally religious man. He used the Christian stories partly because they were so well known and, as he said, when a story is well–known single reference is enough to light up a whole story in the mind of the reader: "just as you need to touch a power line with only the tip of a finger" (‘Myth and Education’, WP 139). Maybe that's not as true of the Christan stories now as it used to be.

“Who are the “we” in the poem 'That Morning’ (THCP 209)? Do the salmon represent knowledge and the river imagination?.”

Hughes was a fisherman and he was passionate about fishing. The ‘we’ probably refers to himself and his son, Nicholas, who was working in Alaska and with whom he went on a number of fishing trips. One of these is described in a letter to Barrie Cooke (LTH 15 Sept. 1980): “Bears everywhere”, he says, and he talks about the salmon they caught. The “we” can also refer to us – as if he is bringing us into this glorious turmoil of energies that he is describing, and making us creatures of light, too. This would have been one reason for choosing the poem as the last poem in Selected Poems (1982): he wanted to leave us all embroiled in Nature’s bountiful energies. Hughes believed very strongly in the power of poetry to effect changes on the reader (in just the same way as ritual chants are used in magic). And he wanted to leave us, and himself, in what he called an ‘up-beat’ mood. As he once said: “I have a superstition that the writer, even more than the reader, is affected by the mood and the final resolution of his poem in a final way. In each poem, the writer to some extent finds and fixes an image of his own imagination at that moment. But if a poem concludes in a ‘downbeat’ mood, his imagination is to some degree fixed and confirmed in that mood. In the ordinary way, his imagination would heal itself – move on to new moods. But the poem stands there, permanent, vivid and powerful, and tries to make him continue to live in its image.” (Critical Forum Transcript).

The salmon, in many mythologies, is a symbol of wisdom rather than knowledge. There is a difference: you can know a great many things but still be unwise. In Celtic mythology, the salmon is ‘King of the River’. It is said to eat the nuts which fall into the pool from the Nine Hazel Trees of Poetic Art, thereby imbibing all the wisdom of poetry and science, as well as oracular powers. In the poem, salmon are also beautiful living creatures, full of energy and spirit, and the persona (perhaps not the poet himself) telling us about them is awed by their massed beauty: salmon are heavy, massive fish, and there is a great mass of them in the river.

The river certainly may represent imagination, and a river is often used as a symbol of the interface between the known and the unknown, the conscious and the unconscious. The river is also the watery part of the four elements – air, fire, earth and water -of which all nature is composed: it is part of “the tingling atoms” of the world. A river may also represent the river of life, the steam of energy and time in which we live, and the life-giving waters which are essential to us.

* * * * * * * *

“Why are the bears in ‘That Morning’ called “creatures of light”, do they have some mythological association?”Bears are certainly part of many mythologies around the world. Although bears no longer exist in the wild in England, they were an ancient totem beast. The name of King Arthur, of the Knights of the Round Table myths and legends, derives from ‘arth’, which means bear. And the most important constellation of stars in the sky anywhere in the Northern hemisphere is that of Ursa Major (The Great Bear), which is used by navigators to locate the Pole Star – the fixed point around which the night sky appears to revolve. Ursa Major, because of its shape, is known as ‘The Plough’, ‘The Dipper’ and also ‘Arthur’s Wain’. And the Pole Star itself, which is the axle of the Great Wheel of the Sky, is part of the constellation of Ursa Minor, The Little Bear. Bears, in this sense, are heavenly bodies and creatures of star-light.

Because of the importance of the star constellations of The Great Bear and The Little Bear as markers in the night sky, many myths are associated with them. In Classical Greek mythology, the Goddess Callisto was seduced by Zeus, and when his wife, Athena, found out and turned her into a bear in anger, Zeus placed her in the night sky as the constellation of The Great Bear. Later, the Great Bear became associated with the Mother Goddess. It was also sacred to Artemis and it was one of her disguises.

However, you do not need to know any of this mythology to see that in the poem the bears are beautiful, awe-inspiring creatures, lit by the sun, alight with energy, immersed in Nature and enjoying her bounty. The whole scene is one of abundance, light and beauty, and it is clear that the poet/fisherman feels blessed to be fishing there, beside the bears, sharing the bounty of Nature. Like the bears, the humans are also lit (or animated) by Nature’s energies, so they, too, are creatures of light.

© Ann Skea 2008. For permission to quote any part of this document contact Dr Ann Skea at ann@skea.com