CROW

“I have read that Ted felt that he never finished Crow and that the real intention of the work was not fully realized. It appears that there are many limited editions of Crow poems and I understand that there are numerous drafts of unfinished or abandoned Crow poems in the Emory University Ted Hughes Archive in Atlanta, U.S.A. Do you think that these will ever be collected for publication?”.

The definitive version of Crow does not exist, but all of the published poems appear in Ted Hughes Collected Poems (Faber, 2003). Ted began the Crow project in 1965 (Letter to Keith Sagar, LTH 18 July 1998) and it began to grow into a folk-epic in 1968 (Letters to Leonard Baskin, LTH 2 March 1968, and 16 July 1969; to his brother, Gerald, 27 Oct. 1969; to Daniel Weissbort, Autumn 1969). At the end of 1969, Ted told Leonard Baskin that he had “about 45 poems concerning Crow – so I’m calling it a day, and publishing them” (LTH 15 Dec. 1969). The last Crow poem Ted wrote was ‘A Horrible Religious Error’ (THCP 231), which he completed a week before the deaths of Assia and Shura Wevill. He abandoned Crow. Only with Cave Birds did he begin his quest again, this time from a firmer foundation and reaching a good conclusion.

At poetry readings, Ted often described the Crow ‘story’ in some detail and explained the place of particular poems in that story (see, for example, my transcript of his reading at the Adelaide Festival in March 1976). He did this, too, in letters to Keith Sagar (LTH November 1973 and Robin Skelton (LTH 15 October 1975).

As to the Emory papers, they will keep scholars busy for years to come, and bits and pieces will probably appear from now on.

Ted Hughes wrote a number of letters to Leonard Baskin about the Crow poems. These, and other letters written during their long friendship and collaboration, are held at the British Library

Keith Sagar has a chapter on Crow in his book The Laughter of Foxes (Liverpool University Press, 2000).

* * * * * * * *

“I have chosen to write an essay about ‘Crow’s Theology’ (THCP 227). I was wondering if you could tell me if Ted Hughes was an atheist, and is Crow meant to be an amalgam of man and nature, or is it a guise for Hughes to hide behind as he vents his anger on God?”

Hughes was not so much an atheist as a non-Christian. He certainly had a strong belief in the existence of spiritual energies and their influence on us, but he did not espouse any particular religion. Like William Blake, he thought that many religions distort the Truth with man-made rules and interpretations.

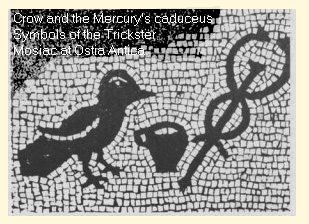

Crow’s God is like the one Blake called ‘Old Nobadaddy’ – a character who is not infallible or omnipotent – a sort of mythical figure apt to make mistakes. If you read what Hughes said about Crow (e.g. in my transcript of a reading at the Adelaide Festival), you will see that he is like the traditional Trickster figures of many folk-stories. I have discussed this in detail in my paper ‘Ted Hughes and Crow’. Trickster stories seem to allowed people to express all the antisocial, rude, socially unacceptable feeling and ideas which normally they have to hide in polite society. Psychologically, Trickster acts as a sort of safety valve for those feelings.

Hughes was using Crow in this way, to release feelings (in the reader as well as the writer) which if suppressed might cause psychological ills and traumas and lead to social ills. Psychology suggests that suppressed feelings lie behind many human problems and that on a larger scale this leads to wars and social upheavals. Hughes agreed with this view.

Hughes’s Father was one of the few survivors from his division of the Lancashire Fusiliers at the Gallipoli landings during first World War, and he went all through the full scale war. Hughes has said that he spent his earliest years contemplating his father’s survival: “He didn’t talk about it at all but it was a big presence on our lives in the Thirties” (Poetry Reading, 1996). Hughes’ childhood was also influenced by the ongoing grief of the many people in his part of Yorkshire who had lost loved ones during that war. Hughes, himself, was a child during World War Two; and later he lived through very real threats of Nuclear war. You should read the poem ‘Out’ (THCP 165). Ted Hughes’ belief in the deep spiritual malaise of our society, and the need for the sort of imaginative healing poetry can offer us by stimulating our imaginations, lies behind nearly all his writing.

Also, in Crow Ted points out some of the problems an unfeeling, soul-less creature can create. Crow is just a crow. He cannot empathize with normal human feelings or understand human concepts of right and wrong. His behaviour is natural crow behaviour, uninfluenced by any human concept of morality; but he is also man-like (anthropomorphized) and has thoughts and ideas, but no soul.

Don’t miss the humour of Crow, either, although it is very black, blunt, irreverent and a-moral humour.

See also my comments on religion and mysticism under Birthday Letters and Cabbala, Mysticism, Shamanism, Sufism, Magic.

* * * * * * * *

“I have a question concerning Ted Hughes poem ‘Lovesong’ (THCP 255). Did he write it in as the answer Sylvia Plath’s unpublished poem, ‘Mad Girl´s Lovesong’?”.

Ted’s poem was not related to Sylvia’s in any significant way other than that they both happened to be about love.

‘Lovesong’, was first published in The Northwest Review in 1967 as ‘second Bedtime Story’. It was published several times in different places before being collected in Crow as ‘Lovesong’. It was part of the sequence of poems which Ted wrote about Crow, his curious, soul-less, amoral bird who began, as Hughes said, as “God’s nightmare” ( Adelaide Festival transcript) and who wanted to become human.

Crow is not immoral or knowingly cruel: he is a-moral (morality is not part of his world) and displays all the atavistic characteristics of the crow species. His experiments, as he tries to learn to become human, often go terribly wrong. Crow has particular difficulty in relating to the female elements of nature (his nature and Nature). At one stage on his questing journey he meets an old woman who questions him. One question is “who paid most, him or her?” – ‘Lovesong’ is an answer to that question.

Crow needs to learn about love, but his first attempts, like the love in ‘Lovesong’, are wholly selfish. Love, in this poem, is depicted as a devouring need to own the other person. All that achieves is to destroy the other person by making them identical to oneself. True human love, on the other hand, requires sharing and balance and thought for the other.

Another related question asked by the old woman is “Was it an animal? Was it a bird? Was it an insect? Was it a fish?”. The Crow poem, ‘The Lovepet’ (THCP 550) is an answer to this question. It shows some progress in Crow’s learning about love but the Lovepet still seems to be something outside these two people – something demanding and separate from them. The poem in which love is depicted as truly sharing and creative and beautiful is ‘Bride and Groom lie Hidden for Three Days’ (THCP 437). This is also a Crow poem, although it was published as part of the Cave Birds sequence.

Sylvia’s poem is not easy to find, although occasionally someone breaches copyright and puts it on the internet. When you read the poem, you will see that it is quite different to Ted’s poem and does not deal with love in the same way at all. Sylvia wrote it for an early boyfriend, Myron Lotz, in 1953 (Stevenson, Bitter Fame, Viking 1989. p.55). She chose not to include the poem in any of her published collections, so I think it can be assumed that she did not regard it as an important poem, more of an early exercise in Villanelle form.

* * * * * * * *

NOTES

‘Crow Goes Hunting’ (THCP 236). This poem is a wonderful ritual evocation of the hare, which is one form of the Goddess. In its form, it is rather like the circular ritual of the poem ‘Amulet’ (THCP 260). It deals with the power of words, and it releases and contains the energies of the shape-shifting Goddess who is, also, the Goddess of poetic inspiration. Crow’s struggles with words reflect a poet’s difficulties in controlling the words which the Goddess inspires. Crow, in the end, is left speechless with awe and admiration – a common condition of poets in thrall to the Goddess.

‘Crow Alights’ (THCP 220). I see this poem in terms of the combined beauty and horror of creation, which inspires both awe and horror in Crow. This is Crow’s “hallucination of the horror”: a vision of a fixed, soul-less and desecrated human world. This is the world which Crow, who cannot express love and who does not know beauty, inhabits. It is a soul-less, bleak, solitary world; a world of boredom and angst. This is not necessarily the way the world is, but the way it might be if truth is not recognized and love is not learned. Nothing, here, escapes Crow, but there is also a hint of double meaning in the final, bracketed phrase: “Nothing could escape”, because Crow would not allow it to do so; but also ‘Nothing’(which is the void from which all creation came, and the wholeness at the Divine Source) could (given the right conditions) escape.

‘Crow’s Elephant Totem Song’ (THCP 238). The ‘Elephant Totem Song’ is a poem about false gods. It is a parable of those false totems which are set up by creatures who do not see beyond the myth they create to the reality it represents. It is about those who want something for themselves and distort the truth, taking pieces of it and progressively turning something of beauty into something ugly. The hyenas (like many humans) saw what they wanted to see in the beginning and created a God, but they were wrong. They distorted the truth about the elephant and recreated it as something dreadful, “wicked and wise”, which they called “beautiful”. So, the elephant was demonized (and only humans anthropomorphize and demonize animals) whilst the true elephant, “deep in the forest-maze” of myth woven by the hyenas, remains forever hopeful of finding the lost “star of deathless and painless peace”.

Matthew Barker offers a different interpretation of ‘Crow’s Elephant Totem Song’:

Hughes’ poetry is about finding the right courage in life to become inhuman. That is, we must move beyond our moral concept of life and what being human is in an effort try to rediscover life in terms of its multi–various forms, without the benefit of illusions. With Crow’s “super ugly” language, Hughes supersedes Romanticism and introduces readers to a new revelation about what life is and what it may mean through its diverse range of forms, which Crow, in his own way, struggles to comprehend. The language is exceptional for its violent clanging of sounds, its clashing of seemingly incongruous phenomena, the jarring rhythms and discordant rhyme, which suggests the struggle man has in coming to terms with the reality of life in its totality.

All this I find in Crow’s Elephant Totem Song’. As much as I like your interpretation, I see something different in this poem. I don’t think Hughes really cared for whether people believed in false Gods. This is not the preoccupation of the Crow poems. Crow is attempting to blast all of our beliefs and traditional notions and ideas away, destroy them utterly, shake us awake to what life really is, an eternal conflict between two opposing forces: one of order, the other of chaos. Neither really cares whether man or our amusing Crow exists or whether either succeeds in the conquest of life.

So on this premise, Crow’s Elephant Totem Song’ seems to suggest the fascinating and utterly separate nature of two very different animals – an elephant and a hyena – one terrible, the other peaceful; different in form and purpose but both with their own beauty. It appears that Hughes sees the hyena as a lesser creature than the elephant, who is more noble and closer to God. So the hyenas are envious of the elephant’s lofty, indifferent grace and want a piece of him, they want to discover him by eating him and reconstituting him in their own form. After the terrible devouring, the elephant becomes something else, no longer oblivious to the envy of hyenas, but something terrible, something they fear and cannot understand, because, in their shame and remorse for wrong doing, they remain irredeemably hyenas. Through resurrection after suffering, elephant has an even greater knowledge of the serene, the peaceful and divine, something that nothing else can see, not even the astronomer. © Matthew Barker, Perth, West Australia. My thanks to him for permission top reproduce it here.

© Ann Skea 2014. For permission to quote any part of this document contact Dr Ann Skea at ann@skea.com