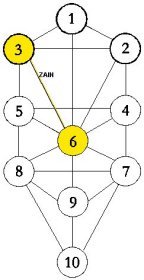

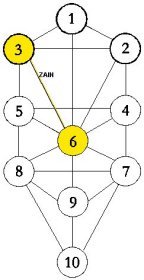

The Path of the Lovers links Tiphereth (Sephira 6), at the heart of the Tree, with Binah (Sephira 3), the seat of the Great Goddess on the Pillar of Form. It is the path on which, symbolically, female and male are brought together in order to create a whole being capable of new, superconscious awareness and able to achieve new spiritual growth. The number of this path is 7, the number of completion in the material world, as it is in the Biblical story of the Creation.

The Tarot number for this path is 6, which is also the number of Tiphereth (The Way, Beauty). This suggests that what is to be learned by those travelling on this path will be an important indication of The Way, which is the one path to spiritual rebirth. And, since 6 is also 2 x 3, the female energies of Binah (Truth, Understanding) on this path are doubly important and all the various powers of the Goddess which were discussed earlier in ‘The Path of the Empress’ are doubly active.

On this Path of the Lovers, journeyers encounter the Divine female energies (those of the Great Goddess of Orphic myth or, in Hebrew Cabbalistic texts1, of the ‘Shabbat Queen’ or ‘Sabbath Bride’), and the power of these to give and to inspire love may enrapture and elevate them to new awareness of their own mystical potential. Appropriately, the Hebrew letter for this path, Zain (meaning ‘sword’ or ‘weapon’) portrays, by its shape, the upward flow of energies - “the return” to the Divine – then the broadening to right and left which encompasses the Divine energies of awe and love. It portrays, too, the double edged potential of the energies on this path, for the sword is a symbol of supreme power and of the binding loyalty which unites its bearer with such power but it is also a weapon of justice, punishment, anger and division.

The astrological sign for this path, Gemini (ruled by Mercury), also represents the binding power of Divine love and the uniting of Divine and human energies. In Greek myth, Castor and Polydeuces were twins whose great love for each other persuaded the Father God, Zeus, to allow them to remain always together as the constellation of Gemini. They also combined Divine and human energies, being the grandsons of Zeus and the sons of Leda, Zeus and the human King,Tyndareus2.

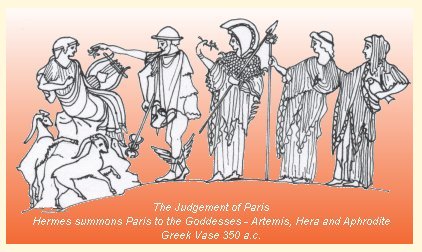

All these aspects of this Path of The Lovers are part of the archetypal Greek myth, ‘The Judgement of Paris’, which is depicted on The Lovers card in traditional Tarot packs.

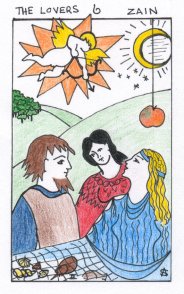

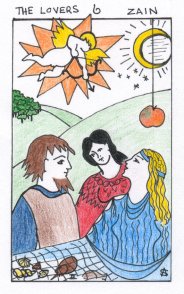

Generally, the traditional cards show four figures: a man embraced by two women, and a winged cherub, with a bow and arrow, hovering above them. The man represents Paris, son of the King of Troy who, because his mother dreamed he would bring ruin to the nation, was abandoned, suckled by a wild boar, and grew up amongst shepherds. The two female figures on the card are two forms of the Great Goddess: Aphrodite / Venus (the amorous Goddess who rose from the sea’s foam and whose magic girdle could make anyone, god or human, fall in love with its wearer), and either Hera (Mother Goddess) or Artemis (Goddess of the Hunt and protectress of children) or a composite of both. The hovering cherub is Eros, Aphrodite’s son by Hermes3, who, inheriting some of his parents’ skills, is able to inspire love between whoever he chooses but is also mischievous and irresponsible.

Classical Greek myth tells how all the gods and goddesses, except Eris (Goddess of Discord), were invited to the wedding of the nereid, Thetis, to the mortal, Peleus. Angry at her exclusion, Eris threw amongst the guests a golden apple inscribed “for the fairest”. Hera, Aphrodite and Artemis each claimed the apple should be hers. They appealed to Zeus for judgement and he, not willing to make the choice, decided that a mortal should settle the matter. Paris was that mortal, and seduced by Aphrodite, who unfairly used the power of her magic girdle and promised him the love of the most beautiful of women, Helen of Troy, Paris chose her and offended Hera and Artemis. In the terrible wars which ensued when Paris abducted Helen from her husband, Menelaus, the slighted Goddesses were avenged.

Both Robert Graves and Joseph Campbell question this telling of the story4. In their interpretations, The Judgement of Paris is not a judgement of the Goddesses, who together represent all female energies and are thus three aspects of the Great Goddess, but of Paris, a mortal who is led to the Goddesses by Hermes, the Guide of the Soul, and who needed to accept the great Goddess in all her forms if he was to obtain the golden apple of immortality and spiritual rebirth. By succumbing to sexual enthrallment and being swayed in his judgement by only one aspect of the Female, Paris fails.

Ted, who wrote of the Great Goddess at length in Shakespeare and The Goddess of Complete Being, would have agreed with Graves and Campbell. He, too, discussed Paris’s relationship with the Great Goddess and (like Graves) identified Helen of Troy with her (SBCB 182-5). But in ‘St. Botolph’s’, the poem on The Lovers path in the Atziluthic World of Archetypes, Ted’s use of the myth is closer to the Classical Greek version. Nevertheless, since Ted regarded Greek myth as “a working anatomy of our psychic life… a whole system of keys and passwords and introductions to energies, and relationships between energies, within ourselves”5, his use of the myth must be regarded as having personal and psychological significance in the Cabbalistic journey he and Sylvia are making in Birthday Letters.

In ‘St. Botolph’s’, Sylvia has all the attributes of the love goddess, Aphrodite / Venus. The waves which surround her may be sound-waves, but her striking looks, the easy sway of her emotions, her vivacity, her intentions (“You meant to knock me out”, Ted writes), all are like those of Aphrodite when she seduced Paris. Even Sylvia’s headscarf, which Ted later found in his pocket, seems like a worldly manifestation of Aphrodite’s magic band which had power over gods and men: “The world lies in its weaving”, Aphrodite told Hera, who once borrowed it in order to seduce Zeus and keep him from his wars, “You won’t return, I know, your mission unfulfilled”. It is significant that Ted makes this headscarf blue in the poem, not red, as Sylvia twice notes in her journal entry for that night (26 Feb. 1958)6 and which would have matched the red shoes Lucas Myers remembers7 her wearing. Blue is the colour of Aphrodite, who is Sea Goddess and Moon Goddess as well as Love Goddess: blue is the colour of the band which Botticelli’s Venus wears in her hair as she rises from the waves.

The colour of Sylvia’s headscarf is not the only discrepancy between Ted’s poetic account of their meeting and Lucas Myers’ memory of the events leading up to it, which he recorded in his book Crow Steered, Bergs Appeared (pp. 29-33) and in Appendix I of Anne Stevenson’s Bitter Fame (Viking, 1989. p. 312). Myers, in ‘St. Botolph’s’, is once again a Hermes / Mercury guide leading Ted to Sylvia as he did in the earlier poem ‘Visit’ (BL 7). “Lucas”, Ted says, “engineered” the meeting: but, as Myers remarks in his own account, it was “Very curious engineering”. He describes how Sylvia approached him, danced with him reciting his poetry, and asked him where Ted Hughes was. “I pointed towards the end of the hall”, he writes, “and she went off. I accomplished this sudden engineering without intending to because I disapproved of Sylvia and didn’t like seeming to put her off Ted”. He did not see the actual meeting, only, next day, the bite marks – the “ring-moat of tooth marks”, as Ted calls it, choosing an image which is suitably watery for a Sea Goddess’s brand.

In the poem, too, unlike the image on the Tarot cards, it is Ted’s girl-friend, tense as “a loaded cross-bow” before Ted meets Sylvia and “hissing rage in the doorway” afterwards, who is given the attributes of the slighted Goddess Artemis, Goddess of the Hunt. In reality, Lucas Myers tells us, this girl-friend was “a sensitive, handsome, light-brown-haired and deep-eyed woman, quite English, quite reserved and the polar opposite of Sylvia” (CSBA 30). Before he met Sylvia, Ted wrote of this other young woman in ‘Fallgrief’s Girlfriends’ (NSP 9) as “a woman of such wit and looks / He can brag of her in any company”. Truly, it would seem, she was a rival Goddess equally worthy of Ted / Paris’s love: and it is as a rival that she appears in Sylvia’s semi-fictionalized account of the party in ’stone Boy With Dolphin’ (JPBD 297-32).

There are yet more ‘mistakes’ in this poem. Writer / Astrologer, Neil Spencer, points out that the astrological information with which Ted begins the poem is not correct for the night of 25 February 19568. He describes two errors which would be immediately obvious to anyone familiar enough with astrological charts to construct one for that night.

To those (like me) who know nothing about serious astrology, the start of this poem is meaningless jargon and not good poetry. But Ted, at the time of writing this poem, was a very experienced astrologer: he would not have made the simple errors which Spencer discerns. Nor, if he was (as I believe) creating the poem as part of his Cabbalistc journey, would he have been careless. The errors, therefore, were deliberate: and I believe that there were two very good reasons for this.

Firstly, Ted’s presentation of the astrological data in ‘St Boltolph’s’ is glib and confident and effectively demonstrates his own carelessness and arrogance with regard to astrological calculations and portents. He was, he says, only a “wait-and-see astrologer”: one who brushed off bad portents with a casual “so what?”, and one who consulted “Prospero’s book” for meaning – a failing he accuses Sylvia of in ‘Horoscope’ (BL 64). He tells us, too, that an expert poet-astronomer like “Our Chaucer” would, unlike him, have heeded the portents, “stayed at home” and made his own calculations, and, “Locating the planets more precisely, / He would have pondered it deeper”. Ted, it is apparent, was still a novice in the magical arts and a Fool at this early stage of his Cabbalistic journey.

Secondly, I believe Ted’s purpose in making these deliberate mistakes was magical.

According to Neil Spencer, the two errors in the astrological details Ted gives in ‘St. Botolph’s’ are as follows:

the night’s Moon / Jupiter conjunction (in Leo) did not oppose Venus (in Aries) but the Sun. Nor is it possible for Venus (in Aries) to be ‘pinned’ to Hughes’s Midheaven if the Sun (in Pisces) is in his tenth house.

But there, in the poem, are Jupiter and the Moon linked to Ted’s natal Sun sign, Leo, bringing “Disastrous expense… Especially for me”, as he says. And there, too, is Venus “pinned exact” on his Midheaven. Thus Ted invokes the powers of Jupiter and Venus at the beginning of this poem in which he sets out to re-create his first meeting with Sylvia. And “suddenly”, in the tipsy, Bacchanalian scene he creates, there is Sylvia, seen in a flash – iconically “unalterable, stilled in the camera’s glare” and “clearer, more real / Than in any of the years in its shadow”9.

My reasons for interpreting Ted’s intentions as magical in this way, stem from his twice repeated use of the phrase “Our Chaucer”, which is redolent with echoes of Renaissance Magus, Marsilio Ficino. Ficino referred often to his revered teacher, Plato, as “Our Plato”10. He also wrote at length about the nature and purpose of divino furore, or divine frenzy, and the way in which music and poetry may express this and imitate the harmony of the Heavens. Through furor, poetry (in particular) can release the Soul buried in matter within each of us so that it may return to the Divine. “[P]oetry springs from divine frenzy, frenzy from the Muses, and the Muses from Jove [Jupiter]”, Ficino writes in a long letter to Peregrino Agli11. He goes on to identify four kinds of Divine frenzy “love, poetry, the mysteries and prophecy” and to note that “According to Plato, Socrates attributes the first kind of frenzy to Venus, the second to the Muses…”.

It is not surprising then that Ted, who was familiar with the work of Ficino and with the concept of furor, should invoke the powers of Jupiter (and his Muses) and of Venus in ‘St. Botolph’s’, thus appropriately uniting the divine frenzies of poetry and love. This, after all, is the path of The Lovers, on which Male and Female energies are united and the Divine spark of love is lit. It is also the path of Zain (the Hebrew letter which, as noted earlier, symbolizes the return to the Divine) and the first path to bring Ted and Sylvia together on their Cabbalistic journey in Birthday Letters. Nor is it surprising that Ted should note that Chaucer, knowing the correct astrological details for that night (as Ted certainly did when he wrote this poem) would have conclude that “the solar system married us / Whether we knew it or not”12.

In the pattern forming World of Briah, the poem ‘Flounders’ (BL 65) offers a metaphor for the possibilities life could have offered Ted and Sylvia. In July 1957, they were, so-to-speak, beached and floundering13: they were newly married, had just arrived in America and were spending a few weeks relaxing in a beachfront cottage at Eastham, Cape Cod, before their teaching jobs began14. Their long-term plans for the future were still uncertain but their commitment to poetry was mutual and of utmost importance.

It was at this time, as Anne Stevenson relates in Bitter Fame (p. 111), that the incident occurred which Ted describes in ‘Flounders’. Ted and Sylvia had set off from Chatham (in an inlet off Nantucket Sound, South of Eastham) in a hired rowing boat. After a few hours of fishing, the tide and the wind changed and they were “dragged seaward”by the strong current. Manoeuvring and luck beached them on a sand-bar, and there they stayed until the skipper of a passing power-boat saw them and towed them to safety.

Again, on this Path of the Lovers, different forms of the Great Goddess appear in the poem and a choice is made. Aphrodite / Venus (“the goddess, the beauty / Who was poetry’s sister”) is clearly there throughout. Sometimes fish-tailed15, always fickle, she plays with Ted and Sylvia who (foolishly perhaps) have committed themselves to a row-boat in her watery world. Ted describes their confident naivety: “our map / Somebody’s optimistic assurance”.

Artemis is there, too. For it is she, sister of Aphrodite, who was Goddess of Poetry before Apollo her twin brother took this role from her.

As a fishing expedition, the day had both good and bad results: as an adventure it was exciting but perilous. Both aspects are apparent in the vivid moods and descriptions of the poem but the question with which Ted begins, “Was that a happy day?”, asks for an objective judgement of the events rather than an emotional response to them. And Ted’s own comment, set in the seven isolated lines which follow this description, puts this so “tiny an adventure”into the context of their marriage and makes it of “monumental”importance in that context.

What does this mean? In what way were these events so monumental in their marriage? Ted’s careful choice of the word ‘monumental’ gives the events of that day iconic significance in the life which he and Sylvia shared and in which marriage meant not only a legal contract, a shared love and linked lives, but also a united dedication to poetry. Appropriately, on this path which in Cabbalistic numerology is Number 7 (completion in the physical world) Ted states their total commitment to this shared purpose: “we / Only did what poetry told us to do”.

Yet, at the time of their arrival in America, there were still judgements and choices to be made – a path to be chosen – and Ted identifies three aspects of the adventure which suggest three elements of Aphrodite’s warning to them about the path they seemed to have chosen.

Firstly, there was the easy option suggested in the “slight

ordeal”which Ted and Sylvia had undergone. They had launched

themselves into the Goddesses world, relied naively on the advice

of others, stayed in “mid-channel”and gone with the flowing

tide.  They had seen others cruise past them

but had been “happy enough”, bobbing along with their lead

weighted lines bouncing along the bottom and a small, poor catch

of “two or three sea-robins”16

to reward them. In many respects, this was exactly what they had

been doing in their lives until that time. They had followed the

paths suggested by parents, teachers and society, and had gained

academic qualifications. But in terms of their own ambitions,

they had, as it were, rowed their own boat (pulled “Northward”,

perhaps towards the North Star, the World-axis of spirit and

destiny); lived meagrely; and written, their work being published

only occasionally17.

They had been happy enough, and now marriage and changing fortune

had brought them to a beach in America.

They had seen others cruise past them

but had been “happy enough”, bobbing along with their lead

weighted lines bouncing along the bottom and a small, poor catch

of “two or three sea-robins”16

to reward them. In many respects, this was exactly what they had

been doing in their lives until that time. They had followed the

paths suggested by parents, teachers and society, and had gained

academic qualifications. But in terms of their own ambitions,

they had, as it were, rowed their own boat (pulled “Northward”,

perhaps towards the North Star, the World-axis of spirit and

destiny); lived meagrely; and written, their work being published

only occasionally17.

They had been happy enough, and now marriage and changing fortune

had brought them to a beach in America.

In real life, as in the poem, “big, good America”would rescue Sylvia and Ted and offer them a taste of financial security and the comfortable affluence which a secure job could bring18. This was the second aspect of the experience Aphrodite offered them that day: a “small thrill-breath of what many live by”; the “easy plenty”suggested by the beach-houses and gardens of the safe “back-channels”where they caught a boat-load of big, tasty flounders.

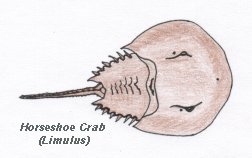

The third aspect of this adventure, “a small prize, a toy

miniature of a life”, is linked symbolically in the poem with the

horse-shoe crab’s carapace which Ted found when they were

stranded on the sand-bar.  The adventure itself, being a result of

fickle winds and tides, falls clearly within Aphrodite’s powers.

The visions she shows Sylvia and Ted are fishy and watery, full

of “marsh-grass / Wild original greenery”, “mud-slicks”, and

“fiddler-crab warrens”. And the tiny “perfect”horse-shoe crab

carapace (honey coloured and bee size and moon-shaped, as suits a

symbol of a Bee Goddess and a Moon Goddess) is also a natural

miniature of “a life”. The horse-shoe crab, in fact, is an

ancient species which occupies an important niche in marine

ecology and supports a world of smaller creatures on and in its

shell as if they were all bonded into “a single

animal”19.

The adventure itself, being a result of

fickle winds and tides, falls clearly within Aphrodite’s powers.

The visions she shows Sylvia and Ted are fishy and watery, full

of “marsh-grass / Wild original greenery”, “mud-slicks”, and

“fiddler-crab warrens”. And the tiny “perfect”horse-shoe crab

carapace (honey coloured and bee size and moon-shaped, as suits a

symbol of a Bee Goddess and a Moon Goddess) is also a natural

miniature of “a life”. The horse-shoe crab, in fact, is an

ancient species which occupies an important niche in marine

ecology and supports a world of smaller creatures on and in its

shell as if they were all bonded into “a single

animal”19.

All these aspects of this tiny adventure are encompassed by the pronoun, “It”, with which Ted begins the final six lines of the poem. So, this “toy miniature of a life”, this “small prize” which became so monumental in their marriage is seen by Ted as a warning which Aphrodite gave to him and Sylvia but which they did not hear. So, they chose Artemis, and this jealous goddess did not tell them of her sister’s warning.

But was it a happy day? Would Ted and Sylvia have been happier if they had had not chosen to do only what poetry told them to do and had not given up their safe jobs and the promise of future comfort to follow that path? There are things in the poem which suggest this may not have been so. The deceptive calm of the inshore waters; the excessiveness of the “surplus”of huge flounders which were caught; the romantic golden glow of the luxurious “play-world” in the summary Ted gives at the end of his description of that day: all hint at the wiles of a fickle goddess anxious to woo the lovers from her sister. And, it must be remembered that what is to be learned on this path is that in order to gain the wholeness of a single animal – of a “single soul” – all aspects of the Great Goddess must be embraced. Sylvia and Ted embraced only one, but to have chosen only the other would, equally, have aroused a jealous goddess’s wrath.

Error and discord in Cabbala are the subject of complex debate. At its simplest, discord is seen as the result of negative energies associated with each Sephira, or as the mask or the empty shell of the positive energies. At its most complex, discord is Evil, ever present in the separate world of demons in the dark Abyss. For all Cabbalists these negative energies (know as Qlippoth or shells) are part of Creation and in some Cabbalistic texts they are seen as the result of an error made during the Creation.

Z’ev ben Shimon Halevi (Adam and the Kabbalistic Tree, Rider, 1978. p. 237) explains disharmony and discord as the shadow side of human nature, and believes that our mistakes and the discord which results from them are a necessary part of spiritual testing in any struggle towards harmony and good. “Nothing is separate in Creation,” he writes, “nothing can operate on its own, because all is One”.

The poem on the Path of The Lovers in The World of Yetzirah is ‘Error’ (BL 122). It expresses not just the sadness of discord and disorder but the mistake of trying to continue the Cabbalistic journey once the “wrong fork” in the path has been taken. The Qlippoth for the Sephiroth joined by this path of Zain (Sephira 6 and Sephira 3) are hollowness and fatalism. And the world which Ted sees as he writes ‘Error’ is a hollow world, a world “in a bubble”, or a thin “transparency” in which the “wedding picture” of his and Sylvia’s new start in Devon looks like a picture on a foreign grave. Nevertheless, beneath the unreality of this scene, “the real bones” – his and Sylvia’s - underwent everything associated with that move, and this path which they “had chosen finally” was, in fact, “aimed at a graveyard”. So, Fate too, is part of the poem.

The doubleness of dream and reality, the hollow and the actual, pervades this poem. Similarly, the phrases for meditation on this path of Zain are double edged: “Twins reconciled” and “The answer of the Oracles is always Death”. Ted and Sylvia were individuals joined by love, like the twins of Gemini, but the discord between them was not reconciled by their move to Devon. And the Goddess who presides over ‘Error’ is not Aphrodite / Venus, who presided over ‘Flounders’, but the jealous Artemis. This chaste Goddess with her hunting weapons is seen more aptly, here, as Nemesis20, carrier of the cut apple bough and the wheel of Fate. In her sodden, gloomy orchard, Ted and Sylvia struggle in the mesh of roots of her stinging nettles. And instead of the Golden Apples of Immortality which they might have gained had Ted chosen their path more wisely, it was Nemesis’s Apple of Discord which grew there.

Devon was, as Ted says in the poem, his “land of totems” but, as always, the images and descriptions in this poem are as real as they are metaphorical. Devon, which produces some of the best cider in England, is often called “the orchard in the West”. But Ted knew, too, that at the Western limits of the Ancient Greeks’ world lay the land of Elysium, abode of the gods and the place in which the Great Goddess’s Golden Apples of Immortality grew. Both he and Sylvia also knew that Devon and Cornwall (still known in England as the Westcountry, as if it is a separate place) were ancient Celtic kingdoms, home of the earliest Britons, steeped in Celtic myth and legend and associated, especially, with romantic lovers. Lancelot and Guinivere, Tristan (Prince of Lyonnesse) and Isolt: all played out part of their stories here. All lived, and still live (as Ted and Sylvia do in this poem) in a land which is both real and unreal – a mythical dreamland, the “Never-never land” of story, but identified with Devon and Cornwall.

Both Ted and Sylvia (in her poem ‘Lyonnesse’ (SPCP 232-3)) identify the Devon area to which they moved in September 1961 with Lyonnesse, the sunken Celtic Kindom which, as legend tells, now lies beneath the sea off the coast of Cornwall. In Sylvia’s poem, Lyonnesse is a lost dream: a sunken Heaven in which people continue to live as they always lived, with “the same faces / The same places”, but forgotten by God. Perhaps Devon did seems like this to her, and certainly she and Ted dreamed of a new start when they made their move. But, as in her poem, their dream did not turn out as expected.

In ‘Error’, too, Sylvia and Ted live like dreamers. Remembering it, Ted sees the move as his choice, and a mistake. Sylvia “sleepwalked” with him, “gallant and desperate and hopeful”, whilst he “wrestled” with the responsibilities and the material necessities of the move, dealing with “the blankets, the caul and the cord” of a new beginning, just as he actually did when Nicholas was born in January 1962. But already it was too late.

Already they had lost the Italian sun. They had given up their planned trip to Italy, which was part of the requirements of the Somerset Maughan Award which Ted had won in March 196021; they had lost the bright sun of their early love which was like the Italian Renaissance sun which shines so brightly on the traditional Tarot card of The Lovers; and, having taken this “wrong fork” to a “dead-end” in a “red-soil tunnel”, they had lost the sun of Wisdom which lights the Cabbalistic path.

And already, Sylvia was in “The labyrinth”: the phrase is set importantly on its own in lines where Ted imagines Sylvia’s own, Devonian Lyonnesse, with its “brambly burrow lanes”, “stump-wart” women, huddled cattle and hills, and a “dark-age dialect”22. This was where “The world” ended: again the phrase is isolated, and the capital on ‘The’ gives it emphasis. But which world? Probably the same three worlds which were linked to the lost Italian sun: the real world of their marriage, the dream world of its Devon renaissance and their shared, Cabbalistic, healing world of poetry.

The “dead-end, crushing halt”, which Ted describes earlier in ‘Error’, echoes the title of a poem which Sylvia wrote shortly before ‘Lyonnesse’. ‘Stopped Dead’ (SPCP 230) is a poem full of anger and bitterness, possibly linked to an incident in which Sylvia ran her car off the road in what she later suggested was a suicide attempt23. Was she testing “the limits”, perhaps, like the bellow in the oak woods in ‘Error’, which suggests that the bull-god / Thor / Otto was still around. Certainly she was testing the limits in her poetry and the anger she had learned to express in her search for Otto was in many of her poems at that time.

In Devon, Sylvia was no longer an American goddess: a goddess of the New World24. She had stripped off that royal “garment” and was “soul-naked” and at her most vulnerable. Her journal notes for those months in Devon show just how hard she tried to be part of the local community, but they show, also, the cold scrutiny with which she observed her neighbours and an acid, biting sarcasm, especially in her jealous comments about Nicola Tyrer.

Ted’s poem, too, continues to be ambivalent. He connects the testing bellow in the oak-woods with “the boots” and the “throbbing gutter”, which are real enough images of a rain-soaked Devon world but which also find echoes in Sylvia’s poems: ‘Daddy’ (SPCP 222-4), and ‘Getting There’ (SPCP 247-9), for example. At the same time, he writes that “ A thin squandering of blood-water - / searched for the river and the sea”, as if the few poems of natural beauty, such as ‘The Night Dances’ (SPCP 249-50), were a frail lifeline of healing love by which Sylvia tried to return to Aphrodite / Venus’s watery realms.

In the end, however, this was what they both “had chosen finally”. A world of discord – “a desolation” in which jealousy and anger outweighed love. This was error.

In October 1961, Sylvia had signed a contract with Heinemann for the publication of The Bell Jar but in November, when she heard that she had been awarded a Saxton Grant for prose writing, she postponed publication for a year so that she could submit the manuscript as work she was doing for this grant25. She was well aware that many people would recognize themselves in her novel and would be upset at her characteization of them; and the portrait of her heroine’s mother was particularly cruel to Aurelia Plath. In letters to her brother and to Aurelia, Sylvia dismissed the book as “a pot-boiler”, adding that it was “a secret” which “no-one must read” (SPLH 16, 25 Oct.; 29 Nov. 1962). Yet, Ted has noted that she wrote the book “at high speed and in great exhilaration” (WP 185); and in August 1961 she sounded jubilant when she recorded her completion of it (SPJ Note 438. p. 696). Her true estimation of the book is, I think, suggested by the pseudonym under which she chose to publish it: Victoria Lucas (‘Victory’ and ‘Light’)26, and by the fact that in 1962 she did offer it to two American publishers, Knopf and Harper & Row, both of whom rejected it.

Sylvia’s decision to publish The Bell Jar is the background to ‘Costly Speech’ (BL 170), the poem on the path of Zain in the material World of Assiah.

At the start of the poem is the Moon Goddess in all her forms. As the full moon, she is Binah, Aima, the Great Mother of All, shining between the Manhattan skyscrapers, rather as Lady Liberty’s torch of Enlightenment shines across the waters just off the Manhattan shore. As the new moon, in “her whole family of phases”, she is the lover and the crone. She is Aphrodite, Venus, Persephone – all the goddesses of passionate love, and the Beauty of Tiphereth: and she is Nemesis, Hecate, Kali – all the goddesses associated with death. “Rising and falling”, the Moon is there throughout life and runs like a gleam “on the rails” through all human endeavours. And, just as the energies of Tiphereth are linked to every path of the Cabbalistic Tree, so the energies of the Moon and the Goddess affect all living things. All Nature responds to her, and Ted invokes her powers to preside over this poem.

Binah (Sephira 3, towards which the journeyer travels on the path of Zain) is associated with boundaries and limits. Sylvia, in 1961 and 1962, was already testing limits in all her writing. But when she chose to publish The Bell Jar, she not only overstepped the limits of conventional ideas of love and morality, she also acted like a goddess, creating and destroying, believing that her word (and human laws) could keep her secret and that she could control the chaos she knew the book could seed in the lives of others. This was tempting and challenging Fate.

The ‘Spiritual Experience’ of Binah, from which the Cabbalist must learn, is the ‘Vision of Sorrow’ and this was the vision Ted saw and captured in ‘Error’. It would be seen again in the results of Sylvia’s choice.

The ‘Virtue’ of Binah is silence, and that is what Sylvia chose to reject. Ariel, as Ted noted “is dramatic speech of a kind” (WP 175), so, too, is The Bell Jar: and words are powerful weapons. When Sylvia’s words did become public, and especially when The Bell Jar was published in America, the results were costly: and not to Sylvia alone.

Tiphereth (Sephira 6 – from which the traveller on Zain journeys towards Binah) also has negative energies. The ‘Vice’ of Tiphereth is self-importance – focus on self. Sylvia’s failing was to let ambition and self-confidence outweigh love and compassion. Everything about love forbids that.

In ‘Costly Speech’, the things which Ted picks out as enforcing this veto are very personal and some, perhaps, could not be fully understood by anyone but Sylvia and himself. What, for example, are readers to make of the Sylvia’s son “doing something strange in a glide of the Deshka”, unless they know that Nicholas is a marine biologist who works in Alaska, where he feels comfortably distanced from all the attention focussed on his family? And what did Ted mean by the phrase which is associated with the “adamant” veto of Yosemite: “onto your daughter’s page, with signatures”? Perhaps he was thinking of the signatures which were stolen from books which Sylvia had given to him (thefts which again show selfishness outweighing natural compassion) and which he later gave to Frieda and Nicholas. Frieda’s poem, ‘The Signature’, describes these thefts, and she also spoke of them in an interview with Libby Purves in December 199927. Although the meaning of these phrases may not be clear, it is very clear that every image from line 6 to line 27 is associated with the New World, and each one of these images links Nature with Sylvia and with her family. In these lines, past, present and future; water, earth, fire and air; family and love - everything associated with The Goddess forbids Sylvia’s costly speech.

In this lowest World of Assiah, however, where darkness and the demons of the Abyss are very close and very powerful, such simple natural “guards” as love and concern for one’s family may not be enough. There is a hint of demonic interference in Ted’s suggests that a “spooky chemistry” was at work in the editors whose opportunism saw the loophole in American copyright laws which precipitated the American publication of The Bell Jar. And he is clear that it was Sylvia’s own “dead fingers” which unpicked the legal locks which allowed this to happen.

Yet, this action of Sylvia’s was not necessarily an intervention from beyond the grave. For, although the events which led up to the publication of The Bell Jar in America did not begin until after Sylvia’s death, this poem shows her, even as she was alive and writing, as half “mortified”. And, in reality, this seems to have been true. Half of Sylvia did seem to be dead to the pain she might cause others by publishing prose and poems about real events and real people. Yet, half of her was concerned enough to try and keep The Bell Jar secret. And whilst half of her, especially as the persona she adopted in some of her poems, smiled with malicious and vindictive glee as she attacked family and friends, half of her smiled with pleasure at the creative achievement of her new voice.

In the end, as in the final line of this poem, it was Sylvia’s choice, and her choice alone, to publish The Bell Jar. Her mistakes were to ignore her own human fallibility and to believe she could control the future, and, especially, to allow her shadow self, the cold, heartless, mirror double which she saw so clearly in her poem, ‘Mirror’ (SPCP 173-4), to dominate the warm, loving, natural energies which were also within her. In effect, Sylvia had become the Gemini twins of the Lovers’ Path. Her love was turned inwards and was self-focussed, and even within herself that love was divided and unbalanced. Inevitably, in Cabbala and in life, such lack of wholeness and harmony is costly.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

1. The importance of the ‘Shabbat Queen’ and the symbolic meaning of the shape of the letter ‘Zain’ is discussed in Zain - The Mystical Significance of Hebrew Letters (ZAIN).

2. There is little agreement about the paternity of either Castor or Polydeuces. Some say Zeus fathered both: some that King Tyndareus did. Some say Castor was fathered by Zeus, and Polydeuces by King Tyndareus. Leda, their mother (with whom Zeus mated in the form of a swan) was, however, the daughter of the gods, Zeus and Nemesis. The whole story can be found in Graves, R. Greek Myths, Cassell, 1981. pp. 71-3.

3. Alternatively, Eros was fathered by Zeus; or he was the son of Aries (Wind) and Nuit (Night), hatched from a silver egg and hidden in a cave by Nuit who stood guard as a Triple Goddess (Night, Order, Justice) whilst at the entrance to the cave sat Rhea, playing her drum.

4. Graves, R. The White Goddess, Faber, 1977. pp. 256-7. Campbell, J. The Masks of God: Occidental Mythology, Penguin, 1980. pp. 158-161.

5. Hughes, T. Book review of The God Beneath the Sea by Garfield and Blishen, Children’s Literature in Education, No.3, 1970. pp. 66-7.

6. This hairband was clearly something Sylvia valued and would not have parted with lightly. In her journal entry she calls it “my lovely red hairband” and “the red bandeau which I loved with all the redness of my heart”. In Sylvia’s semi-fictional account of the St Botolph’s party, ‘Stone Boy With Dolphin’ (JPBD 297-32), the heroine’s stolen hairband is also red.

7. Myers, L. Crow Steered Bergs Appeared, Proctor hall Press, Tennessee, 2001. p. 32.

8. Spencer. N. True as the Stars Above, Victor Gallacz, London, 2000. p. 230.

9. The suggestion here is of the lightning flash from the Divine Source illuminating the essence of Sylvia so that Ted sees her, as he writes the poem, stripped of the shadows formed in his memory by later events.

10. The phrase appears, for example, in two letters. One addressed to Antonio Canigiani: ‘De musica: On music’ (No. 92); and one to “Alessandro Braccesi, a priest of the Muses”, ‘Vera poesis a Deo ad Deum: True poetry is from God and for God’ (No. 131). The Letters of Marsilio Ficino: translated by members of the Language Department of the London School of Economic Science, Shepherd-Walwyn, London, 1978.

11. ibid. Letter 7, ‘De divino furore. On divine frenzy’.

12. Neil Spencer disagrees with my comments about astrological jargon. As an astrologer he finds that part of the poem “crucial information and very eloquent”. For him, it demonstrates that “the evening was heavy with portents” and it explains exactly how Ted and Sylvia were married by the solar system. In a letter to me (12/12/2001) he wrote: “[Ted’s] and Sylvia’s charts were both struck strongly by that night’s transits – hence they were ‘married’. Principal transit mentioned for this is “the day’s Sun in The Fish” (Pisces) which fell on Sylvia’s ascendant and opposite Ted’s Neptune (Ascendant equals self, Neptune is idealism / glamour / love-struck – also opposite the ascendant (first House of Self) is the seventh House of Marriage!). Ted mentions some other overlaps. Their charts were heavily entwined, so that on March 25th the planets hit them both”. Neil writes, too, that the Jupiter / Moon conjunction spelt “disastrous expense” especially for Ted, “because it ‘combust’ his Sun. ‘Combust’ is a mediaeval term referring to the Sun being too close to another planet and thus scorching it. He’s taking poetic licence – Jup / Moon can’t combust his Sun because they don’t have fire. But he’s got the point. He was blown up by the night’s major aspect. Interestingly he does not mention Pluto that’s also present between the Moon and Jupiter, now that really will blow you up – but then Ted really was a Renaissance astrologer”.

13. Sylvia’s journal entries for July and August 1957 show her struggling with bad dreams and mood swings. She was trying out ideas for stories and poems but despairing of writing them, and she was terrified that she might be pregnant.

14. Sylvia began teaching at Smith College in September 1957. Ted began teaching at the Amhurst campus of the University of Massachusetts at the end of January 1958.

15.“… the Great Goddess… can be seen as the creative womb of the inchoate waters, gradually refining into human form, and everywhere tending to be fish-tailed”. (SGCB 6).

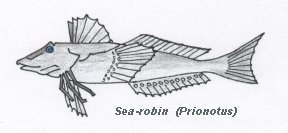

16. The Northern Sea-robin of the Cape Cod area is a small, bottom-dwelling fish with spiny fins, a bony head and notably blue eyes. It is not bad eating but is generally regarded as scrap and used in pet-food. The name, linking ‘sea’ and ‘robin’ is beautifully apt for Ted’s purposes in this poem, because it marries the Goddess to the God, whose bird in Northern folk-lore is the robin redbreast.

17. Ted’s first book of poetry, Hawk In The Rain, was published in England and in America in September 1957.

18. Throughout Birthday Letters, America symbolizes a land of promise, the New World and a mythical El Dorado.

19. The Economic Research and Development Group website (www.horseshoecrab.org/) provides a wealth of information about the Horseshoe Crab.

20. Robert Graves makes this identification in The White Goddess in the course of his discussion of the Triple Goddess and her golden apples. (TWG 255).

21. The requirement made of those accepting this award was that they live for at least three months outside Great Britain and Ireland. After months of excited planning and preparation for a trip to Italy, Sylvia finally wrote to tell her mother that Ted had given up the award and she was relieved that “the strain of going to Italy” was not “on top of us any more” (SPLH 25 August 1961).

22. The Devonian dialect can be impenetrable to strangers and there are still traces in it of the old Celtic language of the first Britons.

23. In ‘Lady Lazarus’ (SPCP 244-7), she claims of her projected suicide: “This is Number Three”.

24. Considering Sylvia’s identification of Otto with The Colossus and with Thor, it is interesting to note that The Statue of Liberty, the female icon which symbolizes America, is (in the poem inscribed on its base) “The New Colossus / Not like the brazen giant of Greek fame” but “a mighty woman with a torch / whose flame is imprisoned lightning”; she is “Mother of Exiles” who stands at “the golden door”. (Emma Lazarus. 1883).

25. Ted’s note in SPCP (p. 292) suggests that the contract was signed in 1962, Anne Stevenson gives the earlier date in Bitter Fame (p. 226) and the reason for its postponement. Sylvia refers to this in a letter to her mother on 20 November 1961 (SPLH).

26. Anne Stevenson suggests that this name “was drawn from Ted’s world”, ‘Victoria’ from Vicky, his cousin, and ‘Lucas’ from Lucas Myers (BF 227). However, considering the discord between Sylvia and Ted at that time, and Sylvia’s fierce independence, that explanation seems unlikely.

27. ‘The Signature’, Stonepicker, Bloodaxe Books, 2001 ( p. 75). Interview with Libby Purves, The Times ( Features), December 1999.

Poetry and Magic text and illustrations. © Ann Skea 2002. For permission to quote any part of this document contact Dr Ann Skea at ann@skea.com