|

‘Moon-Dust’(H &W 9, THCP 1180).

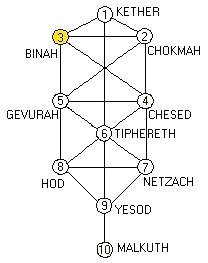

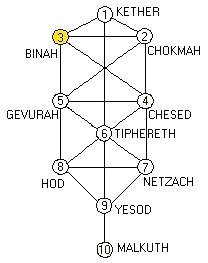

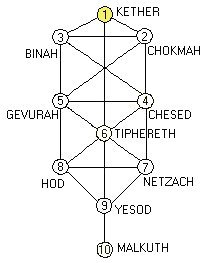

Binah: Sephira 3: Understanding. Truth.

Intuition.

|

Above Daath on the Averse Tree lies Shahul, which is known as ‘The Triple Hell’ or ‘The Grave Hell of The Supernals’. This First Palace of the Averse Tree contains the combined Qlippothic energies of Kether (1), Chokmah (2) and Binah (3), the demons of which are, respectively, Thamiel (The Dual Contending Forces); Chaigidel (The Hinderers); and Satariel (The Concealers).

Always Binah and Chokmah work together to channel the energies of Kether to the lower part of the Tree. Binah, the All Mother and Chokmah, the All Father, must be united before new life can be created in the world of Nature. She is the egg and the womb: he the fertilising sperm. She gives Form and shape to his undirected Force. But in the Qlippothic Sphere of the Triple Hell, her Judgment may be especially merciless and completely stultify or imprison his energies: and his Mercy may be actively misdirected and unjust and, so, cause chaos and destruction. All three of the Supernal Sephira are connected by Daath to the Abyss, and, whether their energies are Qlippothic or not, they have particular creative and destructive power.

In the proof copies and in the published editions of Howls & Whispers, ‘Moon-Dust’ is poem 9 and ‘The Offers’ is poem 10. Together they occupy the Sephiroth of Binah and Chokmah. In the early draft list of poems which is amongst the Baskin – Hughes papers at the British Library, the order of these two poems is reversed. However, both poems have male and female aspects, and in both poems the energies are clearly out of balance due to Sylvia’s death. And, since the energies of Binah and Chokmah work together at this level of the Tree, either of these poems could sit at either Sephira without upsetting the overall balance of their conjunction.

Curiously, on one of the sketches which Baskin made for the etching which would accompany ‘Moon-Dust’, he has written the title as “Moon lust” 1. It is impossible to tell whether this is deliberate or a mistake2, but ‘Moon lust’ nicely glosses the first stanza of Ted’s poem, in which Sylvia’s “passions” are his subject. Passion, however, is not always synonymous with lust. Not does it necessarily entail sexual desire, although this would appropriately reflect the sexual fertilising nature of the union of Binah and Chokmah.

Sylvia did, indeed, have many passions. In fact, almost everything she did was done with passion. She was vehement in her pursuit of the aims and objects on which she focussed, driven by overpowering, often irrational zeal, and subject to outbursts of feeling and emotion. There was passion, too, in the pain and suffering she willingly endured in order to achieve her goals.

Sylvia’s passion launched her quest for wholeness. And in ‘Moon-Dust’, Ted’s image of Sylvia’s face left “like the dandelion” (which is a symbol of passion in religious art and also a golden, sun-reflecting flower of the Goddess) “at the edge of the launching pad”, suggests how small and vulnerable, yet persistent and tough, she was in the face of such a huge endeavour.

Sylvia’s “story”, too, (not her life but the imaginative story she made of it in all her writing and her art) was fuelled by her passion. But that passion had “been and gone” by the time Ted wrote this poem, and what he saw when he looked back was only a rocky fragment, a “cratered moon”: a real but mysterious place of myth and imagination and great ventures, in which his own story seemed to exist like that of a visiting astronaut.

Ted chose his imagery carefully, here, for the “capsule on its tripod” and the “few rocks” which he collected on this moon-visit both suggest the concealed potential which is part of Binah’s power. In her womb, as in the cauldron of many a Moon Goddess or Mother Goddess3, new life gestates: and her “peculiar rocks” (like those brought back to Earth from the Moon) are pregnant with hidden potential. Literally and poetically, just a single flower, like the harebell in Ted’s early poem ‘Still Life’ (W 18, THCP 147 – 8) or the even earlier “Snowdrop” (L 58, THCP 86), has the power to break open these rocks and release that potential.

In the first twelve lines of ‘Moon-Dust’, Teed recalled the rocky, uncertain landscape of the past. “Now”, in the final stanza, he borrows the powers of that flower to reveal its hidden life. “Now”, standing firmly in the present, in a single line which has the force of a command, Ted poetically and magically directs Sylvia (with “only her cheek lit”, like a setting moon) to “Sink in the West”. So, Sylvia enters the realm of Binah as Ama, the Dark Sterile Mother. But the Illusion of Binah is Death, and in the West lies, also, the mythical Land of Promise, the realm of Binah, Mother of All Things, the place of new beginnings.

Given Binah’s double aspected nature, it is appropriate that Sylvia enters the darkness with the last of the sun reflected from just one moony cheek4. But since passion was the launching pad of Sylvia’s creative “story”, and passion also fuelled “giant, weightless leaps” in Ted’s imagination, it is certain that Ted’s reference to Sylvia’s “cheek” was an intentional pun. ‘Cheek’ may refer to a part of the face but it also means ‘effrontery’, ‘cool confidence’ and the sort of courage and impudence which are the valuable components of passion and are powerful motivating forces in any difficult venture.

That same ‘cheek’, is also linked to Ted’s own difficult poetic venture by his final image of himself studying “these peculiar rocks” which are literally and metaphorically the words of his poem. He imagines himself “touching at them”, “like a flower” nodding in a breath of animating wind, in his own attempt to reveal whatever life lies concealed within them.

This is the potential which even the most fragile of the Goddess’s flowers has the power to reveal. And this is the light which lies concealed by the demons of Binah in the Qlippothic darkness of the Averse Tree.

Moon-dust, for poets, is a magical substance, the source of mystery, inspiration and madness. If we borrow Baskin’s apparent title for this poem, we might say that passion, if it is uncontrolled and has the naked Force of Chokmah, can easily result in the madness of Moon lust. Binah, with her great powers, can fix and contain that Force. Or, by combining her Understanding with Chokmah’s Wisdom and using more balanced control, she can transform it into the imaginative stimulus of Moon-Dust.

|

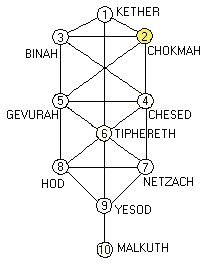

‘The Offers’(H &W 10, THCP 1180).

Chokmah: Sephira 2: Wisdom. Creativity.

|

Perhaps because Chokmah is the source of the male creative energies, and the place of the Magus, Magician and poet who each seek the help of the Goddess to channel those energies into our world, the story told in ‘The Offers’ (H & W 10) is, more than in any other poem in Howls & Whispers, not what it seems. Like ‘Moon-Dust’, it shares the energies of Chokmah and Binah. It deals with the effects of female on male. And it describes the way in which a powerful, concealed, female spirit intermittently surfaces to arrest, disturb, and seek to control and direct the male energies. As always in Howls & Whispers and Birthday Letters, it presents a realistic, seemingly factual story, which many will accept as a true, if puzzling, account of events. But below that surface story lies a mythic, Cabbalistic level which is wholly involved with Ted’s own creativity and his fundamental belief in the purpose and the power of poetry.

Based on his own experience, Ted presumed that all poets “draw on a mythic substructure of some kind” (SGCB 39). And, as he noted in Shakespeare and the Goddess of Complete Being, “wherever [Shakespeare’s] dramatic characters have a mythic personality they tend to have other busy lives in other mythic realms” (SGCB 35)5. And, at the deepest level of ‘The Offers’, in which Sylvia represents the Goddess and Ted, her consort6, Ted drew on myths which were probably amongst the earliest he ever encountered and lay deepest in his memory.

In 19647, Ted wrote of the deities of these Northern mythologies as “an essential part of our instinct and imagination”, and as being “much deeper in us, and truer to us, than the Greek-Roman pantheons”. “One has only to look at our vocabulary”, he continued, “ to see where our mental life has its roots, where the paths to and from our genuine imaginations run, clearly enough.” (WP 41 – 2). So, it is not surprising that these Northern deities should have surfaced in his imagination when he was dealing with Chokmah’s creative powers, and the control which Binah has over them.

One of the most puzzling images in ‘The Offers’ - that of Ted “kicking free” from “the bottom of the Rhine” – suggests that the mythic parallel which Ted had in mind as he wrote this poem was that of Siegfried and his encounter with the nixies or water-sprites, who are the Rhinemaidens in Wagner’s telling of this tale in his Ring cycle.

The underlying quest pattern of the Northern myths of which Siegfried is the hero, is essentially the same as that of the Cabbalistic quest8, but the connections of both with ‘The Offers’ are veiled. Ted’s mention of the Rhine, however, at the central point of his poem, comes at a time when he was separated from his first true love, just as Siegfried was when the Rhinemaidens beguiled him from the depths of their river. Ted, too, was now “courted…covertly” by a woman who seemed wholly real: yet she was also Sylvia / “you” / the Goddess, and she “moved easily” in the “underworld”, and had “other spirits” who “colluded” with her “in a support team”. In her eyes Ted saw a “Ferocity of longing” for something which (like the stolen Rhinegold) had been “repossessed”. But rejecting her “gentle ultimatum”, Ted, like Siegfried, “kicked free” of these female energies which enticed and “bewildered” him.

Once again, as in ‘The City’, this word ‘bewildered’ is important, and suggests that Ted was on the edge an Abyss which, in the context of Chokmah, would be a desert devoid of creative energies. So, the offer he was being made was not as seemingly simple as the story-level of the poem suggests. At a deeper level, he was being offered a choice between succumbing to “the inertia of life’s momentum” and giving up the difficult path of his poetic quest; or of recognising that to do this would simply be to repeat old patterns, “same masks, same parts, / No matter who the actors”. Just as Siegfried’s encounter with the nixies was a test of his courage and of the strength and purity of his love, so Ted’s second encounter with Sylvia’s spirit was a test of his ability to discriminate between illusion and Truth; a test of his strength of will; and a test of the selflessness of the love which had, up to that time, guided him on his quest.

The traditional mythical and magical initiation of any hero requires that three such ordeals must be faced, and, as Ted truly believed and stated in ‘The Offers’, “Everything is offered three times”. In a Cabbalistic context ‘everything’ encompasses the whole, the Unity, which is the goal of the Cabbalistic quest. And in ‘The Offers’, Sylvia’s spirit does challenge Ted three times and three is the number of the Goddess, Binah.

With this in mind, the three manifestations of Sylvia’s spirit in ‘The Offers’ resemble, respectively, the “yellowish”, “morgue”-touched Goddess of Death-in-Life and Life-in-Death; the mature, experienced, motherly Goddess; and the Virgin Goddess who is “half wild roe”, “flawless, priceless”, and whose colour is the “cobalt” blue of the pure Spirit.

An offer always suggests a choice, and Ted’s first encounter with Sylvia’s spirit in ‘The Offers’ also had elements of testing and choice about it. This encounter took place two months after Sylvia’s death, so the month was April, which is the natural and mythological time for rebirth in the Northern hemisphere. Realistically, Ted’s experience was just like the sudden glimpse of a dead loved one which is not uncommon amongst the newly bereaved. But although rationally Ted knew that the woman he saw was not Sylvia – that this was “plainly impossible” – the uncanny conviction that Sylvia was present, that this dream “was no dream”, and that some offer was being made to him, caused him to respond as if to a test. In fact, he described this revelation of Sylvia’s spirit as being (and his line is wonderfully ambiguous) “For my examination and approval”.

But what was being examined? His ability to discriminate between dream and reality? The strength of his spirit’s will over hers as he tried to “manifest” himself and force her physically to notice him? His “daring” – the courage to speak to her or to “make some effort to seize / This offer”? Convinced as he was that Sylvia was there, but wearing “a new face”, he still hesitated, bargained with “death” who seemed to have made this revelation, and set his own “testing moment”.

Clearly, Ted was not wholly taken in and, however real this experience felt, he was still able to discriminate between Sylvia’s “face” and “the new face” that this “saddened substitute” wore. But his sense of loss was no less acute as he was left alone again with the “original emptiness” he had experienced that first time when Sylvia had “been” in his world and then “abruptly” was not.

There are veiled suggestions of Norse myth, too, about this first offer. Realistically, since the Northern Line on London’s Underground network does run North, Sylvia’s seeming reincarnation disappeared “Northwards”. But the North is also the frozen, sunless realm of the Norse Goddess, Frigga, from whose cauldron poets and heroes are reborn. And Frigga’s cauldron appears again in the final poem of Ted’s journey on the Averse Tree.

The second “offer” and the Goddess’s second testing of her chosen one was as disturbing, disorientating and hallucinatory as the first, and just as real. Again, Ted experienced the “doubled alive and dead existence”, “the dream…that was no dream”.

Ted’s response to the first offer had been emotional, and his bargaining for time purely instinctive. The lack of response of that first woman, plus the finality of her disappearance, had been harsh and painful to him. With the second offer, his response was more rational, and experience and “thought” made him question the situation, so, “gasping for air” but still with difficulty and uncertainty, “indolently like somebody drowning”, he had “kicked free”. This second time, the woman responded with more understanding, as if Sylvia (who is always also the Goddess) had gently and with “ghostly humour” allowed him to remain, like “a hostage” in the “land of the dead”: until, presumably, some payment had been made which would set him free.

The land of the dead, is both the illusory, dream world of Maya which Ted described as “the whole of London’s waking life”, and the darkness of Ted’s own spirit after Sylvia’s death. Together, as Ted has suggested throughout Birthday Letters and Howls & Whispers, he and Sylvia had sought, through their creations, to heal themselves and their world. Sylvia’s death ended this shared endeavour. But it did not end Ted’s own quest. Following his rejection of this second ‘offer’, in lines which are clearly metaphorical, since at no time was Court Green “in ruins”, Ted described their shared poetic journey as “our house”. And he described how, after Sylvia’s death, “even in dreams” all that they had built together seemed to fall apart and his own painful poetic attempts to continue the journey alone seemed doomed to failure. He needed, first, to heal himself by understanding all that had happened, but for many years he was unable to deal directly with this task.

In one of his last letters to Keith Sagar (18 June 1998)9, Ted discussed this failure to deal with “that part of my life” until Birthday Letters, and he provided a broad outline of his earlier attempts. Shortly after Sylvia’s death he wrote ‘The Howling of Wolves’ and ‘Song of a Rat’, then nothing “but rubbishy efforts, radio plays, prose” until he “found a way out of a three year impasse with ‘Skylarks’”. After that the Crow poems began to arrive, until the deaths of Assia and Shura revived memories of Sylvia’s death and his mother’s death and caused “a big psychological meltdown with accidental complicating factors which knocked Crow off his perch.”.

Ambiguously, Ted described his work with Peter Brook shortly after this as an “escape”. Whether he meant that it was an escape from his own darkness is not clear, but it did entail, he said, “total suspension of my own writing except for that little myth of sinister import and total inner stasis, Prometheus on his Crag…”. The imaginative stimulus of working with Brook however, did lead to Cave Birds which, in a much earlier letter10, Ted described as having put him “through a process in a therapeutic way”. Then came Remains of Elmet and River, in both of which he immersed himself in the Mother Goddess’s world of Nature in order to confront death, deal with discordant energies and, so, achieve some kind of rebirth11.

All of this suggests that The Goddess did demand attention from Ted at various times in his life and that by allowing her to guide and focus his creative energies in his poetry he did find therapeutic relief.

Perhaps, then, Remains of Elmet and River coincided with Ted’s second encounter with Sylvia’s spirit, as described in ‘The Offers’. Certainly, both sequences deal closely with the Mother Goddess and the cyclical manifestation of her powers here on Earth. Remains of Elmet begins with Ted’s evocation of the spirit of his own mother in a poem which, in the later publication, Elmet, is entitled ‘The Dark River’. And it is ‘The Mothers’ and all their energies (literal, metaphorical, alchemical, mythic etc.) which prevail in both sequences12.

In Remains of Elmet, the energies of Binah predominate: in River, those of Chokmah, which are often symbolized by a river, are most apparent. Nevertheless, in the poetry of both sequences Ted immersed himself and his readers in the Goddess’s world, waded into his own subconscious, participated imaginatively in birth and death, and, finally, glimpsed “the nameless”13 which unifies all.

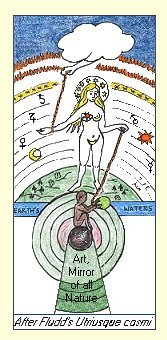

The Goddess with whom Ted negotiated in Remains of Elmet and River, like the Goddess embodied in the second woman in ‘The Offers’, was the Goddess of our world. She was Nature, who connects all the creative energies of our world to the Divine Source through the Golden Chain of being, as in Robert Fludd’s illustration14. Ted’s glimpse of the nameless came through his connection with her, but awe-inspiring as it was, it was fleeting, and he quickly returned to the world of Nature, ending River with words in which his vision is beautifully condensed, like dew on “old haws”.

Some time in 1980, Ted wrote to Keith Sagar that River was “finished more or less”. And in 1981 he wrote that he was “involved in the coils of the Plath journals” and that his own “compositions” had “been in hibernation…for pretty well a year” (TLOF xxviii15). About this time, too, he described his own writing as “some sort of fight for life”, a fight which was so “important” that as soon as he came “to the second wind and fresh shot of revision” it drew him back in until he was “gasping for air”16. For whatever reason, after River, Ted kicked free of his immersion in poetic negotiations with the Goddess and wrote, as he told Sagar, “for 5 or 6 years nothing but prose – nothing but burning the foxes”17.

By 1991, Shakespeare and the Goddess of Complete Being was published and Ted told Baskin that he had emerged from the “Shakespeare tar-pit” wondering “what verse” he would be able “to produce now, after all that”18. Translation got him “off [his] own rails” for a while, he told Keith Sagar, but this was “all done by 1994”. At this point, it seems, Sylvia / the Goddess again demanded his attention and he began, as he told me in 1995, to write about things he “should have resolved thirty years ago. Should have written then, but couldn’t”.

For the first time, then, he dealt directly with those things, and in 1995 he told me that he had written “about 100 poems”, a few of which he allowed to be published in his New Selected Poems. Was this the “testing foot” which he lowered “into the running bath” in ‘The Offers’? Was this when he heard the familiar voice “urgently” demanding “Don’t fail me”? “Finally”, he wrote to Keith Sagar, “I cracked. I got together all the Birthday Letters, wrote some more – with mighty relief, and…published them”19.

All the feelings which Ted went on to express about those Birthday Letters poems in his letter to Sagar – that they were “so raw, so vulnerable, so un-processed, so naïve, so self-exposing and unguarded” – all are summed up in that image of his “helpless moment” in ‘The Offers’. Yet the moment when Ted first stripped away all masks and prepared to immerse himself, naked, in episodes from his and Sylvia’s past; to re-create them as fully as possible in his imagination; and to record them in his poems, was equally his “helpless moment”. And the last time Sylvia’s spirit revealed itself to him in ‘The Offers’, she not only appeared as the Virgin Goddess, the Goddess of Love to whom all Cabbalistic poetry is dedicated, she also came in a manner which has many mythological precedents.

The bath, always, in mythology and religion is a place of ritual purification or baptism. It is a threshold where, symbolically, worldly things are washed away so that the spiritual life may begin. It is a place of transformation and rebirth, and a place where one is naked and most helpless. Many mythic kings and heroes were killed in their baths 20. So, this third and “last time” that Ted heard the familiar voice out of the temporal “river’s uproar”, it came with warning associations which he was well equipped to recognize, just as he recognized its “peremptory” and “urgent” command.

At this point in Ted’s life, and in his Cabbalistic journey, he was prepared for the self-purification, purging and intensification of purpose which is required at the Cabbalists’ ‘Third Gate’, through which he needed to pass in order to reach the inner Temple and find the Truth and wholeness that he sought.

In the Cabbalistic journey which Ted undertook in Birthday Letters and Howls & Whispers, he tried his utmost not to fail either Sylvia or the Goddess. And, as ‘The Offers’ suggests, in his necessary dealings with the Averse energies in Howls & Whispers, whilst the demons of Chokmah (the Chaigidel or Hinderers ) tempted him with spurious offers designed to deceive and distract him from his quest, ultimately they served only to test his readiness for the task. This, then, was the light which Ted salvaged in ‘The Offers’ from the Qlippothic darkness of Chokmah.

|

‘Superstitions’(H &W 11, THCP 1183).

Kether: Sephira 1: Crown. Fire

|

‘Superstitions’ (H & W 11) is the final poem in Howls & Whispers and it lies as Sephira 1, Kether, at the crown of the Averse Tree.

In Ted’s typescript list of poems21 and in the proof copies of Howls & Whispers, ‘Superstitions’ is numbered as poem 11. Eleven is the number of the ‘Accursed Shells’ of the Averse Tree 22 and it is a most powerful prime number, a Cabbalist’s ‘master’ number and the great “general number of magic, or energy tending to change”23. It combines antitheses, “embraces the opposites in both heaven and hell” (SSN 97) 24; and its energies can be used by the Adept to “bind all opposites together, each to its complement” (SSN 96) in order to bring everything to equilibrium. All of which is appropriate for the final poem of Ted’s Cabbalistic journey.

Eleven also amplifies all the powers of 1: and 1 is the Monad, the All in “latency or suspension” (SSN 1) from which all of the manifest world proceeds. Everything begins at 1, as it did in Birthday Letters and ends at 1, as it now does in Howls & Whispers. And if Ted had successfully dealt with all the energies, positive and averse, and had passed the necessary tests set by the Goddess, then this final poem should have allowed him to complete his quest, to unite Wisdom and Understanding in the light of the Divine Source, and to bring his ‘Great Work’ to completion.

The position of ‘Superstitions’, therefore, as poem 11, at Sephira 1 (Kether) at the Crown of the Averse Tree, and as the poem which completes Ted’s poetic Cabbalistic journey round that Tree, is one of supreme importance. Why then, if 11 is so powerful and its amplification of 1 so great, did Ted invoke the powers of 13 in this poem?

Certainly, “Friday the thirteenth” is widely perceived as a combination of day and date which is full of portent. Yet, neither this, nor superstitions in general, nor the fragmentary references to myth, religion and history in the poem, seem to have much to do with the story Ted has told so far in Howls & Whispers.

This story, as in Birthday Letters, tells of Ted’s and Sylvia’s meeting and marriage, and of Sylvia’s death and its consequences. But, clearly, ‘Superstitions’ was important to Ted in contexts other than that of his life with Sylvia, for he also used it as the first poem in Capriccio25, the limited edition of twenty poems about Assia Wevill. What, then, might Friday the thirteenth mean which makes it relevant to both sequences?

Thirteen, as any dictionary of symbols will confirm, is a numinous number, one which indicates the presence of a god, and it is both lucky and unlucky. It is the number associated with the Sacred Kings and sacrificed gods; with the end of corrupt worlds and the creation of new; with the Hanged Man of the Tarot; and with Mem, which is the thirteenth letter of the Hebrew alphabet and represents the Sacred Feminine.

In Cabbala, 13 (represented as numerals, rather than by letters) unites the undifferentiated energies of 1 (Kether) with the form-giving energies of 3 (Binah). And in Cabbalistic magic 13, like 11, is uniquely powerful, for in Cabbalistic lore “Through the proper assemblage of the forces of 12 and 1, or 13, ‘All the forces of heaven and earth are given unto you’”. (SSN 105). And 13 also represents “either death through failure and degradation, or the attainment in regeneration of a New Order of the Ages. There are no halfway measures with 13, it demands all or nothing” (SSN 106).

The relevance of this last quotation to the regenerative quest of the Cabbalist, and the way in which the patterns it describes are demonstrated in the particular stories of myth, religion and history to which Ted refers in ‘Superstitions’, is readily apparent to those who know those stories26. Each of the god-heroes Ted chose – Balder, Christ and Columbus – came from a corrupt world to offer a vision of a new, golden, uncorrupted place – a ‘New Order of Ages’. But each was destroyed by the dark energies of the world around them. And it is this inseparable combination of contrary energies in our world (light-darkness, Sun-Moon, Male-Female, good-evil) that 13 also represents.

Crowley, using a Cabbalistic method based on the numerical value of Hebrew letters, drew on the Sefer Yetzirah27 to demonstrate that 13 is “ACHD, Unity” and “AHBH, Love” (‘Gematria’, 777, p. 29), and also “Hated, AIB” and “Emptiness, BHV” (‘Sepher Sephiroth’, 777, p. 2). And the double aspect of 13, which is reflected in these words, is also present in the powerful Qlippothic demons, the Thaumiel (‘The Two Contending Forces’, ‘The Twin Gods’) which occupy the apex of the Averse Tree and are described as ‘The Bicephalous Ones’.

Baskin’s accompanying etching for ‘Superstitions’ in Howls & Whispers, captures exactly the united but double nature of 13 in an image of a single head on which two faces appear in profile.

“Friday”, too, has its own magical significance, for Friday is Freyja’s day, the day of the most powerful of the Norse Goddesses, who is yet another form of Binah. Ted, by threefold repetition of her name in the first two lines of ‘Superstition’, invoked the Goddess’s presence in his poem and, thus, in our world; and he invoked her “Today”, which is the continuous and immediate present.

It is apparent that “Friday” and “thirteen” together combine all the associated powers of each. And this power must be magnified at the Apex of the Tree, where the Supernal Triangle of Sephirothic energies prevail. Friday the thirteenth, therefore, is a date to stand in awe of – which was the original meaning of ‘superstition’28.

Ted’s poem is full of gods and heroes of whom we have stood in awe, and with whom we have associated Friday the thirteenth in myth, folk-lore and fable. And it warns of the terrible, blind foolishness of ignoring or laughing at our superstitions.

Figuratively, and Cabbalistically (in its line numbers), ‘Superstitions’ charts our descent into increasingly worldly and inflexible representations of the human search for Truth. It moves from the creation, death and burial of our earliest, primordial ancestor (lines 1, 2); to our earliest, imaginative explanations of the world (lines 3, 4, 5); next, to the fixing of our ideas about occult power in the dogma of religion (lines 6, 7)29; and, finally (lines 8, 9, 10, 11), at the lowest, most worldly level of the Tree and completing the Qlippothic pattern, to our creation of human heroes, who, like Christopher Columbus, physically and rationally discover ‘Truth’ for us by exploring the world geographically or scientifically.

Similarly, ‘Superstitions’ charts the progressive lowering of our spiritual horizons, as our vision of the redemption and healing of our corrupt world, and the achievement of a new and more harmonious life, becomes increasingly unimaginative, codified, inflexible and Earth-bound.

Ted’s poem, however, does not end at line 11 but continues on for another 17 lines in which the unpredictable, “two-faced” energies of 8 (17 = 1 + 7 = 8) prevail.

Eight is not just the number of Mercury as the eighth planet, and of Hermes-Mercury who is the spirit which moves between our world and the world of the gods, it is also the number of “the feminine in exultation”, the “Double feminine” (SSN 66). And the Goddess is double aspected, “two-faced” in many ways. She is the gatekeeper who controls the supernal energies which flow into our world; her Judgment, too, like that of Frigga in Valhalla, determines who from amongst us will be allowed to access the immortal energies of the Source. From Frigga’s cauldron, dead heroes were reborn to live with the gods in Valhalla: so, too, may the Cabbalistic hero be chosen by the Goddess to receive the “gift” of spiritual rebirth. In 13, she stands beside Kether, united by Love. But to Cabbalists, 13, is also 10 plus 3, and Binah is then known as ‘The Bride of Malkuth’ (10, the World) and their union is like the “root with the fruit” (MQ 141): then, she is Nature, the Mother of all Living, and the Moon Goddess. Her number, 3, represents the lit, visible side of her moon-face. Joined to its mirror image, 3 becomes 8, the Mercurial Spirit and the Double Feminine.

In two groups of three lines (12 – 14 and 15 – 17), Ted first brought Freyja into the world with “Friday the thirteenth” and connected her energies by a highly ambiguous “you” to Sylvia, himself and us; then, he joined Frigga (the same Goddess but in her role as guardian of birth, death and transfiguration) to her cauldron in Valhalla “where human warriors were reborn”. Essentially, these six lines show the Goddess in her two roles; as 13, the supernal “Prestidigitateur” who controls the flow of Supernal energies into our world; and as 3 married to 10, ‘The Bride of Malkuth’ who sits “on the Throne of Binah” (MQ 141) and controls our human access to the Source. Also, in these six lines Ted performs the function of the Mercurial Magus by bringing the spiritual and material worlds together.

This is the most he can do. The Goddess, whose energies are those of Judgment, “may” or may not “find odds and ends” for us, for him or for Sylvia; and “maybe”, like Frigga, she will choose us for rebirth. In her cold, lit, moon-face, only a single eye (which, symbolically, is always the Divine “I” which denotes all godly powers) is visible. But hidden in its shadowed corner, under the epicanthic fold30, we may glimpse her magical cauldron.

In the version of this poem which begins the Capriccio sequence, Ted instructs us to “imagine the bride’s mirror”; to imagine, in other words, the hidden, mirror side of the Moon-Goddess’s face. Imagine it, he directs, “In the form of a cauldron. Call it a cauldron / of the soul’s rebirth”.

In both poems, the seven lines which immediately follow are identical.

What we will see, if we use our imagination to look beyond the physical veil, is not an arbitrary process but one in which the fate of each individual – “this one”, “that one’, “this other one” – is determined. Like Frigga, the Goddess judges us. “This one” (who has passed the tests which questing heroes must pass) may find eternal life; “that one” may be reborn on Earth as so still subject to death; “this other” remains in the chaos of swirling, undifferentiated, unformed energies in the cauldron – unborn and, so, “without a cry”.

“You will be laughed at / For your superstition”, Ted wrote in the Capriccio version of this poem, choosing the spacing and line breaks so as to emphasize this warning. But in Howls & Whispers he is uncharacteristically forceful and directive: “Let them laugh / At your superstition”. Again these two lines are given particular emphasis by his spacing and line breaks; and they also stand free of the lines which follow thus giving them even greater importance.

In both versions of the poem, the final two lines are identical; and in both poems they are enclosed in parentheses, so that they appear as if they are an afterthought, an almost casual comment separated from the rest of the poem. Their content, however, is far from casual. And the images Ted draws in them are of happenings which are un-natural, inexplicable and terrifying – exactly the sort of thing which would provoke the fear and awe which define superstition.

Appropriate as this may be, there is far more to these final lines than is immediately apparent, and the key word in them is “Remembering”.

Remembering, for Cabbalists and NeoPlatonic Hermeticists is exactly that: re-membering – putting back together the scattered and separated parts of a body in order to make it whole again. Memory and imagination, they believe, link us directly to the Divine31. Remembering requires us to use our will, our courage and our determination to find and gather those separated parts, then to use our imagination to re-create and re-vivify the whole.

Remembering is what Ted has tried to make us do throughout this poem, by providing fragments of stories in symbols and names, and by creating suggestive patterns to remind us of our origins and of our various ways of interpreting the world and seeking Truth.

Remembering is what Ted did throughout Birthday Letters; what he did as he searched for light amongst the Qlippothic fragments in Howls & Whispers; and what he did also in the Capriccio sequence, which begins with ‘Superstitions’ and ends with him finding the keys of the sycamore, which is the Goddess’s Tree of Life.

Remembering requires our awareness that whilst the Whole unites all contraries, in our fallen world - the world controlled by Nature - the energies become increasingly divided and polarized. We must remember and accept that the contraries - life and death, light and darkness, laughter and sorrow – are each part of a spectrum in which both are always present. As the thirteenth century scholar, Boncompagno, stated most emphatically “WE MUST ASSIDUOUSLY REMEMBER THE INVISIBLE JOYS OF PARADISE AND THE ETERNAL TORMENT OF HELL”[sic.]32.

In ‘Superstitions’ Ted makes the same warning. And he goes further. He tells us that remembering is not easy: that it will make you sweat, burn and bleed. If you seek wholeness, you must know and accept this, even if others laugh at your superstition. For, as Blake so beautifully put it in his “Pickering” manuscript:

Man was made for Joy & Woe,

And when this we rightly know,

Thro’ the World we safely go.

Joy & Woe are woven fine,

A Clothing for the Soul divine;

Under every grief & pine

Runs a joy with silken twine.

So, finally, in ‘Superstitions’ Ted brought together all the fragments of light he could find amongst the Qlippothic shells of the Averse Tree and, in the presence of the Goddess and with her help, he completed this remembering: for Sylvia, for himself and for us.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

1. This sketch (dated “26.F.98”), together with other preparatory sketches for this poem and for the rest of the poems in Howls & Whispers, is amongst the Baskin-Hughes papers in the British Library.

2. On a second sketch for this poem the title is ‘Moon list’. Baskin’s writing is clear and the way he forms his letters is generally consistent and easy to read and interpret.

3. Ted returns to this image in the final poem of Howls & Whispers, where Frigga, the Norse goddess of fertility tends her cauldron.

4. Binah’s cheek is also one half of the face of the united Supernals (Binah-Chokmah) who, together with Kether (The Crown) form the head of Universal Man, Adam Kadmon, and represent the highest level of consciousness (MQ 47)

5. Binah and Chokmah live just such busy lives: as All Mother and All Father, Queen and King, Heroine and Hero, etc. in many world mythologies. The Cabbalistic theme of unbalanced energies, a fallen world, a bleeding hero, and a barren land which requires the union of Male and Female energies to restore it to fertility, similarly has many mythic parallels.

6. Such complementary male-female energies were part of Ted’s and Sylvia’s shared mythology. Sylvia wrote of Ted in her journal as “a god” whom she “had conjured” from the sea “for my earth goddess, he the sun, the sea, the black complement power: yang to yin.”. (SPJ 17 July 1957).

7. ‘Asgard for the Addict’, Ted’s review of E.O.G Turville-Petre’s, Myths and Religions of the North (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London, 1964) was published in The Listener, 19 March 1964.

8. In the Nibelunglied, the Rhinegold is the magical source of harmony. The lust of those who seek to own it, however, causes chaos and evil in the world of the gods. So, the World Tree dies; the Spring of Wisdom dries up; and gods and humans and their worlds are destroyed. Brunhilde and Siegfried, are the heroine and hero whose true love restores the balance so that the World Tree can grow again. But Siegfried, like all heroes, must first be tested to prove the strength and purity of his love.

9. Held amongst the Hughes-Sagar correspondence at The British Library.

10. Hughes-Sagar correspondence, 21 April 1977.

11. My own book, Ted Hughes: The Poetic Quest, examines in detail Ted’s attempts achieve this rebirth through the poetry and the Alchemy of Cave Birds, Remains of Elmet and River.

12. Elmet, published in 1985, includes some poems which were not in Remains of Elmet and it differs from the earlier publication in the order of poems and in the underlying purpose of the sequence (Ted discussed this difference in purpose with me in 1985, and in a letter to Keith Sagar that same year he wrote of the effort he was making to include “more of my own feelings (as distinct from my mother’s)” Hughes-Sagar correspondence, 28. Aug. 1985.

13. ‘Salmon Eggs’, R 120, THCP 680.

14. Robert Fludd, ‘Mirror of all nature and symbol of art’, Utrisque Cosmi, Vol. 1. 1672.

15. Sagar, K. The Laughter of Foxes, Liverpool University Press, Liverpool, 2000.

16. Hughes-Sagar correspondence, 11 April 1981.

17. Hughes-Sagar correspondence, 18 June 1998.

18. Baskin-Hughes mss. in the British Library, letter dated 15 August 1991.

19. Hughes-Sagar correspondence, 18 April 1998.

20. King Minos was murdered in his bath; Osiris was trapped in his coffin and thrown into the river; and the flawed King, Agamemnon, was stabbed by Clytemnestra as he stepped from the “ritual bath”, “taken by surprise, / naked, helpless”, as Ted described it in his version of The Oresteia (O 54).

21. Baskin-Hughes mss. The British Library.

22. Crowley, ‘Gematria’, 777, p. 28.

23. Ibid. p. 43.

24. SSN = Heline, C. The Sacred Science of Numbers, DeVorss Publications, Marina del Ray, CA, 1997.

25. Capriccio, Poems by Ted Hughes. Illustrated by Leonard Baskin, The Gehenna Press. Part of the final page of each copy reads: “Fifty copies of Capriccio were issued in the unsettled Spring of 1990”. ‘Superstitions’ in Capriccio varies in only a very minor way from ‘Superstitions’ in Howls & Whispers.

26. In Hebrew-Muslim tradition, Adam was created, cast out of paradise and died on a Friday. Loki, was the thirteenth god present when Balder, son of Odin and Freyja, was killed by the shaft of “spermy mistletoe” which Loki tricked blind Hoder into throwing. Balder’s death presaged the end of the corrupt world and the birth of a new, fertile and just world for gods and Man. Christ’s death, too, presages the Day of Judgment and the salvation of Mankind, and in Christian fable, his crucifixion took place on Friday the thirteenth. And Friday the thirteenth is, traditionally, the day on which Christopher Columbus first ‘found’ the New World of America and glimpsed a golden, “perfumed” paradise where people were naked, innocent and sinless. Bound by the chains of his own corrupt society, he brought that world slavery and death.

27. The Sefer Yetzirah (Book of Formation), the oldest known cabbalistic text, is believed to date back to the fourth century AD. Words chosen from it which have similar numerical values are considered to be explanatory of each other.

28. ‘Superstition’ “[OF, f. L super(stitionem f. stare stat-stand) perh. orig.= standing over in awe]”(COD), later came to mean “unreasoning awe or fear of something unknown, mysterious or imaginary, esp. in connection with religion”. (SOED).

29. Appropriately, in Hebrew and Cabbalistic traditions, 6 is the number associated with the Virgin, and 7 with Christ or the sacrificed god.

30. An epicanthic fold is a fold of skin which covers the inner corner of the eye. It is a common facial feature amongst Asiatic peoples.

31. Francis Yates traces this belief in detail in The Art of Memory (Pimlico, London, 1960), and Ted knew her work well.

32. Ibid. AOM 71.

Howls & Whispers text and illustrations. © Ann Skea 2005. For permission to quote any part of this document contact Dr Ann Skea at ann@skea.com