Birthday Letters and The Sorrows of the Deer

Ann Skea

Among Ted Hughes’ Birthday Letters manuscripts in the British Library are a number of old school textbooks in which Hughes wrote drafts of poems, most of which were eventually published in Birthday Letters. Hughes labeled these books S1 to S9, and the ‘S’ almost certainly alludes to Sylvia Plath.

In five of these books Hughes inscribed the heading ‘The Sorrows of the Deer’, and this was clearly the original title he chose for the Birthday Letters sequence. I have described elsewhere how the structure of the published sequence of Birthday Letter poems fits the pattern of a Cabbalistic/Hermetic journey1, and in every such journey, as Hughes wrote when discussing As You Like It in Shakespeare and the Goddess of Complete Being, “nothing is accidental”2. So, why did he choose that strange early title for these poems?

Hughes was, of course, well aware that Robert Graves identified the deer as being sacred to the Great Goddess. Chapter XIV of The White Goddess is titled ‘The Roebuck in the Thicket’; and according to Graves the Roebuck hides in a thicket of twenty–two sacred trees and its meaning is “Hides the Secret”3. Twenty–two happens to be the number of paths connecting the ten Sephiroth on the Cabbalistic Tree and the number of cards in the Major Arcana of the Tarot pack. Whether or not this was significant for Graves (he does not mention it), Hughes would have known it and it would have had significant for him in his final structuring of the Birthday Letters sequence. Writing to Keith Sagar shortly after the publication of Birthday Letters, he also identified himself with the Roebuck, saying that his decision to return to writing poems about his life with Sylvia, was precipitated by “ the huge outcry that flushed me from my thicket in 70–71–72 when Sylvia’s poems & novel hit the first militant wave of Feminism as a divine revelation from their Patron Saint” 4.

Hughes’ deep knowledge of Shakespeare’s work also meant that he would have come across the stricken, weeping deer in two of Shakespeare’s plays, Hamlet and As You Like It, in both of which the deer is linked to secrets and self–revelation. Of the two plays, the second is the most likely influence on Ted’s choice of title, but Hamlet’s reference to a “stricken deer” and its possible link with the Renaissance philosopher and Cabbalist Giordano Bruno may also be relevant.

Hamlet makes this bitterly ironic remark when, after watching a performance of his own play, The Mouse Trap, Claudius flees, fearing that his secret has been revealed:

Why, let the stricken deer go weep,

The hart ungalled play;

For some must watch, while some must sleep:

So runs the world away –

Hamlet (III, ii, 272–4)

Here, there is paronomasia between ‘hart’ and ‘heart’; and the word ‘ungalled’ suggests a heart untouched by anger but also, since a gall is a parasitic growth, a heart which has not been parasitically infected in some way. Taken together, these words suggest that Hamlet see Claudius as a parasite who has sullied the pure love his mother had for his father. So, the deer, which in mythology is one of the forms of the shape–shifting Goddess of Love, weeps.

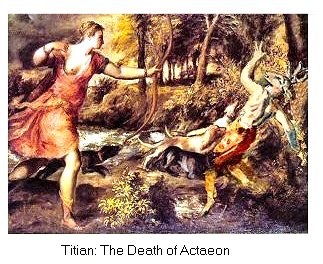

In a paper by Marianne Kumari, the ‘stricken deer’ is identified in several of Shakespeare’s plays, most notably in Hamlet, As You Like It and Twelfth Night5. She links these references to the life and work of Renaissance philosopher, mathematician, poet and Platonist, Giordano Bruno. In Gli Eroici Furori ( The Heroic Frenzies), Bruno describes the encounter between Actaeon (who is out hunting deer with his dogs) and the Goddess Diana:

… he sees a bust and face more beautiful than e’er was seen

By mortal or divine, of scarlet, alabaster, and fine gold;

He sees, and the great hunter straight becomes that which he hunts.

The stag, that towards still thicker shades now goes with lighter steps,

His own great dogs swiftly devour.

Explaining his meaning, Bruno wrote that Actaeon signifies the intellect, intent on the pursuit of divine wisdom and the comprehension of divine beauty.... “So Actaeon with those thoughts – those dogs – which hunted outside themselves for goodness, wisdom, and beauty, thus came into the presence of the same, and ravished out of himself by so much splendour, he became the prey, saw himself converted into that for which he was seeking, and perceived, that of his dogs or thoughts, he himself came to be the longed&for prey” 6.

Thus the myth of Actaeon and Diana becomes a metaphor for the passionate search by the heroic lover for Divine Eternal Truth, and Actaeon, the “stricken deer”, is the victim of the Goddess’s powers, but also of his own lack of self–knowledge. Birthday Letters, whilst resembling Bruno’s poem as a passionate and heroic expression of Hughes’ own search for truth, and as a record of his own negotiations with the Goddess, is also about seeking self–knowledge7.

In Shakespeare’s As You Like It, the character, Jaques, weeps for the wounded deer and the whole play is about distorted love. Here, the First Lord describes to the Duke a wounded stag and Jaques’ identification with the creature:

First Lord: The melancholy Jaques grieves at that:

…

To–day my Lord of Amiens and myself

Did steal behind him as he lay along

Under an oak whose antique root peeps out

Upon the brook that brawls along this wood:

To the which place a poor sequestered stag

That from the hunter’s aim had ta’en a hurt

Did come to languish; and indeed my lord,

The wretched animal heav’d forth such groans

That their discharge did stretch his leathern coat

Almost to bursting; and the big round tears

Cours’d one another down his innocent nose

In piteous chase;

Duke: But what said Jaques?

Did he not moralize the spectacle?

First Lord: O, yes, into a thousand similes.

Duke: And did you leave him in this contemplation?

First Lord: We did, my lord, weeping and commenting

Upon the sobbing deer.

As You Like It (II, ii, 27–68)

Hughes, in his own lengthy discussion of Jaques in Shakespeare and the Goddess of Complete Being (SGCB 101–8), writes of Jaques as “a gloomy wallflower”, the one character in the play who stands apart and sees the distortion of love which takes place all around him. So, the melancholy Jaques/Shakespeare weeps over the wounded stag, but he is also “a summarizing, unifying intelligence”, and “a kind of Hermes, the guide to the mysteries of the Underworld” who, symbolically, will restores harmony and “reassembles the whole, with ego and soul reunited in perfect love”8.

Hughes’ discussion of ritual Hermetic drama in this complicated analysis of Shakespeare’s As You Like It, is revealing. Early in the book, when he writes about Shakespeare and Occult Neoplatonism, many of the things he says apply equally to himself and to his own method of meditative visualisation and re–creation in Birthday Letters. Among the “archaic, magical, religious ideas and methods” which caught Shakespeare’s attention, he notes:

“The idea of as–if–factual visualization as the first practical essential of effective meditation (as in St. Ignatius Loyola’s Spiritual Disciples, as well as in Cabbala).

The idea of meditation as a conjuring, by ritual magic, of hallucinatory figures – with whom conversations can be held, and who communicate intuitive, imaginative vision and clairvoyance.

The idea of ritual drama for the manipulation of the soul.”9.

In a letter to two German translators of Birthday Letters Hughes wrote of his “sense of communicating with her [Sylvia Plath] directly, so to speak”10: and constantly throughout the sequence he conjures her and visualises her: “I see you”, “There you are in all your innocence…”, “Now I see, I saw, sitting, the lonely /Girl who was going to die”; “you returned…”. As he remembers their love and their lives together, he also created vivid images of himself, and of Plath’s father, Otto, “I glimpsed him…”, “You stand there at the blackboard…”. Yet, nowhere in the sequence does he name Plath. Everywhere, in spite of the detailed, remembered biographical details of their life together, he addresses her as ‘you’, a direct form of address, but also one which allows him to link her with the Goddess, because “Every living woman”, as he wrote, in his Vaccana Notebook11, represents a test which the Goddess sets for the human male. Every living woman embodies the Goddess.

Earlier in Shakespeare and the Goddess of Complete Being, Hughes had expounded his idea of active ritual drama as a spell – “a kind of sympathetic magic” – “working on the assumption (archetypal and instinctive) that a deliberately shaped ritual can reactivate energies on a mythic plane so powerfully that they can recapture and reshape an ego that seems to have escaped them on the realistic plane”12. This is exactly the sort of sympathetic magic (a self-revelatory, self-changing dramatic ritual) which Hughes was attempting when he wrote the Birthday Letters poems. Birthday Letters is a carefully structured, ritual re–enactment of love and loss in which Hughes himself (like Jaques) weeps for the wounded deer.

There are other indications that Hughes had a special interest in deer.

In 2003, when Daniel Weissbort was working on his book, Ted Hughes: Selected Translations, he told me of Ted’s fascination with a poem written by the Hungarian poet Ferenc Juhasz – ‘The Boy Changed into a Stag Cries Out at the Gate of Secrets’. It is possible that Ted had first seen this poem in one of the collections of Hungarian poetry which he began to acquire when his interest in Eastern European poetry was first aroused. One anthology of Hungarian poetry from the 13th century to the present day, translated into French, was presented to Ted by the Hungarian poet Janos Csokits in 1963. Ted certainly saw the poem in The Plough and the Pen: Writing from Hungary 1930-195613, and, as Daniel Weissbort records in his book, he thought the translation by Kenneth McRobbie “problematic”, so he immediately rewrote it “working with great concentration and at speed”14.

Juhasz’s poem can be interpreted in many ways, including as a version of Actaeon’s vision of the Goddess and its results (“human tears shone on his stag’s face” in Ted’s poem ‘Actaeon’ in his Tales From Ovid (THCP 937)); or even just as a poem about lost loved ones. If nothing else, Juhasz’s lines – “He stood over the Universe, on the ringed summit / there the boy stood at the gate of secrets” – would have caught Ted’s attention.

Also, among a number of books of Hungarian poetry in Ted’s library (now held at Emory University in Atlanta) is an anthology entitled: In Quest of the Miracle Stag: the Poetry of Hungary which was published in 1996.

Ted’s enduring interest in the sorrows associated with the Great Goddess’s shape–shifting, secret–hiding deer is clear. In 1978, when he and Seamus Heaney were collecting poems for The Rattle Bag, he wrote to his old friend Terence McCaughey, who was then Senior Lecturer in Irish Studies at Trinity College, Dublin, asking, among other things, “what is ‘The Sorrows of the Deer’?‘15. It turned out to be ‘The Deer’s Cry’, a prayer which St.Patrick is said to have uttered for protection when the 5th century Irish King of Tara laid a trap to try and prevent him from entering Tara to spread the Christian faith. In answer to his prayer, Patrick and his monks were given the shapes of wild deer with a fawn following them. The prayer, which takes the form of an invocation and a charm, became well–know, was set to music, and was and still is a popular hymn. Two of its verses are likely to have had special appeal for Hughes: one calls on the natural energies, the other is a traditional protective charm against malign influences:

4. I bind to myself to-day,

The power of Heaven,

The light of the Sun,

The whiteness of Snow,

The force of Fire,

The flashing of lightning,

The velocity of Wind,

The depth of the Sea,

The stability of the Earth,

The hardness of Rocks.

6. I have set around me all these powers,

Against every hostile savage power

Directed against my body and my soul,

Against the incantations of false prophets,

Against the black laws of heathenism,

Against the false laws of heresy,

Against the deceits of idolatry,

Against the spells of women, and smiths and druids,

Against all knowledge that binds the soul of man.16

Poetry, as Hughes said “is traditionally supposed to be magical”17. In invocations and charms like that of St Patrick’s ‘Deer’s Cry’, together with music and ritual, it connects us to the Otherworld of our instincts and imagination. The Deer, too, has a long history of shape–shifting. It ‘Hides the Secret’ of moving between our world and the Otherworld of the gods where, especially in Celtic mythology, it is closely linked to love and loss. It is therefore the perfect shamanic guide for a poet who seeks to communicate directly with a lost loved one, as Hughes does in the poetic drama of Birthday Letters. Hughes’ early title for these poems clearly acknowledges his debt to this magical creature.

Footnotes:

1. Skea, A. ‘Birthday Letters: Poetry and Magic’, https://ann.skea.com/BLCabala.htm.

2. Shakespeare and the Goddess of Complete Being, Faber, 1992 (SGCB) p.275.

3. Graves, R. The White Goddess, Faber, 1977. pp.54 and 251.

4. Reid, C.(Ed.), Letters of Ted Hughes, Faber, 2007. p.394.

5. Kumari, M. ‘Hamlet’s “stricken deer”: a pointed reference to Gli Eroici Furori and the execution of Giordano Bruno’, Academia.edu, 2017.

6. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/19817/19817–h/19817–h.htm #Third p.93. Hughes was very familiar with the work of Giordano Bruno.

7. Hughes owned copies of Frances Yates’ Giordano Bruno and the Hermetic Tradition and her Lull and Bruno, both of which describe Bruno’s writing about Actaeon. Whilst there are no volumes of in Hughes’ library now held at Emory University, there is a translation of Gli Eroici Furori in the Cambridge University library. Based on my own conversation with Hughes about Yates and Bruno, I am sure he had read Gli Eroici Furori in translation.

8. SGCB 113, 115 and 108.

9. SGCB 33.

10. Sagar, K. ‘Appendix XIV’, Poet and Critic, British Library, 2012, p.323.

11. Skea, A. ‘Ted Hughes’ Vaccanas’, Ted Hughes : Cambridge to Collected, M. Wormald, N. Roberts, T.Gifford (eds.), Palgave Macmillan, 2013. Also available at https://ann.skea.com/THVacanas.html

12. SGCB 107

13. Duczynak, I. and Polanyi, K.(eds.), The Plough and the Pen: Writing from Hungary 1930-1956, Translator: McRobbie, K., Introduction by W.H.Auden, who describes the poem as “one of the greatest poems written in my time”. The poem was not included in The Rattle Bag.

14. Weissbort, D. Ted Hughes: Selected Translations, Faber, 2006. p.24. Ted’s translation of Juhasz’s poem is published in full; and the first lines of a translation made by David Wevill for Penguin’s Modern European Poets series in 1970, are included in an Appendix.

15. Hughes to McCaughey in Reid, C.,Letters of Ted Hughes,Faber, 2007, pp.394–5. Hughes was looking for a copy of the Carmina Gadelica: prayers, charms, incantations, blessings, literary folk–lore and songs,gathered in the Gaelic speaking regions of Scotland between 1860–1909, edited and compiled by Alexander Carmichael, Oliver & Boyd, Edinburgh, 1900.

16. The full prayer and a discussion of its origins and use can be found by searching for ‘St Patrick’s Breastplate’ on Wikipedia.

17. Hughes, T. The Critical Forum, Norwich Tapes, 1978. Transcript at https://ann.skea.com/CriticalForum.htm

© Ann Skea 2022. For permission to quote any part of this document contact Dr Ann Skea at ann@skea.com