Once the Visionary Eye is open, the Revelation of Truth becomes possible. Such a revelation is sudden, involuntary, shattering and transforming. The fortress of the individual self is destroyed and a new being with new understanding is born.

In Ted’s discussion of ‘Orghast’, the experimental drama he and Peter Brook created in 1970 - 71, he described the way in which we all may experience moments of revelation through sound and music: how, sometimes, we are aware of some extraordinary, elemental quality which seems to connect us with “a spirit, a truth under all truths”1. And he described such an experience as being at once utterly beautiful yet also harrowing and terrible.

If this is so for those who are uninitiated in any spiritual way, then it is most powerfully so for those who have sought enlightenment and have followed the rigorous paths towards self-knowledge. For them, as the testaments of religion, mythology, Cabbala, Alchemy and other mystical teachings disclose, Divine revelation results in conversion, transmutation, metamorphosis: the transformation from a worldly being to one filled with other-worldly, spiritual energies2.

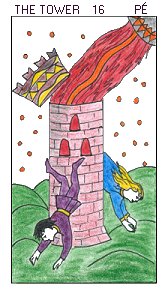

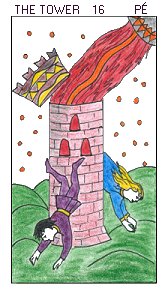

The image of the lightning-struck tower which is shown on the Traditional Tarot card for this Path of the Tower (the Path of Pé = ‘mouth’ ) is an apt symbol for Divine revelation. Appropriately, lightning does not just strike the tower, it flows between the heavens and the interior of the tower, thus connecting the Source with the Divine Spark within the material, earth-bound body. The crown of the tower, like the crown we humans metaphorically award ourselves for our rational abilities, is toppled to one side by this supremely non-rational (yet natural) event. And two human bodies fall to earth amidst a shower of golden spheres, which, in some Tarot packs, are shaped like the Hebrew letter ‘Yod’ to represent the Spirit of God. So, symbolically, at the moment when the lightning bolt of Truth joins the energy of the Divine Source and the Divine Spark within the initiate, human consciousness is freed from all material illusion and all bondage, the individual ego is cast down, and division is overcome. If the initiate’s care and preparation thus far have been adequate, a new, whole, naked and vulnerable spirit is born, phoenix-like, from the fires.

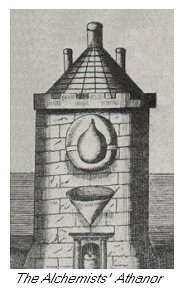

Fire is the Mother element associated with this Path. And, the fact that the tower on the Traditional Tarot card looks very like the Alchemical athanor or furnace, as it is depicted in many Alchemical manuscripts, is a further reminder that there are both generative and latent fires within the initiate on this Path3, and both are essential to the end result. The Alchemist knows that on both the practical (chemical) level and the spiritual level only carefully prepared, pure materials should be put into the vessel which is placed in the athanor. He or she also knows that the chemical reaction within that vessel, once begun, may be violent and explosive. So, continuous patient and precise attention is critical to the success or failure of the whole quest4. And the image of the lightning struck tower is not only a metaphorical representation of the final ejaculation of the pure spiritual gold of the soul from imprisonment in the base matter of the body, it is also a graphic warning of the sort of disaster which will result from even the smallest degree of carelessness or imprecision in the Great Work.

Clearly, too, there is phallic symbolism in this Tarot card imagery. This is related to the double meaning of the word ‘ejaculation’, which refers both to the sudden release of generative sperm in a sexual climax; and to a sudden involuntary cry, for which the mouth (which is the Hebrew name for this Path) is essential. The Cabbalistic interpretation of the word Pé, however, encompasses both the Divine mouth from which comes the Word, the breath of life, Truth and Grace but also destruction and death; and the human mouth through which the one enlightened by Divine revelation may transmit Truth, wisdom and words of blessing to others.

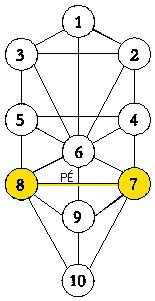

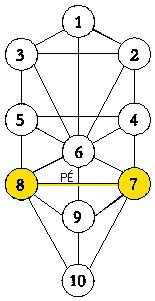

At each end of the Path of Pé, which links the Pillar of Form to the Pillar of Force, are the Sephiroth Hod (8) and Netzach (7): Splendour and Endurance; Logic and Feeling. The Virtues of these two are, respectively, Honesty and Truthfulness; their Qlippoth are Rigidity and Habit. Their energies complement each other and both are linked by separate Paths to Tiphereth (6) at the heart of the Tree, making a triangle which reflects the Divine Triangle at the top of the Tree. Numerologically, the powers of the Sephiroth 6, 7 and 8 are greatly magnified on this Path, which in Tarot is numbered 16 (the powers of 6 added to the powers of 10; also, 1 + 6 reduces to 7); and in Cabbala is numbered 17 (the powers of 7 added to those of 10; also 1 + 7 reduces to 8). An additional Cabbalistic number for this Path is 80: 8 multiplied by the powers of 10.

This reverberation and magnification of the powers of 7 (the number of Venus, Goddess of Love), 8 (the number of Mercury – Lucifer, psychopomp or light-bringer) and 6 (the number of The Way) makes the achievement of balance on this Path especially difficult. Metaphorically, the initiate has the support of these two most powerful gods but both have a double nature and both can be jealous, vengeful and tricky. In addition, the astrological sign which governs this Path is that of Mars, God of War, whose energies are turbulent and dangerous, but who may also provide the initiate with the courage and determination which are necessary here. Success or failure is sudden and dramatic; and failure may result in the imprisonment and enslavement of the initiate5, and in sacrifice and death. In these circumstances, the balancing energies of Tiphereth – The Way (6) – magnified as they are on this Path, are essential if the initiate is to succeed.

War is an important sub-text in ‘Your Paris’ (BL 36 - 38), which is the poem on this Path of the Tower in the Atziluthic World: but the archetypal pattern which shapes this poem is Alchemical.

Briefly: for the spiritual Alchemist, there are two essential and basic generative forces in the body and these are known as ‘Sulphur’ and ‘Quicksilver’. Sulphur is regarded as male: it is heavy and coagulating, hot and dry, and it contains the inner, fixed gold of the Soul. Quicksilver/ (Mercury) is regarded as female; it is mobile, volatile, sometimes corrosive, and it contains the Vital Spirit, the ‘germ’ of the Sun. The coalescing and cleansing powers of both Sulphur and Quicksilver are necessary for the progressive purification of the ‘Base Matter’ of the body and for the ultimate revelation and release of the pure gold Spirit/Soul.

Ted, in ‘Your Paris’ is Sulphur: Sylvia is Quicksilver. His vision of Paris in June 1956 was still contaminated with wartime horrors; hers, he imagined, was formed by American writers like Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Miller and Stein, and by artists’ representations of the city. He was dog-like, nose-to-earth, “pondering”, ponderous, solid: she, an airy, mercurial glitter of exclamations and cries. And he heard the “contrabasso counterpoint” beneath her “ecstasies”. Neither was yet able to see the truth beneath their illusory interpretation of the world.

Legally bound together as husband and wife, the couple had now, as in an Alchemical reaction, to work together to produce a balanced, stable, harmonious and productive union. As two young people with very different temperaments and from very different worlds they began their new partnership in (appropriately) the “Hotel des Deux Continents” in Paris. And the individual and vastly different ways in which they saw Paris is like that first, impure, mixture of Sulphur and Quicksilver which the Alchemist measures carefully into an hermetically sealed flask and places in the fires of the athanor.

Just as the Alchemist may need to repeat this process many times before the Alchemical goal is achieved, Ted and Sylvia still had much to learn. In this Atziluthic World, Ted shows them as unskilled in understanding and facing reality. They are deflected from reality (and deflect reality) by camouflage and self-deception, so that they make false appraisals and false interpretations of the world and of each other. Sylvia hides her fears and protects herself with verbal anaesthetic. Ted is dog-like, his wolf-energies lulled by love into a desire to “humour” Sylvia, but also blocked and “scorched-up” by the barrage of words, “exclamations”, “cries”, and “ecstasies” by means of which she prevents herself from examining her innermost feelings. And it is interesting to note that just as in Alchemy, where the purest Sulphur and the purest Quicksilver each retain a germ of the other within themselves, Ted’s Sulphurous vision of Paris was coloured by his quicksilver imagination – by carefully “rehearsed” scenes based on what he had heard and read of its war-time history; and Sylvia’s Quicksilver vision of the Paris was something she wanted to draw – to coagulate and fix, just as Sulphur coagulates and fixes.

Ted’s imaginative vision of Paris, however, was Sulphurous in its expression. For him, Paris was a bullet-scarred place of “nightmare” in which, with a dog’s reputed psychic sense (another Quicksilver/Mercurial characteristic) he became a “ghost-watcher”, one who smelled the methane “stink” of fear and of old graves, and who tasted the dregs of terrible secrets beneath the surface civilities. He saw only the Sulphurous underside of things, and even a sunny pavement was darkened for him by what he “read” as bullet scars in the wall above it. His “perspectives”, he notes in the poem, were so “veiled” by fumes from the pit that he was “not much ravished” by his view of the roofs.

Sylvia’s quicksilver vision of these same roofs, however, was that of “les toits” – something from a light-filled impressionist painting. War, to her, seemed to be nothing more than an “aesthetic touch” to that painting: something like the allegedly “proleptic” mark on a Picasso portrait of Guillaume Apollinaire6. She called Ted “Aristide Bruant”, after the romantically debonair figure in a famous poster by Toulouse Lautrec (and there is a germ of Sulphur here, too, because Bruant, who was a cabaret artist, was famous for his corrosive wit, his excessive drinking, and for degrading and insulting his audience). And it seemed to Ted, then, that everything Sylvia saw was given added texture and colour by her words, her “immaculate palette” of cries, a “lingo” peculiar to her. What Ted did not see at that time – what all that quicksilver camouflage actually prevented him from seeing - was the real corrosive terror, pain and uncertainty in Sylvia herself: a torture which both burned and “sealed”, flayed and congealed (just as a chemical mixture of mercury and sulphur would do if it were inside her), so that her spirit “hung waiting” in agony in the “underground” chamber of her body.

Only years later, when Ted read Sylvia’s journals, did he learn that three months before their honeymoon trip to Paris, Sylvia had written a passionate and agonized letter to Richard Sassoon after his rejection of her. In her journal, she described her physical and mental distress in terms of “internal bleeding”: “day by day”, she wrote, “it drips, and gathers, and congeals” (SPJ 6 March 1956). Later that same month, she had gone to Paris expecting to meet Richard, only to find that he had gone away. Her letters to him lay unopened on his desk.

Sylvia, surely, must have walked Paris with Ted with all these recent events fresh and painful in her memory. She must have known that at any time, around any corner, they might come face-to-face with Sassoon and a “final revelation” of her secret might occur. But she masked all this with the “gushy burblings” which she “excused” with “practised lips”. So, Ted “yawned and dozed” and watched the way in which she transformed real things, including living things like himself, into fixed and manageable images on paper. Significantly, he describes her doing this “as by touch”, as if she were blind and did not physically see these things. And, indeed, like the writing of poems and stories7, drawing was Sylvia’s instinctive way of trying to calm the fears which drove her: she found it “anaesthetic”, but it was not yet a true way of seeing, understanding and controlling the energies of her world.

Another poem, ‘Paris 1954’, which begins the sequence of Howls and Whispers, is set two years earlier than ‘Your Paris’ but it also deals with the sort of cataclysmic and life-changing event which is associated with the Path of the Tower. The focus in ‘Paris 1954’, however, is on a “young man” who will unwittingly be sacrificed to some terrifying, powerful and soul-destroying energy. This horror has lain in wait for him and comes to him, in the poem, “in the likeness of a girl”. Yet, because it presents only the male perspective, this poem lacks the balance of ‘Your Paris’. There is no sense of the girl’s own unwitting role in the drama or of her own pain and sacrifice: she enters the poem only as the vehicle for this horror – this “scream”. So, in effect, ‘Paris 1954’ is like a solitary howl of pain and it does not fit the established pattern of the shared journey which is an essential part of Birthday Letters. ‘Your Paris’, on the other hand, with its careful mixture of untempered, unpurified male and female elements, is much better suited to this particular Atziluthic Path in the Birthday Letters sequence.

Whilst the underlying pattern in ‘Your Paris’ is strongly alchemical, ‘Grand Canyon’ (BL 96 - 08), which is the poem on this Path in the Briatic World, is shaped by Ted’s own synthesis of Cabbalistic beliefs and cosmic creation myths. On this Path where Truth is revealed by sudden Divine intervention, the fine interface between human and Divine, illusion and Truth, past and present, life and death, is suggested throughout the poem by fragile, protective membranes. A meniscus tops a “brimming glass” of orange juice; uterine membranes surround the six-week-old foetus; “eardrums” are subjected to unlikely “stagey tales”, but respond, too, to genuine reverberations of canyon thunder; a water-bag protects cool water from desert heat; and “body-sacks” are assailed by physical and mental “shock-waves”. Most important of all, is the drum-skin membrane from which came “PAUM!”, a sound which “swallowed” “everything” and which echoed down the years to recur “at odd moments” – still as vivid, as “shaking”, and as close, as the voice of the daughter whose living presence linked that first drumbeat with the moment when Ted wrote its sound into this poem.

Grand Canyon, as a geographical location and as a poem, brings together all the Mother elements (Fire, Air, Earth and Water) in a place and a poem which join past to present. The canyon itself is an elemental place shaken with “thunder and lightning”, a place of myth and story; a place so vast that normal perception is disturbed and the senses reel. And in Ted’s poem, it is “America’s Delphi”, a chasm close to the hellish fires of the underworld, and the place of “America’s big red mamma” from whose body everything around was created and who, like the Earth Goddess, might provide Sylvia with “a sign” or a prophecy.

Birth, in particular, is a Mystery which is threaded throughout this poem. Sylvia is preparing to give birth. She was six weeks pregnant with Frieda when she and Ted visited Grand Canyon, and she was also pregnant with the words which soon, at Yaddo, she would shape into a creative rebirth in ‘Poem for a Birthday’. At the beginning of ‘Grand Canyon’, Ted shows her balanced precariously on the rim of the Goddess’s realm. Her orange juice and her foetus both contain an essence of life, both push against a thin membrane, and both are carried by Sylvia with protective care. Even the suspended water-bag repeats this image of a carefully carried membranous container full of the essence of life. And the way in which Ted has used the personal pronouns ‘her’ and ‘you’ in relation to “foetus”, “quaking echo-chamber” and “daughter”, merges together the identity of all the women – the Goddess, Sylvia and the child.

Ted’s image of the “mamma” canyon lying open to the caress of the sun is sensual and erotic, but the “afterglow of her sensations” is also linked in these lines to a birth. This particular birth, however, was not easy: “something”, it seems, as in the myth of God’s creation of Adam from Earth’s red clay, had been “hacked” from her as if from a “quarry”, but (as in the myth, where Adam has still to be animated by God’s breath) whatever was born was stone-like – a “sculpture”. It is hard not to remember, here, Sylvia’s own creative agonies at that time, and that she described the stories she was producing as “pretty artificial statues” (SPJ 16 Sept. 1959) and, even after ‘Poem for a Birthday’, called her poems lifeless - ’stillborn’ (SPCP 142).

Even the cougar hunter, in Ted’s poem, carries the essence of life. His performance may have been “stagey” and joke-less but his words still held the faint vibrations of untamed, elemental energies, and these “rippled” over the foetus which (because of Ted’s use of ‘her’) may be Frieda and/or the gestating spark of the Goddess within Sylvia herself. The cougar hunter’s “translation” of these primitive energies into a dollar-making show, however, was not what Ted and Sylvia had come for.

What they did come for (and Ted describes their journey in terms of the mental and physical “labour” which they have endured and calls it a “pilgrimage”) was a “sign”, a “word”, a “blessing”. And the drum-beat which brought them this takes us immediately back to Delphi and the Mysteries associated with the rebirth of Dionysus as Iacchos. During the celebration of these Mysteries, the sound of the tympanon (a drum-like instrument “with a voice like thunder”) was know to all initiates to announce the moment of Epopteia – the moment when ineffable things were revealed8. It announced the birth of the Divine Child, the appearance of the god or goddess, and the renewal of life. It was a moment of thunder and lightning (or enlightening) which brought together Heaven, Earth and the Underworld.

Lightning in most mythologies comes from the Sky-Gods: thunder from the Underworld. In ‘Grand Canyon’, heaven, earth and the underworld come together in “miles-high ramparts” and canyon depths; “sky-vistas”; and a dark road starred with “beer-can constellations” from which “thunder-beings” sweep “against” and “through” the travellers. Yet the drumbeat “PAUM!”, which reverberates through the last part of the poem, is far more powerful than all the rumblings and reverberations, ripples and “shock-waves”, which have disturbed the various membranous interfaces in the poem so far. To Ted, it was the summoning voice of the canyon-Goddess. But the letters by which he actually “made a note” of this sound9, and the way in which the poem brings together all the cosmic energies and the Mother elements, suggest other creation mysteries beside those of Delphi and Eleusis.

Ted’s word, ‘PAUM’, embodies ‘Aum’ or ‘Om’, which, for Hindus, is a sacred word. In Hindu mythology, it is the sound of the Lord Shiva’s drumbeat: a sound which signals the dance, Tandava, by which one cosmic period of the world disappears, is absorbed into the Absolute, and another begins. In the form of Nataraja, Lord of the Dance, and surrounded by cosmic fire, Lord Shiva destroys and creates the world. He is Lord of Demons and Teacher of Truth. His dance is ecstatic, so he was confused by the Ancient Greeks with Dionysus. And he is ithyphallic, represented everywhere in the Hindu world by the Lingam. All of which attributes make him an appropriate figure here on the Path of the Tower10.

Aum, too, is ‘Pranava’, the ‘unstruck sound which accompanies the vibration of every atom and particle in the universe. It is the manifest sound of the Supreme Being whose breath destroys and creates the cosmic vital force and keeps it in motion (and, so, is synonymous with the “Word” of the Christian Scriptures). And it is the bridge between the infinite and the finite. In Hindu belief, as in Cabbalistic and NeoPlatonic belief, the world is patterned by cosmic vibration and the Divine Spark (or Atman) is the True Self within us which is released from the material illusory world by the Divine revelation of Truth. ‘Aum’ brings the human into harmony with the Divine. It encompasses all levels of consciousness (waking, dreaming, and dreamless sleep) and all states of being (rational, imaginary, conscious, unconscious, ecstatic and blissful). Aum (or Om) has resonance in many religions and in many languages. It is part of ‘Amen’ and of the Buddhist ‘Hum’, and it is the root-syllable of words like ‘omnipotent’, ‘omnipresent’, ‘omniscient’ and, appropriately here, ‘omphalos’.

PAUM! incorporates AUM into the drumbeat of Ted’s poem, and with its repetition he creates a mantra containing the most powerful syllable and sound associated with the Absolute - the All. No wonder, then, that it “swallowed” everything, destroyed “memory”, wiped out time and “suspended” everything and everyone (again, ‘her’ in lines 62 and 63 encompasses the Goddess and the unborn child) in its vibrations.

Symbolically, whilst this was happening, the water-bag, which they had carried with them un“broached” on their pilgrimage as a precautionary life-support measure, was stolen. No such material support is possible in the world of the spirit. Truth strips away all such illusions and leaves the soul naked and vulnerable. “Nothing is left”.

Nothing was left, either, of the world Ted tried to recreate as he wrote the poem. Sylvia was dead. And although he does not name her, he links her again, in a single ambivalent ‘you’, with the mamma-Canyon to which he “never went back”, so that it seems that both “are dead”. Only the powerful vibration of that drum-sound returned at “odd” times, unannounced, to dissolve time and to re-awaken him to the imminence of Truth. This was the revelation which Ted and Sylvia once shared: that Truth exists “close”, “itself” and Absolute, like the vibrations of a voice.

Once again, in the penultimate line of the poem, Ted linked the personal pronoun ‘your’ with ‘daughter’ in such a way that Goddess, mother and child are merged, and other interpretations of this lines are made possible. Frieda was Sylvia’s daughter and also Ted’s, so he could describe the sound of her voice as “ours”. But everything created belongs to the Mother Goddess: Frieda, Sylvia, and Sylvia’s poems, all are hers; and throughout Birthday Letters Sylvia has represented the Goddess, as a daughter would. So, “ours” may be understood as a queenly claim by the Goddess to Sylvia, to her poems, and also to the distinctive voice that is heard in Sylvia’s poems. All of these possibilities are joined by a dash to that final PAUM! which ends the poem, and dissolves everything - people, places, time, and everything in and about the poem – in its vibrations11.

On the fourth of May, 1962, Sylvia wrote to her mother enclosing colour photographs of herself, Frieda and Nicholas which were taken amongst the daffodils in their Court Green garden. One of these photographs (SPJ opp. p. 517) exactly fits Ted’s description of the “picture” in ‘Perfect Light’ (BL 143), which is the poem on this Path in the World of Yetzira. Even in a black-and-white reproduction, the picture glows with light: in colour, the golden glow of the daffodils and sunlight must have made it even more remarkable.

Sylvia wrote that the photographs were taken on Easter Sunday, a day with the most ancient connections with the Spring equinox and the Mysteries of rebirth and renewal. Easter is said to be named after the Anglo-Saxon Goddess of Spring, Eostre; but ‘Eos’ was also the Ancient Greek Goddess of Dawn. For the Greeks, too, the Spring equinox was associated with the myth of Persephone’s return from the Underworld. And in the Mystery cults at Delphi and Eleusis it was the time of the birth (or rebirth) of the Divine Child, as it also was in the cults of Attis, Osiris and Orpheus.

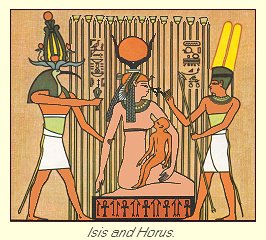

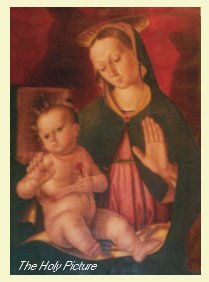

Ted’s image of Sylvia in his poem combines all these ancient associations. She, like Eos, glows with the “perfect” golden light of a new dawn. She is “like a daffodil”, the flower which, like Persephone, returns from the dark Underworld of the earth and heralds the onset of Spring12. And, in her arms, is her “new son”. The “innocence” of Mother (Ted placed this word carefully so that it has a capital letter) and child, and the iconic grouping – “as in the Holy picture” – is an archetypal image which has existed for thousands of years13.

Complex as such a variety of mythological association may seem, all are relevant to the combination of rebirth and the sudden revelation of Truth which is associated with the Path of Pé. And Ted’s poetic “picture” of Sylvia and her children seated on the newly blossoming earth, bathed in pure sunlight, and radiant with love not only reflects all these associations but also is a beautiful expression of the illumination which is part of the Glory of Hod on this Path.

Caught in the instantaneous click of a camera shutter, this moment of illumination is suspended in time. Neither ancient “knowledge” from the “hill fort” on which Sylvia sits, nor the weighty import of her “next moment” reach this picture. In it, Sylvia is child-like again. It is her “April”, her Spring, and everything has “melted” in this Easter dawning of “perfect light” – a light which, in Cabbala and Alchemy, marks the sudden appearance of the pure Mercurial Spirit, the herald of the final stages of the journey14. In Alchemy, this Spirit is called ‘the golden flower'15; it is the mystical ‘transforming substance’; and the light which accompanies its appearance is called the ‘aurora’ (the dawn) or, as in the title of one of the oldest texts, the ‘Aurora consurgens’ (the Dawn of Wisdom, which is the Wisdom of God)16.

Another common Cabbalistic image also makes sense of Ted’s reference to “ the knowledge” which failed to reach the picture from inside the moated hill-fort. There is a pre-historic hill-fort in the garden at Court Green where those April photographs were taken, but in Ted’s poem it is not the fort which fails to reach the photograph, but the knowledge “Inside” (the capital letter is significant) it which fails to reach the picture. Ted’s choice of words in these Birthday Letters poems was never careless, so we can assume that he chose the word ‘picture’ deliberately, thus extending the meaning of his words beyond a reference to a specific photograph. Whatever actually lies inside that hill-fort at Court Green (other than the earth itself) can only be remains on which archaeological knowledge might be based. It makes no sense to suggest that such knowledge could ever have been part of the photograph. On the other hand, Cabbalistic and Alchemical knowledge is frequently represented as a fortress (or a moated hill), around which the Truth-seeker must journey. What is inside that fort is Cabbalistic knowledge, knowledge of The Way; and ‘Our Mercury’, too, is there, for knowledge alone will not bring Wisdom: Mercury is the mediator, the ‘transforming substance’, the channel for the lightning flash which will join the Divine Source to the Divine Spirit, destroy the tower of illusion, and reveal the Truth.

So, if we look at the bigger picture, one which includes Sylvia’s quest for her true Self, and one which takes into account the position of this poem on the Cabbalistic Path of the Tower, the moment of pure illumination and love which Ted describes in his poem is indeed a moment which no amount of knowledge could provide. It is a moment which reveals the supreme, harmonising power of love; a moment in which the energies of Mercury and Venus on this Path are totally balanced; a moment of perfect light illuminating The Way.

It must be remembered, too, that in this bigger picture, Sylvia’s quest was undertaken through her writing; and this particular Path, in the World of Yetzirah, is where the patterns formed so far (both rational and non-rational) are crystallized. If the word ‘moment’ is taken to embody movement, weight and importance, Sylvia’s “next moment”, in her poetry was the moment in which her Ariel voice suddenly emerged in ‘Elm’. Sylvia had spent the early weeks of April 1962 writing ‘Elm’: and the “picture” of Ted’s poem is set in April17. That sudden emergence of Ariel (a pure Mercurial Spirit in every respect, and herald of Sylvia’s poetic rebirth) was a result of Sylvia’s long inner battle from which she, like a weary “infantryman”, had carried the heavy load of her wounded Self: and her “no-man’s -land” was “the strange limbo of ‘gestation / regeneration’” about which Ted wrote in ‘Sylvia Plath and her Journals’ (WP 180). Nothing of all this reached that picture of perfect light in Ted’s poem: all was “melted” in that flash of illumination.

Illumination, whenever it occurs, is sudden (like a lightning flash), momentary and transforming, but it does not ensure the successful completion of the quest, Often, as in the Yetziritic World in which this poem occurs, there are still many Paths yet to be completed; new revelations may still be necessary; and infinite care and attention must be constantly maintained.

Sadly, in both the literal sense and in the metaphorical sense of Revelation which is appropriate to this stage of the Cabbalistic journey, this was Sylvia’s “only April on earth” amongst her daffodils. Her moment of perfect light was a moment of revelation and it did herald a rebirth, but this was not the end of her quest, and her death in February 1963 prevented its completion. Yet, by omitting any punctuation at the end of line 5 of his poem, Ted linked Sylvia’s ephemeral moment “on earth” amongst her daffodils with that of “any one of those daffodils” and, thus, he put his “picture” into the context of the continuous, cosmic cycle of death and rebirth which dominates this Path, and by doing so he gave it universal meaning.

In ‘The God’ (BL 188-191), which is the poem on this Path in the World of Assiah, Sylvia’s internal battles fill the poem, but the no-man’s-land from which she brings her wounded Self is the desert (the “Sahara”) of the Cabbalistic Abyss. This Abyss, Daat, like the no-man’s-land of wars, is a place of shells: a dark place in which only the fragments of failed creations exist. It is also the desert place, outside the World of Light, to which Fallen Man was exiled and from which the human soul, the Divine Essence of Self, must be retrieved. On the Cabbalistic Tree, it separates the Divine triangle of Sephiroth 1, 2 and 3, from the rest of the Tree and the Cabbalistic pilgrim must cross this desert-Abyss at the start and at the end of the journey. Importantly, on the Path of Pé, the energies of its two Sephiroth (Hod and Netzach) are mediated and balanced by those of Tiphereth (6 – The Way) which, itself, is linked by the High Priestess’s Path (the Path of Gimel – the Camel) across the desert-Abyss to Sephira 1 at the apex of the Tree.

All these links, and the energies associated with them, are an essential part of the imagery Ted used in ‘The God’. At the same time, the poem is very much part of the World of Assiah (itself a World of Shells), where the Qlippoth of Sephiroth 7 (rigidity and false ideology) and 8 (habit, routine and the repetition of old patterns) are clearly demonstrated.

At this point in the chronology of Birthday Letters, Sylvia’s journey was over. And these last poems, as well as being part of Ted’s attempt to understand all that happened, are like laments for the great endeavour in which he and Sylvia had invested so much but which had failed. At the heart of ‘The God’ is another Holy picture but now it is not that of Mother and infant, but a pièta – a mother grieving for her dead child. And this image conveys the grief of both Sylvia and Ted at the loss of Sylvia’s newborn Self.

Yet Ted’s love, as well as his grief, shine through the rhythms of ‘The God’, uniting the disparate thoughts and emotions, and balancing the fiery Mercurial images and energies which drive it. And love, in a different way, is shown to underlie all of Sylvia’s struggle for rebirth.

From the beginning, “like a religious fanatic”, Sylvia had looked for something or someone to receive her love. She was “possessed”, as Ted wrote elsewhere, by “a genius for love” which she “didn’t quite know how to manage” (WP 162). Sylvia’s father, clearly, had been the god on whom she had bestowed her love, but after his death she was “without a god”, although she still wrote about him in god-like terms. In notes she wrote in her journal in December 1958, after sessions with her psychologist, she analysed and recorded her ideas about god; and about “Love”; and about her writing. All that she wrote then is pertinent to Ted’s description of her in ‘The God’.

In particular, Sylvia wrote that what she wanted in “Love” was something which “was inside a person”: it was something “strong and loving in body and soul” which would make you “perfectly happy with them if you were naked on the Sahara” (SPJ 12 Dec. 1958). She was as rigid in her requirements for love as she was about her writing: she knew what she wanted, she said, and she did not compromise. And she compared her approach to that of others who went to extreme measures for the sake of love, and suggested that her own approach was harder, even, that that of an ascetic like St. Theresa of Avila, whose autobiography she was reading at that time (SPJ Appendix 10. 44 [a-b]). Writing, too, she described as “a religious act”, and she was very clear about her desperate need to write and her fear of failure: but she was very unclear about what she wanted to write, listing numerous suggestions for topics, characters’ names, fragmentary ideas and story-outlines.

“Wanted to write?”, Ted asked in ‘The God’. “What?”, Why? What was it “within” that demanded that its tale be told? Sylvia did not know the answer: only that like all writers “The story that has to be told” was her God, even though He/it seemed to be “dead” or “non-existent”. She was, indeed, in a desert of emptiness and torment, like a religious fanatic. And Johnny Panic, like an ascetics’ idea of God, was her own creation, drawn from her “emptiness” just as “goblins” are sometimes “sucked” from the ascetics’ sterility by the vacuum in which they choose to exist18.

To this God of Panic, Sylvia offered “verses” (a word which implies their emptiness and lack of value). Nevertheless, the tears of pure, instinctive emotion which she “dropped” into these verses became, “after dawn”, a “crystalline spectrum”: as if, in Cabbalistic terms, Sylvia’s true heart-felt emotions remain, like “dried” desiccated “salt crystals” (the “sweat” of her labour in the desert Abyss) in the verses which eventually led to her rebirth. There they still are, like “oblations” and “little sacrifices” made to an unknown god.

But those little sacrifices, it seems, were not enough: even though the position of the word “soon” joins them (after a break which suggests a period of time) to the sacrifice of the “dead child” at the heart of the next 10 lines of Ted’s poem, thereby suggesting their role as precursors to this terrible scene. Sylvia’s rigid, self-imposed regime of struggle towards self-expression was a labour of love, but it was self-focussed and fanatical, and it was accompanied by her agonizing fear of failure. She swung between joy at each success and despair at each failure. And in this unbalanced battle, in the dark “night” of her uncomprehending, unwise, unenlightened state, from that same agony of pure emotion which produced her tears came the “silent howl” – ‘O’-shaped, mouth-shaped, moon-shaped and tear-seeded – from which her moon-idol God emerged.

Sylvia’s ‘Poem for a Birthday’ (SPCP 131-137) seems to foretell this god’s appearance. In it, Sylvia enters the earthy Underworld darkness of the Moon Goddess, Hecate, - the “Lady” whose “moon’s vat” will help her “become another”, and in whose dark “bower at the lily root” a god will metamorphose to supervise the “witch-burning”. Sylvia prays to Hecate, “Mother of beetles” (who is also Earth Goddess, Queen of the Underworld and Goddess of the Dark Moon), for release, and vows to emerge from the fires robed in light. Finally, in ‘The Stones’, Love is the “bald nurse”19 who reconstructs Sylvia as a vase for the “elusive rose”, which is a common mystical symbol for the Divine Spirit. It is love like this which, in Ted’s poem, is shown by the woman who nurses the dead child; by Ted nursing Sylvia through the gestation of her new poetic Self; and by Sylvia, nursing that buried Self, which is “human” but dead, withered, and as “corrosive” as “Phosphorous” (a natural, element, poisonous if ingested but which, when exposed to air, spontaneously ignites and burns with a cold, luminous, moony and mercurial light).

The fiery idol, the moon, and the dead child, all are shells – reflectors of light with no light or life of their own. Yet from these, in ‘The God’, a child is born: and Sylvia feeds it like a mother. Its mouth-hole (another ‘O’-shaped, moon-shaped, howl-shaped image which is given a voracious unpleasantness by Ted’s choice of words) stirs, but its food is blood. Sylvia’s nipples “ooze” blood, and this “drip-feed” contaminates (by its proximity in Ted’s line) “Our happy moment” although, at the time, they were joyfully unaware of the true nature of this ‘child’.

The child, this “little god” in the “Elm Tree” (the capital letter on ‘Tree’ suggests the Elm’s symbolic status as a tree associated with death, magic and the Underworld), can only be Ariel, whose appearance both Ted and Sylvia happily recognized as the revelation of Sylvia’s true poetic voice. Ariel was, indeed, ‘Our Mercury’, the pure Mercurial Spirit released from within Sylvia. But whilst Mercury/Hermes is the guide of the Soul, god of eloquence and messenger of the gods, he is also psychopomp – the conductor of Souls through the Underworld; and he is as loved by Hecate, Queen of the Underworld, as he is by Zeus, his father. So, he may carry messages from either; and since he is also an eloquent liar, skilled in all kinds of magic and enchantment, and a clever trickster, he can never be trusted.

Sylvia, in ‘The God’, hears his “instructions” in her sleep – “glassy-eyed” as if mesmerised by his music. And even awake, she remained under his spell: writing automatically, “making” a new, bloody “sacrifice”, unable to explain how she did it or why, or “who” prompted it. Meanwhile, the “little god”, Ariel-Mercury, laughed and roared in the dark orchard (a place from where one might expect only dark fruit could come).

So, at her desk, Sylvia fed her little god with whispers,

drumming rhythms with her fingers20,

and hearing the echoes of “sea-voices” in the shells of her

Winthrop childhood. The “effigy” she gave to Ted, the

picture she drew of herself in her poems perhaps, or

projected by her anger as she withdrew into her own dark

world, was that of a Salvia (a fragile blue flower with

which she shared her name) which had been “pressed” by the

weight of the Lutheran rule of her father, who had once

begun to train as a Lutheran minister.  Released now from that

oppression, hunched and “secret” in her “hair-tent”, she

became like a witch, or a High Priestess, serving a god of

the Underworld in an hypnotic trance: and from her “Sleep”,

“Darkness”21

began to pour into the world “like perfume”. But this

perfume came from a burst “coffin”, and the light, too, was

like the elusive, delusive, phosphorescent light of methane

corpse-gas. Ted, “blinded” by that darkness, struck a

light: but methane is explosive. After the brief hiatus

(marked by a section break in his poem) he woke

upside-down, totally disorientated and “giddy”, to find

that he, too, was in the “spirit-house”, controlled by

spirits and burning in the flames he had “unwittingly” lit

in Sylvia.

Released now from that

oppression, hunched and “secret” in her “hair-tent”, she

became like a witch, or a High Priestess, serving a god of

the Underworld in an hypnotic trance: and from her “Sleep”,

“Darkness”21

began to pour into the world “like perfume”. But this

perfume came from a burst “coffin”, and the light, too, was

like the elusive, delusive, phosphorescent light of methane

corpse-gas. Ted, “blinded” by that darkness, struck a

light: but methane is explosive. After the brief hiatus

(marked by a section break in his poem) he woke

upside-down, totally disorientated and “giddy”, to find

that he, too, was in the “spirit-house”, controlled by

spirits and burning in the flames he had “unwittingly” lit

in Sylvia.

Like an explosion in an Alchemist’s athanor at this critical stage, this violent explosion may have been the result of impurities in the mixture of Sulphur and Quicksilver, male and female, but Ted puts it’s immediate cause down to his own inattention to the delicate balance of the fires involved. Whatever the cause, the result, for Ted, was disastrous. His own Cabbalistic poetic journey and his life were overturned and suspended, and he returned again to the state of The Hanged Man. In the mythological matrix of Birthday Letters, however, he was not just Odin suspended upside-down on the Tree of Life, he was also, now that Sylvia was completely in the thrall of the dark, Underworld energies of the unconscious, the sacrificed husband or lover of the Goddess – the one who dies (as Dionysus died for Demeter; as Dumuzi died for Innana; as Osiris, Attis, Tamuz and others died) so that fertility might be restored to the world.

Like the religious fanatic with which ‘The God’ began, all Sylvia’s love was unconditionally focussed on the one thing which she believed to be essential to her. And if she did claim, as Ted says in his poem, that God was speaking through her, then Ted certainly would have been horrified. Always superstitious, he would have know that prophets who proclaim their status in that way invariably were burned to death as heretics or witches, or they were consumed by their own inner fires, by fanaticism, martyrdom or madness.

The voice of Ariel was heard in Sylvia’s poetry “for the next five months” (WP 188). It was as if Sylvia suddenly had access to her unconscious world, but it was a dark world of fierce anger and bitterness, full of blackness, atrocities, blood and death. The blood, as Ted made clear in many of the Birthday Letters poems, was her own: but there were “blood gobbets” of him there, too. In a letter which Ted wrote in 1989 to Anne Stevenson22 , he referred to two of Sylvia’s poems, ‘Event’ and ‘Rabbit Catcher’, both of which Sylvia wrote shortly after ‘Elm’, and both of which tell very personal “embryo stories”. The “only thing” Ted had found “hard to understand” at that time, he told Anne Stevenson, was Sylvia’s “sudden discovery of our bad moments” as “subjects for poems”.

And Ted was not the only one Sylvia sacrificed to her ‘God’ in the cause of fertility and creative rebirth. Like one possessed, she offered all who loved her to the flames, used all their lives in her work, and fed the flames until she herself was consumed by them.

So, on this Path, Sylvia experienced all the energies of Hod and Netzach: Splendour, Glory, Victory, Endurance – but all were distorted by their Qlippoth of rigidity, habit, false ideology and Sylvia’s fixed, unbending focus on her goal. So, Sylvia’s victory was hollow – a burned out shell. The Ariel poems, as Ted wrote to Keith Sagar in 1998, were “double-tongued, triumph and doom”23 . The God who “embraced” her was not the gentle God of Love, but that God’s dark twin, the terrible God of Darkness and Grief.

This “God of the euphemism Grief”, ends Ted’s poem, and ends his own Birthday Letters journeys along the Path of the Tower. But for what is “Grief” a “euphemism”? Pain, sorrow, desolation, martyrdom, incubus, hell on earth: these are just a few of the many synonyms offered by Roget’s Thesaurus. But no word can express the true anguish of grief, so all words are merely euphemisms for that all-consuming state which is the darkest expression of love.

And what is the “story” of that God of Grief – the “story which has to be told” – but the story of the Quest, the shamanic journey? That is the story of “the flight to the spirit world” which Ted believed to be “the skeleton of thousands of folktales and myths” (of “Aztec” and “Black Forest” tales, for example, as well as the myths associated with the Mysteries) and of “many narrative poems” (Faas, UU 206). It is the story, too, of Sylvia’s journey to self-healing and self-renewal, especially as Ted tells it in Birthday Letters and, in miniature, in the shamanic ecstasies of ‘The God’. Her “compulsion”, her “desperate” need to “tell everybody” her story was, as Ted said in his interview with Drue Heinz24 , an essential part of the shamanic poet’s journey.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

1. ‘Orghast’, WP 126.

2. In the Bible, the conversion of Saul on the road to Damascus (The Acts (9: 1-9) is an example of the transforming power of Divine revelation. So, too is the conversion of Buddha; and of such hermit saints as St. Francis of Assisi and St. Anthony.

3. Titus Burckhardt, in Alchemy (Element Books, 1987. pp. 161-166) provides an excellent account of the athanor and the three levels of generative fire associated with it.

4. Because the practical Alchemist is working with volatile materials, the danger of an explosion as a chemical reaction takes place is very real. Hendrick Heerschops’ painting, ‘The Alchemist’s Experiment Takes Fire’ shows only a small explosion but some explosions were devastating.

5. For initiates who are immersed in the depths of the unconscious (as they were on the Path of the Devil) and are seeking the enlightenment which is possible on this Path, failure leaves them imprisoned in darkness and, possibly enslaved by the Lord of that darkness.

6. Picasso made many portraits of his close friend Guillaume Apollinaire (1880-1918). They shared an interest in magic, and Apollinaire was also an important avant-garde writer and poet who coined the term ‘Orphism’ for a form of abstract art created entirely from “conceived rather than received reality”. He is, therefore, an appropriate figure to appear in ‘Your Paris’, where Ted’s and Sylvia’s vision of the world is Orphic in just this way.

7. At that time, Sylvia certainly saw her writing, too, in terms of painting and drawing. In a letter written from Paris on 4 July 1956 (SPLH), she likened writing to “a powerful canvas on which other people live and move… ”.

8. At Delphi, the tympanon announced the birth of Iacchos. At Eleusis, an instrument called an echion – “an enormous contrivance with a nerve-shattering effect, which the Greek theatre employed to imitate thunder” announced the birth, amidst fire and smoke, of the holy child Brimos to “the goddess of the underworld”, Persephone. This moment marked the return of Demeter’s daughter from the underworld and the renewal of the fertility of Earth. Kerenyi, Eleusis, Routledge & Kegan Paul, London, 1967. pp. 83-4, 94.

9. “made a note of” is a beautifully ambiguous phrase which suggests both sound and writing. Grammatically, it is part of the sentence about the stolen water bag, but it occurs immediately after a section break which graphically suggests the way in which PAUM! swallows everything which has gone before.

10. Old names for the tarot card of The Tower were ‘The House of the Devil’ and ‘The House of God’. Shiva combines these titles, and the sexual imagery of the Tower is repeated in the Lingam.

11. By my calculation, the Gematria of the word ‘PAUM’ is: 80 + 1 + 6 + 600 = 687. These three numbers (6,7 and 8) are the ruling numbers of this Path. Added together, they reduce to 3, which is the number of the Divine Triangle in which the All Father and the All Mother are joined to the Source. 3 is also the number of the Word, of perfect harmony and of revelation.

12. The daffodil is often called ‘The Herald of Spring’ because of the golden, trumpet shape of its flower, and because it is amongst the first of the Spring flowers to appear.

13. Perhaps the oldest surviving Holy picture of Mother and Child is the Ancient Egyptian papyrus painting of Isis suckling the holy infant Horus. The same grouping of Goddess and holy child was common in votive offerings made at Greek sites associated with the Cult of Persephone. It survives in Christian iconography as images of the Virgin and the infant Jesus, often with a third child present who is identified as the infant John the Baptist.

14. Many practical alchemists recorded the sudden dazzling luminescence which heralded the final stages of the process, although it did not guarantee success in making gold. A well-known painting by Joseph Wright of Derby (d. 1274) illustrates this moment.

15. Jung, Psychology and Alchemy, p. 76, Note 28.

16. St. Thomas Aquinas is reputed to be the author of Aurora consurgens.

17. ‘Elm’ (SPCP 192-3) is dated 19 April 1962. The daffodil photograph which is reproduced in Sylvia’s published journals is dated 22 April 1962. Nowhere in his poem does Ted speak of a photograph, or specify a precise date for his “picture”.

18. St Theresa of Avila (1515-1582) was founder of the Discalced Carmelite order of nuns, an eremitic, ascetic order which followed the Carmelite Rule of prayer, solitude, silence and perpetual abstinence and fasting. In her autobiography, The Way of Perfection, she wrote (and Sylvia copied into her journal) of “devil” inspired hallucinations which filled her with terror; and of the devil being present at her death bed (SPJ Appendix 10. 44 [a-b], 45 [b] - 46 [a]).

19. The Moon Goddess in her light-reflecting form is Selene, Venus, Goddess of Love: the obverse of Hecate, Goddess of the Underworld. Together, these were Sylvia’s “strange muse, bald, white and wild, in her ‘hood of bone’… ” (‘Sylvia Plath: Ariel’, WP 161).

20. Drumming on her thumb with her fingers (checking the rhythms of her lines as she wrote), Sylvia made ‘o’-shaped, moon-shaped circles. The thumb is phallic. In Palmistry, it rises from the Mount of the Moon and belongs to Venus and Hecate; so, it is beloved by witches: “By the pricking of my thumbs / something wicked this way comes”: Macbeth 4 1:46.

21. The position and the capital ‘S’ and ‘D’ of these words gives them emphasis and suggest a reference to Morpheus, son of Hypnos (brother of Death), and the darkness of Hades in which Morpheus dwells.

22. Ted Hughes’s letter to Anne Stevenson, quoted in Malcolm, J. The Silent Woman, PanMacmillan, London, 1994. p. 143.

23. Letter from Ted Hughes to Keith Sagar, 18 June 1998. British Library: DEP 10003 (9).

24. The Paris Review, Vol. 37, No. 134. Spring 1995. pp. 7-8.

Poetry and Magic text and illustrations. © Ann Skea 2003. For permission to quote any part of this document contact Dr Ann Skea at ann@skea.com