MOORTOWN, ELMET AND HEPTONSTALL

“Where is Moortown Farm, and do Elmet and Heptonstall still exist?”

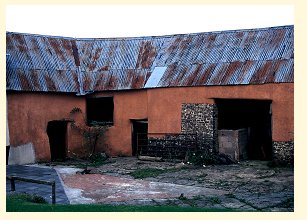

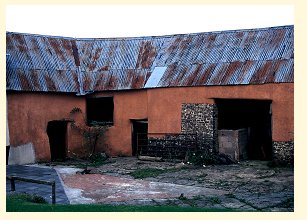

Moortown Farm was owned by Ted Hughes and his wife Carol between 1972 and 1998. The 95 acre farm is about 15 miles from Exeter on the edge of Dartmoor and close to the Devon village of Winkleigh.

Hughes and his wife ran the farm full-time for four years, helping

Carol’s father, Jack Orchard, who is the subject of several of the poems

in the Moortown sequence. After Jack

Orchard’s death the farm was used for agistment (ie other farmers paid to

pasture their stock on the farm). Ted’s letter to Richard Murphy

(LTH 11 March 1976) describes this decision. The Hugheses were

early converts to organic farming.They also planted a range of

old-fashioned species of apple trees on the farm and dug a pond, the site

of which was chosen for them by a water diviner.

Hughes spoke of his farming experiences and read and discussed some of his Moortown poems in a recording he made in 1978 (Link to Transcript). “While I farmed”, he said, “I kept a journal of sorts. Whenever some striking thing happened – and on a stock farm, as in hospital, something is always happening – I made a diary note of it, in a rough sort of verse. My idea was to fix the details, so that I might use them in future, when I had more time to work them into poems or whatever. However, when my farming was over, I looked back and found that some of these entries were already poems of a sort. They were quite unalterable, by me anyway.”

In a letter to his daughter, Frieda, (LTH Late June 1975) Ted described the farming activity which is part of his Moortown poem ‘Last Load’ (THCP 528).

Elmet (which is the setting for the poems in Remains of Elmet (1979) and the later Elmet (1994)) is the old name for the British Celtic Kingdom which once existed around the Calder Valley west of Halifax, in Yorkshire. This area is still a rugged place of moors and crags, and for centuries it was a notorious refuge for criminals and a hideout for refugees. Early subsistence farming took place on hillside terraces but farming here in the Pennines meant (and still means) a constant struggle to survive. Cloth-making from wool of local sheep was an early supplement to poor yields from the land, and the people were hardy, and very independent and self-sufficient. In the 1800s, because of the good water supply for machines and good transport, this area became the cradle of the Industrial Revolution. Woolen mills flourished in the Calder Valley, and Hebden Bridge became a centre for the manufacture of corduroy. By the 1930s, however, industry had moved elsewhere, the mills closed and the towns fell into poverty and disrepair.

Ted’s long letter to Fay Godwin (LTH 31 May 1979) describes his feelings about Remains of Elmet and about their collaboration on this book. Another letter to Stephen Spender (LTH 9 Sept. 1979) also comments on his feelings about the book. Ted gave rather different reasons for the book in a much later letter to Anne-Lorraine Bujon (LTH 16 Dec. 1992).

The background of the poem ‘Football at Slack’ ( THCP 474) is discussed in a letter to Nick Gammage (LTH 29 Nov. 1989), and there are comments about Billy Holt (the subject of the poem ‘For Billy Holt’ (THCP 483)) and his horse, Trigger, in a letter to Keith Sagar (LTH 16 July 1980)

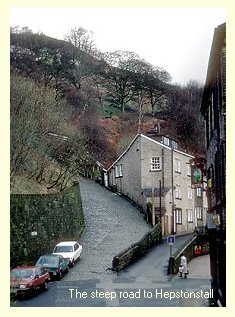

Heptonstall still exists up the old, steep, cobbled street from Hebden Bridge.

Mount Zion, the subject of the poem of that name (THCP 480), has gone, but the other churches pictured in Fay Godwin’s photographs for Remains of Elmet and Elmet, are still there. So, too, are the moors, the ancient trackways, the grouse butts, the standing stones, the skylines, the clouds, the amazing light effects and, of course, the rain.

* * * * * * * *

“In the poem ‘A memory’, who is the person shearing the sheep?”

The poem ‘A memory ’ (THCP 535) is one of six poems at the end of Moortown which were written in memory of Ted’s father–in–law Jack Orchard, to whom the book is dedicated. The other poems in the sequence are ‘The day he died’, ‘A monument’, ‘The formal auctioneer’,‘Now you have to push’ and ‘Hands’.

Jack Orchard farmed Moortown Farm in partnership with Ted and Carol Hughes. In his notes on Moortown Diary in Appendox 1 of Ted Hughes: Collected Poems (pp.1202-1211), Ted writes that Jack had been a retired farmer, one who “belonged to the tradition of farmers who seemed equal to any job, any crisis” and could use anything which came to hand to solve it. His ancestors came from Hartland, opposite the Isle of Lundy which Moorish pirates and their African slaves used to visit, and he spoke “the broadest Devonshire with a very deep African timbre”. “We treat this as a joke” wrote Ted.

* * * * * * * *

“Was Ted thinking of Handel’s Messiah as he wrote ‘The Word that Space Breathes’?”.

It is very likely that Ted was thinking of Handel’s Messiah when he wrote that poem. He certainly knew it and probably knew it very well. You can’t grow up in the North of England without knowing it, there is such a strong choral tradition there and ordinary people are very much involved in that. Handel’s Messiah is also a much loved part of the Easter celebrations in that part of the world.

* * * * * * * *

‘Two’ (THCP 480) and ‘Anthem for Doomed Youth’ (THCP 761). Notes.

Ted was a great collector of folk-tales and myths from around the world. In the opening lines of ‘Two’, Ted adopts and adapts a Blackfoot Indian story in which the Morning Star fell in love with a beautiful woman named Soatsake who was sleeping outside her tipi. He took her to heaven, to the dwelling place of his father and mother, the Sun and the Moon. The Moon gave her a digging stick as a present but forbad her to dig up a turnip in the Spider Man’s garden. Soatsake, consumed by curiosity, pulled up the turnip, but it left a hole in the sky through which she saw the Earth and her people, and she became homesick. As punishment for her disobedience, the Sun sent her back to Earth with her child, where she died. Her son, Poia (Scar-Face), grew up and fell in love with the daughter of a chief, but was rejected, because of the blemish on his face. He determined to seek the help of his grandfather, the Sun, and after a long journey Westwards, fasting and praying, a shining path opened up for him across the sea and he reached the sky. When he came to the Sun’s dwelling place, he found his grandfather being attacked by seven huge, black birds. He rescued his grandfather, who rewarded him by removing his scar, giving him a gift of raven’s feathers (and in some versions a magic flute), and showing him the Wolf’s Path, by which he returned to earth. Poia married the chief’s daughter and took her to live with him in the sky.

In Ted’s version of this story, the two who step down from the Morning Star are not Soatsake and Poia, but two young boys, Ted and his brother Gerald. In a letter which Ted wrote to me in November, 1982 (British Library: Add.74257) he said: “‘Two’ is simply about my brother and myself. He was ten years older than me and made my early life a kind of paradise… [sic] which was ended abruptly by the war. He joined the RAF, and after the war he came to Australia, where he still lives. The closing of Paradise is a big event”.

Ted’s interest in the Blackfoot story of Soatsake and Poia, and in other American Indian stories, like that of Hiawatha, is very apparent in a companion poem to ‘Two’, which is entitled, appropriately, ‘Anthem for Doomed Youth’ (THCP 761). The first four lines of this poem recall the hunters’ paradise of ‘Two’: “He gave us the morning star, / The medicine bag / Swagged with forests and rivers, and the game / Quaking the earth like a drum”. And the poem describes an outing which took place after Ted’s brother returned from war, and when they were both considerably older.

The images in ‘Two’ depict paradise on Earth, a paradise overflowing with light, colour and beauty. And the war which “broke out” and ended this paradisal state for the two brothers was a real war, in which Ted’s older brother was involved. But there are classical mythological allusions in the poem, as well as Blackfoot folk-tale. The world we are shown is a world held in the “cupped hand” of the Dawn Goddess, Eos, and the two figures step into it like the twin star-gods Hesperus and Phosphorus who, in classical mythology, are perpetually at war with each other for the favour of the Moon Goddess.

The heavenly origin of Ted’s two beings is seen in the way “the sun poured from their feet”; and in way that the “streams spoke oracles of abundance” at their coming. But merged with myth, there is a realistic picture of two poachers stepping from the wooded skyline down the dewy dawn-lit hillside, and carrying the “swinging bodies of hares”. This picture is reinforced by the ambiguity as to the ownership of the “scorched talons”, a description which fits the black, leathery, wrinkled feet of real crows, such as those Ted and his brother used to shoot on the moors, with Ted acting “as a retriever” (WP 11).

‘Two’ was the first of Ted’s poems to openly suggest his shamanic identity, but it did so only to describe the failure of his powers when his older brother, his “guide”, left home to join the Royal Air Force. Such was the impact of that separation on Ted that the shamanic “feather fell from his head / The drum stopped in his hand / the song died in his mouth”. There are aspects of that Blackfoot Indian myth about Soatsake and Poia, too, which suited Ted’s shamanic image. He was the poet (the flute player) who, like Poia, was embarked on a healing, shamanic journey; and two of his own totem animals were the raven/crow and the wolf.

* * * * * * * *

Historical background information about John Wesley and the Calder Valley.

Remains of Elmet and Elmet are set in the Calder Valley, which was the old Kindom of Elmet. Poet and novelist, Glyn Hughes, who is not related to Ted Hughes but became a friend of his, has lived in the Calder Valley for many years. He wrote about this area in Millstone Grit: (republished as Glyn Hughes’ Yorkshire (Chatto & Windus, 1985); revised as Millstone Grit: A Pennine Journey (Pan, 1987), and included information about the life of Billy Holt (subject of Ted Hughes’ poem ‘For Billy Holt’ (THCP 483)).

* * * * * * * *

Notes on ‘Churn–Milk Joan’ , and its similarities to a story which is told in Simon Armitage’s March 2020 poem, ‘Lockdown’. Both poems record the use of boundary stones for the exchanges of goods and money made between commmunities isolated by Plague in the 1600s. Hughes recounts (and doubts) local folk–lore which suggests that the Churn–Milk Joan stone on the moors above Mythomroyd in Yorkshire commemorates the death of a local girl taking milk to the stone during a snow storm.* * * * * * * *

© Ann Skea 2020. For permission to quote any part of this document contact Dr Ann Skea at ann@skea.com