Capriccio: The Path of the Sword (4).

‘The Coat’, ‘Smell of Burning’, ‘The Pit and the

Stones’, ‘Shibboleth’, ‘The Roof’, ‘The

Error’.

© Ann Skea

‘The Coat’ (C 11)

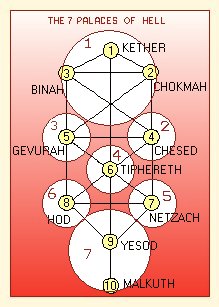

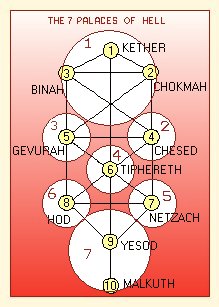

The colon which ends ‘Possession’ (C10) ends the first part of

the sentence imposed by the Goddess on the man and woman of the Capriccio poems.

This first part comprises the first ten poems of Capriccio and these constitute

a complete journey on the Sephirothic Tree in the World of Assiah, which is our

material, everyday world.

After the colon, the second part of the sentence comprises the final ten poems of

Capriccio. These describe a second journey, this time on the Averse Tree which

depends from Malkuth in the Upper World of Assiah into the Infernal Regions of the

Underworld.

So, the colon links the two halves of Capriccio and two complete journeys.

Figuratively, each journey forms a complete circle and these two circles are joined

together, like a Mercurial figure eight, by the colon, which marks the cross-over

between Malkuth at the bottom of the Upper Tree and Kether at the top of the Averse

Tree. Journey is joined to journey just as life is joined to death, light to darkness,

order to chaos, and Heaven to Hell. And, since this continuous and never-ending figure

eight embodies the powers of Mercury, he is thus invoked as guide and psychopomp for

the poet and the reader of this whole Capriccio sequence.

Mercury’s

guiding presence is essential on the Averse Tree of the Underworld, where everything is

reversed. The Sephiroth, there, are areas of dark, unbalanced, raw, Qlippothic

energies. Vices, Illusions and Qlippoth prevail and those who enter this Underworld

enter a place of dis-ease and nightmare. Yet, this is also a place where everything is

broken down into its basic elements so that it may be purified and renewed. Mercury, as

in Alchemy, is essential to this process: so, too, are the Sulphurous fires of Hell.

Ted, in choosing to write the Capriccio poems, chose to enter this place. He

would have been aware of its dangers. Even if we discount any suggestion that he felt

himself to be a skilful enough magician or shaman to attempt this journey, he was aware

enough of the teachings of Jung and Freud to know the psychological perils of

exploring, alone, the deepest parts of his own subconscious. But this is what he did.

Only his mature powers of reason and discrimination could protect him from the

uncontrolled forces of chaos, but by adopting the framework of Cabbala, and by feeling

his way poem by poem along the ordered Paths of the Sephirothic Trees, he gained some

stable form to help him through the darkness.

So, in ‘The Coat’ (C 11), the journey continues; and the

sacrificed human male, who was Setanu in ‘Possession’ (C 10) and who

is also Ted in the Capriccio sequence, enters the Underworld together with the

Goddess’s human priestess, Assia.

‘The Coat’ occupies Kether on the Averse Tree and, together with

‘Smell of Burning’ (C 12) at Chokmah and ‘The Pit and the

Stones’ (C 13) at Binah, it sits in the Triple Hell (or Grave) which

represents the First Palace of Hell in the Infernal Regions. Suitably, then,

corpse-stench, death and horror pervade ‘The Coat’, as does the Qlippoth of

Kether, which is Futility.

In this poem, the Goddess, as in ‘Possession’, exerts her sexual powers,

and her human victims are powerless against her. She remains hidden, like a stalking

tiger, behind the seemingly ordinary trappings of human seduction –

a smoke filled bar, an exotic coat, a haunting perfume. It is “no

help” that these things are “not real tiger” and present

only a shadow of her true nature: the man is mauled just as surely as if he had been

forced through brambles; his limbs are “watermarked”,

“imprinted” with the shocking odour of death, just as surely as if

they had been licked by a hungry tiger. The marmot coat conceals the raw, devouring

energies of lust; the beauty of the tiger’s coat conceals a deadly hunger; and

the Goddess’s powers of enchantment hide her dark, destructive energies.

“Nobody can deter” her. It was “no help” (the

phrase is repeated three times) that her raw energies were concealed beneath a veneer

of civilized behaviour. Such camouflage was “no good”, “it

made no difference”. Her hunger for revenge, as in ‘Possession’,

is “heedless as time”.

The poem begins with the words

“No help”, as if right from the start these humans were the

Goddess’s pawns. And it is quite clear that whatever these two people thought

they were doing, however beautiful their “ferny path” of dalliance,

however pure the “cool, well-ironed sheets” of their bed, whatever

“contract” they carefully made between them, she was behind them all

the time, her “spoor” smudging their most personal and private

moments.

The poem begins with the words

“No help”, as if right from the start these humans were the

Goddess’s pawns. And it is quite clear that whatever these two people thought

they were doing, however beautiful their “ferny path” of dalliance,

however pure the “cool, well-ironed sheets” of their bed, whatever

“contract” they carefully made between them, she was behind them all

the time, her “spoor” smudging their most personal and private

moments.

As Hecate, ‘the old Sow who eats her farrow’, Queen of the Underworld,

the Goddess bewitched her children, then ate them. Here in her Underworld, the couple

lost their identity: their “signature” was smudged, their

“faces” eaten, and they become part of history and myth. The

unleashed powers of Hecate have always brought horror, death and destruction. Here, in

‘The Coat’, Ted likens her vengeance to that of the Old Testament God of

the Hebrews who caused “the bed horror/ Of the Passover night”

1. Her judgment,

like his, is merciless and severe. On the couple in this poem, she unleashed an

uncontrollable, destructive force which raised “Screams that split

bodies” (the phrase suggests dismemberment as well as the forcible parting of

couples), left “the morning empty/ The sun itself silenced”. This

curious last phrase embodies the chaos she caused: the darkness of Hell and the

hollowness of the Qlippothic shells on the Averse Tree are suggested; but the

paronomasia of ‘sun’ and ‘son’ also suggests that the Goddess

had vanquished the male god who had usurped her throne.

Thus, at least temporarily, the old Goddess achieved her ends. But after such

cataclysmic terrors the “face of aftershock” (the anthropomorphism

suggests the human face as well as the (sur)face of the world) is such that

“only dusty stones” – hard, barren, unfeeling,

inhuman rock – “know how to wear” it.

‘Smell of Burning’ (C 12)

‘Smell of Burning’ occupies the Sephira of Chokmah (2) on the Averse

Tree and is thus still in the Grave of the First Palace of Hell. Here, the Qlippoth is

Ambivalence; and the male principal which rules this Sephira is, in this poem, Baal,

The Thunderer, who is known as Tanicus in the German pantheon. His symbol is the

swastika, “the sign of lightning” in the poem, and his element is

Fire.

The woman in this poem, like Assia, is a daughter of this German god and, like her,

Assia may have worn his swastika sign of lightning for protection during her

Jewish/German childhood in Berlin. Hitler was in power at that time and he had adopted

the swastika as a symbol of the Third Reich. Like the woman in the poem, too, Assia, as

a child in a German school, may have been “storm-dancing in other words

marching”.

Ambivalence is everywhere in the double meanings of this poem. The woman is un-named

and, from the very first stanza she is both a child and a “tree in the Black

Forest”. The Black Forest itself is a specific geographical location but also

a dark, underworld forest and its dancing/marching, suggests both the movement of trees

in a storm and the first dark movements of Hitler’s war preparations.

The dancing, the vicarious happiness, the Black Forest Giant, the totem idols and

the proud childish song, all are appearances, sunny fairy-tale images which are

banished by the thunder and burning with which the third stanza begins. Yet, for the

rest of the poem, although ash and cinders and stone and desert surround her, the fire

within this woman continues to burn.

Hints of Assia’s past pervade this poem: the fear and hopelessness of her

Jewish father, the homesickness of her German Protestant mother, and the escape of the

family from Germany to Palestine. But the focus is on the un-named woman,

“you”, whose fear burns so strongly within her that it seems to leak

out of her cigarette and consume her “native resins” so that she

coughs “for oxygen”. The native resins are what she is or was, her

essential self, and the ambivalence within her is that of a displaced person

– one who suppresses her German origins, as her mother does in this

poem, yet burns to return to the place where she belonged and to her childhood

happiness.

As always, the energies of Chokmah, which is Sephira 2, create dualities, but the

final either-or question encapsulates the woman’s dilemma and, if read in

Cabbalistic terms, explains the most fundamental ambivalence of this poem. It suggests,

once more, the identification of Assia with the Goddess/Shekinah. And it asks whether

the ‘you’ of the poem was a female who had been displaced by history, a

native accidentally burned by the fires consuming her native country: or whether she

was “the victim” (the singularity of this phrase suggests her

importance) – the one who was “condemned” by the

unmerciful judgment of a male ‘god’ “to hang” forever on

the burning tree, the essence of which was her own self.

This question is left unanswered and, although Chokmah lies on the Pillar of Mercy,

there is no mercy in the Infernal Regions: so, a disturbing and unbalanced ambivalence

prevails, and the woman continues to burn.

‘The Pit and the Stones’ (C 13)

This poem occupies Sephira 3, Binah, on the Averse Tree. Still in the Grave of the

First Palace of Hell, this Sephira is the last Sephira above the Pit or Abyss which

separates the first three Sephiroth from those of the lower part of the Tree. In the

title of the poem, and in its content, the Pit is clearly present.

The poem is ruled by the Female Principle, the Mother Goddess, whose seat is Binah.

It was her hands which held the man in the poem, and which “led him, tethered

him” and “left him”. In her motherly form, she brought him

forth, nourished him, and tethered him to life, although the Pit was, like death,

always present. “What prompted those hands?”, he asks. He remains

unanswered, unenlightened, but in ‘The Mythographers’ (C 3) at Binah

on the Upper Tree, Ted has already answered that question: he is the Goddess’s

chosen one–the one she marked with her star.

“You”, the woman in ‘The Pit and the Stones’, again

embodies the Goddess as Hecate, Queen of the Underworld. She is seductive, predatory

and dangerous: the Goddess of death and darkness, whose creature is the tigress.

Behind this scenario, too, is the story of Ted, Sylvia and Assia. Ted, tethered in a

troubled marriage to Sylvia, bleating for some release, was found by Assia, whose

attractiveness to men was well known. Her “brimming power” and her

exotic, dangerous beauty seduced him. But what began as an amusement for her became

deadly serious and she fell into the Pit of darkness taking Ted with her.

In ‘The Pit and the Stones’, however, the unnamed man of the poem is

still immersed in an inexplicable chain of events. Ted, too was re-living that

turbulent time as he wrote this poem. Yet, his tone is rational and impersonal, as

befits a Cabbalist who is following the Path of the Sword. He states facts, as he sees

them, as clearly, honestly and unemotionally as possible. But he displays, through the

man’s account of events, the Qlippoth of Binah, which is Fatalism, and he shapes

his poem so that the man and the woman seem to have no choice. His bleats of protest,

the man says, are natural -“a goat merely calls to a goat” and this

is the way it has to be if life is to continue. Only as he looks back does Ted see that

his bleats were, in fact, the loud screams of a creature lusting for another of its own

kind, and that there was a death-note in them which attracted the predatory man-eating

tiger – she of the “many trophies”.

At her coming his reason deserted him. He saw no sense in his tether

– “made nothing” of it except as something which

indicated “his own weakness”: but the ambiguity of this phrase also

suggest that he negated (made nothing) its value in keeping him from the Pit. Darkness,

too, was unreal: “only a sense of darkness”. And voices became just

meaningless noise. In other words, he saw no danger, listened to no advice or warnings,

and ignored restraints.

“So you took him”. This phrase, set in a line by itself, offset

from the margin, mimics the sudden pounce of the tigress; but is states, too, the

man’s helplessness and the fatal inevitability of this seizure. The inevitability

of the outcome, too, is conveyed in the enjambments as the sentence continues into the

next two lines. So, both predator and prey fell into the darkness of the Pit: but only

she was impaled on the deadly spikes. Yet, she was not dead.

The break in the poem between the phrase “you were impaled” and

the next five lines mimics the gulf on the Cabbalistic Tree which this couple had

crossed. And the final five lines of the poem describe the view from the darkness of

the Pit. They end the poem, but there is also a particular Cabbalistic significant to

this number of lines which, here, suggests the total inversion and distortion of every

aspect of the Upper Tree which takes place here in the Infernal Regions.

The symbol of 5 is the

pentagram, the Star of Venus/Astarte, and of Aurora, the Goddess of Dawn. But the

“hatch of dawning sky” which, in ‘The Pit and the

Stones’ is both the mouth of the Pit and the first dawning of sunlight, is

darkened by the watchers who torment the woman as she lies impaled on spikes. The

number 5 is a number of sacrifice, but it is also the number of the Neophyte entering

the Temple of Mysteries before the dawning of new understanding, and, as such, it is

the number of “good in the making” (SSN 35). Here on the

Averse Tree, however, the Temple is the dark Palace of Hell, and the

“jubilation” of the watchers (‘jubilation’ is derived

from ‘Jubilee’, a celebration of a 50 year (5 x 10) anniversary) is

vindictive not joyous, cacophonous and not melodic.

The symbol of 5 is the

pentagram, the Star of Venus/Astarte, and of Aurora, the Goddess of Dawn. But the

“hatch of dawning sky” which, in ‘The Pit and the

Stones’ is both the mouth of the Pit and the first dawning of sunlight, is

darkened by the watchers who torment the woman as she lies impaled on spikes. The

number 5 is a number of sacrifice, but it is also the number of the Neophyte entering

the Temple of Mysteries before the dawning of new understanding, and, as such, it is

the number of “good in the making” (SSN 35). Here on the

Averse Tree, however, the Temple is the dark Palace of Hell, and the

“jubilation” of the watchers (‘jubilation’ is derived

from ‘Jubilee’, a celebration of a 50 year (5 x 10) anniversary) is

vindictive not joyous, cacophonous and not melodic.

The couple understand nothing and the eyes that watch them are

“incomprehensible” to them both. They are tormented by the demons of

Hell, and “Each” and every “stone” of the final

line of the poem is a potential threat. In spite of all this, the dawn is not

completely occluded, so some possibility of a good result remains.

Numerological Note:

This poem is the thirteenth poem of the Capriccio sequence. The first 13

lines also embody the Goddess’s number and describe a fateful, almost mythical

situation. It is a personal story, but it also reflects a common human scenario, as did

those other myth-like historical events mentioned in ‘Capriccios’, the very

first poem of the whole sequence, where the magical power of the number thirteen was

also invoked.

The next eight lines, (8 is Mercury’s number) suggest the tricky, dangerous,

deceptive energies which prevail. But Mercury is only the messenger of the Goddess, the

one who does her bidding according to his own methods, and the phrase, “So you

took him”, begins three lines which, since 3 is her number, convey all her

power.

The final five lines convey naivety and confusion but at their heart is the

“dawning sky” and the possibility of rebirth.

‘Shibboleth’ (C 14)

Below the Grave and the Pit, deeper in the Infernal Regions, lie six more Palaces of

Hell. The next three are situated at Chesed, Gevurah and Tiphereth on the Averse Tree

and they are know respectively as Perdition, The Clay of Death and the Pit of

Destruction.

Always, the energies of Chesed and Gevurah work together and must balance each other

for the true integrity and harmony of Tiphereth to be achieved, but on the Averse Tree

the Qlippoth, Vices and Illusions of these Sephiroth prevent this. So, the mercy of

Chesed becomes sorrow, and the strength of Gevurah becomes cruelty and fear. The

consequent imbalance between Mercy and Justice, which are the Pillars on which these

Sephiroth lie, produces nothing but hollowness and self-sacrifice at Tiphereth, at the

heart of the Tree.

All this is apparent in the poems which occupy these three Sephiroth in this second,

Underworld, cycle of Capriccio. At Chesed (Sephira 4), in the Hell of Perdition,

lies the poem ‘Shibboleth’ (C 14). At Gevurah (Sephira 5), fixed in

the fearful Hell of the Clay of Death, is ‘The Roof’ (C 15). And at

Tiphereth, in the Hell of the Pit of Destruction, is ‘The Error’ (C

16).

In ‘Shibboleth’, in the Hell of Perdition where the energies of

Damnation prevail, everything has to do with judgment and condemnation.

‘Shibboleth’, in the Biblical Old Testament Book of Judges(12: 1-16), is a

word which is used by those in power as a test of tribal origins and allegiances.

Jephthah the Gilead, appointed by the Lord of Israel, decrees that the pronunciation of

the word ‘Shibboleth’ be used by his people to distinguish those of their

own tribe from the people of the tribe of Ephraim, with whom they are at war.

“Four and two thousand” Ephraimites, who could not pronounce the

word ‘Shibboleth correctly, were slain. There is no mercy anywhere in the Book of

Judges for those who do not serve the Lord; and no mercy for the people of those tribes

which challenge the power of his appointed judges.

In Ted’s poem, words and language are, as with the Biblical use of

‘shibboleth’, used as a test of tribal origins. The people who judge

Assia2 are those

“Berkshire County”, upper-class people whose allegiance is to the

English Queen and to the royal House of Windsor, which (like Assia) is of German

origin. Germany had only recently been at war with England, and people with foreign

accents were often regarded with suspicion. Assia, however, had learned to speak with

an upper-class English accent. She may well have learned her English from a mail-order

course purchased by her mother from Fortnum and Mason, an English firm which was

granted its first royal licence as ‘Grocers to the Prince of Wales’ in

18633. In the poem,

however, the “royal licence" is linked to Assia’s German, rather

than to Fortnum and Mason. Nevertheless, the first four lines connect “Your

German”, “royal licence”, “the English”

and “Fortnum and Mason” in such a way that Assia’s origins and

her efforts to fit into English society are introduced as a theme beneath the surface

meaning.

Assia’s Hebrew, which would betray her Jewish blood was hidden, but it

“survived” on the witchy diet of “bats and

spiders” and lay “under [her] tongue” in a way that

suggests that it lurked as a base-note to her English. It lurked, too, in a

“guerrilla priest hole”, so that Assia’s attempts to

infiltrate English society resemble guerrilla warfare, or the clandestine action of an

upholder of a forbidden faith4.

In spite of her efforts, it seems, at some social gathering which turns from dinner

party to hunt-meeting in the course of the poem, Assia’s tongue betrayed her: the

“dizzy silence”, and the flush which darkens her cheeks, mark that

moment of change. Suddenly, the Berkshire County aristocrats become unfriendly,

suspicious, “English hounds”. Their sneers, their

“imperious noses”, their glares, become those of hunting dogs who

have cornered a fox. All of which threw Assia into “panic” so that

her Russian border-country roots surfaced to tangle and trip her (‘tangle’

and ‘trip’ may apply to the tongue and speech as well as to entrapment) and

expose her as a foreigner.

So, she was “pinioned” in “the frontier glare of

customs”, phrases which encompass a forced halt at some border or frontier

between two ethnic groups, the judgment of officials appointed by a governing power,

and, in the word ‘customs’, a reference to socially accepted behaviours

which differ between people of different group.

The final line of this first part of the poem, “Lick of the

tar-brush?”, drawled by the judging “English hounds”, is a

racial insult, as well as the damnation of one who had failed the test which would

allow her to be recognized as one of their own kind. However, beyond its usual

insulting meaning – that the accused has black African blood in

their veins and is therefore not acceptable in white society – there

is an even older meaning which derives from the use of a tar-brush to distinguish the

sheep of one flock from those of another5. It is this

meaning which is most appropriate in this poem, although the racial slur damns the

accusers as well as the accused.

Rejected and surrounded by her accusers, Assia saw, prophetically, her

“lonely Tartar death”. Again, the suggestion of war intrudes into

the poem, along with a reference to Assia’s Russian ancestry. And again, there is

a suggestion that Assia was a brave warrior trying to infiltrate an enemy group.

But the belief of the judges in the supremacy of their own kind, their arrogant

assumption of their right to judge others by their own standards, and their

condemnation of Assia, all demonstrate the demonic inversions which are to be found on

the Averse tree. It is clear that in the Infernal Regions there is no mercy and no love

freely given, only the Qlippoth of Chesed, which is ‘Ideology’, the

Illusion of ‘Being Right’, and the Vice of ‘Tyranny’.

There are other inversions, too. The number of Chesed is 4, the number of the Logos,

the Creative Word: but in ‘Shibboleth’, words, language and pronunciation

are shown to be divisive and destructive. The number 4 also represent “the

Cherubim which guard the Gates of Eden with their swords of fire” (SSN

28): but the guards of ‘Shibboleth’ are snarling dogs and their Eden is

their own worldly domain.

Still, Assia was the worldly representative of the Goddess who fought to regain her

throne and, thus, to mend the divisions caused by severe judgment. Assia’s double

role is suggested by the bats and spiders, creatures of Hecate, which lie under her

tongue; and by her “Black Sea” complexion, which links her with the

dark, salty element of the Goddess and with the thrice-blooming roses (combining the 3

of the Triple Goddess with her flower) which bloom there. In ‘Shibboleth’,

however, the attempts of the Goddess’s chosen woman to infiltrate the ranks of

those closest to the seat of power are a signal failure.

This is made absolutely clear in the final four lines of the poem. The energies of

the number 4, which should have brought change, understanding, and the dawn of

enlightenment, brought to Assia only a vision of herself surrounded and “dumb

like the bound/ Wolf on Tolstoy’s horse”. Significantly, the Wolf in

Tolstoy’s stories is a symbol of untamed, instinctive, energies, and of the cycle

of death, nurture and renewal in Nature. This is the role it plays at the end of

Tolstoy’s story, Kholstomer, (the title is translated as Strider: the

Story of a Horse), in which the horse (itself a creature subjugated by Man) is more

rational than a wolf, and puzzles over Man’s assumption of ownership and rights

over others6. In an explanatory note which Ted wrote about Tolstoy’s image, “the wolf, having willed itself to death (it was alive when they bound it on) is infinetely superior to the men who are standing around staring at it”. Assia, he wrote, “often mentioned it and, I guess identified with it” (LTH p.698). In Ted’s poem, however, Assia feels helpless, rather than superior.

So, in ‘Shibboleth’, the bound Wolf (the word is capitalized at the

beginning of the final line of the poem) represents both Assia and the Goddess in her

manifestation as the Great Mother, Nature. But the Wolf was bound and silenced: the

Goddess’s attempt to use her human representative to help her regain her lost

power, had, at that moment, failed.

‘The Roof’ (C 15)

Where power is misused, where ideology and arrogance reign, and where mercy and love

are absent, as they are in ‘Shibboleth’, there can be no security.

‘The Roof’, at Gevurah on the Averse tree shows the results of such

imbalance.

Fear and insecurity pervade the poem, as does Gevurah’s Vice of Cruelty and

its Illusion of Invincibility. The roof, “any roof”, becomes a

symbol of protection. A roof, like other material things associated with security and

comfort in this poem – the silk-line curtains, the Bach fugues, the

bursting wardrobe and the talismanic fob-watch–can provide a feeling of

invincibility. But the illusory nature of such protection against the horrors outside

is suggested by the dark “folds” of the curtains, the wandering

fugitive nature of the music, the “bursting” wardrobe and

“the chain” which secures the watch which, in itself, represents our

illusory belief that we can trap and control time.

Set against the horrors of this poem – the individual suffering

of the “twenty million” dispossessed and murdered people

– a roof seems little enough to offer all those who are

“out there, under the great rain” (the paronomasia of

‘rain’ and ‘reign’ suggests the plight of the dispossessed and

the power of “their murderers”, and both are encompassed by

“all” in line 7). But the nameless “you” in the

poem feels obliged to provide it.

This person has no power, no strength (which is the energy of Gevurah), and lives

“incognito”, ready at any moment to be “evicted”,

“either” by the murdered or by their murderers. That even the

murdered have such power over this person, suggests the psychological and emotional

disorientation wrought by extreme fear and powerlessness, but their ghostly

invincibility, too, is an illusion which the truly strong, at Gevurah, could

banish.

Gevurah lies on the Pillar of Form, but in the Infernal Regions form and pattern are

absent or distorted. The ‘you’ in the poem lives in a state of uncertainty,

expecting old patterns to repeat themselves, and believing, too, that in some way she

must pay for the horrors perpetrated by and experienced by others. To this end, her

pattern of behaviour is that of self-sacrifice and self-negation: she remains

incognito, “waiting for the knock on the door”. Significantly,

Gevurah (like Chesed) lies at the Door to the Temple of Mysteries, where the awakening

‘I am’ of the Neophyte should occur, but the person in this poem has no

identity, no gender either. We can only guess that it might be

Assia7.

Gevurah is also the place where the Sword of Justice must be wielded against the

evils of the world: passivity, here, is folly. The ‘you’ in ‘The

Roof’ shows courage but not action, and her confusion is such, that she does not

have the strength to claim her own identity, nor does she know who she serves or why.

Her “rent” is conditionally accepted by unknown persecutors, she

puts her faith in a roof and a few material things, and, bogged down in the Clay of

Death in this third Palace of Hell, she suffers and waits.

‘The Error’ (C 16)

At the heart of the Sephirothic Tree, beyond and between the Pillars of Mercy and

Justice and connected to both Chesed and Gevurah, lies Tiphereth. At Tiphereth,

everything which has happened higher up the Tree, and especially at Chesed and Gevurah,

is gathered on the Middle Pillar, where balance and wholeness may be obtained.

Tiphereth is a place of transformation, purification, sacrifice and mystical rebirth; a

place where the inner voice (or the Voice of the Holy Guardian Angel) is heard; a place

where the fierce rays of the Tiphereth Sun either purify or totally consumes those who

are exposed to its fires. The Virtue of Tiphereth is Dedication to the Great Work

– the perfection of the human Soul. Its Vice is Pride, and its

Qlippoth is Hollowness.

‘The Error’ lies at Tiphereth on the Averse Tree in the Fourth Palace of

Hell–the Pit of Destruction. Here every aspect of Tiphereth is present, but in

its most negative form.

As in ‘Shibboleth’ the “you” in ‘The

Error’ is clearly Assia and the historical story of Ted’s, Sylvia’s

and Assia’s linked lives lies behind the anonymity in the poem. Again, on this

Path of the Sword, Ted wields his weapon as dispassionately as possible as he envisions

and tries to understand what happened. He questions and analyses, still within the

framework of Cabbala. And the answers he finds are part of the broader meaning which

Cabbala offers.

Assia knelt, not at an altar but at a grave – Sylvia’s

grave. The ‘Great Work’ to which she dedicated herself was that of

self-incineration “in the shrine” of Sylvia’s death. Her

sacrifice was total: her “whole life” devoured by her

“nun”-like devotion to this unholy cause. And she burned with such

religious fervour, was so self-absorbed, and so convinced that to

“fearlessly”8 incinerate

herself was the right thing to do, that others, even her baby daughter and

(metaphorically) “the German au-pair” were consumed by her

“offered–up flames”.

Why did she do this?. Why did she kneel the edge of Sylvia’s grave

“To be identified / Accused, incriminated”?. Why did she let others

(the stone-holders who threatened her also in ‘The Pit and the Stones’)

dement her? Their stony “proof” of their own

“innocence” accused her and implied that she was guilty, and

Ted’s answer to these questions–that she “mis-heard a

sentence”–uses the ambiguity of ‘sentence’ to suggest that

she accepted that accusation and that her subsequent actions were an atonement. But in

the Infernal Regions everything is distorted. Whatever inner voice of conscience was

guiding her (and at Tiphereth this is the voice of the Holy Guardian Angel), its

sentence was garbled by the threat and accusation of the stone-holders, so that she

misheard , mistranslated, and “mistook” its guidance.

She could, Ted suggests, have used her own magic (hair is traditionally believed to

have strong magical powers) to fly from the grave. Even after that first incendiary

sacrifice (which at Tiphereth would have been a purification), she could have doused

the flames (in “a carpet”), got “to a hospital”,

“Escaped” and called the whole thing “An error in

translation”. Instead, she chose to compound her error by feeding herself to

the tar and brimstone of Hell’s fires.

In the final lines of ‘The Error’, Ted suggests the hollowness of

Assia’s belief that her patient dedication to this self-imposed martyrdom would

achieve something of value. It was, he says, as if she were “feeding a

child”: but there was no child. In the last four lines of the poem Ted wields

his Sword with devastating, unemotional rationality, cutting to the heart of the

matter. “All” Assia was doing, he states, was “being

strong”, “waiting” for the fires to destroy her and for

her “ashes / To be complete and cool”.

Even with the imbalance of Justice and Mercy at Chesed and Gevurah, and the chaos

which consequently ensued, there was a moment of choice at Tiphereth in which things

could have changed. Only Assia could make that choice, and, at the time, Ted could only

“watch”. But Assia’s error combined the Illusion of Tiphereth

(Identification) with its Vice (Pride). She adopted a set of behaviours (a Samurai-like

belief in atonement for guilt by heroic self-sacrifice) which she mistakenly believed

to be right and she did so without questioning her own judgment or considering others.

Because of this error, there was no mystical rebirth, Hollowness prevailed, and no

mystical child was born to fill the empty room of Tiphereth. Exposed to the Sun of

Tiphereth, Assia was destroyed: only the ashes of her Self survived.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

1. On the night of the Passover (as it became known) the Lord slew “all the

first born of the land of Egypt, both man and beast” (Exodus 1:11-12),

sparing only those obedient Jews who had smeared their doorways with the sacrificial

blood of a lamb.

2. The “you” in ‘Shibboleth’ is more clearly associated

with Assia than in some other Capriccio poems, but by the use of this pronoun

Ted not only maintains the rational, impersonal approach suited his work on the Path of

the Sword, he also confirms the loss of individual identity brought about by the

Goddess in ‘The Pit and the Stones’.

3. Fortnum and Mason has held many royal licences, granted not only by English

royalty but also by members of foreign royal families. It has always prided itself on

its ability to ship anything anywhere in the world, but it is best know for supplying

caviar and champagne picnic hampers and other ‘essential’ luxuries to the

elite.

4. Priest-holes were concealed hiding-places for priests constructed in the homes of

English Roman Catholic families so that they might continue to celebrate Mass during

the times when Roman Catholics were persecuted by law.

5. All the sheep in one flock are said to be “tarred with the same

brush”.

6. Perhaps co-incidentally, Kholstomer, too, is a story about the divisions

between different groups of Nature’s creatures and about the misuse of power.

7. The bursting wardrobe, the love of Bach’s music and, especially, the

reference to twenty million murdered people, which suggests the Jewish Holocaust, all

hint that the ‘you’ in the poem is Assia. In the context of Cabbala,

however, these roofless people may well be the exiled Jewish people and the

‘you’ in the poem the exiled daughter of Israel, the Shekinah. Her dwelling

place is that of the Soul of the Jewish people. And the task of the Jewish Cabbalist is

to reunite the Shekinah, who is the female aspect of God, with the male aspect of God

and, thus, to end her, and Israel’s, exile and restore wholeness and harmony.

8. In Ted Hughes: Collected Poems, ‘fearlessly’ has been replaced

by ‘selflessly’, thus reinforcing the folly and error of such thinking.

The poem begins with the words

“No help”, as if right from the start these humans were the

Goddess’s pawns. And it is quite clear that whatever these two people thought

they were doing, however beautiful their “ferny path” of dalliance,

however pure the “cool, well-ironed sheets” of their bed, whatever

“contract” they carefully made between them, she was behind them all

the time, her “spoor” smudging their most personal and private

moments.

The poem begins with the words

“No help”, as if right from the start these humans were the

Goddess’s pawns. And it is quite clear that whatever these two people thought

they were doing, however beautiful their “ferny path” of dalliance,

however pure the “cool, well-ironed sheets” of their bed, whatever

“contract” they carefully made between them, she was behind them all

the time, her “spoor” smudging their most personal and private

moments.

The symbol of 5 is the

pentagram, the Star of Venus/Astarte, and of Aurora, the Goddess of Dawn. But the

“hatch of dawning sky” which, in ‘The Pit and the

Stones’ is both the mouth of the Pit and the first dawning of sunlight, is

darkened by the watchers who torment the woman as she lies impaled on spikes. The

number 5 is a number of sacrifice, but it is also the number of the Neophyte entering

the Temple of Mysteries before the dawning of new understanding, and, as such, it is

the number of “good in the making” (SSN 35). Here on the

Averse Tree, however, the Temple is the dark Palace of Hell, and the

“jubilation” of the watchers (‘jubilation’ is derived

from ‘Jubilee’, a celebration of a 50 year (5 x 10) anniversary) is

vindictive not joyous, cacophonous and not melodic.

The symbol of 5 is the

pentagram, the Star of Venus/Astarte, and of Aurora, the Goddess of Dawn. But the

“hatch of dawning sky” which, in ‘The Pit and the

Stones’ is both the mouth of the Pit and the first dawning of sunlight, is

darkened by the watchers who torment the woman as she lies impaled on spikes. The

number 5 is a number of sacrifice, but it is also the number of the Neophyte entering

the Temple of Mysteries before the dawning of new understanding, and, as such, it is

the number of “good in the making” (SSN 35). Here on the

Averse Tree, however, the Temple is the dark Palace of Hell, and the

“jubilation” of the watchers (‘jubilation’ is derived

from ‘Jubilee’, a celebration of a 50 year (5 x 10) anniversary) is

vindictive not joyous, cacophonous and not melodic.